Id’d Confederate Wood Drum Canteen – Sgt. Joachim Gibson Co. I, 7th Louisiana Infantry (Louisiana Tigers) – KIA on July 2, 1863 at Gettysburg

$5,500

Id’d Confederate Wood Drum Canteen – Sgt. Joachim Gibson Co. I, 7th Louisiana Infantry (Louisiana Tigers) – KIA on July 2, 1863 at Gettysburg – This Confederate cedar wood canteen, probably a product of the Richmond military depot and armory, remains in excellent condition, retaining both of its typical thin iron retention bands; there are three strap brackets made of tin. Threaded through the strap brackets is the original, thin, russet brown leather sling strap that has parallel, impressed, shallow fullers on either side of the entire strap; the strap is in fair condition, although quite dry and a small broken section in one area – someone seemingly glued the broken sections together a long time ago – we have chosen to leave this as is, and we have also chosen not to attempt to put any leather “preservative” on the strap. The canteen retains its original, turned and carved, wood stopper. Significantly, inked on the exterior, finished side of the sling strap, near one end, just before there is a hand cut slot, perhaps for attaching to a button once affixed to the opposite end of the sling, is the following:

“Joachim Gibson Co I”

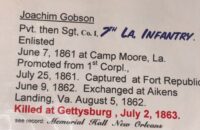

Joachim Gibson, a 28 year old, unmarried laborer, an émigré’ from England living in New Orleans, enlisted in early June 1861, at the rank of Private; quickly promoted to the rank of 1st Corporal, in July 1861, Gibson accompanied his regiment to Virginia, where he was captured during the engagement at Port Republic, on June 9, 1862. After two months in captivity, Gibson was exchanged in early August at Aikens Landing (Aiken’s Landing was located on the north bank of the James River – the Richmond side – just above Varina, and just below the site of where the Dutch Gap Canal was built, in the general vicinity, but up-river, of Deep Bottom. Obstructions had been placed in the James in the neighborhood of Drewry’s Bluff, so Aiken’s Landing was a convenient down-river point at which to transfer Confederate and Federal prisoners.) Gibson was bereft of equipment at the time of his exchange and was probably issued this canteen not long after he rejoined his regiment. At this point in their service, the 7th Louisiana, nicknamed the “Tigers” had shed their original, colorful, elaborate Zouave style uniforms, obtaining more practical uniforms akin to the soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia. ***

Research does not reveal if Gibson immediately rejoined his regiment upon his exchange, but he does reappear on the company rolls in January 1863; during the Fall and early Winter of 1862, the Tigers would participate in the Battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg. In the Spring of 1863, Gibson, along with his regiment, would participate in the Battle of Chancellorsville. According to records at the Confederate Memorial Hall in New Orleans, Gibson was killed in action, on July 2, 1863, during the 7th Louisiana’s assault on Cemetery Hill.

***The Famed Louisiana Tigers at Waynesboro, Pennsylvania

References to the Tigers wearing their Zouave uniforms in Waynesboro by this point ( early 1862) of the Civil War are absolutely incorrect. As the war progressed in 1862, the Bureau of Clothing in Richmond (Richmond Depot) was already consolidating and issuing Richmond patterned clothing to the men of the Army of North Virginia. The commutation system of clothing was already prohibited by this point and the issuances of clothing to the soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia consisted of a Richmond Depot made shell jacket, trousers, headgear and other various clothing and equipment. Although several states that clothed its soldiers such as North Carolina or South Carolina were prominent, there is no evidence suggesting the Tigers were wearing flashy uniforms. This can be attested to by the citizens of Waynesboro itself, in that the residents could not tell the Tigers apart from other units of Early’s Division.

In 1862, most of the Louisiana troops received clothing from the Richmond Depot. The Tigers were among those men to receive clothing. Some of the soldiers decided to consolidate the new look, while keeping portions of their sun bleached uniforms. Taking into consideration the clothing issuances after the Maryland Campaign of 1862, the Tigers lost the Zouave appearance and looked no different than that of the average soldier in the Army of Northern Virginia.

| Comments

(Memorial Hall Records, New Orleans, La.) |

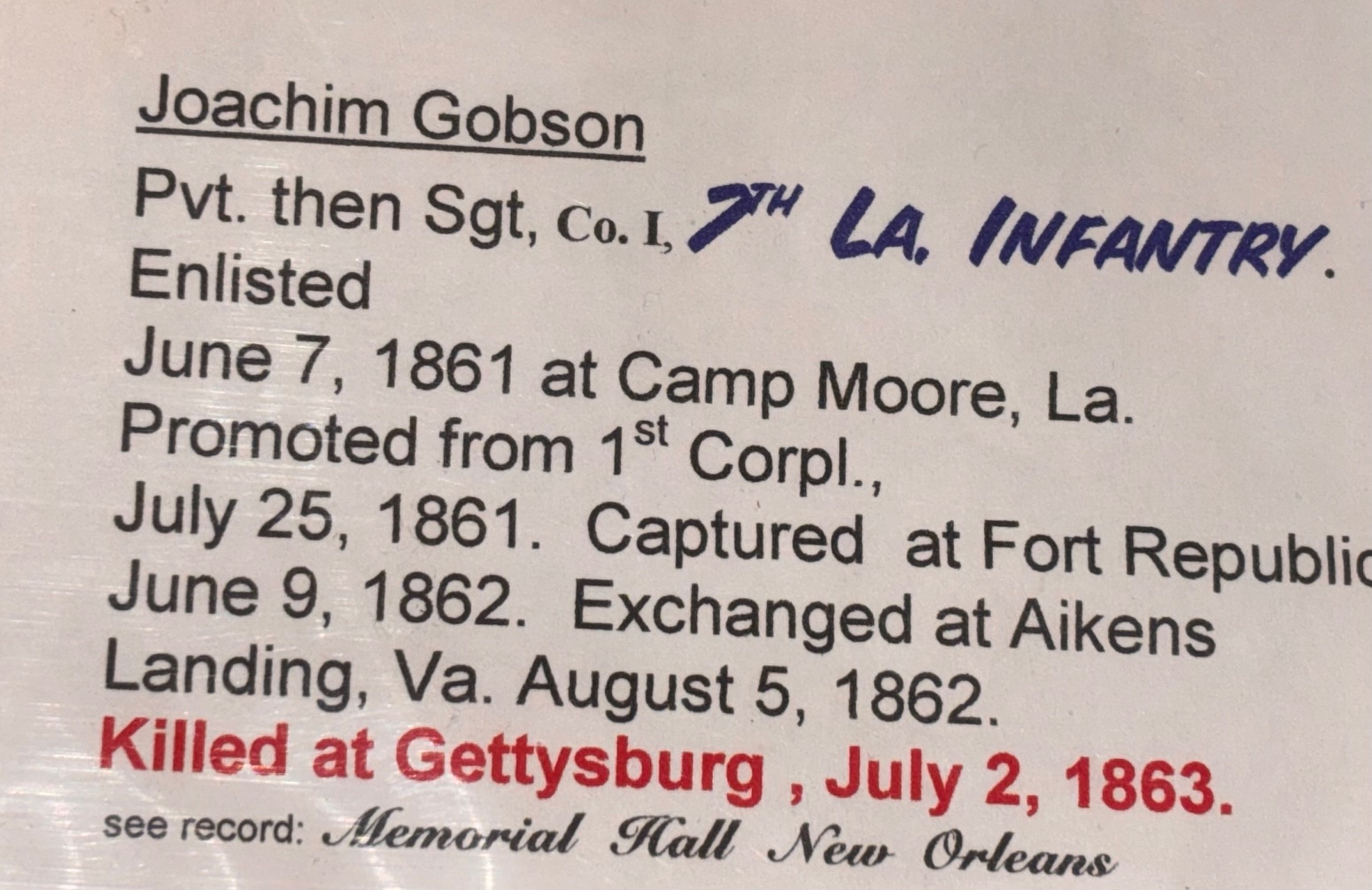

Gibson, Joachim, Pvt. Sergt. Co. I, 7th La. Inf. En.

