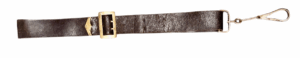

Civil War Pattern 1861 Cartridge Box Containing Unopened Pack of St. Louis Arsenal Cartridges and a Partially Opened Pack of St. Louis Arsenal Cartridges

SOLD

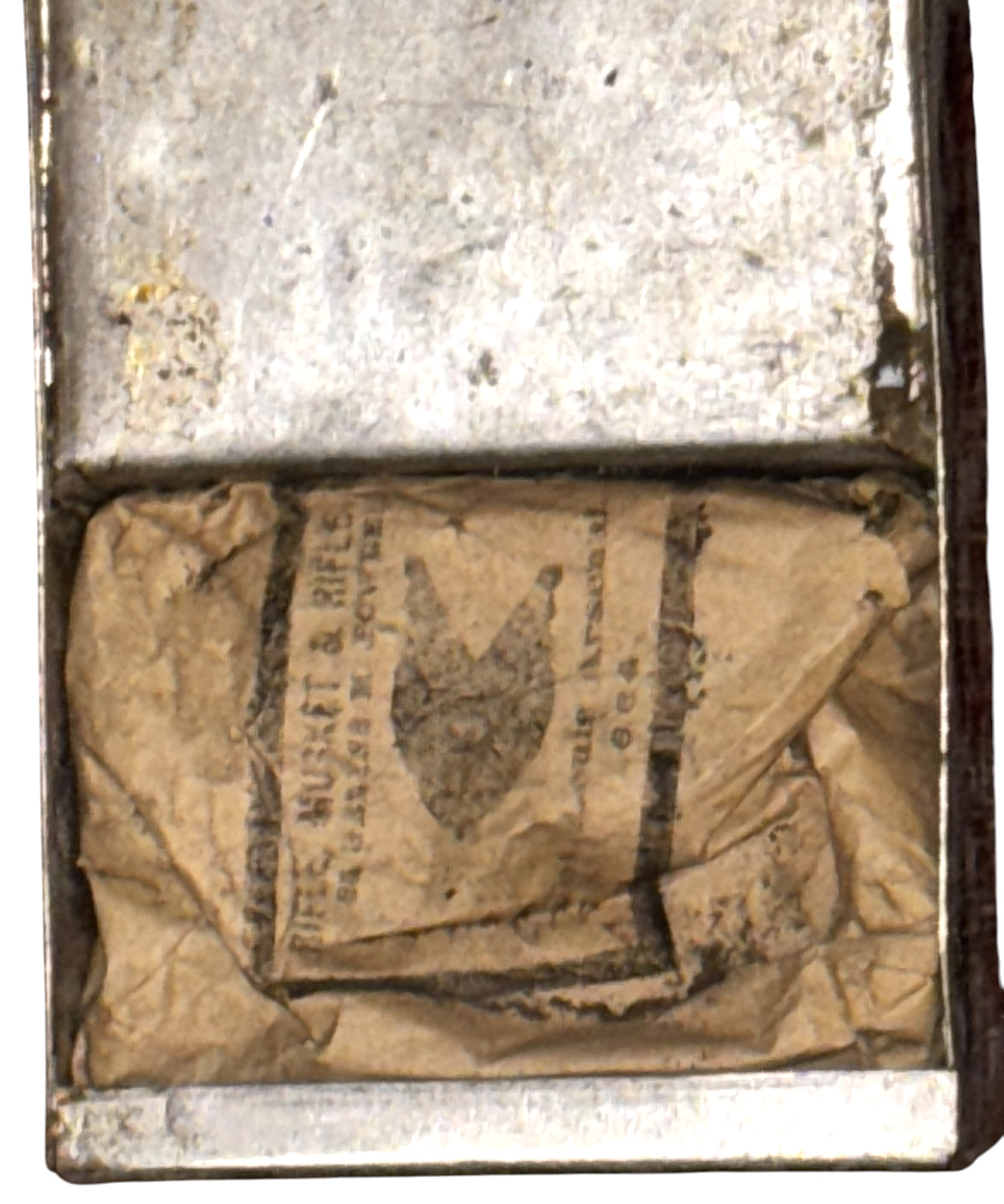

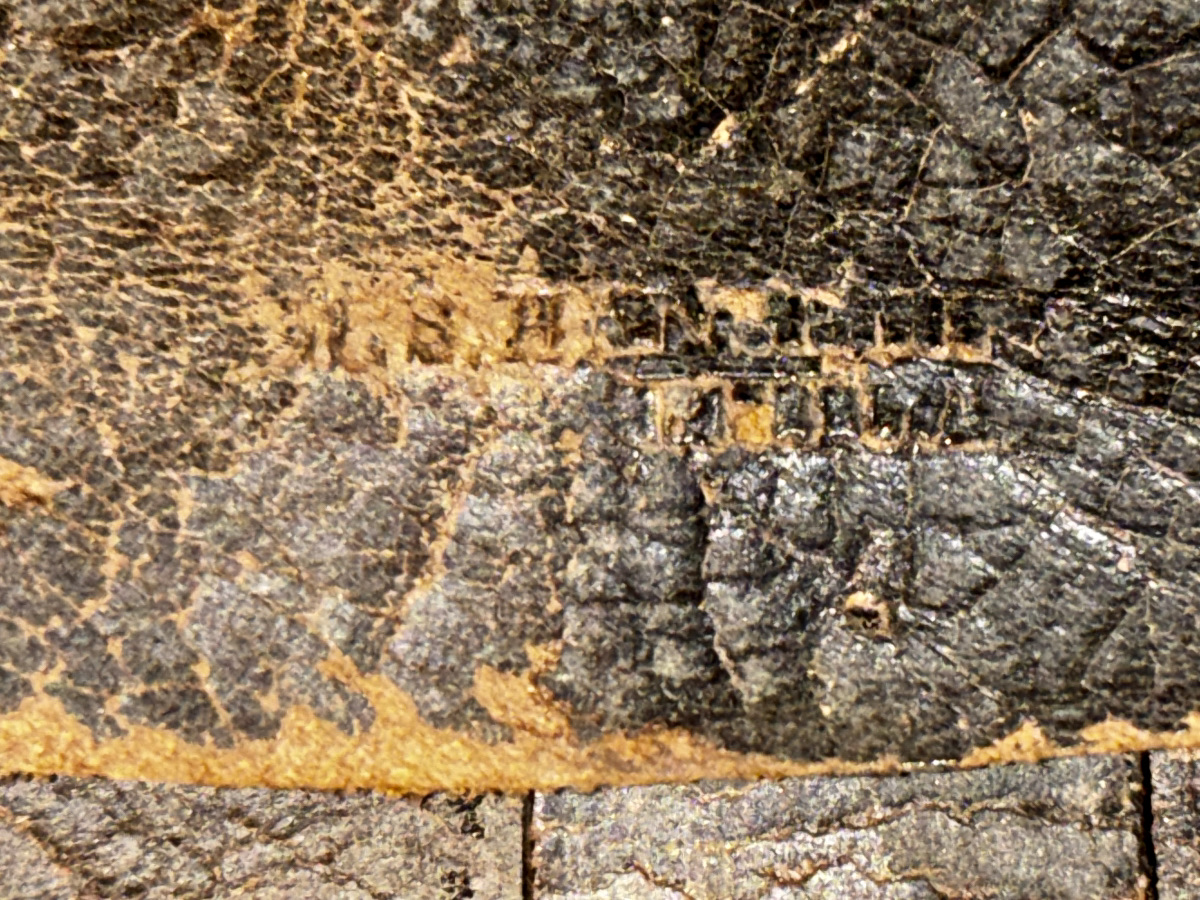

Civil War Pattern 1861 Cartridge Box Containing Unopened Pack of St. Louis Arsenal Cartridges and a Partially Opened Pack of St. Louis Arsenal Cartridges – We recently obtained this Pattern of 1861 US Issue Cartridge Box from a long time collector; still contained in one of the box’s tins is an unopened paper, twine-bound package of .58 caliber, musket cartridges – the package is labeled as being an 1864 product of the St. Louis, Missouri Arsenal. In the second tin, is the paper wrapping, also marked as an 1864 product of the St. Louis Arsenal, with several loose, still paper wrapped .58 cal. musket rounds, as well as several loose .58 cal. bullets, with empty paper wrappers and some percussion caps. We have chosen to leave the full, unbroken pack and the now empty wrapper in their respective tins. The cartridge box remains in overall very good condition, with some “alligatoring” to the leather, but no flaking or chipping. The original box plate is affixed to the cover with old string; we will replace that string with original leather thongs. There is a maker’s stamping on the interior cover, but we have not been able to discern what that mark says. This is a remarkable find, with rounds, as issued, still located in their cartridge box tins. Each of the paper wrappers are labeled as follows:

“RIFLE MUSKET & RIFLE

84 GRAINS M POWDER

St. Louis Arsenal

1864”

Between the descriptor label and the arsenal name, is a cross-sectional view of a .58 cal. bullet.

St. Louis Arsenal History

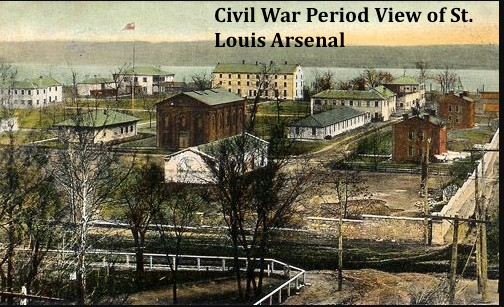

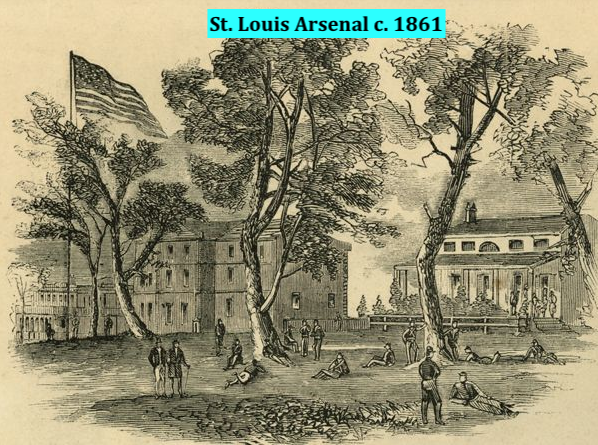

The St. Louis, Missouri Arsenal is a large complex of military weapons and ammunition storage buildings owned by the United States. The arsenal, which was built in 1827, is still utilized today. In 1825, the arsenal was located at Fort Belle Fontaine, some 15 miles north of St. Louis, Missouri, but the old fort and its small arsenal were falling into disrepair. Additionally, the War Department felt it needed a more extensive facility and began planning to build a new one.

Lieutenant Martin Thomas selected A new site on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. The 37-acre site was advantageous for its strategic view, access to the river, and proximity to the main area military base — Jefferson Barracks. In 1827, the first building on the new arsenal grounds was completed, but it would be a year before storing the ammunition. In the meantime, Fort Belle Fontaine continued to supply ammunition and military supplies to troops operating in the Louisiana Territory until June 1828.

Fort Belle Fontaine was abandoned when the St. Louis Arsenal began storing ammunition and supplies. The new St. Louis Arsenal grew to house a large three-story brick building, an armory, an ammunition plant, and several wagon repair shops. By 1840, 22 separate buildings had been erected, and a garrison of 30 ordnance soldiers manned the site, along with 30 civilian employees, who assembled finished weapons and artillery.

When the Mexican-American War erupted in 1846, the arsenal was busy producing small arms, ammunition, and artillery, increasing its civilian workers to about 500 men. During the war, the arsenal had 19,500 artillery rounds, 8.4 million small arms cartridges, 13.7 million musket balls, 4.7 million rifle balls, 17 field cannons with full attachments, 15,700 stands of small arms, 4,600 edged weapons, and much more. When the war was over, the civilian staff was reduced to about 30, and the arsenal was relatively quiet for about a decade until the Utah War began in 1857. Civilian staff was once again increased, this time to about 100 civilians.

