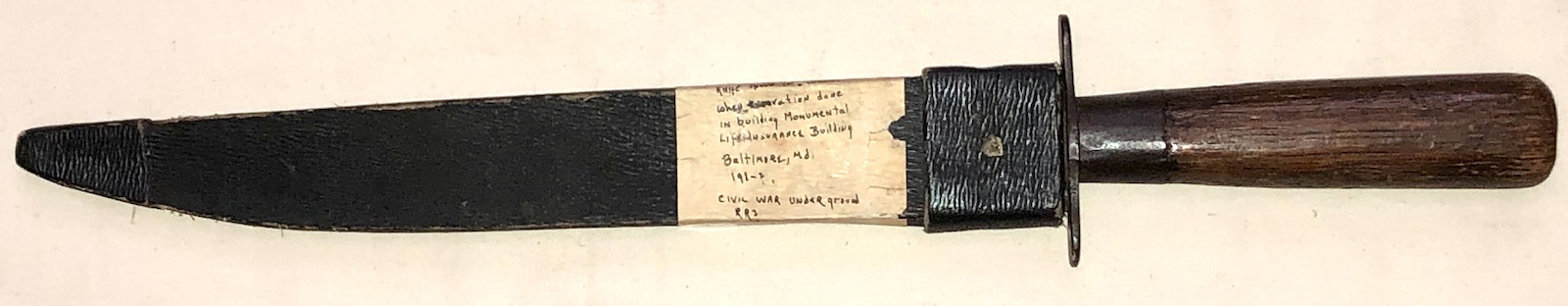

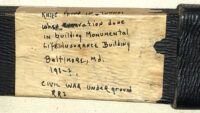

Confederate Side Knife and Sheath Discovered in the 1920s in a Tunnel During the Construction of the Monumental Life Insurance Building in Baltimore

