Doubly Id’d Rare 7th Regiment Invalid Corps Field Drum – Private John R. Edick Co. K 151st NY Infantry and Private Frederick Bellinger Co. A 56th Pa. Infantry

$1,850

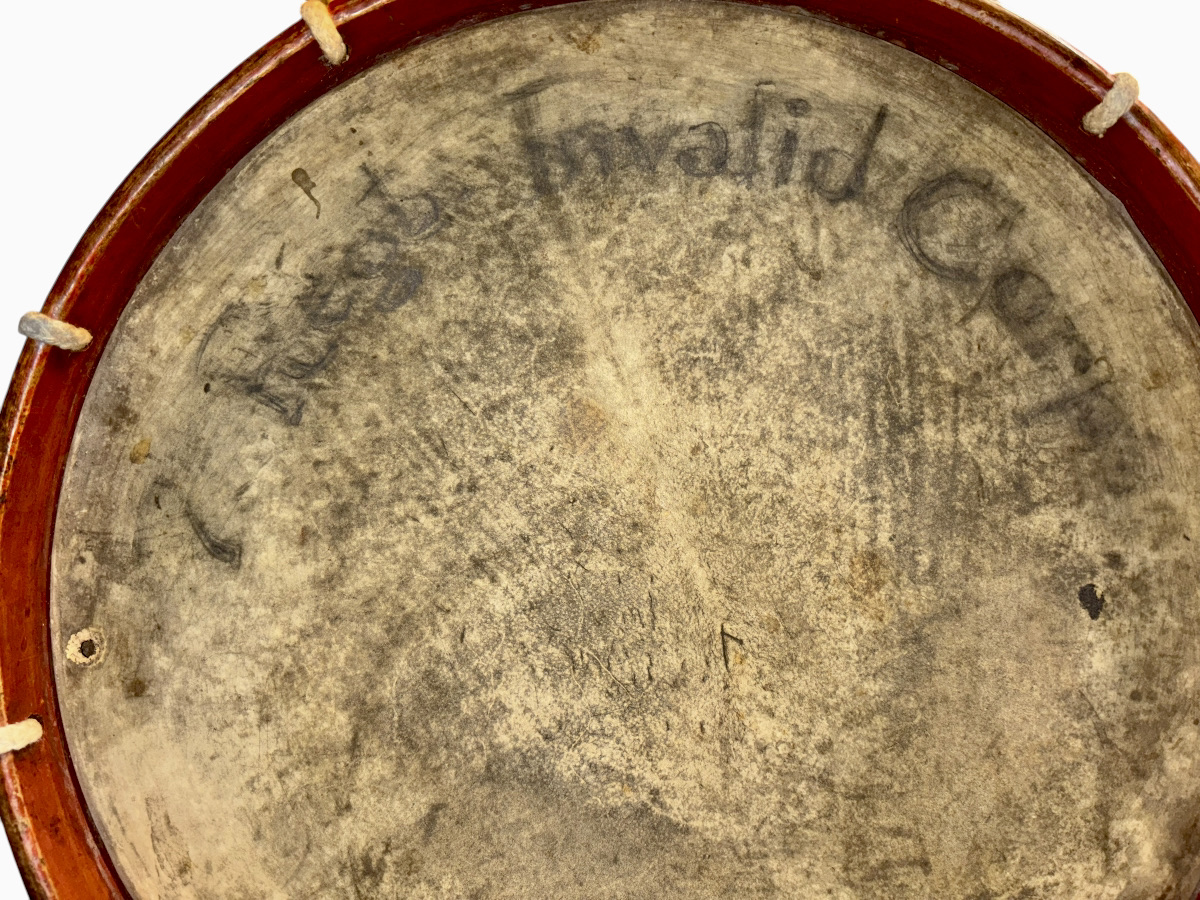

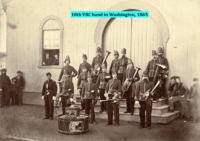

Doubly Id’d Rare 7th Regiment Invalid Corps Field Drum – Private John R. Edick Co. K 151st NY Infantry and Private Frederick Bellinger Co. A 56th Pa. Infantry – We have had several, Civil War field drums, although we have never had an identified drum associated with the Invalid Corps. The Invalid Corps was organized under authority of General Order No. 105, U.S. War Department, dated April 28, 1863. The Invalid Corps was created to make suitable use in a military or semi-military capacity of soldiers who had been rendered unfit for active field service due to wounds or disease contracted in line of duty, but were still fit for garrison or other light duty, and were, in the opinion of their commanding officers, meritorious and deserving. General Order No. 111, dated March 18, 1864 substituted the designation “Veteran Reserve Corps” for that of “Invalid Corps” to provide more respect for the members, as the same initials “I.C.” were stamped on condemned property meaning, “Inspected-Condemned”. The Invalid Corps and Veteran Reserve Corps or VRC, both maintained bands, as indicated by several period images of corps bands. This drum, which remains in excellent condition, has clearly stenciled on the upper or batter head of the drum:

“7 Regt Invalid Corps”

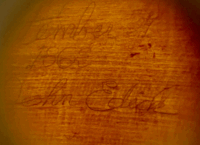

Additionally, these other inscriptions are handwritten on the drum:

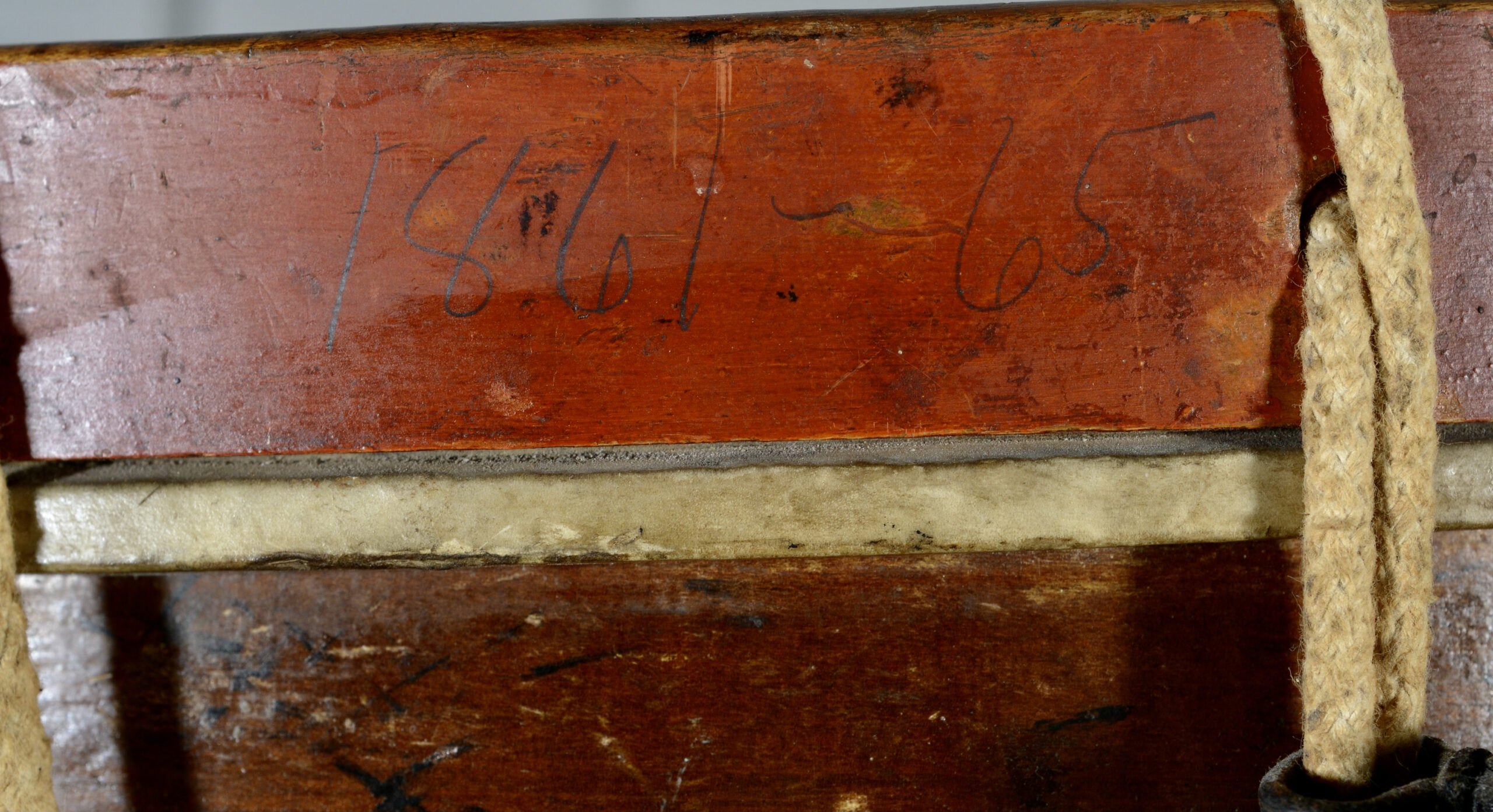

- Handwritten in pencil on the batter head rim:

“Civil War 1861- 65”

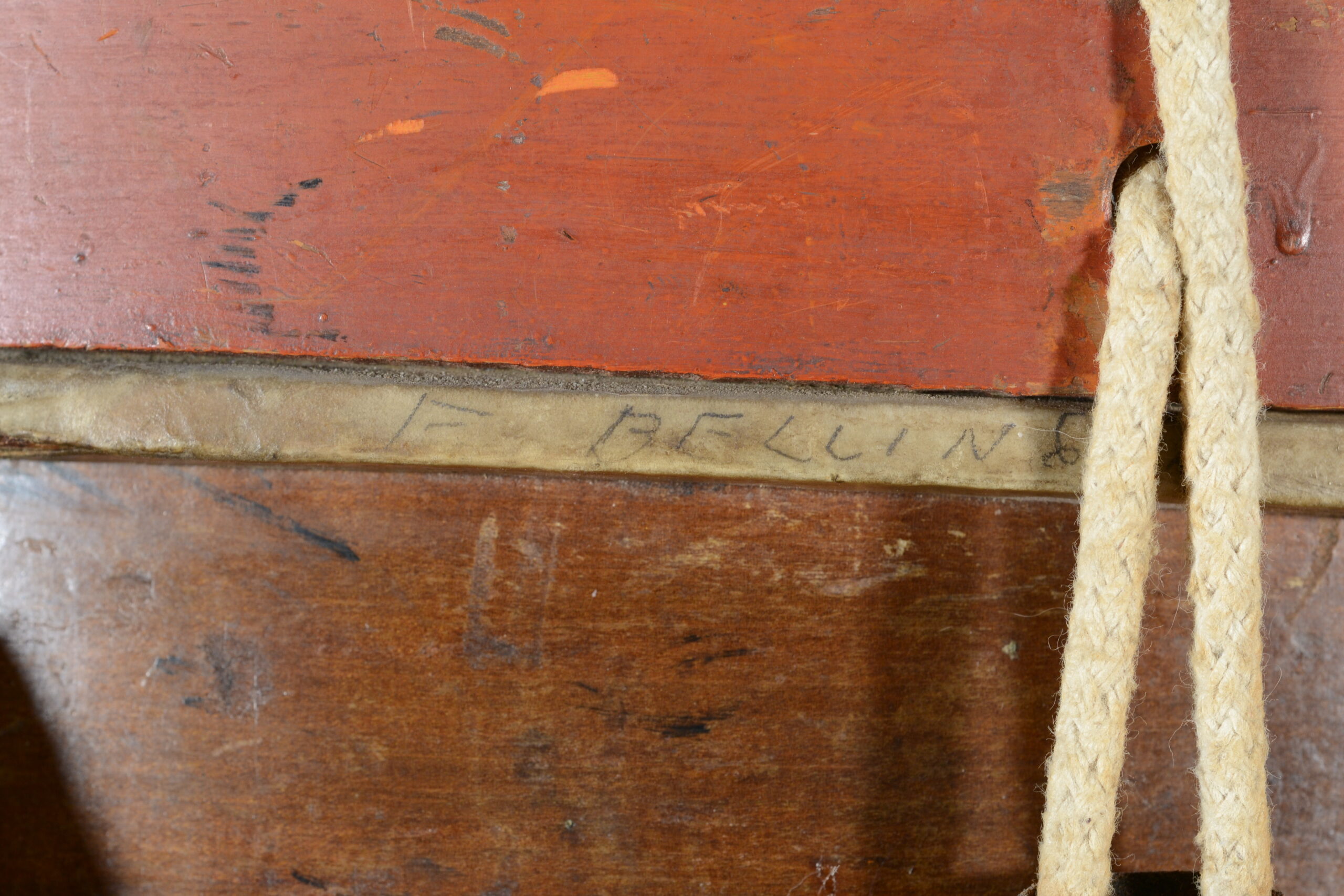

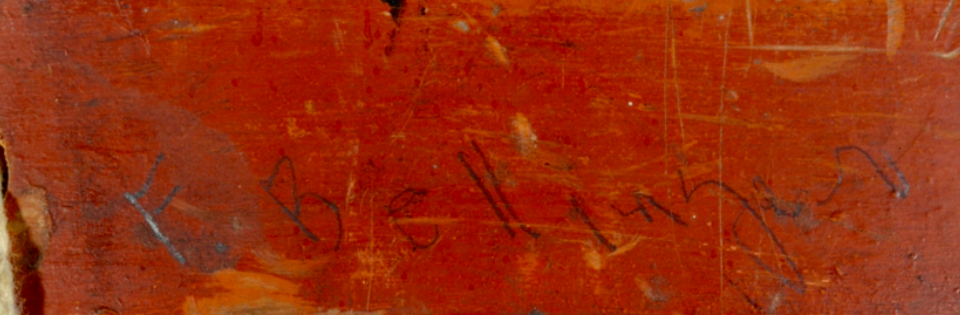

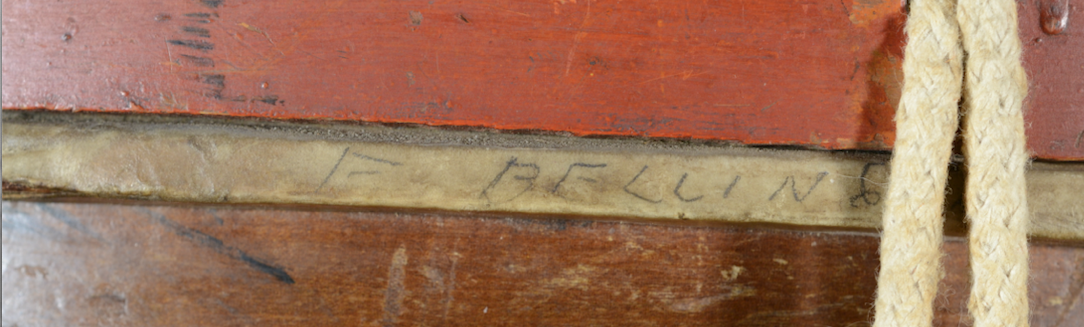

- Handwritten in pencil on the batter head rim and on the drumhead stretched on the lower rim of the drum:

- “Frederick Bellinger

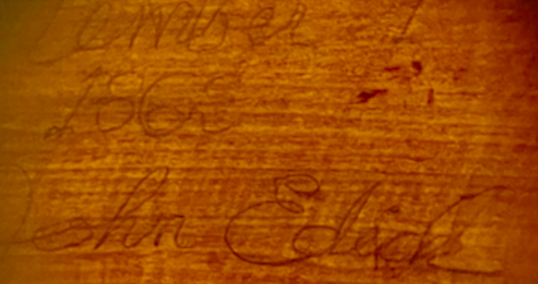

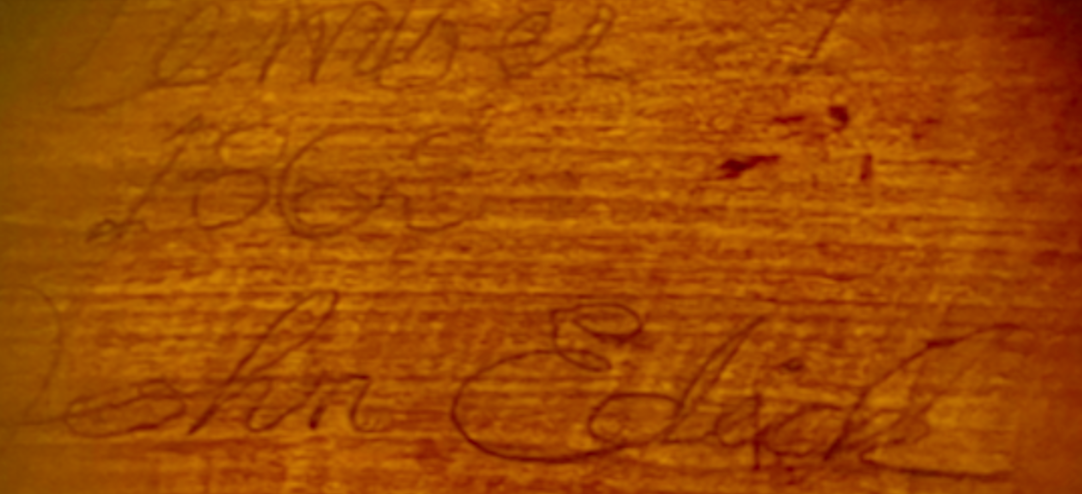

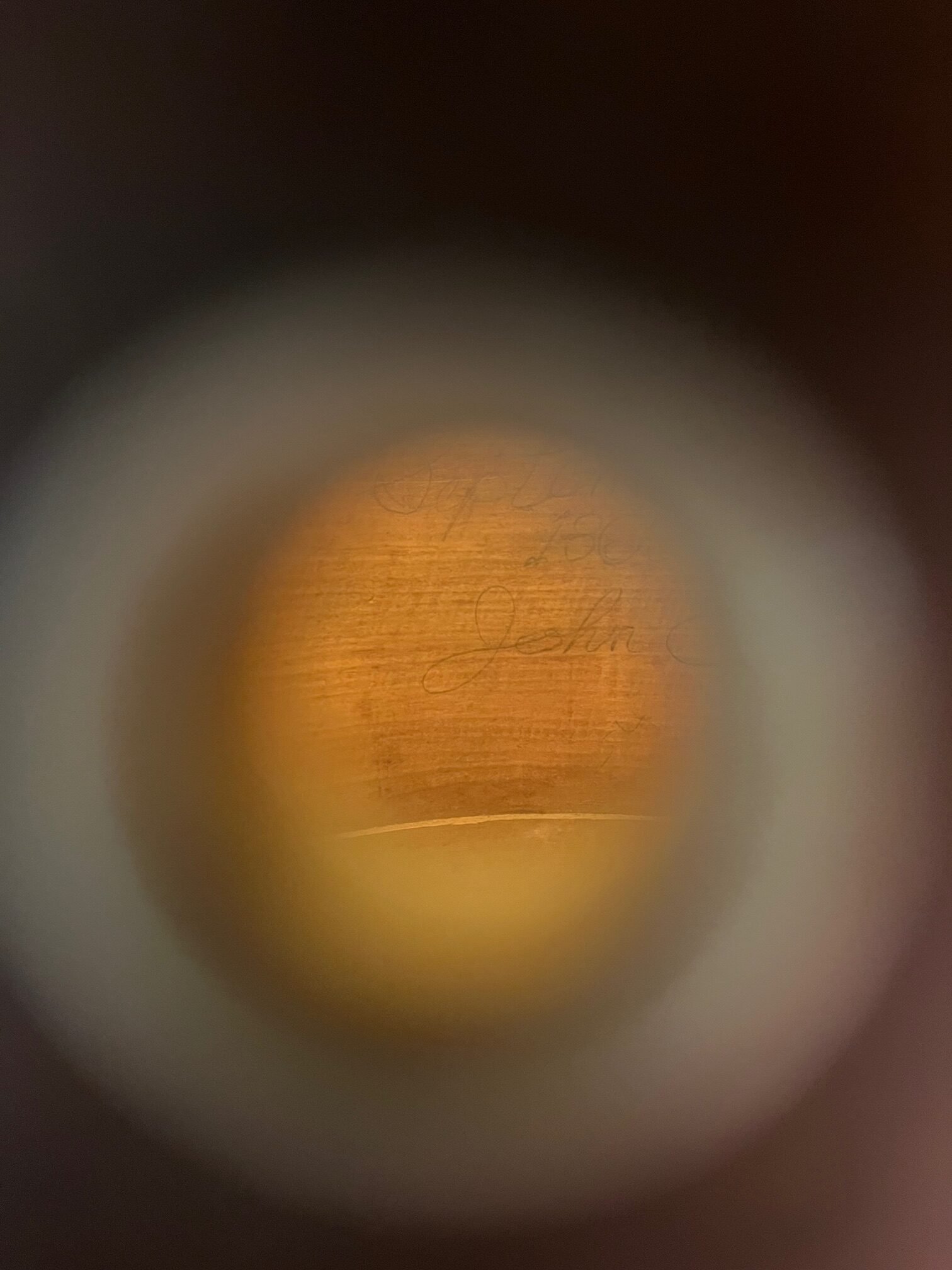

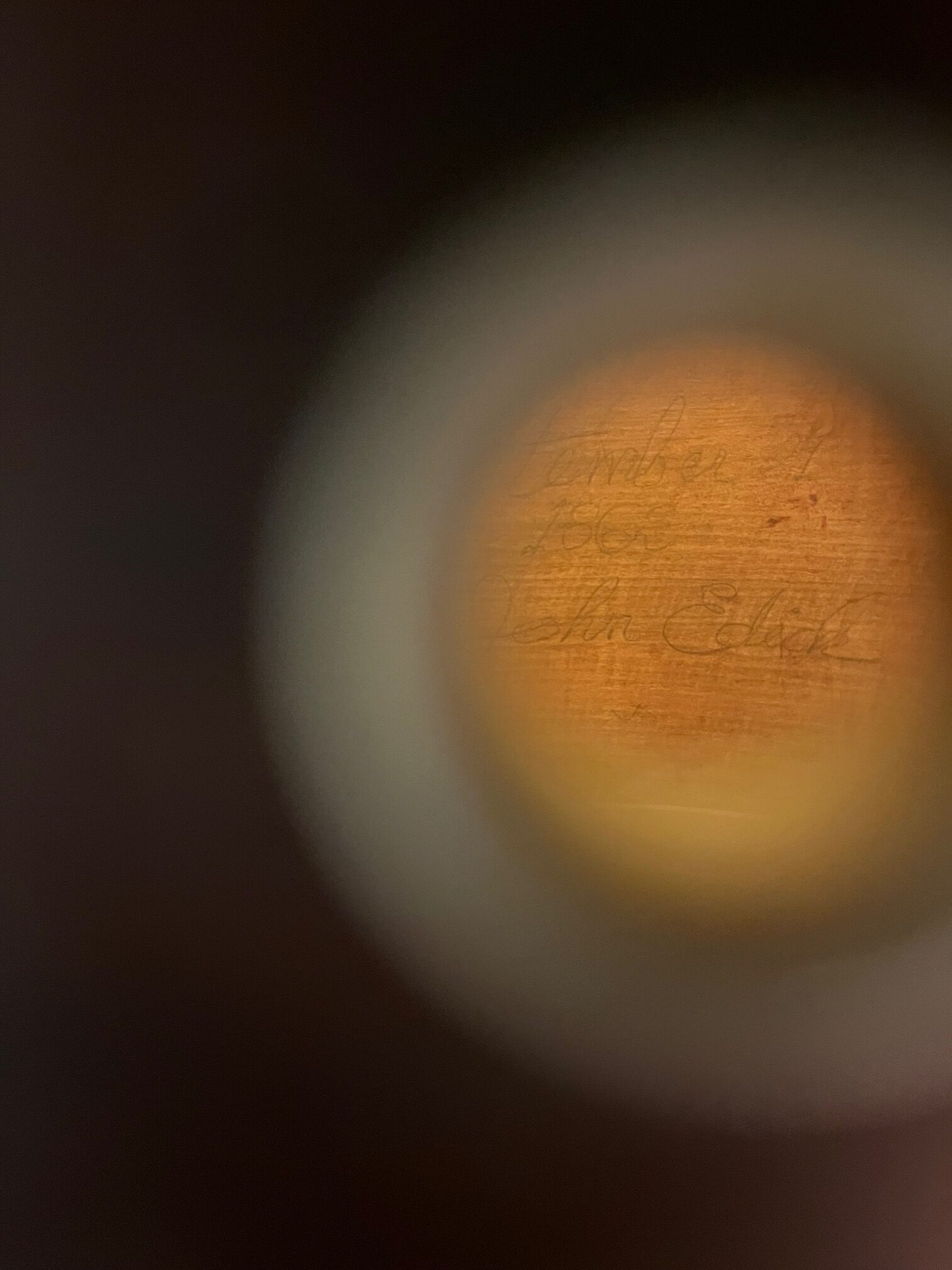

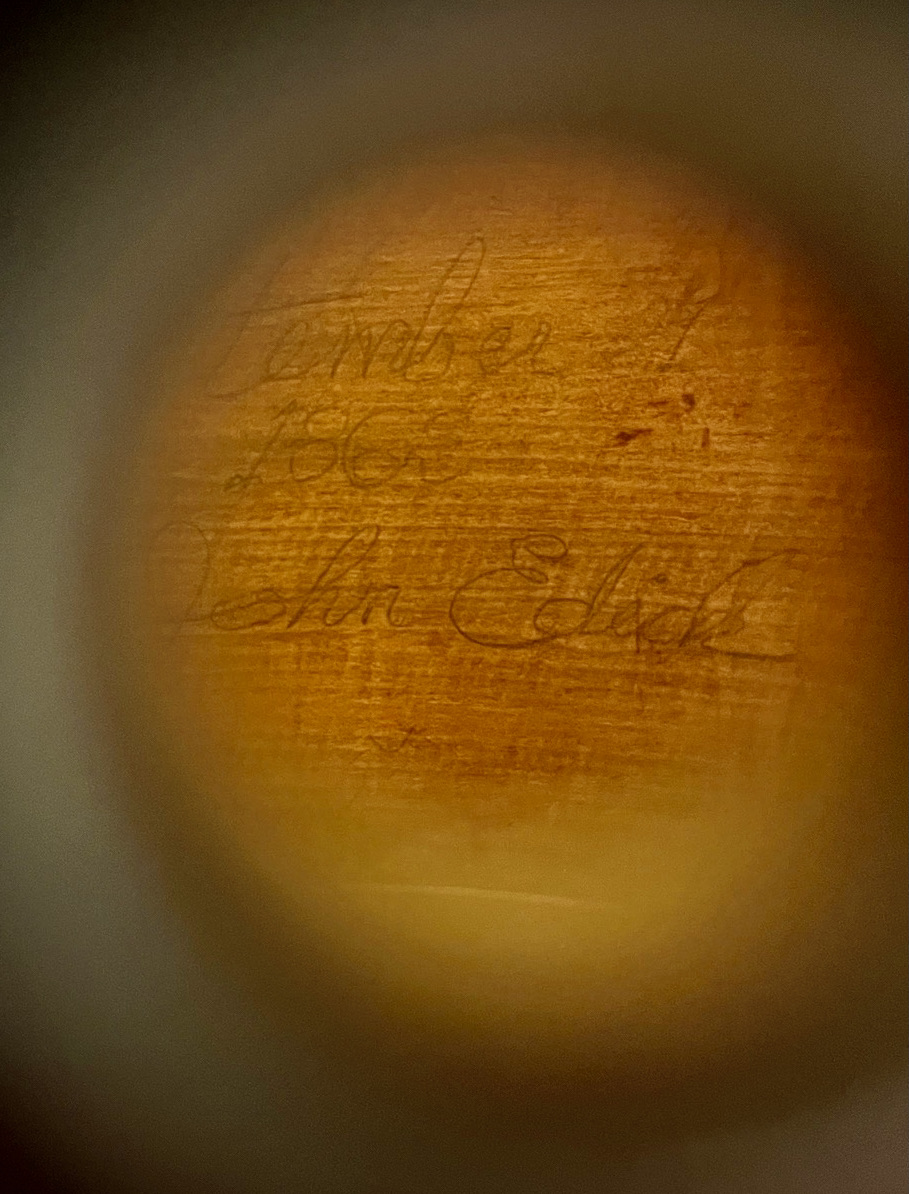

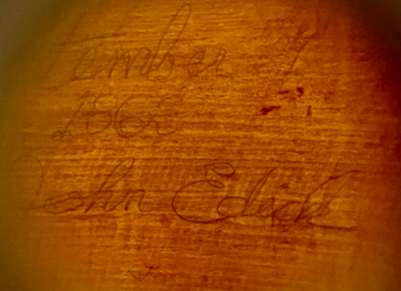

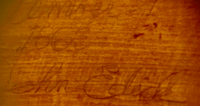

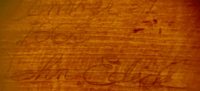

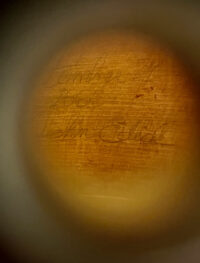

- Handwritten in pencil on the interior of the drum:

“September 1862

John Edick”