Before the Civil War, several members of Congress anticipated secession. They demanded that their quota of arms and ammunition be shipped from the St. Louis Arsenal to state armories and arsenals. In December 1860, President James Buchanan’s Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, a Virginian, was accused of aiding in transferring arms to southern states. He quickly resigned from his post and returned to Virginia. Afterward, an investigation was conducted into his involvement, where it was found that he had bolstered the Federal arsenals in some Southern states by over 115,000 muskets and rifles in late 1859. He had also ordered heavy artillery to be shipped to the Federal forts in Galveston Harbor, Texas, and Fort Massachusetts in Mississippi. Though he was officially cleared of any wrongdoing, many continued to suspect that his involvement had helped arm the Confederate States of America in preparation for the Civil War.

By early 1861, the Civil War was looming, and the states were choosing sides. Missouri was caught in the middle as most of its residents supported slavery. Despite this, the Missouri Constitutional Convention of March 1861 voted to stay with the Union but refused to supply men or weapons to either side if war broke out. This resulted in a war within its borders between the U.S. Army and Missouri citizens, and the St. Louis Arsenal would become a primary target.

In March 1861, General Nathaniel Lyon arrived in St. Louis to command Company D of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. At that time, Missouri Governor Claiborne F. Jackson was a strong Southern sympathizer, as were many state legislators. Lyon was accurately concerned that Jackson might try to seize the federal arsenal in St. Louis if the state seceded. The Union had insufficient defensive forces to prevent the seizure.

One of Lyon’s first objectives was to strengthen the arsenal defenses, but his superiors, including Brigadier General William S. Harney of the Department of the West, opposed him. However, Lyon soon requested the aid of General Francis P. Blair, who agreed that southern leaders might try to carry neutral Missouri into the Confederate movement. Lyon was soon named commander of the arsenal, and General Blair formed a secret paramilitary group of 1,000 men called the Wide Awakes.

On April 20, 1861, a pro-Confederate mob at Liberty, Missouri, seized the only other arsenal in the state — the Liberty Arsenal. The Southern sympathizers captured about 1000 muskets, four brass field pieces, and a small amount of ammunition. It was the first civilian Civil War hostility against the Federal government in the state.

In response, Lyon armed the Wide Awake units and, on April 29, secretly sent all but 10,000 rifles and muskets to Alton, Illinois. A few days later, on May 10, he directed the Missouri volunteer regiments and the 2nd U.S. Infantry to capture a force of Missouri State Guards stationed at Camp Jackson in the suburbs of St Louis to seize the arsenal. Federal troops surrounded and captured the camp, forcing its surrender. Though Lyon’s actions gave the Union a decisive initial advantage in Missouri, it also inflamed secessionist sentiments.

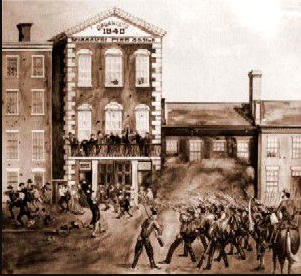

After capturing the force of Missouri State Guards, Lyon marched them through the streets of St. Louis to the Arsenal. This long march was widely viewed as public humiliation for the state forces and angered citizens who watched the commotion. Before long, riots broke out as Missouri citizens hurled rocks, paving stones, and insults at Lyon’s troops. When a pistol was fired into their ranks, fatally wounding one Union soldier, the Federals fired into the crowd, killing some 20 people, some women, and children, and wounding as many as 50 more. Known as the “St. Louis Massacre,” the incident sparked several days of rioting that was only subdued with the installation of martial law and the arrival of Federal Regulars. The highly-publicized affair further increased the tension in the border state of Missouri.

Later, General Nathaniel Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, 1861. The St. Louis Arsenal remained in Federal hands throughout the Civil War and, with St. Louis firmly in Union control, provided substantial quantities of war materiel to the armies in the Western Theater.

When the Civil War was over, the arsenal again became relatively quiet. In March 1869, ten acres of arsenal grounds were given to the City of St. Louis to create Lyon Park, named for General Nathaniel Lyon. Two years later, in 1871, it was determined that the ammunition could be better secured at Jefferson Barracks, and the supplies were transferred, though the U.S. Army retained the arsenal grounds.

Old barracks building at the St. Louis Arsenal in Missouri.