SOLD

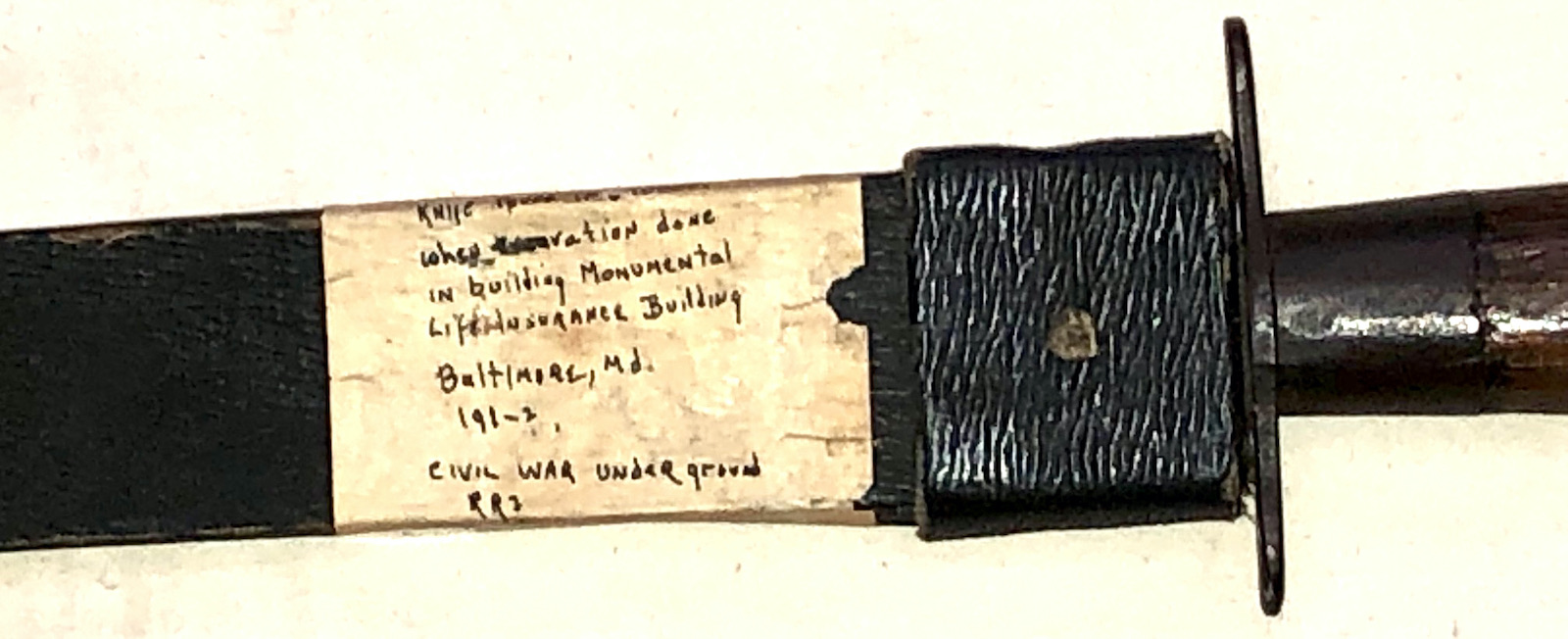

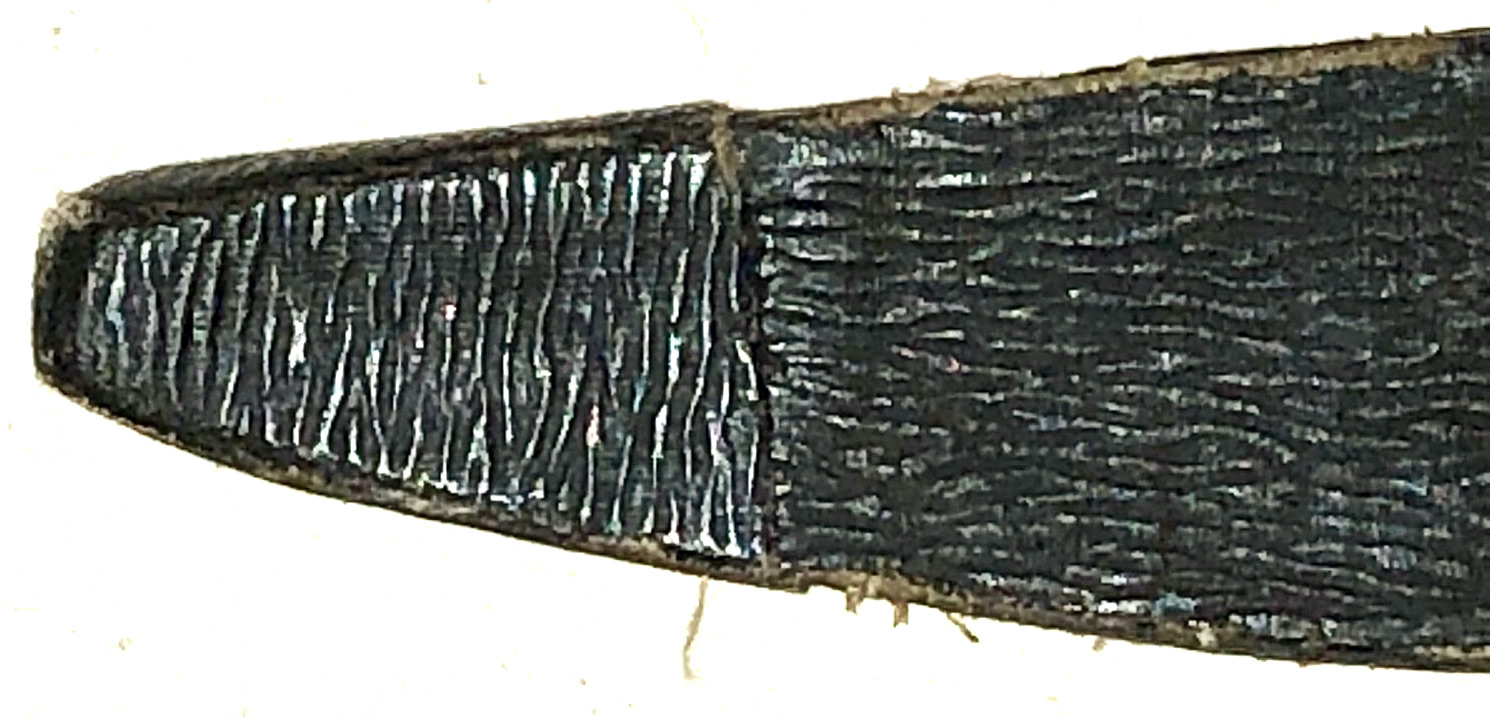

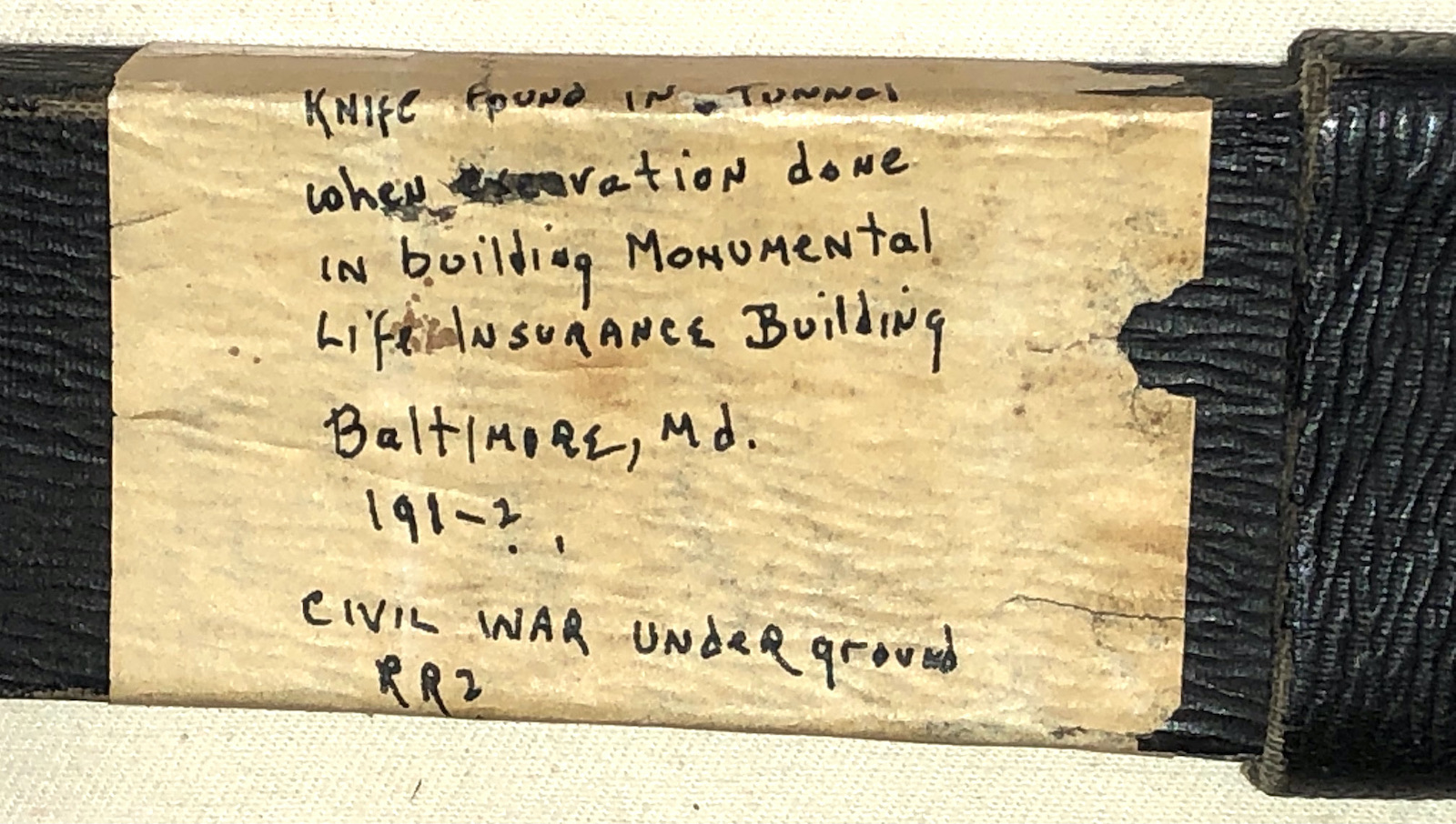

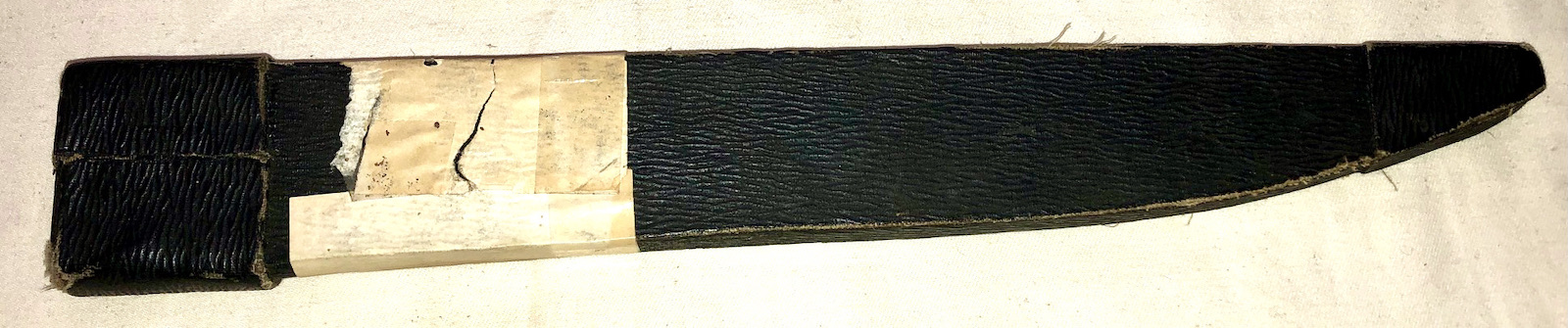

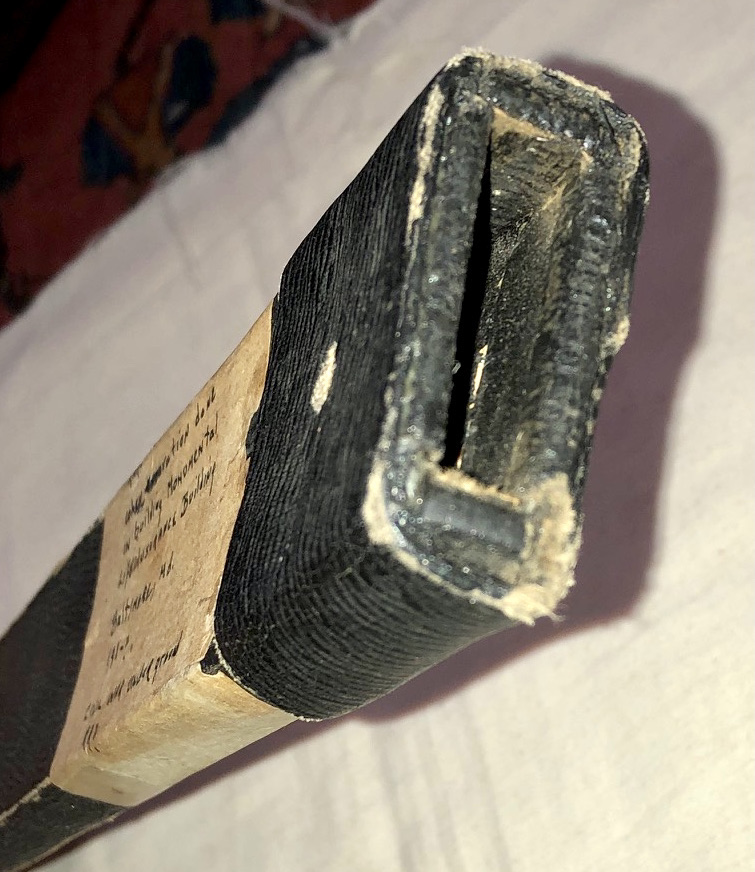

Confederate Side Knife and Sheath Discovered in the 1920s in a Tunnel During the Construction of the Monumental Life Insurance Building in Baltimore – This fine example of a Confederate side knife, retaining its original, rare sheath, was, according to an old, hand-inked note pasted on the sheath, discovered in a tunnel, during the construction of the foundations of the Monumental Life Insurance Building in Baltimore, around 1928. Numerous caves and tunnels have been discovered beneath sections of Baltimore, some of natural origins and some man-made – note the attached articles discussing the caverns and caves that once existed beneath the urban expanse of Baltimore*. The knife appears to be a substantial side knife, with a considerably heavy blade; the tang has been peened into either a walnut or oak handle, that has a simple, iron cross guard. The end of the tang is within a small, brass square at the distal end of the handle. The sheath, which remains in superior condition, is comparable in construction to mid-19th