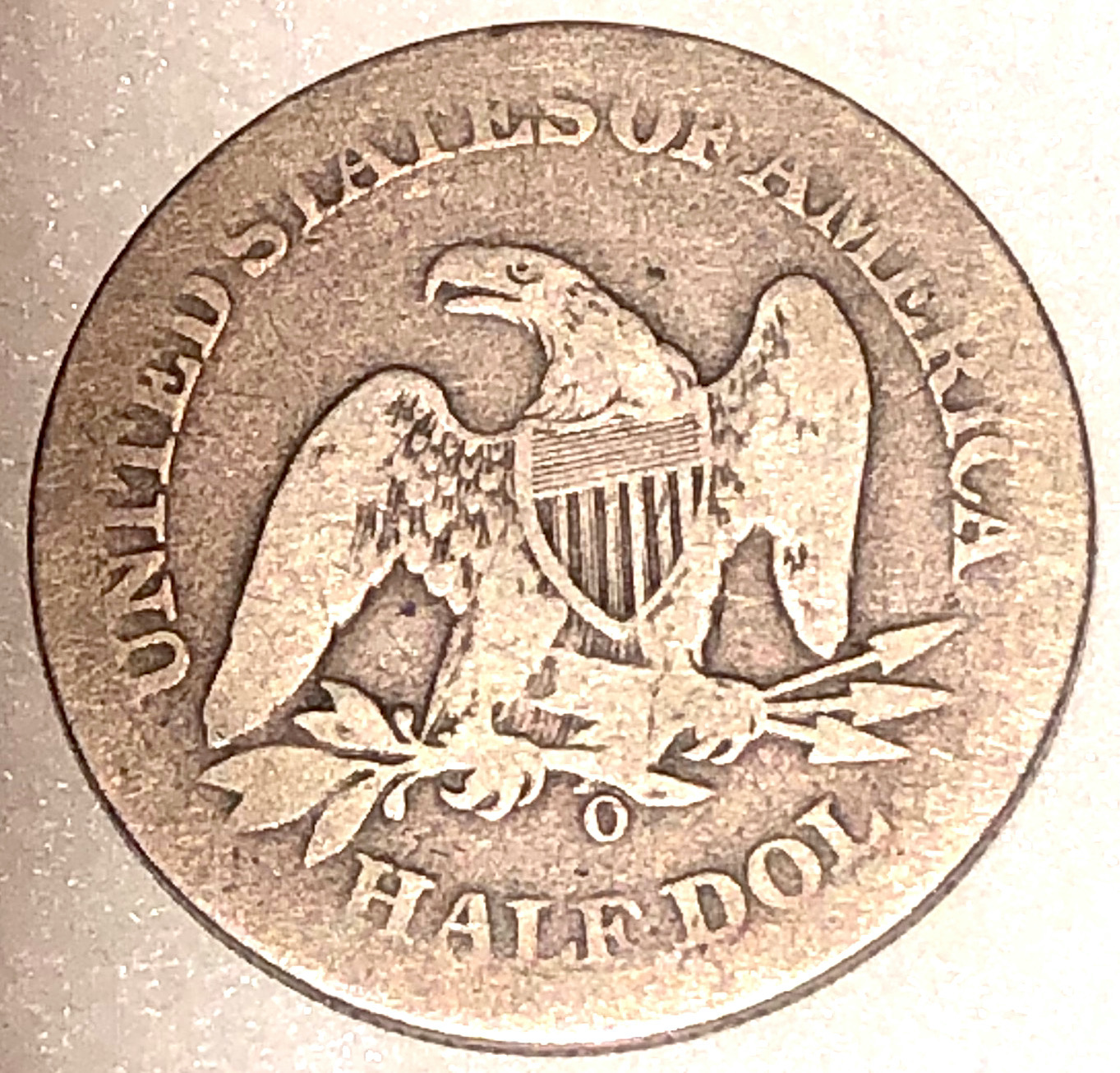

Seated Liberty U.S. Silver Half Dollar Struck at the New Orleans Mint in 1861

SOLD

Seated Liberty U.S. Silver Half Dollar Struck at the New Orleans Mint in 1861 – This rare New Orleans minted, silver half dollar is mint marked “O” for the U.S. Mint in New Orleans. After the Civil War began and prior to the Union capture of New Orleans, in 1862, the newly seceded State of Louisiana, under the auspices of the Confederate government, used the manufacturing capability of the former, Federal Mint in New Orleans, to mint sitting Liberty, silver, half dollars. These coins were almost exact copies of the 1860 Half Dollars. The 1861-O Liberty Seated Half Dollar represents one of the most historically significant issues in US coinage. The 1861-O half dollar was minted under the auspices of the United States of America at the outset of 1861. Following the secession of Louisiana on January 26, 1861, the issue was coined under the authority of the Republic of Louisiana, and finally after Louisiana joined the Confederacy, the issue was minted under the authority of the Confederate States of America (CSA) until suspension of coining operations in April of 1861. The surfaces of this coin are smoothed through years of circulation in commerce.