Later, the arsenal complex was transferred to the United States Air Force and the Department of Defense. Today, it is an active military reservation, housing a significant branch of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

Most of the St. Louis Arsenal and its grounds are closed to the public today. Visitors and cameras are not allowed inside the complex, but you can still visit a part of the arsenal that is open to the public. Nearby is Lyon Park, located near the intersection of South Broadway and Arsenal Streets.

The St. Louis Arsenal is a large complex of federal military weapons and ammunition storage buildings operated by the United States Air Force in St. Louis, Missouri. During the American Civil War, the St. Louis arsenal’s contents were transferred to Illinois by Union Captain Nathaniel Lyon, an act that helped fuel tension between secessionists and those citizens loyal to the Federal government.

Origin and early years of service

In 1827, the United States War Department decided to replace a 22-year-old arsenal, Fort Belle Fontaine (located 15 miles (24 km) north of St. Louis on the bluffs above the Missouri River) with a larger facility to meet the needs of the rapidly growing military forces in the West. Lt. Martin Thomas selected a 37-acre (150,000 m2) tract of land on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River and procured the land for the new arsenal. It was close to the main military base, Jefferson Barracks, and had easy access to the city and the river. By 1840, 22 separate buildings had been erected, and a garrison of 30 ordnance soldiers manned the site, along with 30 civilian employees, who assembled finished weapons and artillery from parts supplied by private contractors and armories. In its original configuration it included Arsenal Island in the Mississippi River. The island has since disappeared.

When the Mexican–American War erupted, the demand for small arms, ammunition, and artillery substantially increased. At its peak during the war years, the St. Louis Arsenal employed over 500 civilian workers. During the two years of war, the arsenal produced 19,500 artillery rounds, 8.4 million small arms cartridges, 13.7 million musket balls, 4.7 million rifle balls, 17 field cannon with full attachments, 15,700 stand of small arms, 4,600 edged weapons, and much more.[1] Production was curtailed following the cessation of the war, although the arsenal workers (back to their normal complement of 30) did spend considerable time refurbishing and reconditioning surplus arms returned from the war.

Another flurry of activity accompanied the Utah War in 1857–58, when President James Buchanan ordered an expedition of Federal troops to suppress the Mormons. Employment exceeded 100 workers, and the arsenal provided much of the weaponry for William S. Harney‘s forces.

Civil War

Anticipating secession, a number of Southern states asked for their quota of arms and ammunitions to be shipped from the St. Louis Arsenal to state armories and arsenals. Buchanan’s Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, a Virginian, was accused of aiding in this transfer of arms and resigned his post in December 1860 to return to Virginia. An investigation cleared him, but many suspected that his involvement had helped arm the Confederate States of America and prepare it for war in advance of actual ordinances of secession from the individual states.

The armory, which was used for assembling weapons rather than manufacturing them, had the biggest collection of rifles and muskets of any of the slave states and was fourth after Massachusetts, District of Columbia, New York and California in total number of muskets and rifles (38,141). It also had the third largest arms and munitions manufactury in the Federal system (behind Springfield, MA and Harper’s Ferry, VA).

Despite its enormous strategic importance, it had traditionally been lightly guarded, with a staff of forty military and civilian personnel.

In March 1861 the Missouri Constitutional Convention of 1861 voted 98 to 1 to stay in the Union but not supply weapons or men to either side if war broke out. The security of such a large munitions depot became an immediate flash point.

On April 20, 1861 a pro-Confederate mob at Liberty, Missouri, seized the only other arsenal in the state, the Liberty Arsenal, and made off with about 1,000 rifles and muskets.

On April 23, Brigadier General Harney departed for Washington, leaving Captain Lyon in temporary command of the Western Department and the Arsenal.[clarification needed] Lyon immediately began enlisting Missouri Unionist Volunteers into Federal service. This action had been ordered over a week before by Secretary of War Simon Cameron, but blocked by General Harney’s refusal to execute his orders.

Cameron, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, and midwestern Unionists continued to be concerned for the safety of the over 30,000 weapons at the Arsenal. During the evening of April 29, on orders from Secretary Cameron, Captain Nathaniel Lyon transported 21,000 rifles and muskets to Alton, Illinois, via steamer.