century, image case coverings – it appears to be heavy pasteboard or perhaps thin wood, covered in a figured, thin leather; the sheath has a doubled surround at the cross guard area, with what appears to be the location of what was a belt frog stud; the tip of the sheath is also double covered. The knife blade, seemingly blacksmith made is, as mentioned, quite substantial, with a thick, flat spine; the blade, presenting a single, stopped fuller, crudely ground into place, remains in overall good condition, exhibiting some minor surface corrosion. The blade was finished by filing, as numerous file marks are visible, especially in the ricasso area. This is an unusual, Civil War, most likely Confederate side knife that was saved from damage or wear being having been hidden in one of the many tunnels that once existed beneath Baltimore for over 60 years, after the end of the war.

Measurements: OL – 20.25”; Blade L – 13.25”; Sheath L – 14”

*Beginning in 1928 when it was built and for 84 years afterwards, the Monumental Life Insurance Company occupied what was ubiquitously known as the Monumental Life Building. In 2012, however, Monumental Life consolidated offices downtown and moved out of Mt. Vernon. The current owner, Chase Brexton Health Services, bought the building and in short order launched an extensive rehab project.

Monumental Life Insurance Company was founded in Maryland during 1858 and originally offered life and fire insurance. Until 1935 it was known as the Mutual Life Insurance Company of Baltimore, known as the ‘Monumental City’ which inspired the new name. AEGON formed as a holding company in 1989 and included Monumental Life.

Charles Street (Baltimore)

Charles Street, known for most of its route as Maryland Route 139, runs through Baltimore City and through the Towson area of Baltimore County. On the north end it terminates at an intersection with Bellona Avenue near Interstate 695 (I-695) and at the south end it terminates in Federal Hill in Baltimore. Charles Street is one of the major routes through the city of Baltimore, and is a major public transportation corridor. For the one-way portions of Charles Street, the street is functionally complemented by the parallel St. Paul Street (including St. Paul Place and Preston Gardens), Maryland Avenue, Cathedral Street, and Liberty Street.

