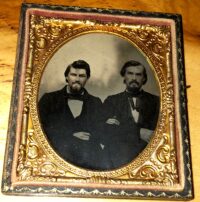

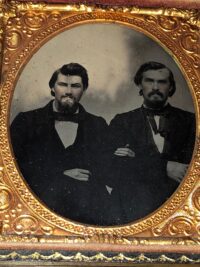

Id’d Ambrotype of Captain Josiah Moore and His Brother, Thomas Moore Both Ill. Inf. Officers

SOLD

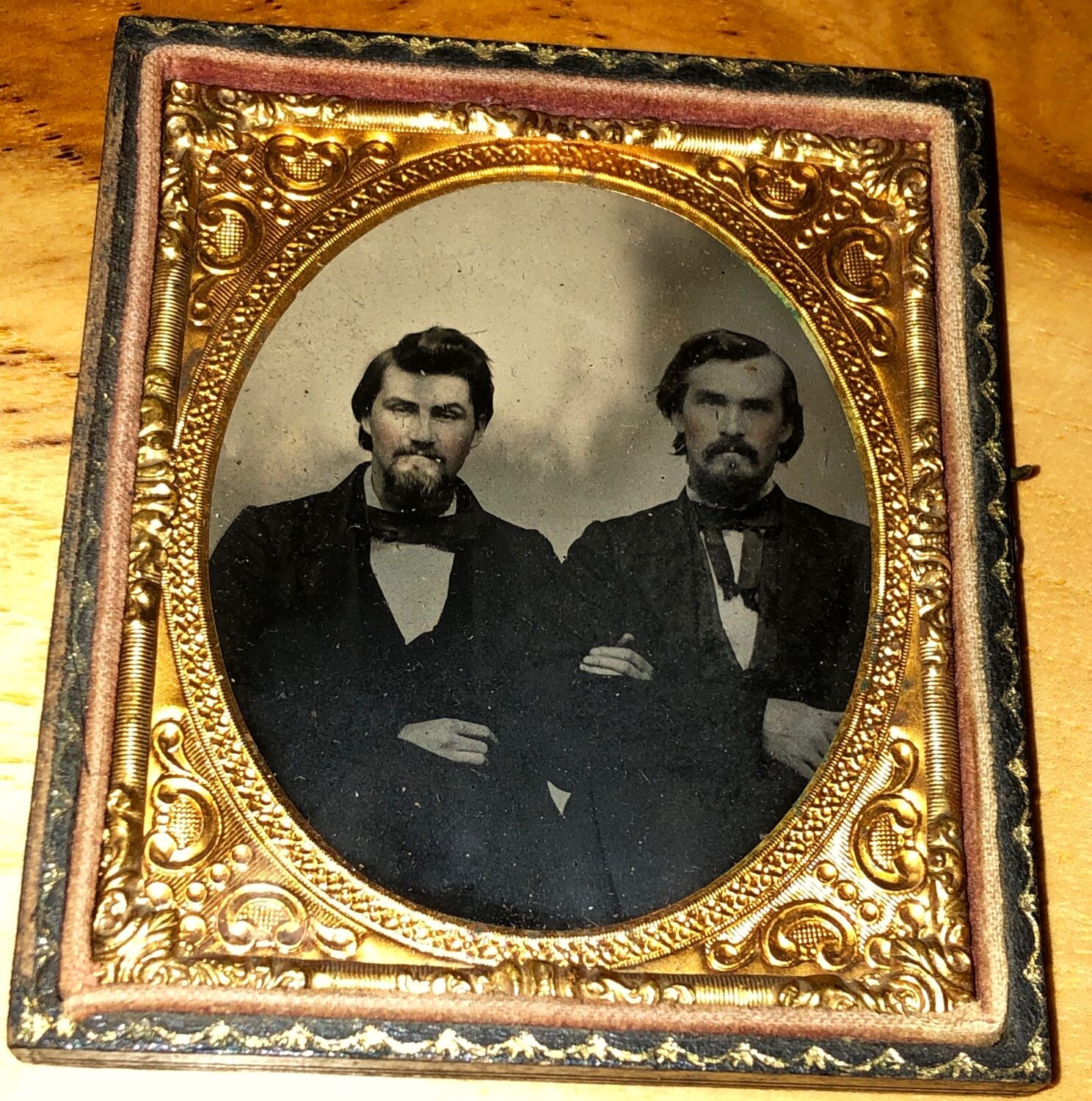

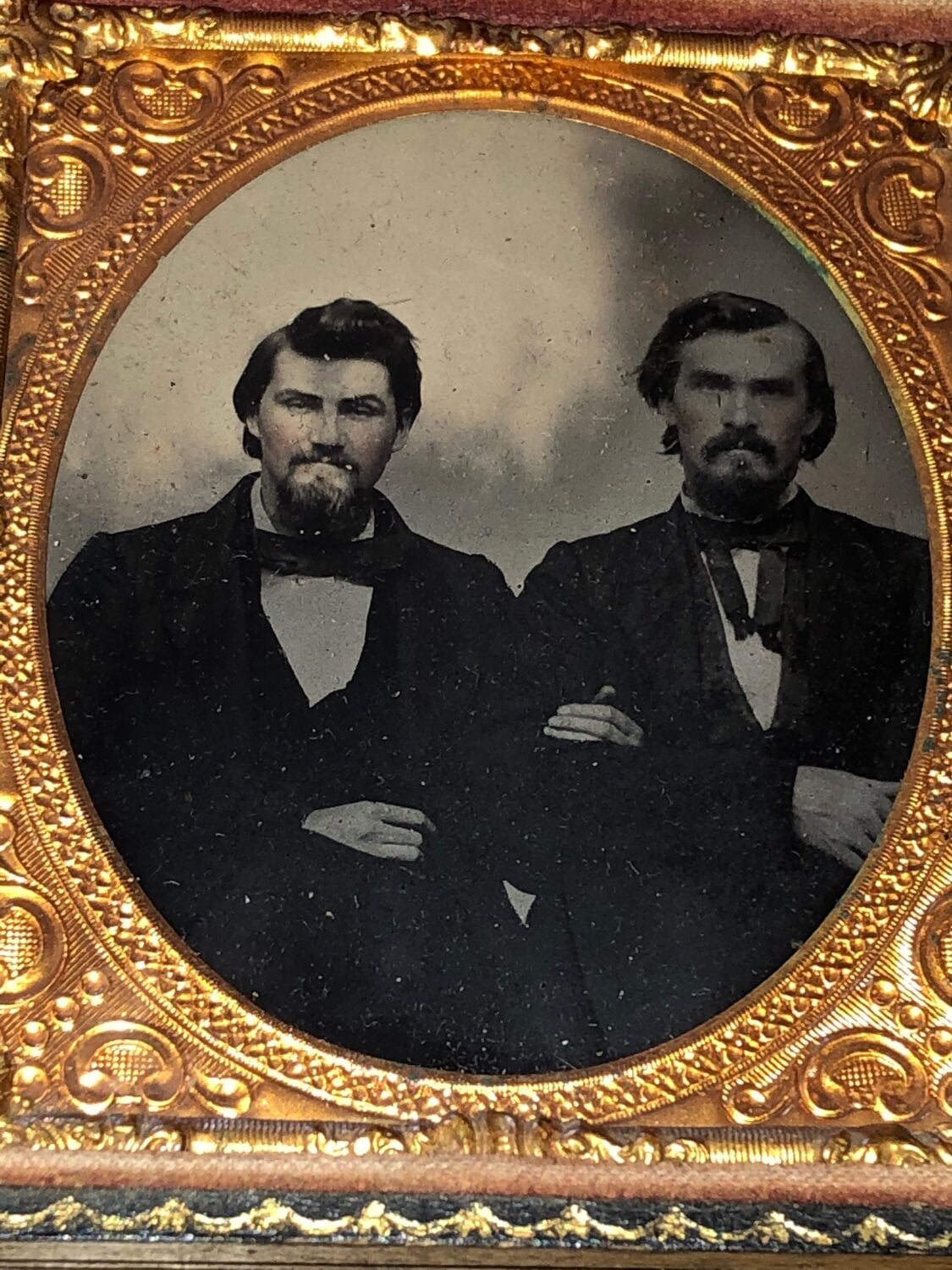

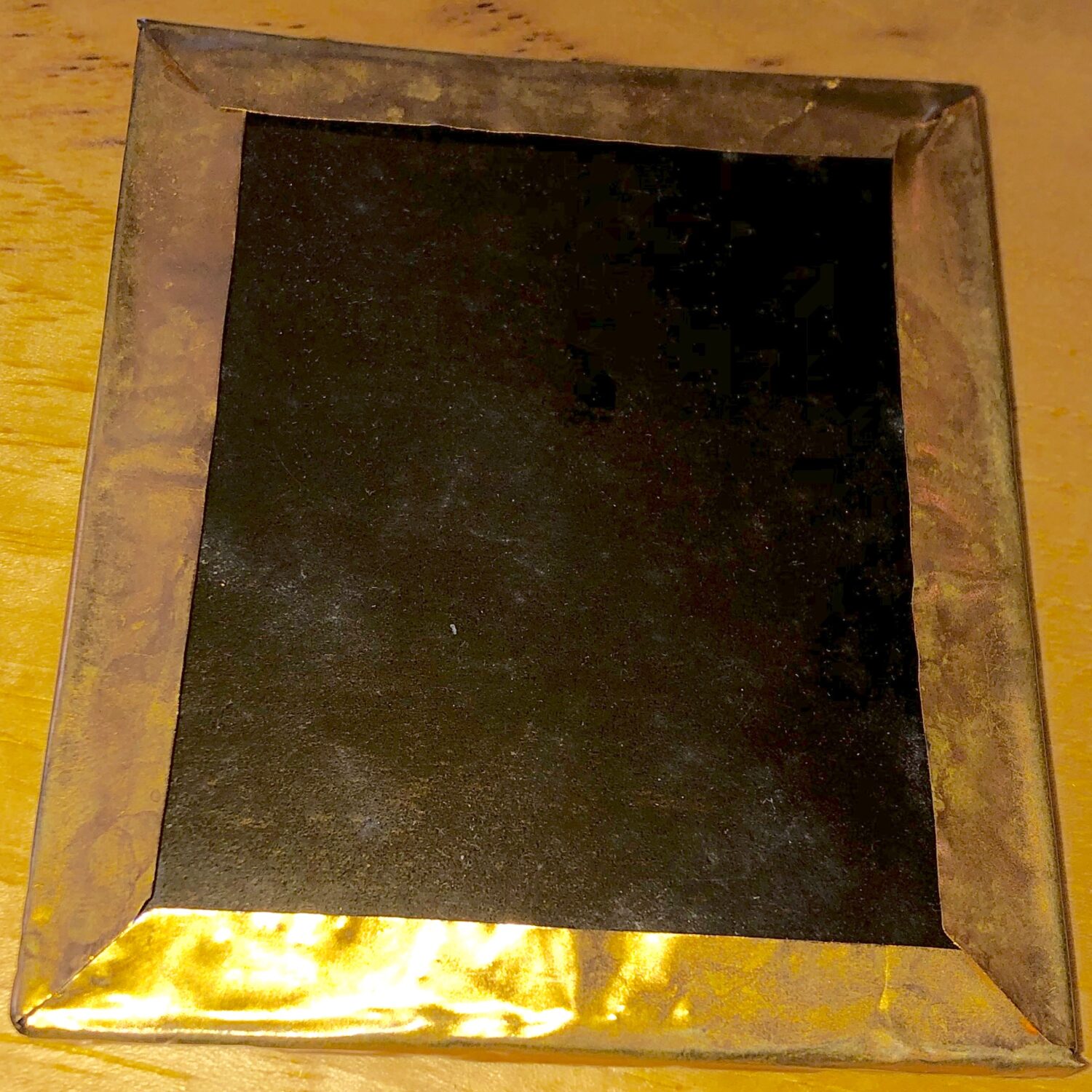

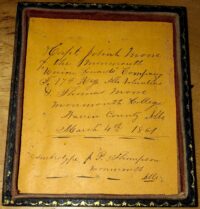

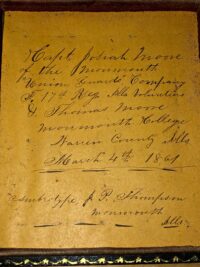

Id’d Ambrotype of Captain Josiah Moore and His Brother, Thomas Moore Both Ill. Inf. Officers – In this pre-war, sixth plate ambrotype, both Josiah and his brother Thomas Moore are depicted in civilian garb, just prior to Josiah’s enlistment in the 17th Illinois Infantry. The image is in excellent condition; behind the half cased image, written in pencil, in the period, on the paper attached to the interior of the case is the following:

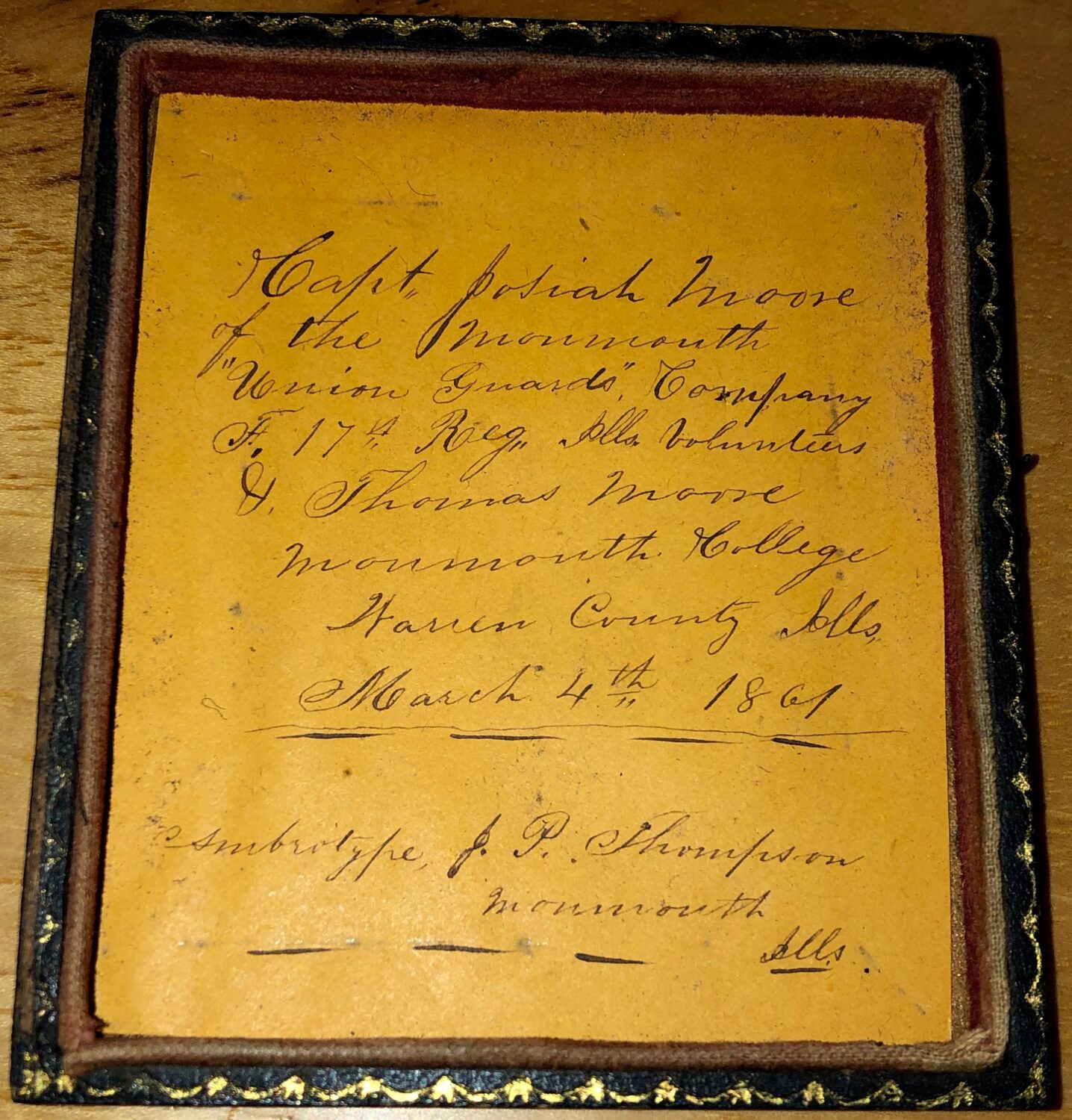

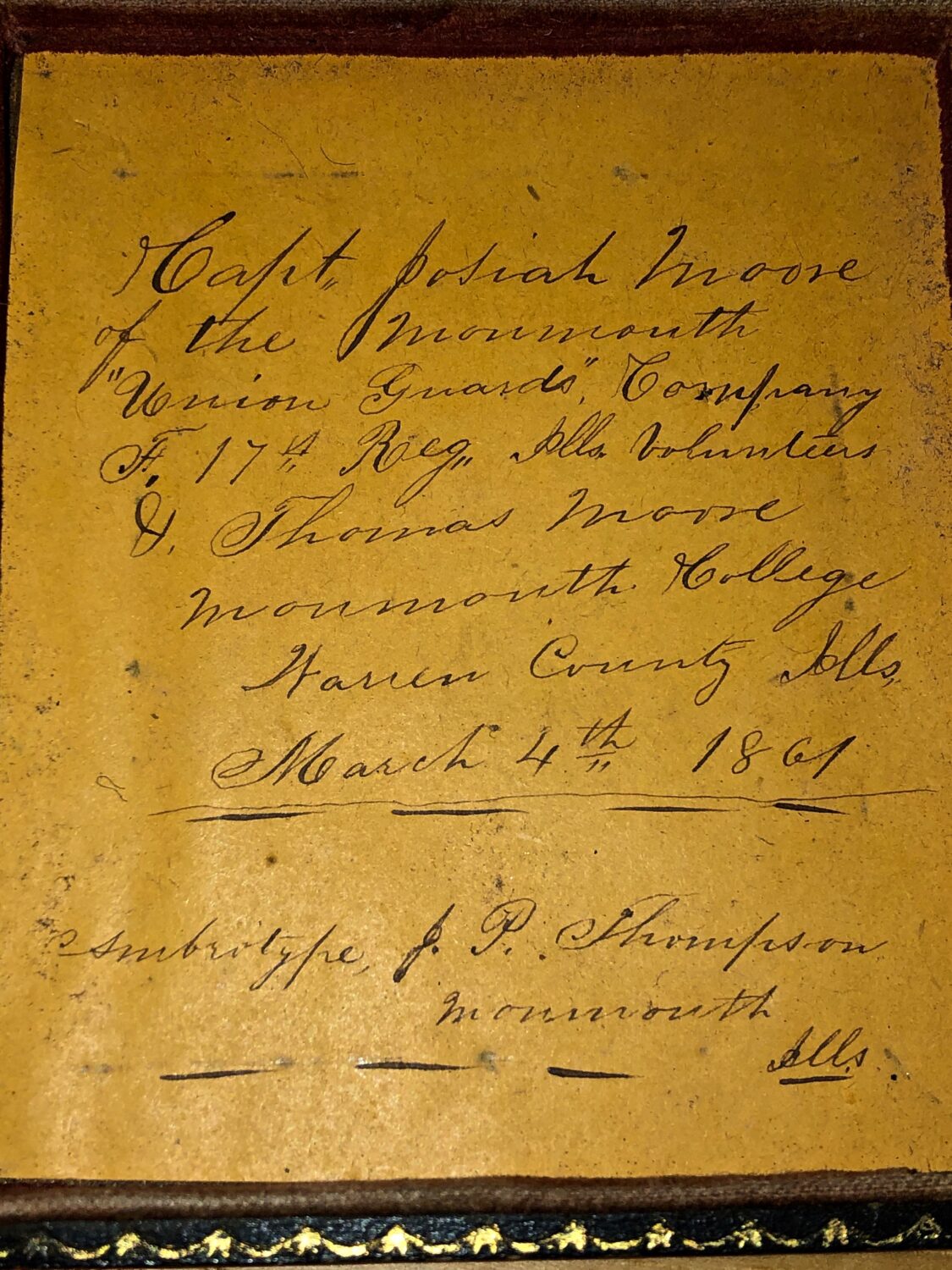

“Capt. Josiah Moore

of the Monmouth

‘Union Guards’ Company

- 17th Reg. Ills. Volunteers

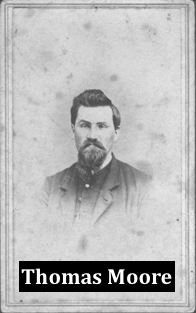

Thomas Moore

Monmouth College

Warren County Ills

March 4th 1861

________ _______ ________ _______

Ambrotype J.P. Thompson

Monmouth

Ills”