June 7, 1861, Camp Moore, La. Roll for July and Aug., 1861, Present or absent not stated. Promoted from 1st Corpl., July 25, 1861. Rolls from Sept., 1861, to Feb., 1862, Present. Roll to June 30, 1862, Present, captured Fort Republic, June 9, 1862. Federal Rolls of Prisoners of War, Captured Fort Republic, June 9, 1862. Exchanged at Aikens Landing, Va., Aug. 5, 1862. Rolls from Jan., 1863, to April, 1863, Present. Rolls to Aug., 1863, Killed at battle of Gettysburg, Pa., July 2, 1863. Record copied from Memorial Hall, New Orleans, La., by the War Dept., Washington, D. C., May, 1903, Born England, occupation laborer, res. New Orleans, La., age when enlisted 28, single. Killed at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863. Was captured at Pt. Republic, returned before battle of Richmond. |

| Name | Joachim Gibson |

| Military Year | Abt 1861-1865 |

| Military Place | Abt 1861-1865, Louisiana, USA |

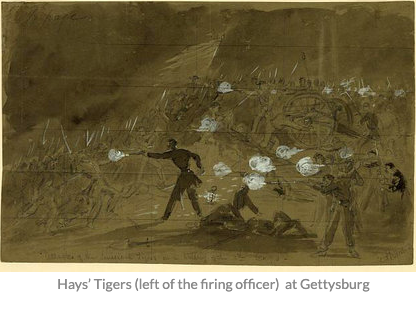

Louisiana soldiers, primarily in Hays’ and Nicholls’ brigades, suffered heavy casualties during the desperate July 2, 1863, assault on East Cemetery Hill, with roughly 724 total casualties reported for Louisiana units throughout the three-day battle. Specific casualties on July 2 included members of the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th Louisiana regiments.

- Key Action: On the evening of July 2, the Louisiana “Tigers” brigade participated in a charge on East Cemetery Hill, resulting in intense close-quarters combat and significant losses.

The 7th Louisiana Infantry, part of Harry T. Hays’ Brigade (part of Ewell’s Corps), fought at Gettysburg on July 1st, helping to rout the Union XI Corps, and notably participated in the fierce, late-evening assault on Cemetery Hill on July 2nd, pushing into Union lines before being repulsed, suffering significant casualties in these actions.

Key Engagements:

- July 1st (First Day): The regiment was involved in the initial fighting, pushing Union forces back through town and onto the hills.

- July 2nd (Second Day): The 7th Louisiana was heavily engaged in the late-day attack on the right flank of the Union line, storming Cemetery Hill and engaging in desperate hand-to-hand combat, achieving a breakthrough but ultimately failing to hold the position due to lack of support.

- Casualties: They suffered substantial losses, with about 24% of their engaged men killed, wounded, or missing, a testament to their intense fighting.

Location:

- They were part of Hays’ Brigade, which, after the initial day’s fighting, was positioned to assault the eastern face of Cemetery Hill.

In essence, the 7th Louisiana was on the front lines of the Confederate assault on the Union’s right flank at Gettysburg, particularly on the evening of July 2nd, near Cemetery Hill.

Battle of East Cemetery Hill

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Confederate | Union | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Richard S. Ewell | Oliver O. Howard | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Louisiana Tigers Brigade | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy | |||||||

The battle of East Cemetery Hill during the American Civil War was a military engagement on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, in which an attack of the Confederacy‘s Louisiana Tigers Brigade and a brigade led by Colonel Robert Hoke was repelled by the forces of Colonel Andrew L. Harris and Colonel Leopold von Gilsa of the XI Corps (Union Army), plus reinforcements. The site is on Cemetery Hill‘s east-northeast slope, east of the summit of the Baltimore Pike.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee assigned Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell‘s Second Corps to launch a demonstration against the Union right to distract the Army of the Potomac during Longstreet’s attack to the south-southwest (Hood’s Assault, McLaws’ Assault, and Anderson’s assault). Ewell was to exploit any success his demonstration might achieve by following up with a full-scale attack at his discretion. Preceded by a 4 p.m. artillery barrage from Benner Hill, the demonstration’s infantry attack commenced with Johnson’s Assault on Culp’s Hill. The Union artillery lunettes on East Cemetery Hill provided protection from the barrage, and the counterbattery fire on Ewell’s 4 batteries forced them to withdraw with heavy casualties (e.g., Major Joseph W. Latimer).

The attack on East Cemetery Hill

Baltimore Pike: Artillery lunettes downhill and along the east of the pike were uphill of the Union infantry line at the Brickyard Lane stone wall.

Northwest: Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes‘s division along the dirt path (now Long Lane) in the darkness was not ready to attack a different side of Cemetery Hill until the east battle was almost over.

Engagement

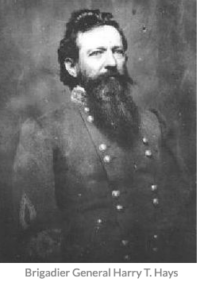

After the Confederates attacked Culp’s Hill at about 7 p.m. and as dusk fell around 7:30 p.m., Ewell sent two brigades from the division of Jubal A. Early against East Cemetery Hill from the east, and he alerted the division of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes to prepare a follow-up assault against Cemetery Hill proper from the northwest. The two brigades from Early’s division were commanded by Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays: his own Louisiana Tigers Brigade and Hoke’s Brigade, the latter commanded by Colonel Isaac E. Avery. They stepped off from a line parallel to Winebrenner’s Run southeast of town. Hays commanded five Louisiana regiments, which together numbered only about 1,200 officers and men. Avery had three North Carolina regiments totaling 900.

The 2 Union brigades of 650 and 500 officers and men. Harris’ brigade was at a low stone wall on the northern end of the hill and wrapped around the base of the hill onto Brickyard Lane (now Wainwright Av). Von Gilsa’s brigade was scattered along the lane as well as on the hill. Two regiments, the 41st New York and the 33rd Massachusetts, were stationed in Culp’s Meadow beyond Brickyard Lane in expectation of an attack by Johnson’s division. More westerly on the hill were the divisions of Maj. Gens. Adolph von Steinwehr and Carl Schurz. Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, nominally of the I Corps, commanded the artillery batteries on the hill and on Steven’s Knoll. The relatively steep slope of East Cemetery Hill made artillery fire difficult to direct against infantry because the gun barrels could not be depressed sufficiently, but they did their best with canister and double canister fire.