Though not exactly at the west–east midpoint of the city, Charles Street is the dividing line between the west and east sides of Baltimore. On any street that crosses Charles Street, address numbers start from the unit block on either side, and the streets are identified as either “West” or “East,” depending on whether they are to the west or east of Charles.[4] (The “West” and “East” designations also apply to streets that do not cross Charles Street, but exist on both sides of it.) The entire length of Charles Street is a National Scenic Byway known as Baltimore’s Historic Charles Street.[5][6]

Deep Dive into the Tunnels of Federal Hill

peninsulapost Uncategorized May 7, 2021 5 Minutes

Tunnels were cut into the hill and the slopes to the south, all eventually abandoned and forgotten.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in our print newspaper edition on March 12, 2021.

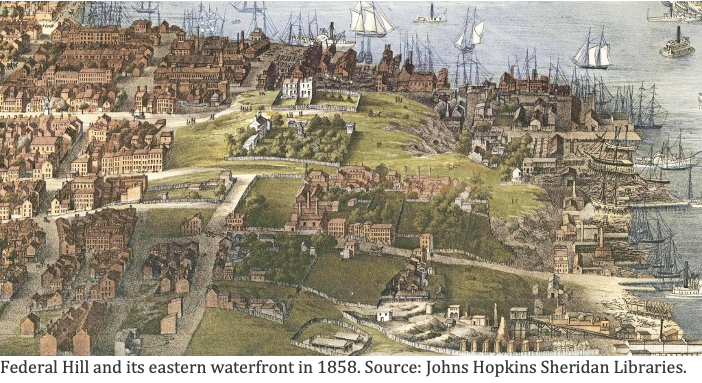

As you see this place today, Federal Hill sits serenely overlooking downtown Baltimore, a broad, terraced grandstand with sweeping views of the harbor below. When the city was young, however, this was a very different place. It was a rough and rutted bluff, worked by industrious men intent on turning a profit from the promontory and its neighboring hills. Tunnels and mines were cut into its flanks, incursions that were eventually abandoned, covered over, forgotten.