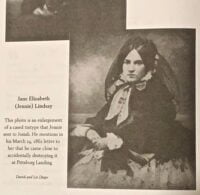

_______ ________ _______ _______

In 1862, Thomas Moore would also join the war effort when he enlisted in the Co. E of the 96th Illinois Infantry. Both of the Moore brothers would survive the war; in their respective units, both were engaged in significant combat. Josiah’s wartime correspondence between him and his future wife, Jennie Lindsay, has been collected and printed in the book “A Civil War Captain and His Lady: Love, Courtship, and Combat from Fort Donelson through the Vicksburg Campaign”*, edited and interpreted by Gene Barr. We will provide a copy of this interesting and poignant book to the purchaser of this image. The photographer, J.P. Thomson**, was a significant photographer in Illinois, in the 1850s and at the onset of the Civil War; Thompson (misspelled “Thompson” on the paper behind the image). In October of 1858, Thomson would take a photograph of Abraham Lincoln who had come to Monmouth to deliver a speech. By 1862, Thomson closed his photography business.

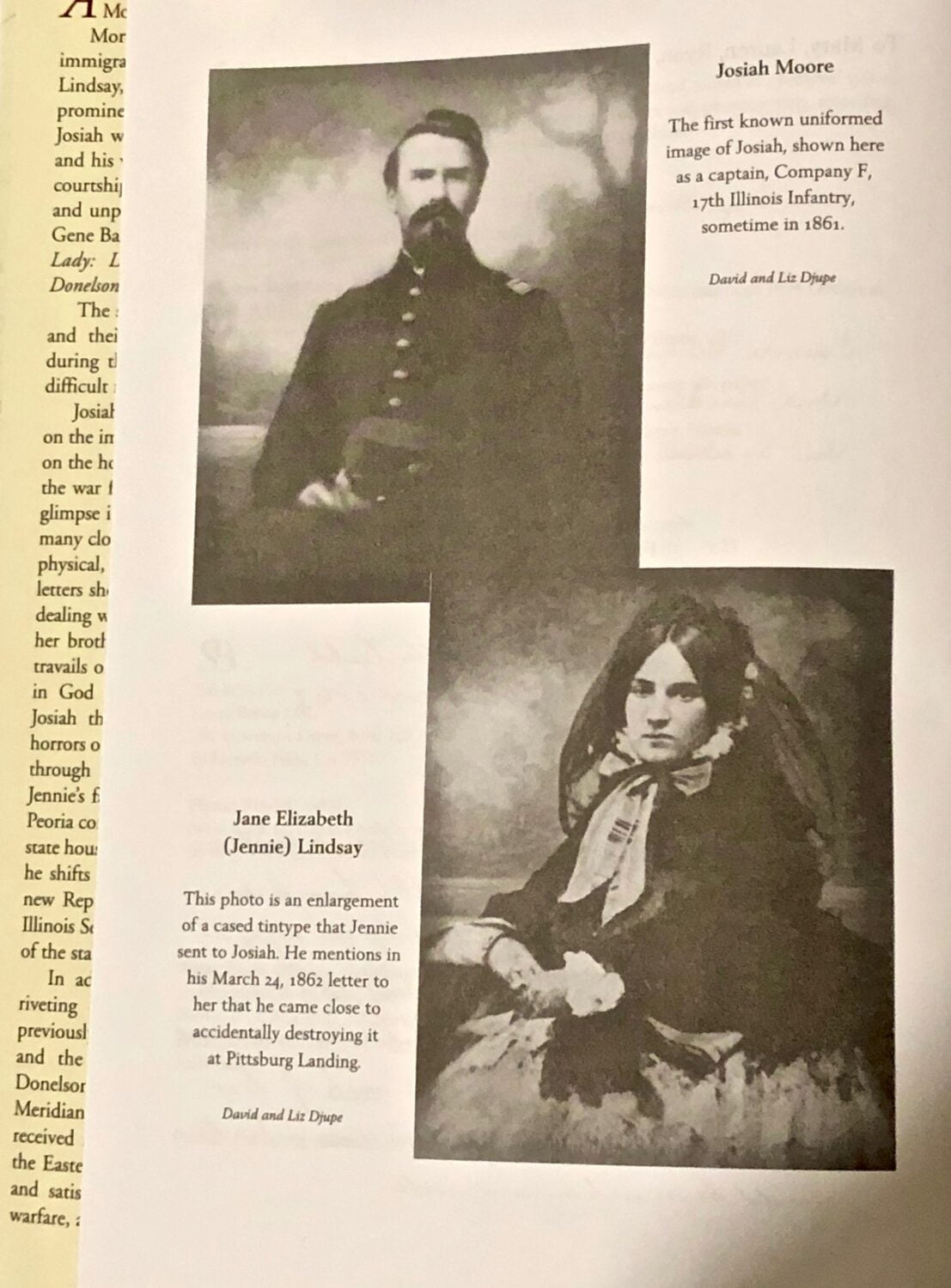

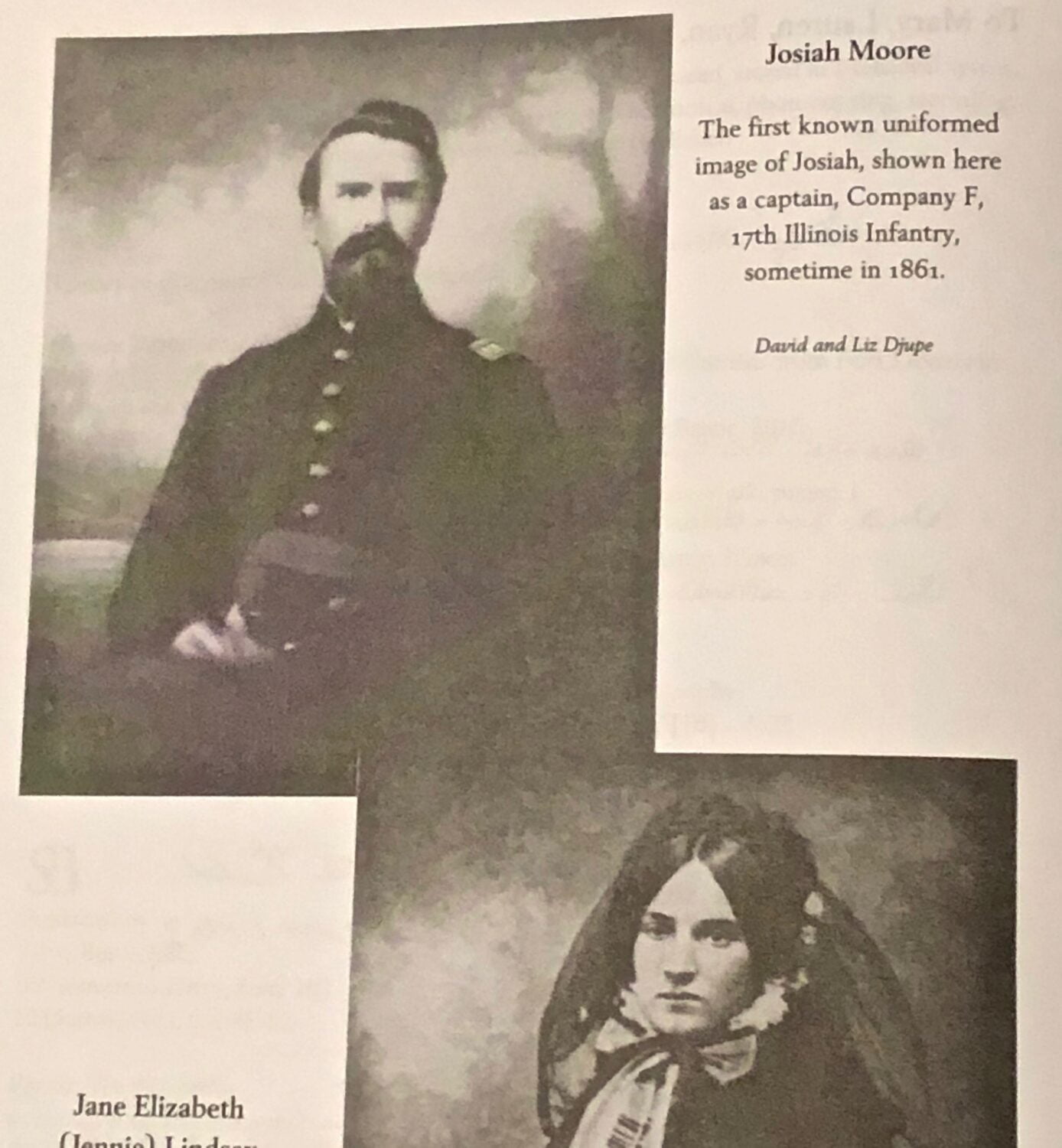

Josiah Moore

| Residence Hanover IL; Enlisted on 4/20/1861 as a Captain. On 5/25/1861 he was commissioned into “F” Co. IL 17th Infantry He was Mustered Out on 6/15/1864 Other Information: Member of GAR Post # 676 (Lake Forest) in Lake Forrest, IL died 2/9/1897 |

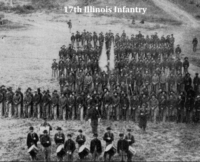

17th IL Infantry

( 3-years )