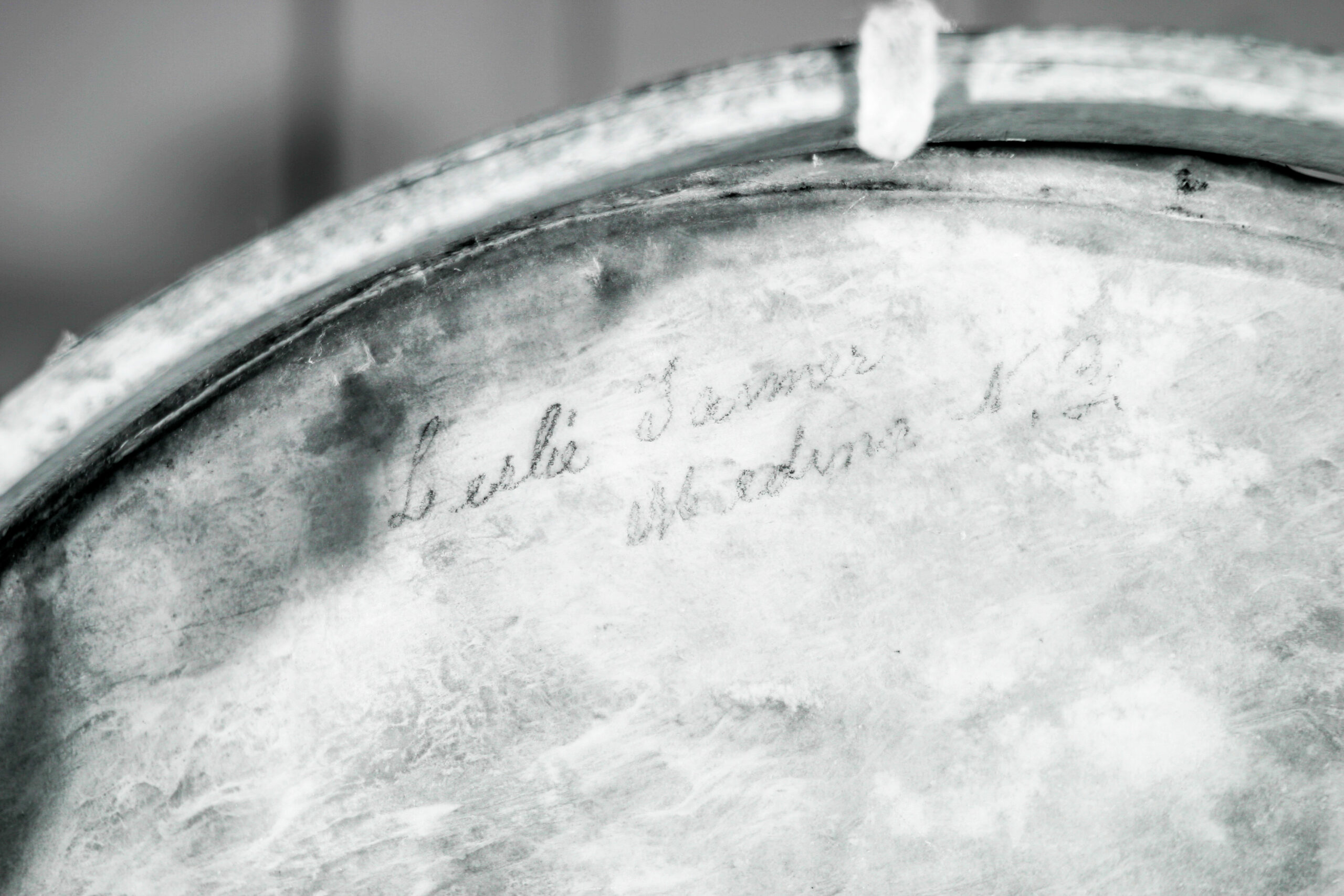

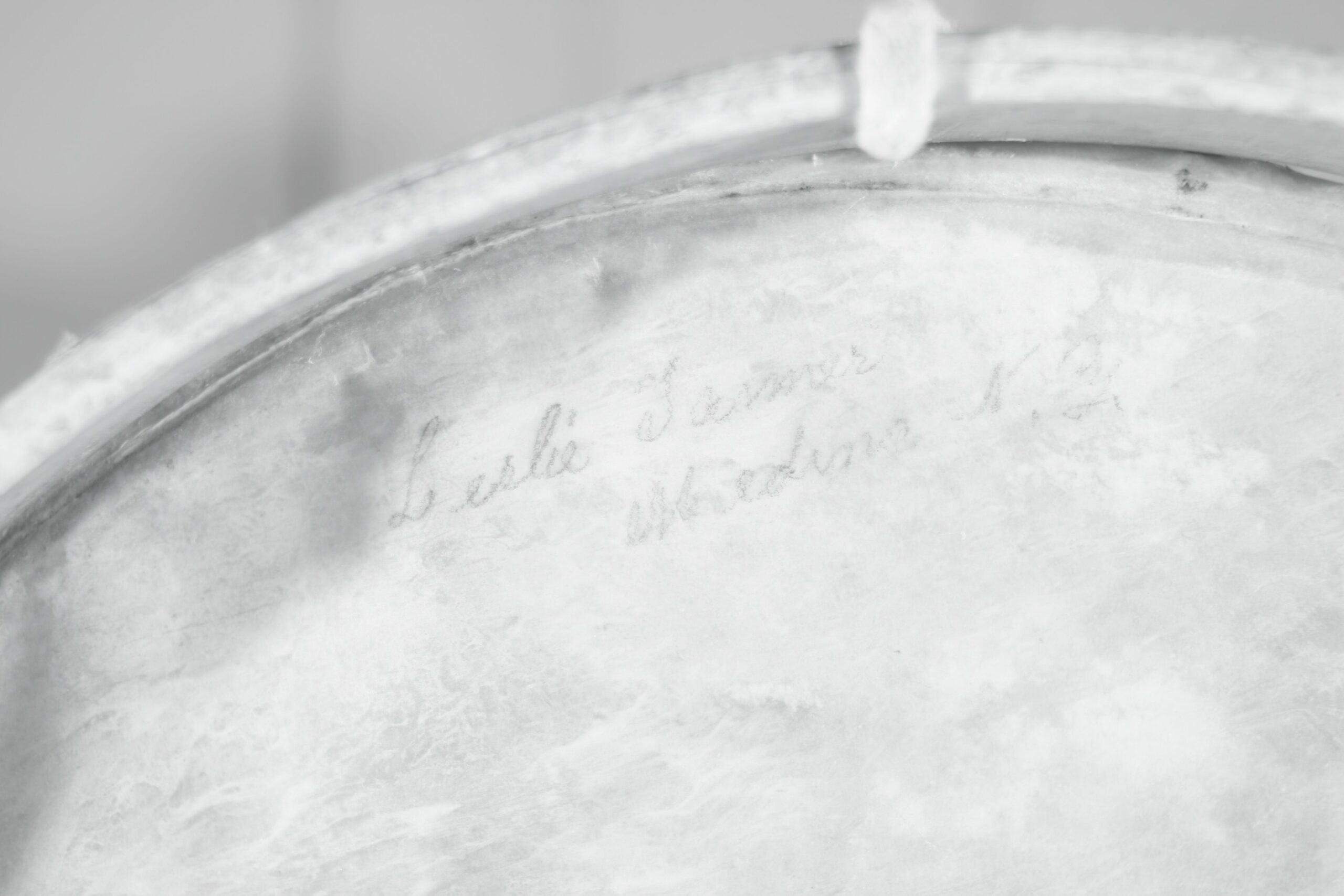

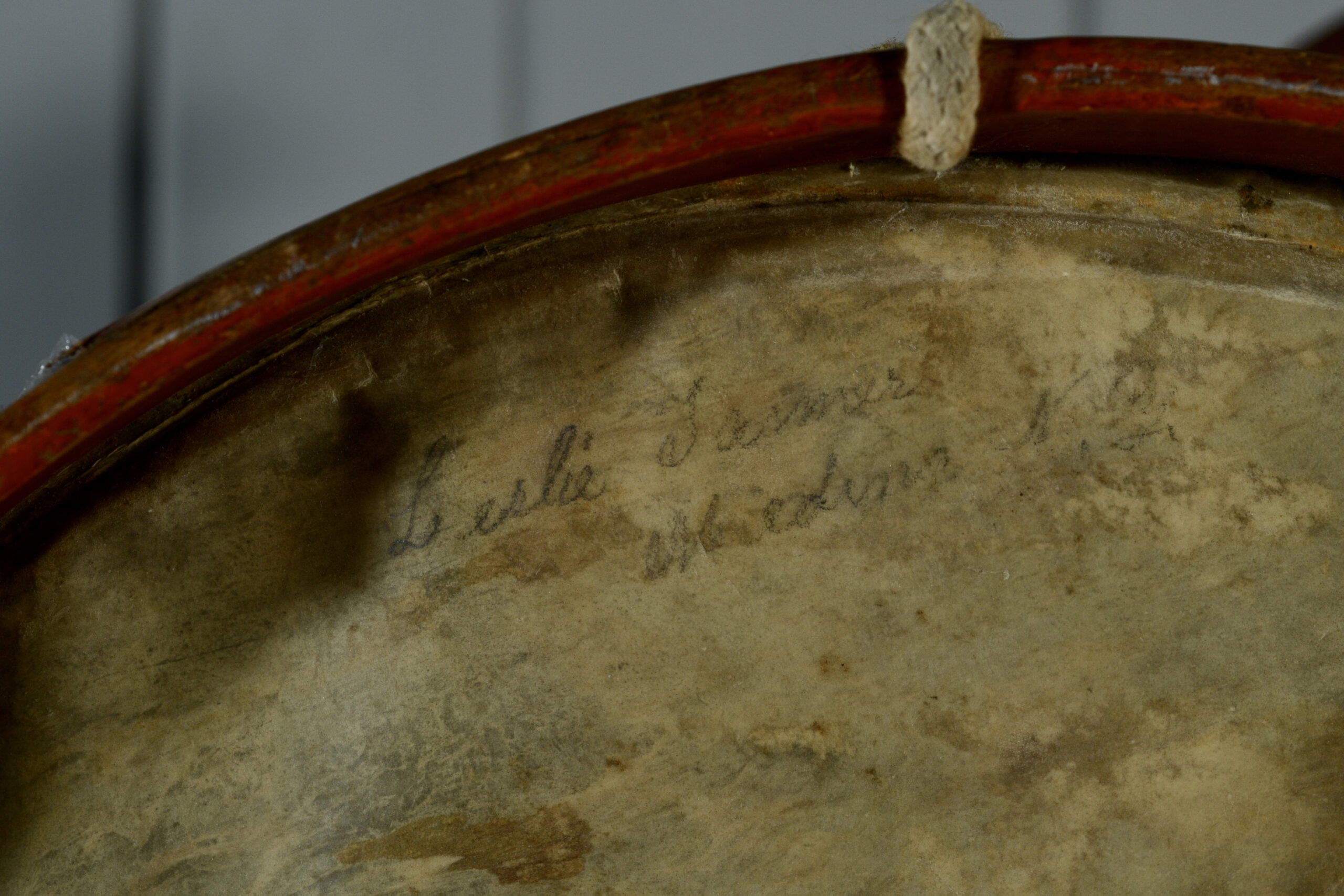

- Handwritten in pencil on the batter head:

“Leslie Farmer

Jersey City, New Jersey”

(unable to determine the identity of this individual)