Secession & Seizure: The Story of the 1861-O Seated Liberty Half Dollar

Posted by Carl Hahn on 31st Jan 2021

The 1861-O Seated Liberty half dollar minted at New Orleans holds a historic place in history as the only US coin to be minted under three separate governments and one of the few coins to become a circulation issue coin for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The year 1861 began one of the most tumultuous times in the history of our nation. Long simmering differences between northern and southern states drawn along lines of states’ rights, slavery and representation had finally reached a crescendo. Southern states began to seceded from the union, initially as independent states and ultimately uniting to form the Confederate States of America. These actions and the ensuing frictions ushered in what was to become the bloodiest war in our nation’s history – the Civil War. The consequences of which played out across all facets of American life, including coinage.

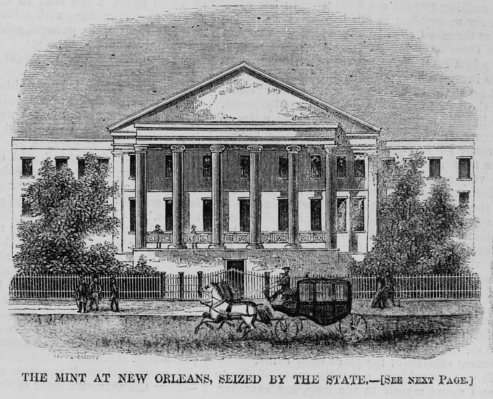

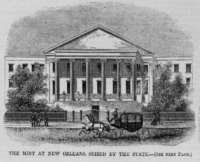

At the outset of 1861, the United States had five mints issuing coinage on behalf of the US government: The primary mint at Philadelphia, and four branch mints located in Charlotte, North Carolina, Dahlonega, Georgia, San Francisco, California, and New Orleans, Louisiana. By the eve of the new year in 1861, it was apparent that sentiment in southern states was turning more aggressively toward dissolution of the union, as South Carolina had already seceded on December 20, 1860. As rumors swirled that more southern states were on the brink of secession, attempts were made by the Treasury Department of the United States to safeguard the reserves of coin and bullion at the branch mints to prevent loss. To that end, the Secretary of the US Treasury, John Adams Dix, issued a draft in the amount of $300,000 to the branch mint in New Orleans in late January of 1861. A.J. Guirot, the Superintendent of the New Orleans Mint received the draft request, but aware of the likely imminent secession of the state of Louisiana, he stalled for time to confer with Louisiana authorities on the draft request. The State of Louisiana formally seceded from the United States on January 26, 1861. Adams & Company express was dispatched to the mint to retrieve the $300,000 draft shortly after the draft request was made. Upon reaching the mint, the express company was turned away by Guirot. As printed in the Evening Star newspaper (Washington, D.C.) on Saturday, February 22, 1861:

“Today, the Treasury Department were notified by Adams & Co.’s express that A.J. Guirot, the Superintendent of the New Orleans mint and Asst. United States Treasurer there, had refused to pay a draft of the department for $300,000, placed in their hands for transfer to Philadelphia. It is supposed at the Department that in these seizures a million of the money of the Government have fallen into the hands of revolutionists. Guirot’s answer, on the presentation of the draft was that “the money in his custody was no longer the property of the United States, but of the Republic of Louisiana.””

The Hillsborough Recorder (Hillsborough, North Carolina), in the Wednesday, February 20, 1861 edition, reported:

“The authorities of Louisiana found $419,311.52 in the United States Mint and $483,983.98 in the subtreasury. Of the sum in the mint, $24,992.68 belonged to individual depositors.”

While modest by modern standards, this represented a significant sum of money in 1861. In 1861, the entire US government budget was only $80.2 million. The seizure of the New Orleans mint and the associated bullion and coinage represented a windfall for Louisiana and upon joining the Confederacy on March 21, 1861 the remaining assets were transferred to the Confederacy. The seizure of the mint, however, did not stop the issuance of coinage there. The New Orleans mint continued to strike coins using the US government dies for the remainder of the year, first under the Republic of Louisiana and later under the Confederacy.

Through an exhaustive evaluation of 1861-O half dollars, Randy Wiley and Bill Bugert have identified fifteen die marriages for 1861-O coins and assigned a coining authority and estimated population to each. By their estimations, there are approximately 55,000 half dollars minted under the authority of the US Mint in January of 1861. The Republic of Louisiana minted approximately 1,240,000 half dollars between January 26 and March 21 and the Confederate States of America coined an additional 962,633 half dollars thereafter. Likely the coinage of the half dollar continued at the New Orleans mint until the reserve of bullion was exhausted.