Attacking with a Rebel yell against the Ohio regiments and the 17th Connecticut in the center, Hays’ forces bounded over a gap in the Union line at the stone wall. Through other weak spots some Confederates reached the batteries at the top of the hill and others fought in the darkness with the 4 remaining Union regiments on the line at the stone wall. On the crest of the hill against the gunners of Wiedrich’s New York battery and Ricketts’ Pennsylvania battery “with bayonet, clubbed musket, sword, pistol, and rocks from the wall,… 75 North Carolinians of the Sixth Regiment and 12 Louisianian’s of Hays’s brigade… cleared the heights and silenced the guns.”

The 58th and 119th New York regiments of Krzyżanowski‘s brigade reinforced Wiedrich’s battery from West Cemetery Hill, as did a II Corps brigade under Col. Samuel S. Carroll from Cemetery Ridge arriving in the dark double-quick over the hill’s south slope through Evergreen Cemetery as the Confederate attack was starting to ebb. Carroll’s men secured Ricketts’s battery and swept the North Carolinians down the hill to sweep the Louisiana attackers down the hill until they reached the base and “flopped down” for Wiedrich’s guns to fire canister at the retreating Confederates.

Brig. Gen. Dodson Ramseur, the leading brigade commander, saw the futility of a night assault against artillery-backed Union troops in 2 lines behind stone walls. Ewell had ordered Brig. Gen. James H. Lane, in command of Pender’s division, to attack if a “favorable opportunity presented”, but when notified Ewell’s attack was starting and Ewell was requesting cooperation in the unfavorable attack. Losses on both sides were severe; e.g., Confederate Col. Avery: “…tell my father I died with my face to the enemy.

7th Regiment, Louisiana Infantry

Overview:

7th Infantry Regiment [also called the Pelican Regiment] was organized in May, 1861, and entered Confederate service at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in June. The men were from New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Donaldsonville, and Livingstone. Ordered to Virginia with more than 850 men, the unit served under General Early at First Manassas. Later it was brigaded under R. Taylor, Hays, and York. It was prominent in Jackson’s Valley Campaign and on many battlefields of the Army of Northern Virginia. The 7th served from the Seven Days’ Battles to Cold Harbor, then was involved in Early’s operations in the Shenandoah Valley and the Appomattox Campaign. It took 827 men to First Manassas, had 132 disabled at Cross Keys and Port Republic, and lost 68 during the Seven Days’ Battles and 69 in the Maryland Campaign. The unit sustained 80 casualties at Chancellorsville and 24 at Second Winchester, lost twenty-four percent of the 235 engaged at Gettysburg, and had 180 captured at Rappahannock Station. It surrendered with no officers and 42 men. The field officers were Colonels Harry T. Hays and Davidson B. Penn, Lieutenant Colonels Charles DeChoiseul and Thomas M. Terry, and Major J. Moore Wilson.

7th Louisiana Infantry Regiment

The 7th Louisiana Infantry enrolled 1,077 men during the Civil War. Of these, 190 men were killed or died of their wounds, 68 died of disease, 2 were killed in accidents, 1 was murdered and 1 executed. Fifty three were known to have deserted and 57 took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States.

| 1861 | |

| May | Organized at Camp Moore from men from New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Donaldsonville and Livingston. |

| June 5 | Mustered in at Camp Moore with 944 men under the command of Colonel Harry T. Hays, Lieutenant Colonel Charles DeChoiseul and Major Davidson B. PennCompany A – “Continental Guards” – Captain G. Clark Company B – “Baton Rouge Fencibles” – Captain A.S. Herron Company C – “Sarsfield Rangers” – Captain C.M. Wilson Company D – “Virginia Guards” – Captain R.B. Scott Company E – “Crescent Rifles Company C” – Captain S.H. Gilman Company F – “Irish Volunteers” – Captain W.B. Ratliff Company G – “American Rifles, Company A” – Captain W.D. Rickarby Company H – “Crescent Rifles, Company B” – Captain H.T. Jett Company I – “Virginia Blues” – Captain D.A. Wilson Company K – “Livingston Rifles” – Captain T.M. Terry |

| June | Moved to Lynchburg, mustering over 850 men. |

| June 22-23 | Companies A-E under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles DeChoiseul moved from Lynchburg to Maassas Junction on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Assigned to the Brigadier General Jubal Early’s Brigade at Camp Pickens. |

| July 18 |

Blackburn’s FordTwo men were killed and to were wounded. |

| July 21 |

First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run)The regiment was temporarily assigned to Longstreet’s Brigade and was posted on Chinn Ridge. It participated in the pursuit of the Federal army towards Poplar Ford. In the evening it was stationed a mile northwest of the Stone Bridge over Bull Run at the Carter farm, Pitsylvania, soon known as Camp Hays. The regiment lost 3 men killed and 20 or 23 men wounded. |

| July | Assigned to Walker’s Brigade, 1st (Provisional) Corps, Army of the Potomac. Lieutenant Colonel DeChoiseul took temporary command of Wheat’s Special Battalion while Colonel Wheat recovered from his wound at Manassas. |

| July 25 | The regiment was brigaded under Colonel I.G. Seymour, senior colonel of the Brigade, with the 6th, 8th and 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiments and Wheat’s Battalion. |

| September 29-October 1 | Reconnaissance to Great Falls. |

| October 21 | The regiment was brigaded in the Eighth Brigade of the Army of the Potomac under Brigadier General Taylor with the 6th, 8th and 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiments and Wheat’s Battalion as the First Louisiana Brigade and was assigned to Ewell’s Division. |

| 1862 | |

| May |

Shenandoah Valley CampaignAttached to Taylor’s Louisiana Brigade of Ewell’s Division, which joined Jackson’s Army of the Valley in the Shenandoah. |

| May 7 | Somerville Heights (detachment) |

| May 23 |

Battle of Front RoyalThe regiment was in reserve and suffered only two men wounded |

| May 24 | Middletown |

| May 25 |

First Battle of Winchester |

| June 1 | Mount Caramel |

| June 8-9 |

Battles of Cross Keys and Port RepublicThe regiment lost 132 men, nearly 50% of those engaged, charging a battery supported by the 7th Ohio Infantry. Colonel Hays was badly wounded and Lt. Colonel DeChoisul was mortally wounded. |

| June 19 | Lieutenant Colonel DeChoisel died from his Port Republic wound in Richmond. Major Penn was promoted to lieutenant colonel and Captain Thomas M. Terry of Company K was promoted to major. |

| June 25 – July 1 |

Seven Days BattlesThe 7th Louisiana lost 68 men. |

| July 25 | Colonel Hays was promoted to brigadier general and given permanent command of the brigade. Lieutenant Colonel Penn was promoted to colonel and Major Terry was promoted to lieutenant colonel. |