| Organized: Peoria, IL on 5/24/61 Mustered Out: 6/4/64 at Springfield, ILOfficers Killed or Mortally Wounded: 3 Officers Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 1 Enlisted Men Killed or Mortally Wounded: 71 Enlisted Men Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 71 (Source: Fox, Regimental Losses) |

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comment |

| Aug ’61 | Oct ’61 | Military Dist Cairo | Army and Dept of the Tennessee | New Organization | ||

| Oct ’61 | Feb ’62 | 5 | Military Dist Cairo | Army and Dept of the Tennessee | ||

| Feb ’62 | Feb ’62 | 3 | 1 | Military Dist Cairo | Army and Dept of the Tennessee | |

| Feb ’62 | Jul ’62 | 3 | 1 | District and Army of West Tennessee | ||

| Jul ’62 | Sep ’62 | 3 | 1 | District of Jackson | District and Army of West Tennessee | |

| Sep ’62 | Nov ’62 | Unattached | District of Jackson | District and Army of West Tennessee | ||

| Nov ’62 | Dec ’62 | 4 | 3 | Right Wing, 13 | District and Army of West Tennessee | |

| Nov ’62 | Dec ’62 | 1 | 6 | Left Wing, 13 | District and Army of West Tennessee | |

| Dec ’62 | Jan ’63 | 1 | 6 | Left Wing, 16 | Department of the Tennessee | |

| Jan ’63 | May ’63 | 1 | 6 | 17 | Department of the Tennessee | |

| Jul ’63 | Apr ’64 | 3 | 3 | 17 | Department of the Tennessee | |

| Apr ’64 | Jun ’64 | Maltby’s | District of Vicksburg | Department of the Tennessee | Mustered Out |

ILLINOIS

SEVENTEENTH INFANTRY.

(three years)