The Confederate States had undertaken the commission of a new half dollar design to be minted at New Orleans, but the design would never see production. Originally commissioned by C.G. Memminger, the Secretary of the Confederate Treasury, only four known examples were ever coined and none reached circulation. The Confederate mint at New Orleans was closed on April 30, 1861 and did not reopen during the war. The independence of New Orleans from US federal governance and the hope for coinage issued by the Confederacy was short lived. Union forces, led by Admiral David Farragut, entered the waters of New Orleans on April 25, 1862 and promptly overwhelmed the defending Confederate fleet. The commanding Confederate General in New Orleans, General Mansfield Lovell, withdrew his forces to prevent destruction of the city by Union bombardment. The defending forces at Forts Jackson and St. Phillip surrendered on April 29, 1862 allowing Union forces to enter the city. The strategic port of New Orleans would remain under Union occupation until the end of the Civil War, and with it vital control of the Mississippi River and a key supply link of the Confederacy.

Then I did more reading on the history of the mint and the half dollars produced that year. From the end of January through February, the state of Louisiana took control of the mint after seceeding from the Union. After February the CSA took control of the mint, and produced coinage through April. There are several die pairs and die marriages associated with the 1861 half dollars, some of which have been attributed to the CSA produced coins. (Cited from: https://www.cointalk.com/threads/1861-o-half-dollar-history-and-my-purchase-of-one.203091/)

Civil War and recommissioning, 1861–1879

Secession and Confederate seizure

The New Orleans Mint operated continuously from 1838 until January 26, 1861, when Louisiana seceded from the United States. On January 29, the Secession Convention reconvened at New Orleans (it had earlier met in Baton Rouge) and passed an ordinance that allowed Federal employees to remain in their posts, but as employees of the state of Louisiana. On February 5, 1861, during the proceedings of the Convention of the State of Louisiana in New Orleans, the committee appointed by the Convention to take an inventory on February 1, 1861, of public property in the hands of the officers of ‘the late’ Federal government reported that the Sub-Treasurer’s vault at the mint contained $483,983 in gold and silver coins. The National Archives records in Rockville, Maryland, indicate the $483,983 consisted of $308,771 in gold coins and $175,212.08 in silver coins. The only gold coin produced in January, 1861 was the $20 gold double-eagle. This means 15,438 $20 gold coins were minted by the New Orleans Mint during January, 1861. Mint coinage records for the $20 1861-O gold double-eagle indicate only 5,000 $20 gold pieces were minted by the Federal Government in January, 1861. This discrepancy is explained in a Numismatist Journal article.

In March 1861, Louisiana ratified the Constitution of the Confederate States and the Confederate government retained all the mint officers. They used it briefly as their own coinage facility. The Confederates struck 962,633 of the 2,532,633 New Orleans half-dollar coins dated 1861. Research suggests that 1861-O half dollars bearing a bisected date die crack (“WB-103”) and 1861-O half-dollars with a “speared olive bud” anomaly (“WB-104”) on the reverse had been minted under authority of the Confederacy. Confederate officials designed alternate reverse dies which they used to strike their own half-dollars in New Orleans (see image). The exact number of the half-dollar coins struck by the Confederate mint with the alternate reverse is unknown; but only four are known to exist today. One of them, which was sold at auction for a large sum, had once been owned by Jefferson Davis, the only President of the C.S.A.

Confederate minting operations continued from April 1 until the bullion ran out later that month. The staff remained on duty until May 31, 1861. After that the mint was used for quartering Confederate troops, until it was recaptured along with the rest of the city the following year, largely by Union naval forces under the command of Admiral David Farragut.

Occupation by Union forces

For many Southern sympathizers, the Mint soon became a symbol of their hatred for the Union occupation. After U.S. Marines under Farragut had raised the U.S. flag on the roof of the Mint in April 1862, a professional steamboat gambler named William Bruce Mumford ascended the roof and tore the flag down. He ripped the banner into shreds, and defiantly stuffed pieces of it into his shirt to wear as souvenirs. Union General Benjamin Franklin Butler, the military governor of New Orleans (who was soon to be derisively nicknamed “Spoons” for allegedly pocketing the silverware of New Orleans citizens) arrested Mumford for treason against the United States and ordered Mumford executed in retaliation. And so, Mumford was hanged from a flagstaff projecting horizontally from the building on June 7, 1862. Mumford’s hanging made national headlines. Jefferson Davis demanded that Butler immediately be executed if captured. The event stuck in the minds of many New Orleanians: eleven years later, in 1873, a visitor to the city named Edward King mentioned it in his description of the structure