| June 27 |

Battle of Gaines’ Mill |

| July 1 |

Battle of Malvern Hill |

| August 9 |

Battle of Cedar Mountain |

| August 26 | Bristoe Station |

| August 27 | Ketle Run |

| August 28-30 |

Second Battle of Manassas |

| September 1 |

Battle of Chantilly |

| September |

Maryland CampaignThe regiment lost 69 men in the campaign. |

| September 12-15 |

Siege and Capture of Harpers Ferry |

| September 17 |

Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam)Commanded by Colonel Penn, who was wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas M. Terry took over the regiment, which suffered 69 casualties. |

| December 13 |

Battle of FredericksburgThe regiment was in reserve near Hamilton’s Crossing. |

| 1863 | |

| May 1-4 |

Battle of Chancellorsville |

| May 3 |

Marye’s HeightsThe regiment lost 80 men. Colonel Penn and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Terry were captured. |

| June 14-15 |

Second Battle of WinchesterHay’s Brigade circled around the west side of Winchester and assaulted the Star Fort on the northwest side of town. The 6th, 7th and 9th were in the front line with the 5th and 8th in support as the brigade stormed the fort, capturing its artillery and driving off the defenders. The 7th Louisiana lost 24 men. Captain J. Moore Wilson was wounded and Lieutenant Vitrivius P. Terry (brother of Lt. Colonel Terry) was mortally wounded. |

| July 1-3 |

Battle of GettysburgThe regiment was commanded by Colonel David B. Penn and brought 235 men to the field. It lost 13 men killed, 40 wounded and 5 captured, mostly in the assault on Cemetery Hill on the evening of the second day. Lieutenant W.P. Talbot was killed on July 2. From the monument to Hays’s Brigade at Gettysburg: July 1. Advancing at 3 P. M. with Hoke’s Brigade flanked Eleventh Corps aided in taking two guns pursued retreating Union troops into town capturing many and late in evening halting on East High St. July 2. Moved forward early into the low ground here with its right flank resting on Baltimore St. and skirmished all day. Enfiladed by artillery and exposed to musketry fire in front it pushed forward over all obstacles scaled the hill and planted its colors on the lunettes capturing several guns. Assailed by fresh troops and with no supports it was forced to retire but brought off 75 prisoners and 4 stands of colors. July 3. Occupied a position on High St. in town. July 4. At 2 A. M. moved to Seminary Ridge. After midnight began the march to Hagerstown. |

| November 7 |

Battle of Rappahannock StationThe regiment was part of two brigades defending a bridgehead on the north bank of the Rappahannock River that was overrun in a rare night attack. Over 1,600 Confederate prisoners were taken from the eight understrength regiments defending the bridgehead, with only a few men swimming across the river at their backs. Of the 1200 men of Hays’ Louisiana Brigade, 699 were captured, with 180 captured from the 7th Louisiana. Colonel Penn was captured, and Major J. Moore Wilson took command of the regiment. |

| Late November | The Louisiana Brigade was so reduced by casualties that the 5th, 6th, and 7th Louisiana Infantry Regiments were consolidated into a single company. |

| November-December |

Mine Run Campaign |

| 1864 | |

| March | 500 of the 699 men from the brigade captured at Rappahannock Station were exchanged and returned to duty |

| May 5-6 |

Battle of the Wilderness |

| May 8-21 |

Battle of Spotsylvania Court HouseMajor Wilson was taken prisoner |

| June 1-3 |

Battle of Cold Harbor |

| June | Lynchburg Campaign |

| June -October |

Early’s Shenandoah Valley CampaignAssigned to Hays’ Brigade (Colonel William R. Peck commanding) of Brigadier General Zebulon York’s Consolidated Louisiana Brigade in Gordon’s Division of the Army of the Valley |

| July 9 |

Battle of MonocacyCommanded by Lt. Colonel Thomas M. Terry |

| July 24 |

Second Battle of Kernstown |

| August 25 | Shepherdstown |

| September 19 |

Third Battle of Winchester |

| September 21-22 |

Battle of Fisher’s Hill |

| October 19 |

Battle of Cedar Creek |

| October | The ten regiments of the Louisiana brigade were reorganized as a battalion of six companies with less than 500 men, although it would continue to be referred to as a brigade. Colonel Raine Peck (at 6’3″ and 300 pounds known as “Big Peck”) was given command of the brigade. |

| December | The regiment left the Army of the Valley and returned to the Petersburg defences with the remnants of the Second Corps |

| 1865 | |

| January-March |

Siege of Petersburg |

| February 5-7 |

Battle of Hatcher’s Run |

| February 18 | Colonel Peck was promoted to brigadier general and transferred to the Western Theater. Colonel Eugene Waggaman of the 10th Louisiana was given command of the brigade of 400 men |

| March 25 |

Battle of Fort Stedman |

| April 2 |

Final Assault on Petersburg |

| April 6 |

Battle of Sayler’s Creek |

| April 9 |

Appomattox Court HouseThe 7th Louisiana Infantry surrendered 42 enlisted men. There were no officers. The entire brigade only had 373 men. |

7th Regiment, Louisiana Infantry

Overview:

7th Infantry Regiment [also called the Pelican Regiment] was organized in May, 1861, and entered Confederate service at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in June. The men were from New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Donaldsonville, and Livingstone. Ordered to Virginia with more than 850 men, the unit served under General Early at First Manassas. Later it was brigaded under R. Taylor, Hays, and York. It was prominent in Jackson’s Valley Campaign and on many battlefields of the Army of Northern Virginia. The 7th served from the Seven Days’ Battles to Cold Harbor, then was involved in Early’s operations in the Shenandoah Valley and the Appomattox Campaign. It took 827 men to First Manassas, had 132 disabled at Cross Keys and Port Republic, and lost 68 during the Seven Days’ Battles and 69 in the Maryland Campaign. The unit sustained 80 casualties at Chancellorsville and 24 at Second Winchester, lost twenty-four percent of the 235 engaged at Gettysburg, and had 180 captured at Rappahannock Station. It surrendered with no officers and 42 men. The field officers were Colonels Harry T. Hays and Davidson B. Penn, Lieutenant Colonels Charles DeChoiseul and Thomas M. Terry, and Major J. Moore Wilson.

7th Louisiana Infantry Regiment

The 7th Louisiana Infantry enrolled 1,077 men during the Civil War. Of these, 190 men were killed or died of their wounds, 68 died of disease, 2 were killed in accidents, 1 was murdered and 1 executed. Fifty three were known to have deserted and 57 took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States.

Louisiana Tigers

“Louisiana Tigers” was the nickname of several infantry units of the Confederate States Army from Louisiana during the American Civil War. Originally applied to a specific company, the nickname expanded to a battalion, then to a brigade, and eventually to all Louisianan troops in the Army of Northern Virginia. Although the exact composition of the Louisiana Tigers changed as the war progressed, they developed a reputation as brave but undisciplined shock troops.