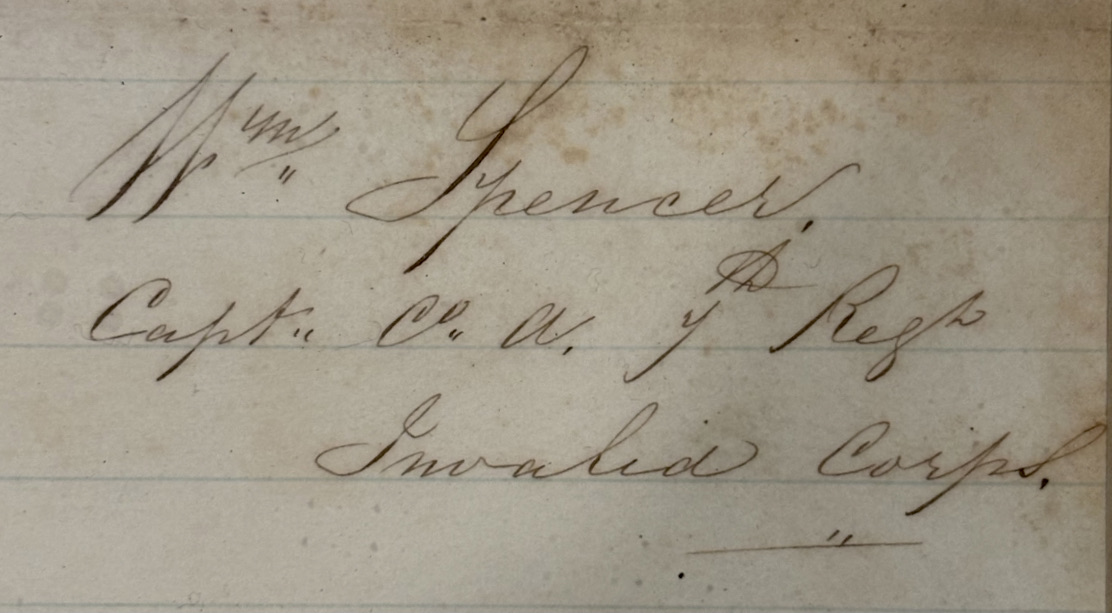

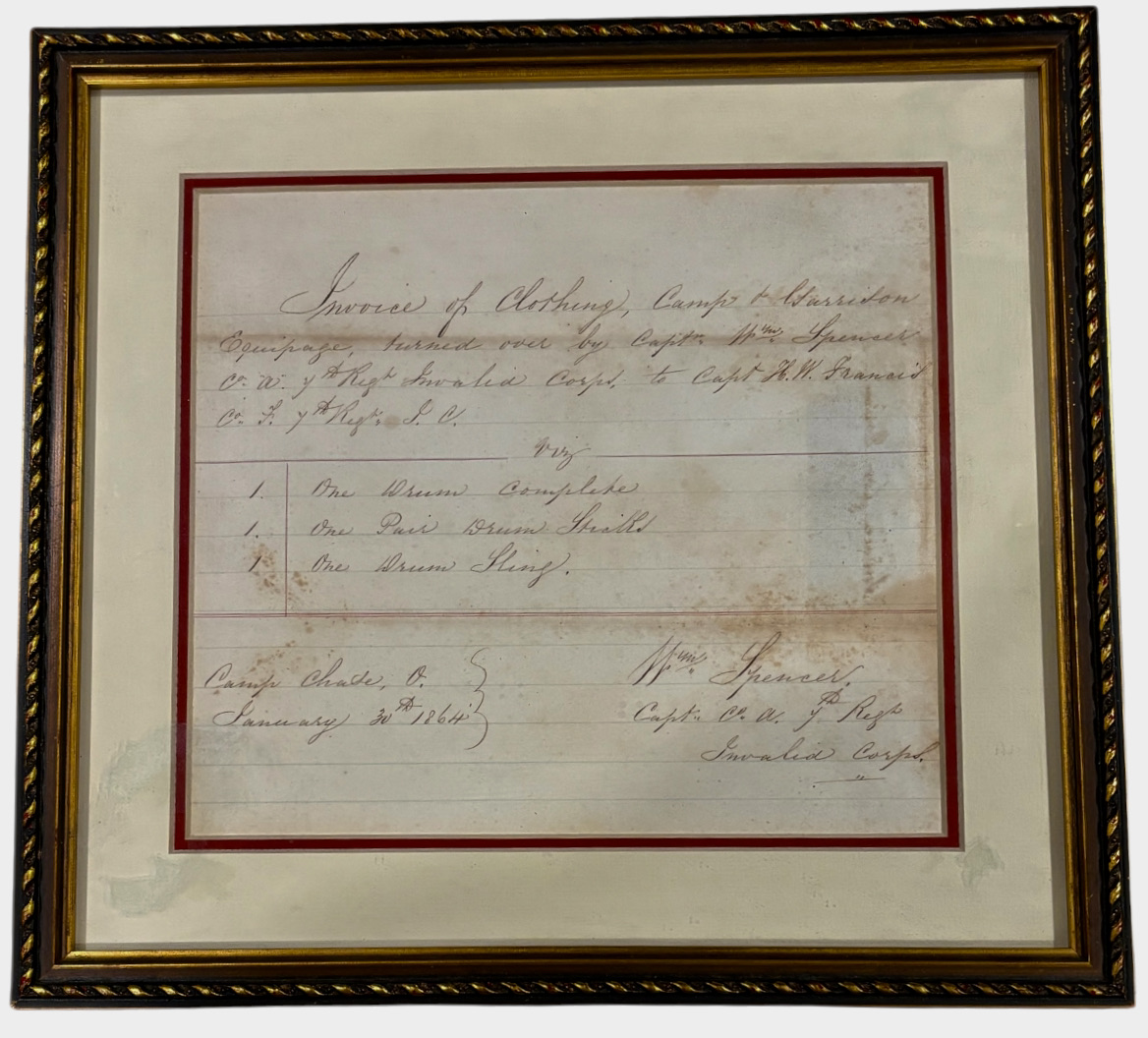

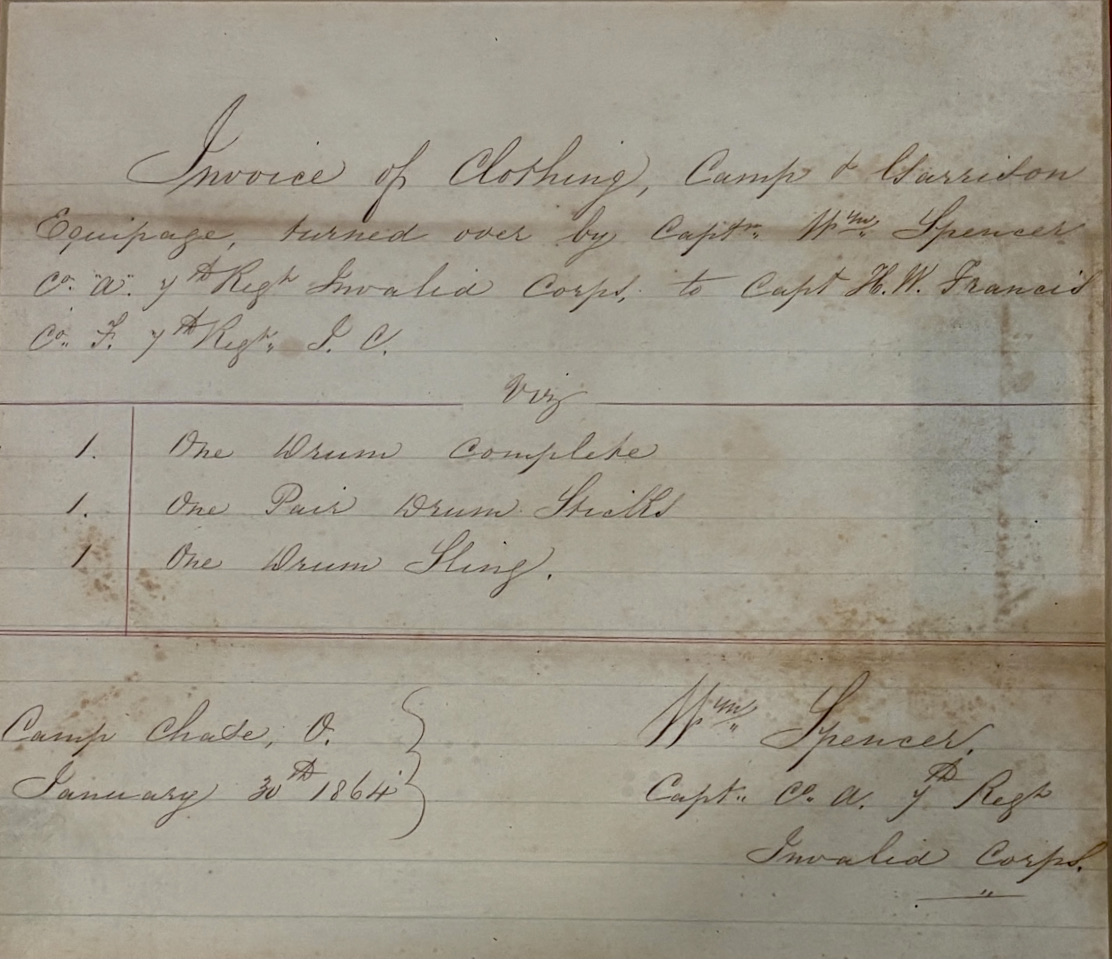

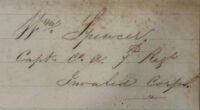

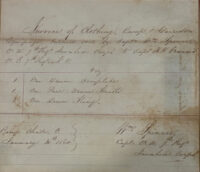

The drum is a typical, Civil War period, field drum, with rope tension and leather tension “ears”; the rope is an old replacement, although the “ears” are original. Both heads remain intact, with small hole in the upper head. The maple body exhibits a brass tack pattern surrounding the ivory rimmed sound hole. Both rims retain the majority of their original, red paint. The drum is accompanied by an original pair of sticks. Also accompanying the drum is a framed, handwritten invoice for the issue of this drum, sticks and sling (no longer present) to Co. A of the 7th Regiment of the Invalid Corps, dated January 30th, 1864. The invoice states the following:

“Invoice of clothing, camp & garrison

equipage, turned over by Capt. Wm Spencer

Co “a” 7th Regt Invalid Corps to Capt. H. W. Francis

Co F 7th Regt I.C.

?

1 One Drum Complete

1 One Pair Drum Sticks

1 One Drum Sling

Camp Chase, O. Wm. Spencer

January 30th, 1864 Capt. Co a. 7th Regt

Invalid Corps”

This is, as mentioned, the first drum we have seen that is identified to the Invalid Corps, with an invoice for the issuing of this exact drum and sticks to the I.C. regiment named on the drumhead. In addition, two soldiers’ names are written on the drum, one having served in a Pennsylvania infantry regiment, the other served in a New York, infantry regiment.

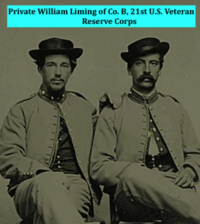

Soldiers Identified on the Drum:

Frederick Bellinger

Residence was not listed; 26 years old.

Enlisted on 9/20/1862 at Harrisburg, PA as a Priv.

On 9/20/1862, he mustered into “A” Co. Pennsylvania 56th Infantry.

