ShopFebruary 16, 2026

-

Id’d Civil War Buff Officer’s Vest, Gauntlets and Reunion Ribbons of Capt. Maurice Leyden Co. B 3rd NY Cavalry

$2,250Id’d Civil War Buff Officer’s Vest, Gauntlets and Reunion Ribbons of Capt. Maurice Leyden Co. B 3rd NY CavalryFebruary 16, 2026 -

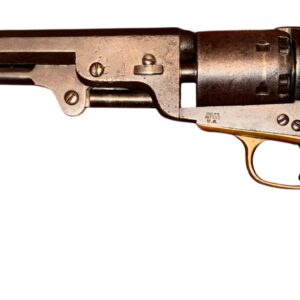

M1851 Martially Marked Colt Navy Revolver

$2,750M1851 Martially Marked Colt Navy RevolverFebruary 15, 2026 -

Civil War Period Shaving Items and Toothbrush

$375Civil War Period Shaving Items and ToothbrushFebruary 4, 2026 -

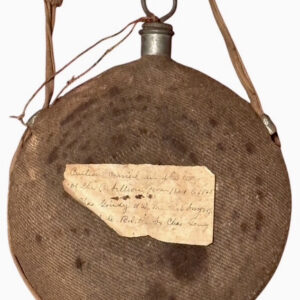

Group of Civil War Period Personal Items

Group of Civil War Period Personal ItemsFebruary 3, 2026 -

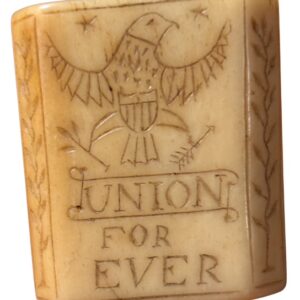

Patriotic Motif Civil War Soldier Carved Bone Cravat or Neckerchief Slide

Patriotic Motif Civil War Soldier Carved Bone Cravat or Neckerchief SlideFebruary 2, 2026 -

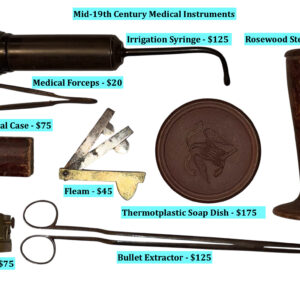

Group of 19th Century, Civil War Period Medical Instruments

Group of 19th Century, Civil War Period Medical InstrumentsFebruary 2, 2026 -

Confederate Side Knife

$650Confederate Side KnifeFebruary 1, 2026 -

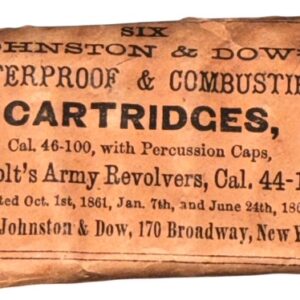

Original Unopened Pack of .44 Caliber Cartridges Made by Johnston & Dow for the M1860 Colt Army Revolver

$425Original Unopened Pack of .44 Caliber Cartridges Made by Johnston & Dow for the M1860 Colt Army RevolverFebruary 1, 2026 -

Civil War Period Starr Percussion Carbine

Civil War Period Starr Percussion CarbineJanuary 30, 2026 -

Civil War Model 1840 Cavalry Officer’s Saber

$2,650Civil War Model 1840 Cavalry Officer’s SaberJanuary 28, 2026 -

Regulation Civil War Issue Eagle Drum by Contractor George Kilbourn

Regulation Civil War Issue Eagle Drum by Contractor George KilbournJanuary 27, 2026 -

Superior Example of a Civil War Folk Art Polychrome Painted and Relief Carved Cane

$3,150Superior Example of a Civil War Folk Art Polychrome Painted and Relief Carved CaneJanuary 26, 2026 -

Civil War U.S. Hospital Department Bottle in Rare Apricot Color

Civil War U.S. Hospital Department Bottle in Rare Apricot ColorJanuary 25, 2026 -

Excavated CS “Egg” Belt Plate

$2,500Excavated CS “Egg” Belt PlateJanuary 24, 2026 -

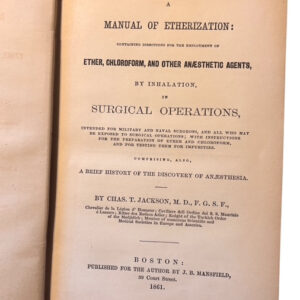

Rare 1st Edition Civil War Medical Book Entitled: A Manual of Etherization : Containing Directions for the Employment of Ether, Chloroform, and Other Anæsthetic Agents, by Inhalation, in Surgical Operations; with Instructions for the Preparation of Ether and Chloroform, and for Testing Them for Impurities. Comprising, also, a Brief History of the Discovery of Anæsthesia – By Charles T. Jackson

$850Rare 1st Edition Civil War Medical Book Entitled: A Manual of Etherization : Containing Directions for the Employment of Ether, Chloroform, and Other Anæsthetic Agents, by Inhalation, in Surgical Operations; with Instructions for the Preparation of Ether and Chloroform, and for Testing Them for Impurities. Comprising, also, a Brief History of the Discovery of Anæsthesia – By Charles T. JacksonJanuary 24, 2026 -

Civil War Pipe Carved by a Soldier in Co. C of the Famed 5th New York Infantry or Duryee’s Zouaves

$1,350Civil War Pipe Carved by a Soldier in Co. C of the Famed 5th New York Infantry or Duryee’s ZouavesJanuary 23, 2026 -

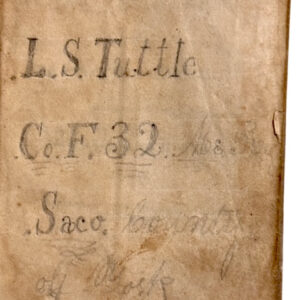

Id’d Civil War Period Pocket Bible – Lewis S. Tuttle Co. F 32nd Maine Infantry – POW and Died at Andersonville

$650Id’d Civil War Period Pocket Bible – Lewis S. Tuttle Co. F 32nd Maine Infantry – POW and Died at AndersonvilleJanuary 22, 2026 -

Pre-War to Civil War Period Cased Surgeon’s Kit by George Tiemann of New York

$3,250Pre-War to Civil War Period Cased Surgeon’s Kit by George Tiemann of New YorkJanuary 22, 2026