But the subterranean voids in and around Federal Hill have refused to stay buried silently in the past. For generations up to the present, their mouths have opened regularly to threaten, startle, and fascinate the living.

‘Mysterious’ urban refuge

Mid-nineteenth century paintings of the hill and adjacent slopes that stretch south along the harbor show extensive gullies and mouths of caves at the crowded waterfront. A “mysterious cave on Federal Hill” was already the stuff of urban lore as far back as 1838, according to a deep dive into the Baltimore Sun archives. Abandoned caves at the foot of the hill provided refuge for the city’s destitute, including one Ann Carey who was found lying in one of the caves in 1852, apparently “with the determination to end her days there.”

The caves and their tunnels that honeycombed the hill and the slopes stretching south from it along the waterfront were dug to extract fine sand and clay used in pottery and glass making. The tunnels also served as cold storage for a Baltimore brewery. Other origin stories have surfaced over the years, but commerce of one sort or another remains the most likely underlying motivation for the widespread excavations.

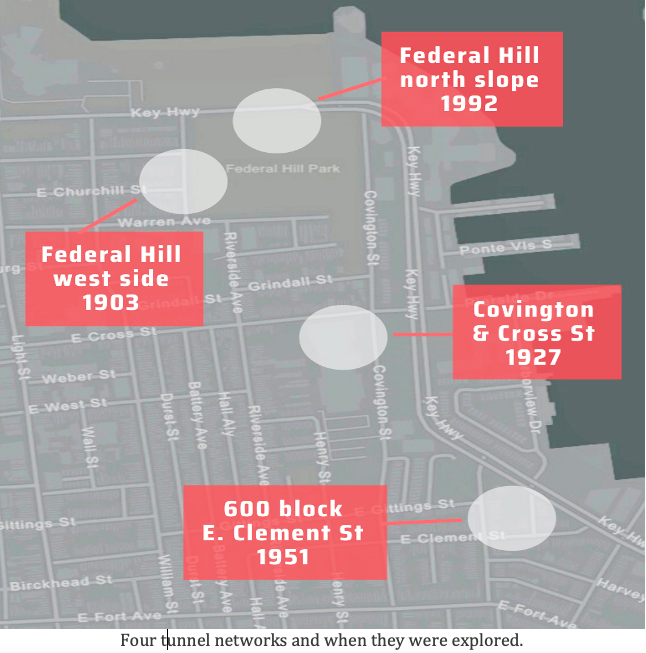

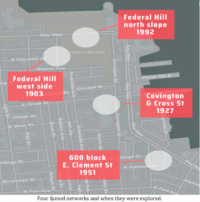

What follows is a tour of four different areas of Federal Hill and its adjacent slopes that have actively burst from the past to the present over the centuries.

Federal Hill was falling down

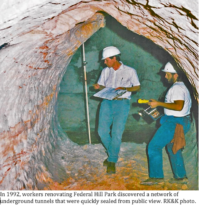

The steep north flank of Federal Hill facing the harbor, which threatened collapse since at least the Civil War, hid an elaborate tunnel network in its upper reaches that was not discovered until the 1990s. A landslide in 1859 after a heavy rain almost completely buried the street below. Continued collapse of the northern flank threatened the Union fort atop Federal Hill in 1864.

The stability of the hill became the city’s headache after Baltimore took it over in 1880 to create Federal Hill Park. Workers at that time had supposedly filled in all the caves, but apparently, they missed a few. The north flank continued to pose a threat with collapses reported in the early 1900s. In 1915, a 12-foot-wide hole opened on this side, which neighborhood boys clambered into until police drove them out.