| The Seventeenth Regiment Of Illinois Infantry Volunteers was mustered into the United States service at Peoria Ill., on the 26th day of May, 1861. Left camp on the 17th of June for Alton, Ill., for the purpose of more fully completing its organization and arming. Late in July it proceeded from Alton to St. Charles, Mo., remaining but one day; thence went to Warrenton, Mo. where it remained in camp about two weeks – Company “A” being detailed as body guard to General John Pope, with headquarters at St. Charles. The Regiment left Warrenton for St. Louis, and embarked on transports for Bird’s Point, Mo. Remained at Bird’s Point some weeks’ doing garrison duty; then proceeded to Sulphur Springs Landing debarking there, proceeded, via Pilot Knob and Ironton, to Fredericktown, Mo., in pursuit of General Jeff Thompson, and joined General B. M. Prentiss, command at Jackson, Mo.; thence proceeded to Kentucky and aided in the construction of Fort Holt; then ordered to Elliott’s Mills; remained there a short time and returned to Fort Holt; thence to Cape Girardeau, and with other Regiments were again sent in pursuit of General Jeff. Thompson’s forces. Met and defeated them at Frederick town, Mo., October 21, 1861, losing several killed and wounded. The Regiment charged the enemy’s lines early in the engagement, completely routing him. Captured two 6-pound howitzers and 200 prisoners. The enemy fled in great confusion, leaving his dead upon the field among whom was the Brigade Commander, Colonel Lowe. Among the killed and wounded on the Union side was First Lieutenant J. Q. A. Jones, Company “K”, killed ; Second Lieutenant Owen Wilkins , Company ‘A’ wounded, and Sergeant Jacob Wheeler, Company “K,” was twice wounded, once dangerously. October 22, pursued the enemy, and engaged him near Greenfield, Ark., which the Seventeenth lost one killed and several wounded. Returned to Cape Girardeau, doing provost duty until early in February. 1862, when ordered to Fort Henry. Participated in the sanguinary battle, followed by the surrender of Fort Donelson, losing a number of men; thence marched to Metal Landing; thence embarked for Savannah, later arriving at Pittsburgh Landing, where the Regiment was assigned to the First Division of the Army of West Tennessee, under command of General John A. McClernand, and upon the memorable field of Pittsburgh Landing took part in the momentous battles of the 6th and 7th of April. On the 6th the Regiment was under fire from early morn until night, when a rain set in. Meanwhile under the dauntless and skillful leading of General McClernand, the field contested with fluctuating success in seven successive positions. At nightfall he formed his decimated ranks for the eighth time upon the Seventeenth Regiment to rest on their arms until the morning of the 7th, when the Regiment with the Division moved forward to the attack, and in co-operation with the other Union forces, after a fierce and stubborn conflict, drove the enemy from the field. it is a notable fact that the First Division, including the Seventeenth Regiment, maintained its organization, not only amid the wreck and confusion of the 6th, but also on the 7th. It fought out the two days, battle. Had not this been so, the Union forces must have been overwhelmed on the first day, and to General McClernand, perhaps more than to any one commander, is due the credit of averting this calamity. In the two days the Seventeenth lost some 130 killed and wounded. The victory won, later the Regiment marched with the advance forces to Corinth. After the evacuation of Corinth, marched to Purdy, Bethel, and Jackson, Tenn. ; remained there until 17th of July, when the Regiment was ordered to Bolivar, and assigned to duty as provost guard. Remained at Bolivar until November, 1862, during which time participated in the expedition to Iuka. to reinforce General Rosecrans. Afterwards at the battle of Hatchie. Returned again to Bolivar; remained there until middle of November. Then ordered to Lagrange, reporting to Major General John A. Logan; were assigned to duty as provost guard, Colonel Norton being assigned to the command at that post. Early in December marched to Holly Springs; thence to Abbeyville, guarding railroads; thence to Oxford. After the capture of Holly Springs, was assigned to the Sixth Division, Seventeenth Army Corps, under Major General McPherson; then proceeded, via Moscow, to Collierville, from there to Memphis, and was assigned to duty at the navy yard. Remained there until January 16; then embarked for Vicksburg; re-embarked and proceeded to Lake Providence, La., then the headquarters Of the Seventeenth Army Corps, doing duty there until the investment of Vicksburg commenced. Arriving at Milliken’s Bend on or about May 1st, commenced to march across the Delta to Perkins, Landing, on the Mississippi river; thence to crossing below Grand Gulf, advancing with McPherson’s command, via Raymond Champion Hills, Jackson, Big Black, and to the final investment of Vicksburg. After the surrender of that city, remained there doing garrison duty and making incursions into the enemy’s country as far east as Meridian; west as far as Monroe, La. Returning to Vicksburg, remained there until May, 1864- the term of service of the Regiment expiring on the 24th of May, of that year. The Regiment was ordered to Springfield, Ill., for muster- out and final discharge, when and where those of the original organization who did not re-enlist as veterans were mustered out and discharged. A sufficient number not having re-enlisted to entitle them to retain their regimental organization, the veterans and recruits whose term of service had not expired were consolidated with the Eighth Illinois Infantry Volunteers, and were finally mustered out with that Regiment and discharged in the spring of 1866. |

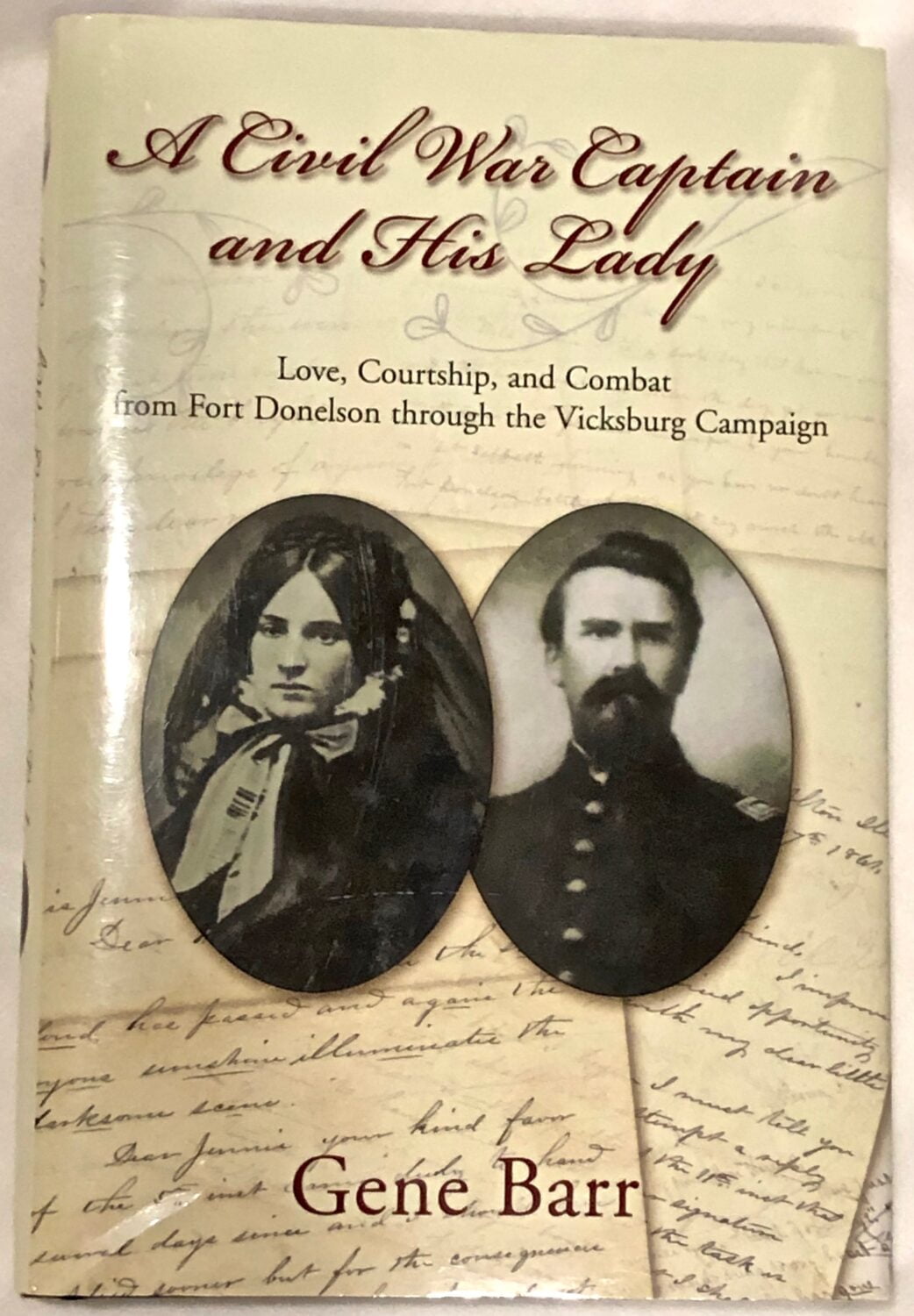

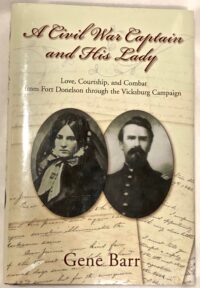

*A Civil War Captain and His Lady by Gene Barr – A Civil War Captain and His Lady is a true “Cold Mountain” love story from the Northern perspective.