He was discharged on 7/8/1865

Born in 1835

Died in 1902 in Allegan County, MI

Buried: Oakwood Cemetery, Allegan, Allegan County, MI

After the war, he lived in Allegan County, MI

56th PA Infantry

Organized: Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, PA on 3/7/1862

Mustered out: 7/1/1865

PENNSYLVANIA 56TH INFANTRY (Three Years) Fifty-sixth Infantry.-Cols., Sullivan A. Meredith, J. William Hofmann Henry A. Laycock, Lieut.-Cols., J. William Hofmann, George B. Osborn, John T. Jack, Henry A. Laycock, John Black; Majs., John B. Smith John T. Jack, H. A. Laycock, J. Black, George T. Michaels. The 56th regiment was recruited principally from Philadelphia, and the counties of Indiana, Center, Luzerne, Schuylkill, Susquehanna and Wayne in the autumn of 1861, and rendezvoused at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg. All the field officers had served in the three months, campaign. The ranks of the regiment filled very slowly, and it finally left for Washington on March 8, 1862, with only eight and one-half companies. Remaining encamped there until the following April, it did guard duty at Budd’s ferry for a short time, moving to Acquia landing on the 24th. On May 1O five companies moved to Belle Plain; on the 21st the regiment moved to Potomac creek; thence to Fredericksburg on the 27th, served there on patrol and picket duty until Aug. 9, when it was assigned to Doubleday’s brigade Kings division, McDowell’s corps. Crossing the Rappahannock it first came under fire at Rappahannock Station and first engaged the enemy at Gainesville, where Col. Meredith was severely wounded. It was active in the second Bull Run fight, being unfortunate enough to lose its colors to the enemy here. After the battle it retreated with the army to Centerville and thence to Fairfax Court House. On Sept. 6, it was ordered to Leesburg and soon after moved with McClellan on the Maryland campaign, being active at South Mountain, where it suffered severely, but it escaped with slight loss at Antietam, being on the extreme right of Hooker’s corps. On Nov. 2, having moved forward to Union in support of Pleasonton’s cavalry, the brigade, under Lieut.-Col. Hofmann, drove the enemy from the town, the 56th losing 5 killed and 10 wounded in the action, being complimented by its division commander for gallantry. It participated in the Fredericksburg campaign without loss, encamped for the winter at Pratt’s landing, Potomac creek; shared in the “Mud March,” in Jan., 1863; and on April 28, with 21 officers and 289 men, embarked on the Chancellorsville campaign, meeting with small loss during the early part of the battle. It encamped near the Fitzhugh house until June 7, when it moved to Kelly’s and Beverly fords as a cavalry support, two companies under Capt. Runkle repelling a furious charge at the latter on the 9th. Assigned to the 1st brigade (Gen. Cutler), 1st division (Gen. Wadsworth), 1st corps (Gen. Reynolds), it commenced its march towards Gettysburg on June 25, 1863. The 1st brigade had the advance on the arrival of the corps at the front, and the 56th was the first to get into position. As the enemy was at that moment advancing and within range, it was promptly ordered to fire, which opened the great battle. Brig.-Gen. Cutler, in a letter to Gov. Curtin, dated Nov. 5, 1863, stated among other things: “I hope that you will cause proper measures to be taken to give that regiment (the 56th) the credit, which is its due, of having opened that memorable battle”. In the first day’s fighting the 56th lost 4 officers and 146 men killed, wounded and missing, but its loss was small the following two days. It cared in the pursuit of Lee’s army which ensued. In November of this year it participated in the Mine Run movement with small loss, and shared in the demonstration at Raccoon ford in Feb., 1864. On March 1O, a large part of the regiment reenlisted for an additional three years and returned to Pennsylvania on veteran furlough, rejoining the army at the front on April 20. Shortly afterward the 56th entered on the Wilderness campaign. It met with heavy losses at the Wilderness, where it displayed conspicuous valor; drove the enemy from an orchard and farm house on the hill in the battle of Laurel hill; was continuously occupied in the vicinity of Spottsylvania Court House until the 21st, crossed the North Anna river at Jericho ford, where it checked the enemy’s advance and captured several hundred prisoners, was active without loss at Bethesda Church, shared the general fortunes of the army until it arrived in front of Petersburg on June 17; took part in a desperate assault on the works on the 18th; and from that time on was employed in the general work of the siege. In August it was engaged with its corps on the Weldon railroad and again on the following day, when the regiment captured the battle flag of the 55th N. C., thus avenging the loss of its own colors at the second Bull Run. James T. Jennings of Co. H was awarded a medal of honor by the secretary of war for his gallantry in securing this stand of colors. The 56th occupied the works until Sept. 13, when its corps was consolidated into one division, which became the 3rd division of the 5th corps, the 56th being assigned to the 3rd brigade, Col. Hoffmann commanding the brigade. It shared in the advance to Hatcher’s run in October and the raid to Hicksford in December, when it destroyed a part of the Weldon railroad, and then encamped between Lee’s mill and the Jerusalem plank road until Feb. 4, 1865. The regiment was again active at Hatcher’s run in February and had its full share in all the subsequent operations culminating in Lee’s surrender. It was mustered out of service at Philadelphia, July 1, 1865.

John R. Edick

Residence was not listed; 22 years old.

Enlisted on 9/5/1862 at Olcott, NY as a Priv.

On 10/22/1862, he mustered into “K” Co. New York 151st Infantry.

He was discharged on 5/16/1865

Intra-regimental company transfers

- 12/21/1864 From company K to company A

151st NY Infantry

Organized: Lockport, NY on 10/22/1862

Mustered out: 6/26/1865

NEW YORK ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-FIRST INFANTRY (Three Years) One Hundred and Fifty-first Infantry.-Col., William Emerson; Lieut.-Cols., Ewen A. Bowen, Thomas M. Fay, Charles Bogardus; Majs., Thomas M. Fay, James A. Jewell. This regiment, recruited in the counties of Niagara and Monroe, was organized at Lockport where it was mustered into the U. S. service Oct. 22, 1862, for three years. It received the men recruited for Col. Franklin Sidway’s Buffalo regiment, which served to complete its organization. The regiment left the state on the 23d and was stationed at Baltimore until the following February, when it was ordered to West Virginia, serving there and at South mountain, Md., until July 10, 1863, when it joined the 3d corps and was assigned to the 3d brigade, 3d (French’s) division, in which it was present at the action of Wapping heights. In August it was placed in the 1st brigade, same division and corps, and was present, but met with no loss, at McLean’s ford, Catlett’s station and Kelly’s ford. During the Mine Run campaign it was sharply engaged at Locust Grove, losing 60 killed, wounded and missing, and upon returning from this campaign went into winter quarters at Brandy Station. When the 3d corps was discontinued in March, 1864, the 151st was placed in the 1st brigade, 3d (Ricketts) division, 6th corps, with which it did its full share in the fighting from the Wilderness to Petersburg, being engaged at the Wilderness, Spottsylvania, North Anna, Totopotomy, and Cold Harbor. On July 6, during Early’s invasion of Maryland it moved with its division to Baltimore and was heavily engaged at Monocacy, losing 118 killed, wounded and missing. As a part of the Army of the Shenandoah it took part in Sheridan’s brilliant campaign in the Valley, fighting at Charlestown, Leetown, Smithfield, Opequan, Fisher’s hill and Cedar creek, with a loss of 38 in the campaign. In December it returned to the Petersburg trenches and was stationed near the Weldon railroad through the winter. On Dec. 21, 1864, its thinned ranks were consolidated into a battalion of five companies. In April, 1865, it took part in the final assault on the works of Petersburg and the ensuing hot pursuit of Lee’s army, fighting its last battle at Sailor’s creek. Its loss in the Appomattox campaign was 18 killed and wounded. The regiment was finally mustered out near Washington, D. C., June 26, 1865, under command of Lieut.-Col. Bogardus. It lost during service 5 officers and 101 men killed and mortally wounded; 1 officer and 99 men died of disease and other causes; total deaths, 206.

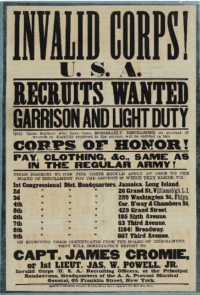

Invalid Corps

The Veteran Reserve Corps (originally the Invalid Corps) was a military reserve organization created within the Union Army during the American Civil War to allow partially disabled or otherwise infirm soldiers (or former soldiers) to perform light duty, freeing non-disabled soldiers to serve on the front lines.

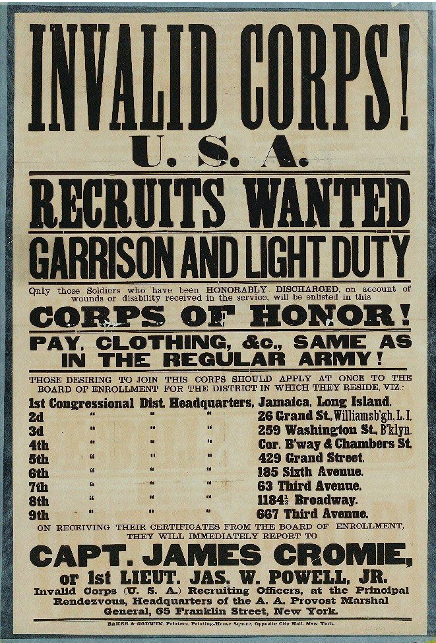

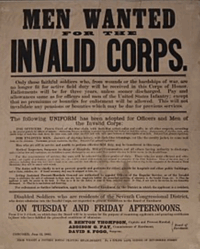

The Invalid Corps

The corps was organized under authority of General Order No. 105, U.S. War Department, dated April 28, 1863. A similar corps had existed in Revolutionary times between 1777 and 1783. The Invalid Corps of the Civil War period was created to make suitable use in a military or semi-military capacity of soldiers who had been rendered unfit for active field service on account of wounds or disease contracted in line of duty, but who were still fit for garrison or other light duty, and were, in the opinion of their commanding officers, meritorious and deserving.

Qualifications

Those serving in the Invalid Corps were divided into two classes:

- Class 1, partially disabled soldiers whose periods of service had not yet expired, and who were transferred directly to the Corps, there to complete their terms of enlistment;

- Class 2, soldiers who had been discharged from the service on account of wounds, disease, or other disabilities, but who were yet able to perform light military duty and desired to do so.

As the war went on, it proved that the additions to the Corps hardly equaled the losses by discharge or otherwise, so it was finally ordered that the men who had had two years of honorable service in the Union Army or Marine Corps might enlist in the Invalid Corps without regard to disability.