The original Louisiana Tigers

The origin of the term came from the “Tiger Rifles,” a volunteer company raised in the New Orleans area as part of Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat‘s 1st Special Battalion, Louisiana Volunteer Infantry (2nd Louisiana Battalion). A large number of the men were foreign-born, particularly Irish Americans, many from the city’s wharves and docks. Many men had previous military experience in local militia units or as filibusters. They (and the regiments that later became known as the Tigers) were organized and trained at Camp Moore.

Origins

The famous filibuster Roberdeau Wheat, returning from Italy in the spring of 1861, intended to raise a company of New Orleans troops and then a full regiment for Confederate service. On April 18, 1861, just a few days after Fort Sumter was attacked by Confederate forces, the New Orleans Daily Crescent carried the following announcement: “We understand that our friend, Gen. C.R. Wheat, is about to raise a company of volunteers, to serve in the Army of Louisiana. His headquarters are on 64 [Saint] Charles [Street], where we advise all friends of a glorious cause to repair and enlist.”

Wheat called his company the “Old Dominion Guards” to commemorate his native state’s (Virginia) recent secession from the United States to join the Southern Confederacy. With the help of Obedia Plummer Miller, a well-established New Orleans attorney, Wheat quickly recruited fifty or so men to his company, mostly expatriate Virginians, men like Henry S. Carey, a relative of Thomas Jefferson’s, Richard Dickinson, who would become Wheat’s adjutant, and Bruce Putnam, a towering man who became Wheat’s intimidating sergeant major.

While Miller, Carey, Dickinson, and Putnam continued recruiting for the Guards, Wheat was able to attract four already-forming companies to his banner: Captain Robert Harris’s Walker Guards, Captain Alexander White’s Tiger Rifles, Captain Henry Gardner’s Delta Rangers, and Captain Harry Chaffin’s Rough and Ready Rangers (later called Wheat’s Life Guards), which were assembling a few blocks away at Camp Davis on the grounds of the “Old Marine Hospital/ Insane Asylum/Iron Works” between Common and Gravier Streets at South Broad (today’s Camp) Street. Many of the men of these precocious units, unlike those from the more upscale Old Dominion Guards, were former filibusters who had served with Wheat or Walker in Nicaragua. Since the late campaigns, they had slipped back into their old jobs as ship hands, stokers, dock workers, watermen, draymen, screw men, stevedores, or simple laborers on the New Orleans waterfront. As such, they were considered as being the lowest members of white Southern society. One disgusted observer proclaimed that many of Wheat’s recruits were “the lowest scum of the lower Mississippi…adventurous wharf rats, thieves, and outcasts…and bad characters generally.”

The Walker Guards were raised under the auspices of Robert Harris, one of Wheat’s former comrades in the Filibuster Wars. As the name denotes, many of Harris’s recruits had “smelt powder…saw the elephant…[and] felt bullets” in Nicaragua. Since the late war, Harris reportedly became the operator of a bawdy gambling establishment along the waterfront. The Tiger Rifles, the Delta Rangers, and the Rough and Ready Rangers, however, Wheat’s other cohorts, made no special claim to fame. All that is known about them, other than the fact that they were largely Irish ship hands, dock workers, stevedores, or draymen, is that the commander of the Rangers, Henry Gardner, had signed a petition which called on the governor of Louisiana to convene a secession convention and declared that the intrepid commander of the Tiger Rifles, Alexander White, was a known felon and river pilot. Similar to William Walker in stature, the fiery “White,” if that was his real name, was reportedly “the son of a one-time Southern governor,” supposedly from Kentucky. During a game of high-stakes poker in his youth, White claimed that he had shot a man who accused him of cheating. Through the influence of his supposed family, he was able to escape prosecution as long as he left the state and went underground. Fleeing to New Orleans, the vast Southern metropolis where it was easy to get lost, White most probably gambled, conned, and boozed his way through life until the War with Mexico when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy to pilot men and material down to Corpus Christi, Tampico, or Vera Cruz. After his five-year enlistment was up, he settled down, got married, and became the captain of the steamer Magnolia, which hauled goods between New Orleans and Vicksburg. During this time White once again lost his temper, severely pistol-whipped a passenger on his steamer, was arrested and convicted, and as a result, ended up in the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Baton Rouge. By March 1861, with Louisiana’s secession and the subsequent U.S. blockade, White began to form a company of volunteers around his crew and was even able to rent prime space for a recruiting station at 29 Front Levee, between Gravier and Poydras streets, near the Custom House and Camp Davis.

Wheat, using his gentlemanly appeal, was apparently able to talk Harris, White, Gardner, and Chaffin into forming a battalion under his command with the assurance that all involved would better be able to control their destinies if they acted as one. And with Wheat’s eminent stature as a Mexican War veteran, a Southern partisan, a former assemblyman, and a general officer in two foreign armies, they would no doubt get the choice assignments and equipment. As such, on April 23, 1861, the New Orleans Daily Crescent carried the following announcement: “Gen. C.R. Wheat, with reference to raising a battalion, invites such of our friends and citizens generally, as feel an interest in the cause, to call at No. 29 Front Levee Street, where they will find the material for the first battalion of the States, and one that will make its mark when called upon.”

With the deal cut, all commands, including the Old Dominion Guards (which was originally assembled across from the prestigious St. Charles Hotel), moved their constituent recruiting stations to Captain White’s on Front Levee Street and recruitment became a shared task. To attract even more bellicose souls to his nascent battalion, men who “were actuated more by a spirit of adventure and love of plunder than by love of country,” or who filibuster General Henningsen once proclaimed “thought little of charging a battery, pistol in hand,” Wheat christened his command “the Tiger Battalion.” He then extolled his volunteers, led by Captain White’s large company of Tiger Rifles who had “painted a motto or picture of some sort on [their]…broad brimmed…hat[s] such as: A picture of Mose, preparing to let fly with his left hand and fend with his right, and the words, ‘Before I Was a Tiger,'” to continue to comb the docks, thoroughfares, alleyways, hotels, poor houses, and jails of the New Orleans waterfront for more recruits. Other slogans that the Tiger Rifles painted on their hats included: “Tiger Bound for Happy Land,” “Tiger Will Never Surrender,” “A Tiger Forever,” “Tiger in Search of a Black Republican,” or “Lincoln’s Life or a Tiger’s Death.”