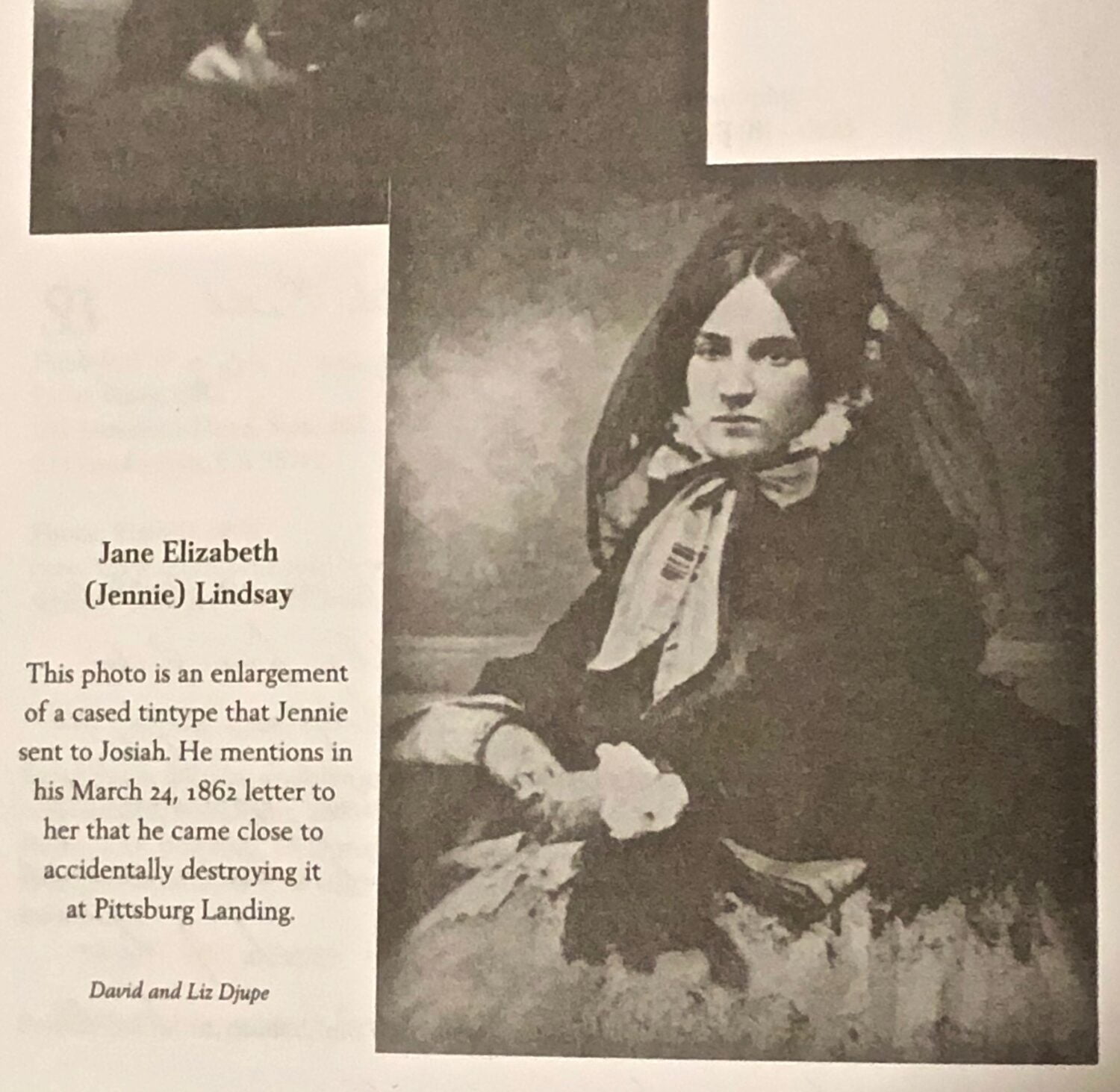

More than 150 years ago, 27-year-old Irish immigrant Josiah Moore met 19-year-old Jennie Lindsay, a member of one of Peoria, Illinois’s most prominent families. The Civil War had just begun, Josiah was the captain of the 17th Illinois Infantry, and his war would be a long and bloody one. Their courtship and romance, which came to light in a rare and unpublished series of letters, forms the basis of Gene Barr’s memorable “A Civil War Captain and His Lady: Love, Courtship, and Combat from Fort Donelson through the Vicksburg Campaign”.

The story of Josiah, Jennie, the men of the 17th and their families tracks the toll on our nation during the war and allows us to explore the often difficult recovery after the last gun sounded in 1865.

Josiah’s and Jennie’s letters shed significant light on the important role played by a soldier’s sweetheart on the home front, and a warrior’s observations from the war front. Josiah’s letters offer a deeply personal glimpse into army life, how he dealt with the loss of many close to him, and the effects of war on a man’s physical, spiritual, and moral well-being. Jennie’s letters show a young woman mature beyond her age dealing with the difficulties on the home front while her brother and her new love struggle through the travails of war. Her encouragement to keep his faith in God strong and remain morally upright gave Josiah the strength to lead his men through the horrors of the Civil War. Politics also thread their way through the letters and include the evolution of Jennie’s father’s view of the conflict. A leader in the Peoria community and former member of the Illinois state house, he engages in his own political wars when he shifts his affiliation from the Whig Party to the new Republican Party, and is finally elected to the Illinois Senate as a Peace Democrat and becomes one of the state’s more notorious Copperheads.

In addition to this deeply moving and often riveting correspondence, Barr includes additional previously unpublished material on the 17th Illinois and the war’s Western Theater, including Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and the lesser known Meridian Campaign—actions that have historically received much less attention than similar battles in the Eastern Theater. The result is a rich, complete, and satisfying story of love, danger, politics, and warfare, and it is one you won’t soon forget.

Thomas Moore

| Residence Scales Mound IL; Enlisted on 8/15/1862 as a Private. On 9/4/1862 he mustered into “E” Co. IL 96th Infantry He was Mustered Out on 6/10/1865 at Nashville, TN

96th IL Infantry

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ILLINOIS

|

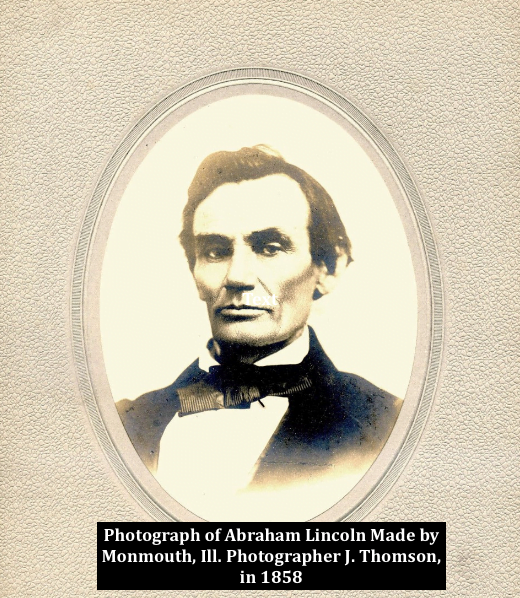

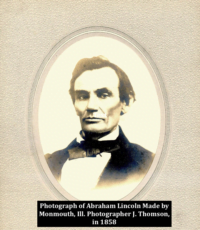

**‘Developing’ the history of Monmouth’s Lincoln photograph

MONMOUTH, Ill. —On Oct. 11, 1858, Abraham Lincoln delivered a senatorial campaign speech in Monmouth, following which a local photographer took his portrait. Recently, I was contacted by a great-great-grandnephew of that photographer, living in Los Angeles. His inquiries caused me to review the historical information I have about Lincoln’s visit and the Monmouth portrait.