Cave-ins on and around Federal Hill have attracted public interest for generations. In 1911 this hole in a Battery Avenue sidewalk near Warren St. revealed a tunnel network last visited by local boys 40 years before. Credit: Baltimore Evening Sun

The east side of the hill that now faces the American Visionary Art Museum also posed problems with a landslide in 1972. (A similar but smaller slump of this part of the hill in December 2018 was not tied to tunnels.) Tunnels some 40 feet below the surface of this part of the park were explored in 1952 after a gaping hole suddenly appeared near a walkway at the top of the hill.

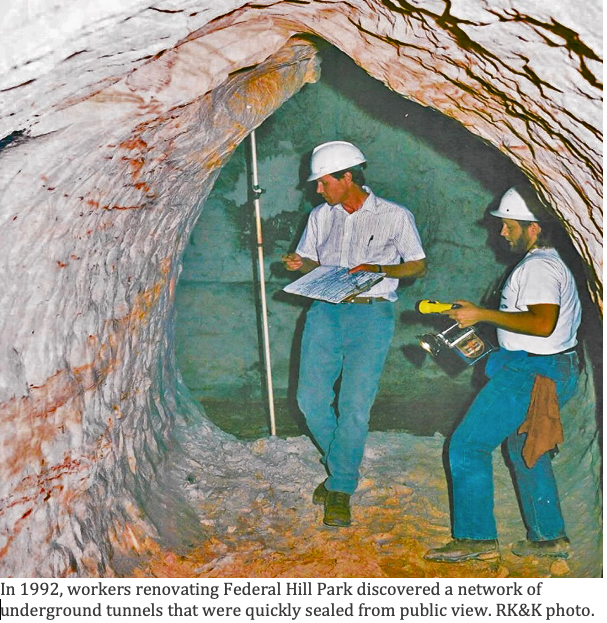

Continuing concerns about the safety of the hill led the city to close Federal Hill Park in the spring of 1992 for a three-year, $1.9 million reconstruction and facelift. That June, workers uncovered an extensive, intact network of underground chambers and corridors which they entered from the north side along the mid-slope walkway. The labyrinth, including a white-walled central chamber 12 feet high, was thoroughly documented by the city before being sealed again, never to be seen by the public or explored by neighborhood boys.

Tunnels surface, west and south

Another, separate tunnel network below the western edge of the hill along Battery Avenue was uncovered in 1903. This “artificial cave” allegedly stretched many blocks south and east underneath Federal Hill Park to the vicinity of Cross and Covington streets. According to news reports of the day, “there are a number of small boys in South Baltimore who have made this trip several times in recent years.” The entrance to this cave near the corner of Battery and Churchill (then Church) Street was also sealed by the property owner.

The buried tunnels in this area continued to vex and amuse residents, however. In 1911 a cave-in near the original entrance left a 15-foot-wide hole in the pavement. Two local men said to have played hide-and-seek in the tunnel network some 40 years before, climbed into the void down a ladder and reported the tunnels just as they remembered them as boys.

The rumored network of tunnels south of Federal Hill near the terminus of Cross Street finally surfaced in 1927 during excavation work for a new building by the United States Printing and Lithographing Company at the intersection of Cross and Covington (current home of Digital Harbor High School). A “labyrinth of tunnels which radiate in every direction from a central stone-vaulted cavern” was mapped, including a tunnel leading north from the property toward Federal Hill.

‘Great Clement Street Caverns’

The most dangerous resurfacing of the area’s subterranean past occurred in 1951 a few blocks south of the high school. The scars of that event are still in plain view today.

The 600 block of E. Clement sits just above Key Highway as the street slowly climbs toward Riverside Avenue. On Sunday, June 10, 1951, residents of several rowhouses on the north side of the block found gaping holes in their cellar floors and nothing but blackness below. Other homes had cracked ceilings and broken walls.

Residents of six adjacent rowhouses abandoned their homes as 100 spectators gathered to watch city workers excavate down into the street to find the cause of the near catastrophe. The state geologist reassured the public that “South Baltimore is steady and firm and is in no danger of disappearing.”

A few days of digging revealed two large caverns beneath the doomed homes and the street. One had “small finger-like tunnels running off it.” Test borings were drilled around the caverns to search for other undiscovered voids, but none were found. The city dumped over 500 tons of fill material into the holes. Six adjacent rowhouses (606-618) were razed. Those lots remain uninhabited today, covered by green space and parking spaces. – Peninsula Post Staff