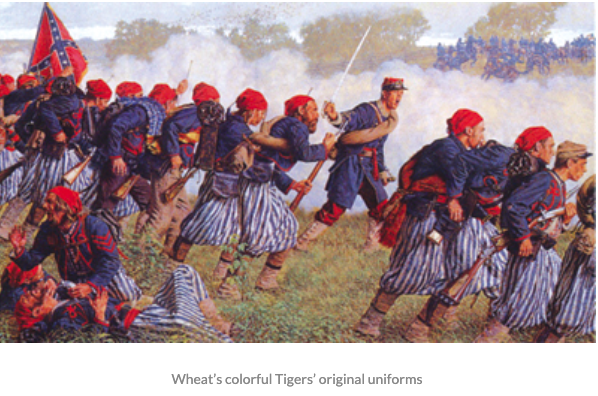

Uniforms and equipment

While the men of the ad hoc battalion continued to attract more recruits—and in some instances impressing “known Yankees” into service, shaving their heads—Wheat worked through the Ladies Volunteer Aid Association of New Orleans to help uniform the Walker Guards, the Delta Rangers, and the Old Dominion Guards in red flannel “battle” or “Garibaldi” shirts and jean-wool trousers “of the mixed color known as pepper and salt.” For headgear, the men apparently retained their own broad brimmed hats of various earthy tones (except Henry Gardner’s Delta Rangers who were reportedly presented with gray or blue wool kepis and white cotton havelocks). Harry Chaffin’s Rough and Ready Rangers were reportedly uniformed in light gray wool jackets and trousers with matching kepis.

The Tiger Rifles received their uniforms from A. Keene Richards, a wealthy New Orleans businessman. Because he was “so impressed by their drill and appearance” at Camp Davis, Richards elected to outfit White’s company as Zouaves: dark blue wool Zouave jackets with red cotton trim (no sereoul), distinctive red fezzes with red tassels, red flannel band collar shirts with five white porcelain buttons, and outlandish “Wedgwood blue and cream” one-and-one-half-inch vertically striped cottonade ship pantaloons that would become their signature. They were also provided with blue and white horizontally striped stockings and white canvas leggings.

Most of the lieutenants and captains of the battalion more than likely uniformed themselves in dark blue wool single breasted frock coats or short jackets with matching trousers, red or blue wool kepis with stiff black leather bills, red officers’ sashes, and white canvas leggings worn over or under the trousers. The officers of the Tiger Rifles most probably wore blue wool single-breasted short jackets with red or blue wool trousers, white canvas leggings, and red wool kepis. Wheat chose to wear the uniform of a field grade officer in the Louisiana Volunteer Militia: a red kepi bedecked with appropriate Austrian gold lace, a double-breasted dark blue wool frock coat with brass shoulder scales, and red wool trousers. He also sported a buff general’s sash, no doubt to commemorate his past commissions in the Mexican and Italian armies.

While Wheat, Richards, and the ladies were gathering the uniforms, the company commanders arranged to have guidons, banners, or full-blown battle flags made for their units. The Walker Guards’ banner was made of “blue silk with a white crescent in the center.” The Tiger Rifles’ flag consisted of a “gamboling lamb” device with “Gentle As” written derisively above it. The Delta Rangers’ flag, which became the battalion’s color at the battle of Manassas by “the luck of the draw,” was a rectangular silk “Stars and Bars” with eight celestial points in a circular pattern. As the five companies were being filled and uniformed, Wheat moved his volunteers to Camp Walker at the Metaire (pronounced met-are-E) Race Course/Fairgrounds in the center of the city near Carondolet Canal and Bayou John. On May 10, 1861, Wheat was elected major by his fellow company commanders (Obedia Miller becoming captain of the Old Dominion Guards) and state officials officially recognized his battalion. On May 14 the battalion was moved eighty miles north by rail to Camp Moore in Saint Helena Parish, near the town of Tangipahoa and the Mississippi border. The encampment, named after Louisiana’s secessionist governor Thomas Overton Moore, was the central depot for organizing, training, and mustering Louisiana volunteer units for Confederate service.

Upon arrival, the Tigers were issued newly fabricated Louisiana Pelican Plate or fork-tongue belts, cartridge boxes, cap boxes, and knapsacks which were manufactured by the New Orleans–based Magee and Kneass or James Cosgrove Leather Companies. They were also issued their weapons. While the Walker Guards, the Delta Rangers, the Old Dominion Guards, and the Rough and Ready Rangers seem to have been issued either M1842 muskets or aged M1816 conversion muskets with socket bayonets, the men of the Tiger Rifles, Wheat’s chosen skirmishers, were issued the coveted M1841 “Mississippi” Rifle, made by the Robbins and Lawrence Gun Company of Connecticut. Governor Moore’s insurgents had seized these accurate weapons, among the best in service at the time, from the Federal Arsenal at Baton Rouge in January 1861. To offset their absence of bayonets, the Tigers were either issued or brought along their own Bowie-style knife or ship cutlasses, implements which were described as “murderous-looking…with heavy blades…twenty inches long with double edged points…and solid long handles.”

Training

With their weapons and equipment in hand, the men of Wheat’s Battalion were trained in the latest light and heavy infantry techniques by the Old Filibuster himself in the pine stands which surrounded Camp Moore. Once their exhausting and sometimes frustrating sessions were over, many of the Tigers often drank, played cards, and got into fights with themselves or other units. One man scoffed that the Tigers were “the worst men I ever saw…. I understand that they are mostly wharf rats from New Orleans, and Major Wheat is the only man who can do anything with them. They were constantly fighting with each other. They were always ready to fight, and it made little difference to them who they fought.” Private William Trahern of the up-country Tensas Rifles (soon-to-be Company D, 6th Louisiana) claimed that he once heard Wheat declare: “If you don’t get to your places, and behave as soldiers should, I will cut your hands off with this sword!” One man was in fact so afraid of Wheat’s belligerent filibusters that he stayed as far away from their encampment as possible. He later wrote: “I got my first glimpse at Wheat’s battalion from New Orleans. They were all Irish and were dressed in Zouave dress [sic.], and were familiarly known as ‘Tigers,’ and tigers they were too in human form. I was actually afraid of them, afraid I would meet them somewhere in camp and that they would do to me like they did to Tom Lane of my company—knock me down and stamp me half to death.”

As the Tiger Battalion meshed at Camp Moore, five other men with less military experience than Wheat were commissioned colonels and their assembled companies were mobilized into regiments for Confederate service. No doubt embarrassed and frustrated, Wheat was spurred to desperate action. On June 6, 1861, he made a creative deal with the state to officially commission him a major of volunteers and to recognize his five companies temporarily as the “1st Special Battalion, Louisiana Volunteers.” With the special or temporary status secured, Wheat hoped to attract four or five more companies and become the colonel of the soon-to-be organized 8th Louisiana Regiment.

In the political wrangling that followed, Wheat’s rowdy dock workers seem to have repelled potential allies to their cause as Henry Kelly, a retired U.S. Army officer from northern Louisiana, became the commander of the Eighth Regiment. With Kelly’s ascension, on or about June 8, Captain Jonathan W. Buhoup’s company of Catahoula Guerrillas voted to leave Kelly’s command and threw in its lot with the Tiger Battalion. As the Guerrillas were primarily the sons of native-born planters or were doctors, lawyers, farmers, overseers, or artisans from Catahoula Parish in northern Louisiana, they were complete social opposites from the majority of the members of Wheat’s Battalion. Originally intending to become part of a cavalry regiment, the Guerrillas outfitted themselves in gray wool short jackets, matching mounted trousers, gray wool kepis, riding boots, and, like the Tiger Rifles, were armed with stout Mississippi Rifles, looking much like dismounted dragoons. Buhoup had lobbied hard for John R. Liddell, a prominent Catahoula Parish planter, to be colonel of the 8th Regiment with himself as its lieutenant colonel. When he and Liddell failed in their bids to gain field commissions, however, Buhoup used what was left of his political leverage to have his company transferred to the Special Battalion where he hoped to gain a field commission once it was converted into a full regiment.