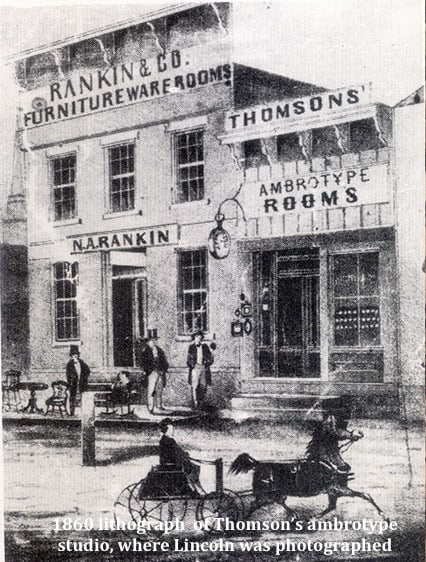

David Thomson Jones is the great-great grandson of Hugh Laughlin Thomson, an Ohio native who settled near Biggsville in 1852 and served eight years as Henderson County circuit clerk. Hugh Thomson’s brother, William Judkins Thomson, came to Monmouth from Pennsylvania in 1856, where he established an ambrotype studio on the south side of the Public Square, just east of Main Street. Ambrotypes were portraits on glass that bridged the technological gap between daguerreotypes and dry plate negatives.

The Thomsons were devout Presbyterians and active in the new Republican Party. William Judkins Thomson was one of several Republican leaders who welcomed Lincoln to Monmouth and shared dinner with him at the Baldwin House hotel, prior to his afternoon speech. An article in the Nov. 26, 1884, edition of the Monmouth Evening Gazette stated that Thomson was “a friend of Mr. Lincoln” and persuaded him “to sit for a negative.”

Lincoln’s Oct. 11 visit to Monmouth followed a similar visit to Monmouth by his opponent, Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, Oct. 5, during which he spoke on the Public Square. On Oct. 7, Lincoln debated “The Little Giant” at Knox College. On Oct. 9, he spoke at Oquawka and Burlington, Iowa. On the morning of Oct. 11, he took the train from Burlington to Monmouth. Arrangements had been made for a huge gathering to welcome him on the Oquawka road, but torrential rains had washed away those plans.

Lincoln was met at the Monmouth CB&Q depot by circuit clerk William S. Laferty, who had a carriage waiting, but despite the rain, Lincoln elected to walk the seven blocks to the Baldwin House on East Broadway. A Monmouth correspondent for the Chicago Tribune wrote that rain continued to fall, and that until 1 p.m. it was assumed that no one from the country would show up for the speech, so it would be moved indoors to a hall. About noon, however, large crowds began forming and it became apparent the speech had to be given outdoors. A stage had been constructed on the Public Square, but according to eyewitness Harry B. Young, the location “was changed to the lumber yard at the corner of East Fourth Avenue and South First street, because the square was a sea of mud. A stage was built for the speaker and when the rain came up an improvised top of rough boards, slanting in order to let the rain run off, was made for it.”

The Tribune correspondent noted that Lincoln spoke for three hours, with the entire audience seemingly “perfectly wrapt in attention.” The reporter for the Monmouth Review (a Democratic paper), however, described the speech as “coldly received by the small crowd present.”

Just what time the speech ended is uncertain, but it seems likely that Lincoln’s next destination was Thomson’s ambrotype studio, as daylight probably would have been required to capture the portrait. In a 1932 letter to Monmouth photographer Fleming Long, Alexander S. Thomson, a nephew of the photographer (who was 14 during Lincoln’s visit) recalled assisting his uncle in the studio that day. He began his recollection by mentioning the speaker’s stand was in front of his uncle’s studio, so perhaps Lincoln delivered some additional remarks from the original stage before having his photo taken.

After Lincoln finished his address, the nephew recalled, “he threw his cloak around himself and came into the front room of the studio where many politicians followed him. Uncle invited him into the back gallery, closing the door on the crowd. As he came in I placed a chair for him to sit down and wait a little while Uncle was preparing for him. As he sat down he took me by the hand, asked my name and asked about my school work and other things along the line of boy talk. … When Uncle had placed him in position, I was standing at one side, a little back but where I could see plainly. I saw him as he sat on the chair, the same as you see him in the picture.”

Alexander Thomson’s 1937 obituary notes that in later years, he spoke about “the uncanny carrying powers of Lincoln’s high pitched voice, the outstretching of his enormous right arm as his chief gesture, and the great hand waving for silence. It was the proudest moment of his young life as he led Lincoln from the platform to his uncle’s shop and watched the taking of the picture, which was a laborious process in those days.”

According Monmouth historian Emily Roberts Hubble, William Laferty entertained Lincoln with a two-hour reception in his home across from the Baldwin House “when the exercises were over in the afternoon.” While it’s possible the reception occurred before the portrait was taken, it seems more reasonable to assume the photo was taken first, as the sun set on that date at approximately 5:30.

On the 70th anniversary of the speech in 1927, the Review Atlas interviewed the photographer’s son, John N. Thomson, who was just 2 at the time of the photo, but whose older brother William was 6. He recalled that after the photo Lincoln took William next door (to N.A. Rankin’s store) and “filled him with candy and figs.”

William Judkins Thomson would abandon the photography business by 1862 and become Warren County clerk, serving in that post until 1866. He died in 1869 at the relatively young age of 46. While the cause of his death is uncertain, one wonders if it might have been related to his use of carcinogenic chemicals. The ambrotype process used cadmium compounds, which, according to Monmouth College chemical hygiene officer Kathy Mainz, are potentially hazardous, as are other chemicals used in the process, including ammonium bromide, dimethyl ether, glacial acetic acid, potassium cyanide and bichlorate of mercury. In 1896, when journalist Ida Tarbell was writing her 20-part series on Lincoln for McClure’s Magazine, Thomson’s widow, Margaretta, was asked to lend the Lincoln ambrotype to be sent to New York City for an engraving to illustrate the article, but she refused. Eventually, through the intervention of Col. Clark E. Carr of Galesburg and State Sen. Fred E. Harding of Monmouth, she allowed the picture to be copied by Galesburg photographer Thomas Harrison, who forwarded a print to McClure’s.