Around May 1, Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson, who had favored the South but had publicly pledged to uphold Missouri neutrality (at least until open hostilities between the Federal Government and the CSA), called out the Missouri Volunteer Militia for “maneuvers” about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) northwest of the arsenal at Lindell’s Grove (now the campus of St. Louis University), then outside the city of St. Louis, in what has been called “Camp Jackson.”

Lyon suspected the maneuvers were a thinly veiled attempt to seize the arsenal (suspicions furthered by the discovery that Jefferson Davis had sent artillery to the maneuvers).

On May 10, Lyon surrounded the militia, which surrendered. While marching the Militiamen through the streets of St. Louis back to the arsenal, a riot erupted. The troops opened fire on the crowd, killing 28 and wounding 90 civilians outright, and then killing another seven as the night progressed in what is called the Camp Jackson Affair.[2]

On May 11, the Missouri General Assembly approved a measure to create the Missouri State Guard to “resist invasion” (by federal forces) and “suppress rebellion” (by Missouri Unionists enrolled in Federal service), with Sterling Price as its major general.

On May 12, Price and William S. Harney signed the Price-Harney Truce, which pledged that the state and federal forces would maintain order in the parts of the state they controlled; protect the rights of all persons in their zones of control; and avoid any provocative acts. Price promised Harney that he would hold the state of the Union, and if Confederate forces entered, he would fight them.

While MG Price’s statement was probably simply a deception to buy time, it caused consternation in the Confederate capitol at Richmond. At that moment, envoys secretly dispatched by Governor Jackson, with Price’s knowledge, were asking Confederate President Jefferson Davis to order an invasion to “liberate” Missouri. They had informed Davis that the Missouri State Guard would fight alongside the Confederate troops and drive the Federal forces from the state.

On May 30, Harney was relieved of command by Abraham Lincoln after demands by Missouri Unionists who felt he was allowing Governor Jackson and General Price to build a secessionist army which would eventually march on, and capture, St. Louis, the main Unionist stronghold in the state.

On June 11, Lyon and Jackson met one last time, at the Planter’s House hotel in St. Louis, to discuss the right of access to the interior of the state for Federal troops. Jackson demanded that Federal forces be limited to metropolitan St. Louis, and that pro-Unionist “Home Guard” companies in St Louis and elsewhere in the state be disbanded. Lyon responded that such a limitation on Federal authority “means war”, and the meeting broke up. Jackson and General Price, who were in St. Louis on a safe conduct, immediately returned to Jefferson City, ordered the railroad bridges burned, and prepared for war. Lyon followed several days later, moving troops and artillery up the Missouri river by steamboat. He captured the state capitol without resistance, and routed the Missouri State Guard at the Battle of Boonville on June 17, 1861. This action secured most of the key strategic parts of the state for the Federal Government, which would control those areas for the rest of the war.

Lyon pursued Governor Jackson and the State Guard down towards the Arkansas border. In August, with the enlistments of his Three Month regiments expiring and facing a combined force of 12,000 Missouri State Guard, Confederates and Arkansas State Troops, Lyon was forced to commit his 5,000 troops to a preemptive attack south of Springfield. The Battle of Wilson’s Creek, often called the “Bull Run of the West” was a confused and bloody one. With a few exceptions, the troops on both sides fought hard and well, and in the end number told. General Lyon was killed leading a charge late in the day, and his successor, Major Schofield, concerned about low ammunition stocks withdrew towards Springfield. The exhausted southern army did not pursue.

A significant tactical victory for the Confederates, in the end Wilson’s Creek was strategically barren. The Arkansas and Confederate troops withdrew across the border, leaving Sterling Price to “liberate” Missouri on his own. While Price went on to win several subsequent engagements, in the end he too had to withdraw, due to a lack of supplies.

The St. Louis Arsenal remained in Federal hands throughout the Civil War, and, with St. Louis firmly in Union control, provided substantial quantities of war materiel to the armies in the Western Theater.

Transfer to Jefferson Barracks

In March 1869, 10 acres (40,000 m2) of the old arsenal grounds were given to the City of St. Louis for the creation of Lyon Park, named for Lyon.

In 1871 the arsenal was transferred to the better secured Jefferson Barracks. That complex was retained by the U.S. Army, with substantial peaks in weaponry and ammunitions storage and dispensing during World Wars I and II. In 1956, it was transferred to the U.S. Air Force.