With six companies now under his belt—an interesting cross-section of Louisiana society—one which David French Boyd of the soon-to-be organized 9th Louisiana perceptively described as being “a unique body, representing every grade of society and every kind of man, from the princely gentleman who commanded them down to the thief and cutthroat released from parish prison on condition he would join Wheat….Such a motley herd of humanity was probably never got together before, and may never be again,” Wheat resolved to get his menagerie to Virginia, the seat of war, as soon as possible. Six other Louisiana infantry formations, the First, Second, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Regiments, had already been dispatched from the Pelican State to the Old Dominion and Wheat did not want to miss the grand battle that was supposed to win Southern independence in one fell swoop.

On June 13, 1861, not a week after his battalion’s formal organization, Wheat loaded five of his six companies (the Rough and Ready Rangers were retained at Camp Moore because it failed to sufficiently fill his ranks) aboard a freight train that was bound for Manassas Junction, a major staging area for the gathering Confederate army in Virginia. In so doing, Wheat gave up his bid to form a regiment from the special battalion, at least for the time being, and his unit was officially named the “2nd Battalion, Louisiana Volunteers” by the state. To the officers and men of the battalion, however, they would always be known as the “1st Louisiana Special Battalion,” “the Special Battalion,” “Wheat’s Battalion,” “the Tiger Battalion,” “the Star Battalion,” “Wheat’s Louisiana Battalion,” “the New Orleans Battalion,” or simply as “Wheat’s Tigers.”

The First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas)

The battalion first saw combat during the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), where it anchored the left flank on Matthews Hill long enough for reinforcements to arrive. During this action, the Tiger Battalion conducted several brazen attacks, with Roberdeau Wheat himself suffering a serious wound at the foot of Matthews’s Hill. The Tigers were assigned to Brig. Gen. Nathan George Evans‘s 7th Brigade, Confederate Army of the Potomac, and fought at Stone Bridge, Pittsylvania, Matthews’s Hill, and Henry Hill. All told, the Louisiana Tiger Battalion listed 47 casualties at the battle (31 wounded, 12 killed, 3 captured, and one wounded and captured).

“Report of Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, First Special Battalion Louisiana Volunteers, of the Battle of Manassas, Virginia, July 21, 1861. Manassas, August 1, 1861,

Sir:

I beg leave herewith, respectfully, to report the part taken by the First Special Battalion of Louisiana Volunteers, which I had the honor to command in the battle of July 21. According to your [i.e., Colonel Nathan Evans’s] instructions, I formed my command to the left of the Stone Bridge, being thus at the extreme left of our lines. Your order to deploy skirmishers was immediately obeyed by sending forward Company B under Captain White. The enemy threatening to flank us, I caused Captain Buhoup to deploy his Company D as skirmishers in that direction.

At this conjuncture, I sent back, as you ordered, the two pieces of artillery which you had attached to my command, still having Captain Alexander’s troop of cavalry with me. Shortly after, under your orders, I deployed my whole command to the left, which movement, of course, placed me on the right of the line of battle. Having reached this position, I moved by the left flank to an open field, a wood being on my left. From this covert, to my utter surprise, I received a volley of musketry which unfortunately came from our own troops, mistaking us for the enemy, killing three and wounding several of my men [sic.]. Apprehending instantly the real cause of the accident, I called out to my own men not to return the fire. Those near enough to hear, obeyed; the more distant, did not. Almost at the same moment, the enemy in front opened upon us with musketry, grape, canister, round shot and shells. I immediately charged upon the enemy and drove him from his position. As he rallied again in a few minutes, I charged him a second and a third time successfully.

Finding myself now in the face of a very large force—some 10,000 or 12,000 in number—I dispatched Major Atkins to you for more reinforcements and gave the order to move by the left flank to the cover of the hill; a part of my command, mistake, crossed the open field and suffered severely from the fire of the enemy. Advancing from the wood with a portion of my command, I reached some haystacks under cover of which I was enabled to damage the enemy very much. While in the act of bringing up the rest of my command to this position, I was put hors de combat by a Minie ball passing through my body and inflicting what was at first thought to be a mortal wound and from which I am only now sufficiently recovered to dictate this report. By the judicious management of Captain Buhoup I was borne from the field under the persistent fire of the foe, who seemed very unwilling to spare the wounded. Being left without a field officer, the companies rallied under their respective captains and, as you are aware, bore themselves gallantly throughout the day in the face of an enemy far outnumbering us.

Where all behaved so well, I forbear to make invidious [i.e., unfair] distinctions, and contenting myself with commanding my entire command to your favorable consideration, I beg leave to name particularly Major Atkins, a distinguished Irish soldier, who as a volunteer Adjutant, not only rendered me valuable assistance but with a small detachment captured three pieces of artillery and took three officers prisoners. Mr. Early, now Captain Early, as a volunteer adjutant, bore himself bravely and did good service. My adjutant, Lieutenant Dickinson was wounded while gallantly carrying my orders through a heavy fire of musketry. Captain Miller of Company E, and Lieutenants Adrian and Carey were wounded while leading their men into the thickest of the fight. All of which is respectfully submitted C. R. WHEAT, Major, First Special Battalion, Louisiana Volunteers.”

Tiger execution

After First Battle of Bull Run, the Tigers grew in disrepute in the army due to their rowdy, sometimes uncontrollable behavior, especially after they were assigned to Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor‘s newly-formed “Louisiana Brigade” (later called the 1st Louisiana Brigade” or the “Louisianan Tiger Brigade”), Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell‘s Division, which was encamped (“Camp Florida”) around Centreville, Virginia. After one too many drunken brawls and acts of insubordination, two Zouaves, Dennis Corcoran and Michael O’Brien, from the Tiger Rifles were tried by court-martial on Taylor’s orders and executed. Their remains are interred at the Centreville (Virginia) Church.

Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign

In early spring 1862, Richard Ewell‘s Division (which included Taylor’s Tiger Brigade) was detached from the Confederate Army of the Potomac and sent west to reinforce the Confederate Army of the Valley, which was commanded by Stonewall Jackson. As such, the Tigers participated in his 1862 Valley Campaign, proving instrumental in Confederate victories at the battles of Front Royal, Winchester, and Port Republic. Because of a nasty friendly-fire incident during (and after) the battle of Manassas, the Zouaves of the Tiger Rifles (Company B) decided to dye out the blue in their jackets before the Valley Campaign, making them a ruddy-grey-brown. As for the rest of the battalion, which now consisted of the Walker Guards (A), the Delta Rangers (C), the Old Dominion Guards (D), and Wheat’s Life Guards (E, formerly the Rough and Ready Rangers)(out of disgust, the Catahoula Guerrillas asked for and received a transfer to Maj. Henri St. Paul’s 7th Louisiana Battalion and then the 15th Louisiana Infantry Regiment), they wore the uniform that was issued to them by their state government in the autumn of 1861: two shirts, one checked and one flannel; one bluish-gray jean-wool short jacket with nine Louisiana State buttons and epaulettes, trimmed with black cotton tape; matching trousers; white canvas leggings (buttoned); blue-gray jean-wool kepis with stiff black bills and trimmed with black wool and one variously colored jean-wool over coat. Many of the men apparently chose to continue to wear their distinctive red flannel Garibaldi shirts however, and they probably kept their issue jackets in a bedroll or pack until discarded. Like in 1861, they were armed with either M1842s or M1816 conversion muskets with socket bayonets. “Wheat’s Tigers” were best known for leading the attack, crossing a burning bridge under fire, and seizing a Federal supply train at Front Royal and taking entrenched Federal batteries at the Winchester, and Port Republic.

Seven Days Battles

In late spring, Jackson’s force was sent eastward to participate in the Peninsula campaign. Following Wheat’s death at the Battle of Gaines’s Mill and with but some 60 officers or men under Captain Harris, the Tiger Battalion was merged with the 1st Louisiana Zouave Battalion.

The combined unit took heavy casualties during the Northern Virginia campaign and the subsequent Maryland campaign, where its leader, Lieutenant Colonel Georges De Coppens, was killed. The depleted battalion was transferred from the Army of Northern Virginia after the Battle of Fredericksburg. It served in various districts until it was finally disbanded in December 1864.

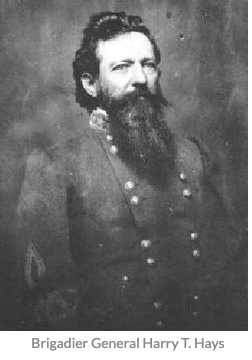

Hays’s “Louisiana Tiger” Brigade

By then, the nickname “Louisiana Tigers” had expanded to encompass the entire brigade, which was commanded by Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays following Taylor’s promotion and transfer to the Western Theater. By the Battle of Fredericksburg in late 1862, Hays’s Brigade was composed of the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiments, and was a part of the division of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early.

One of the Tigers’ greatest moments occurred on August 30, 1862, the third day of the Battle of Second Bull Run, when members of the 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment beat back repeated Union assaults on the Confederate lines, described as follows: “After successfully breaking up three Union assaults, the Tigers found themselves dangerously short of ammunition. Two men of the 9th Louisiana were dispatched to the rear for more but a fourth Union attack was mounted before they returned. The ensuing clash was ‘the ugliyst fight of any” claimed Sergeant Stephens. Groping frantically for ammunition among the dead and wounded, the Louisianians were barely able to beat off the determined Yankees, who threw themselves up to the very muzzles of the Tigers’ muskets. When the Tigers fired their last round, the flags of the opposing regiments were almost flapping together. In desperation Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Nolan shouted for the men to make use of the numerous rocks that lay scattered around the embankment. Sensing that the rebels were at the end of their rope, the Yankees were charging up to the base of the embankment when suddenly fist and melon size stones arched out of the smoke that hung over the grade and rained down upon them. “Such a flying of rocks never was seen,” claimed one witness, as the Tigers and other nearby Confederates heaved the heavy stones at the surprised federals. Numerous Yankees on the front line were killed by the flying rocks, and many others were badly bruised.” — From “Lee’s Tigers: The Louisiana Infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia” (Louisiana State University Press) by Terry Jones.

Another point of pride for the Tigers came at the Battle of Chantilly, September 1, 1862, where a soldier from Company D of the 9th Louisiana was credited with killing Union General Philip Kearny.

During the 1863 Gettysburg campaign, Hays’s Brigade played a crucial role in the Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Winchester, seizing a key fort and forcing the withdrawal of Union troops under Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy. During the subsequent invasion of southern Pennsylvania, much of the populace feared the thievery and drunkenness often associated with the colorful Louisianans. At the Battle of Gettysburg, Hays’s Brigade stormed East Cemetery Hill on the second day and seized several Union artillery pieces before withdrawing when supporting units were not advanced.

In the autumn of 1863, more than half the brigade was captured at the Battle of Rappahannock Station, and 1,600 men were shipped to Northern prisoner-of-war camps, many to Fort Delaware. Most would be paroled and would later rejoin the Tigers. The replenished brigade fought in the Overland Campaign at the Battle of the Wilderness and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, where General Hays was severely wounded.

Final organization

During the subsequent reorganization of Robert E. Lee‘s army in late May, the much depleted brigade of Tigers was consolidated with the “Pelican Brigade,” formally known as the Second Louisiana Brigade, which had also lost its commander, Leroy A. Stafford, a long-time Tiger. Zebulon York became the new commander.

The nickname Tigers subsequently came to encompass all Louisiana infantry troops that fought under Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia. Nearly 12,000 men served at one time or another in various regiments that were destined to be part of the Louisiana Tigers. The name was at times also used for other Louisiana troops, including Levi’s Light Artillery Battery and Maurin’s Battery, but it was the infantry that is most often associated with the term.

Later, York’s consolidated brigade of Tigers fought in Early’s army during the Battle of Monocacy and several subsequent battles in the Shenandoah Valley. In late 1864, the Tigers returned to the Army of Northern Virginia in the trenches around Petersburg, Virginia. By the Appomattox Campaign, many regiments were reduced to less than 100 men apiece, and Brig. Gen. William R. Peck had become the Tigers’ final commander.

Postbellum

Following the Civil War, many former Tigers joined the Hays Brigade Relief Association, a prominent New Orleans social and political organization. Harry T. Hays, by then the local sheriff, mobilized the association during the 1866 New Orleans Race Riot. A company of former Louisiana Tigers joined the Fenian Invasion of Upper Canada on June 1, 1866, and fought the Canadian militia the next day at the Battle of Ridgeway.

State of Louisiana monument at Gettysburg

Confederate Monuments at Gettysburg

The State of Louisiana monument is southwest of Gettysburg on West Confederate Avenue, across from Pitzer’s Woods. (Tour map: West Confederate Avenue – Part 4) It was dedicated on June 11, 1971. A nearby marker bears a tablet with the names of the commission responsible for the monument.

Louisiana sent over 3,000 men to Gettysburg with the Army of Northern Virginia. Around 725 became casualties. It was the seventh largest contingent and the seventh highest casualties of the twelve Confederate states at Gettysburg (see the States at Gettysburg).

State of Louisiana monument at Gettysburg

The monument is entitled “Spirit Triumphant.” It was created by Donald DeLue, who was also the sculptor of the State of Mississippi monument and the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors monument. The sculpture represents a wounded gunner of New Orleans Washington Artillery clutching a Confederate battle flag to his heart. Above him the Spirit of the Confederacy sounds a trumpet and raises a flaming cannonball.

Location of the Louisiana monument at Gettysburg

The State of Louisiana monument is south of Gettysburg on the east side of West Confederate Avenue. It is about 175 yards north of Millerstown Road. West Confederate Avenue is one way southbound at this point. (39°48’10.7″N 77°15’21.0″W)