The Veteran Reserve Corps

The title “Veteran Reserve Corps” was substituted for that of “Invalid Corps” by General Order No. 111, dated March 18, 1864, to boost the morale as the same initials “I.C.” were stamped on condemned property meaning, “Inspected-Condemned”. The men serving in the Veteran Reserve Corps were organized into two battalions; the First Battalion including those whose disabilities were comparatively slight and who were still able to handle a musket and do some marching, also to perform guard or provost duty. The Second Battalion was made up of men whose disabilities were more serious, who had perhaps lost limbs or suffered some other grave injury. These latter were commonly employed as cooks, orderlies, nurses, or guards in public buildings.

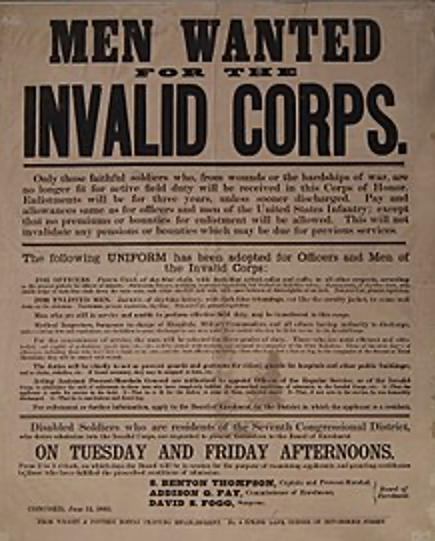

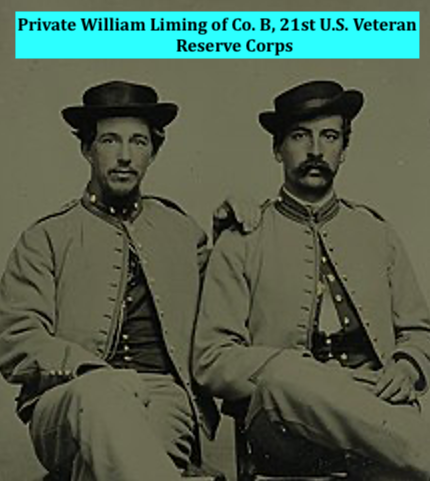

Uniforms

Invalid Corps members stood out because of their unique uniforms. According to General Orders No. 124, issued May 15, 1863,

The following uniform has been adopted for the Invalid Corps: Jacket: Of sky-blue kersey, with dark-blue trimmings, cut like the jacket of the U.S. Cavalry, to come well down on the loins and abdomen. Trousers: Present regulation, sky-blue. Forage cap: Present regulation.

The uniform was trimmed in dark blue, with chevrons of rank and the background of officer’s shoulder insignia having that color as a backing.

Invalid Corps troops also wore standard dark blue fatigue blouses from time to time. Standard forage caps were to be decorated with the brass infantry horn, regimental number, and company letter.

Officers also wore sky blue; a frock coat of sky-blue cloth, with dark blue velvet collar and cuffs, in all other respects according to the present pattern for officers of infantry. Shoulder straps were also to match current patterns but dark-blue velvet. Officers also wore gold epaulets on parade. Eventually officers were allowed to wear the standard dark-blue frock, ostensibly because sky-blue frocks soiled easily. Some officers had their frocks cut down to make uniforms or shell jackets. By the war’s end, however, the army was still making sky-blue officers’ frocks.

Organization

There were twenty-four regiments in the Corps. These regiments were organized into one division and three brigades. In the beginning, each regiment was made up of six companies of the First Battalion and four of the Second Battalion, but in the latter part of the war, this method of organization was not strictly adhered to. The 18th Regiment, for example, which rendered exceptionally good service in Virginia at Belle Plain, Port Royal, and White House Landing in the spring and early summer of 1864, and in or near Washington DC in the latter part of the summer and through the fall of that year, was made up of only six Second Battalion companies.

There were from two to three times as many men in the First Battalion as in the Second, and the soldiers in the First Battalion performed a wide variety of duties. They furnished guards for the Union prison camps at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, Elmira, New York, Point Lookout, Maryland, and elsewhere. They furnished details to the provost marshals to arrest bounty jumpers and to enforce the draft. They escorted substitutes, recruits, and prisoners to and from the front. They guarded railroads, did patrol duty in Washington DC, and even manned the defenses of the city during Jubal Early‘s raid against Fort Stevens in July 1864.

During the war, more than 60,000 men served in the Corps in the Union army; 1,700 soldiers during the service in the Federal Veteran Reserve Corps, of whom 24 died in action. Several thousand also served in a Confederate counterpart, the Southern Invalid Corps, although it was never officially organized into actual battalions.

Four members from Company F of the Fourteenth Veteran Reserves conducted the execution of the four conspirators linked to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on July 7, 1865, at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. They knocked out the post that released the platform that hanged Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt.

The Federal corps was mostly disbanded in 1866 following the close of the Civil War and the lessening of a need for reserve troops. The reorganization of the Regular Army in July 1866 provided for four regiments of the Veteran Reserve Corps. The Veteran Reserve Corps completely ceased to exist when these regiments were consolidated with other regiments in the Army’s next re-organization in March 1869.

US Military History You Should Know: Meet the Battle-Hardened Invalid Corps

In honor of Memorial Day, we invite the Cure Nation to explore our nation’s military history by learning more about the 10th Veteran Reserve Corps (Invalid Corps). When called upon to give that last measure of commitment, the devoted men of the Union Army’s Invalid Corps stood in the gap and defended President Abraham Lincoln and the Capitol at Washington D.C. toward the end of the Civil War.

By Day Al-Mohamed (Director, Executive Producer of the Invalid Corps Documentary)

The Formation of the Invalid Corps

The Civil War, one of the bloodiest wars Americans ever fought, saw many Americans on both the Union and Confederate sides killed. Also some were wounded and disabled for the rest of their lives. At first, the Union Army assumed that it would defeat the Rebels within a year, so many of the first soldiers injured in the war were allowed to return home after their injuries.

Many were missing arms, legs and/or eyesight or had mental disorders. But as the Civil War drug on, the numbers of soldiers fighting for the North as well as the South were rapidly being depleted due to death, injuries, disease and what we would call today, battlefield fatigue.

“Later in the war, instead of discharging many of the wounded soldiers, the North kept these wounded soldiers who could no longer fight in the regular army on active duty and created what was called the Invalid Corps,” Al-Mohamed reports. “This way the able-bodied men could go to the front and fight.

The men of the Invalid Corps:

- took over the responsibilities of guard duty;

- made supply runs;

- were used for parades;

- guarded the theaters;and

- did all the work that had to be done to support the army and to protect and defend the Capitol.

They oversaw the prisoners of war too and completed the clerical work needed to keep Grant’s army making more gains in conquering the South. These men were viewed as not being able to do anything else in the Union Army except participate in the Invalid Corps.”

The Civil War’s Southern Campaign Advances

General Ulysses S. Grant decided in 1864 that the time was right to try and crush the South and bring an end to this war once and for all. Grant mustered a large army to march with him and pulled just about every able-bodied soldier out of the North, including those guarding Washington D.C. to fight with him in his Southern Campaign.

In June, 1864, General Robert E. Lee, with his Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, formed the Confederate lines around Richmond. Lee ordered General Jubal Early to take a detachment of men to wage the Shenandoah Valley Campaign and clear that area. Then General Early was to proceed to Maryland to disrupt the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and, if possible, threaten Washington D.C.

Lee’s hope was that a movement into Maryland would force General Grant to send troops back to Washington to protect the Capitol and President Abraham Lincoln, thus reducing Grant’s strength to take the Confederate Capitol at Richmond, Virginia.

Because Grant had pulled almost all the able-bodied soldiers out of the North, General Early was able to go up the Shenandoah Valley all the way to Maryland and hoped to then launch an attack on Washington D.C. from the north.

Only the small Fort Stevens and its minimum number of troops plus the men of the Invalid Corps were present to defend the Capitol.

When the Union learned that General Early and the Confederates were planning to attack Washington D.C. from the north, Grant quickly sent troops back to help defend the Capitol. Grant put troops on boats that went up the Potomac River to reinforce the small band of Union troops at Fort Stevens.

The Great Civil War Race to Fort Stevens

The race was on, and could Grant’s reinforcements reach Fort Stevens in time to save the Capitol and President Lincoln? Or, would General Jubal Early and his 15,000 Confederates rout the defenders at Fort Stevens and storm the Capitol at Washington D.C., only 3 miles away?

They were caIled cowards and cripples, but to protect President Lincoln, a few disabled Union soldiers held off 15,000 Confederates.

“The men of the Invalid Corps were put outside Fort Stevens in trenches to defend the fort,” Al-Mohamed explains. “President Lincoln was in Washington at the time and went out to Fort Stevens to stand on the ramparts to watch the battle.”

As the early troops began to arrive at the breastworks of Fort Stevens, Early delayed the attack, since he still was unsure of the Federal strength defending the fort. Much of his army was still in transit to the fort too. Early’s men were exhausted due to the excessive heat (the area had had 47 days without rain and temperatures in the 90s), his troops had been on the march since June 13, and these Confederate troops had looted the home of Montgomery Blair, the son of the founder of Silver Springs, Maryland, and had partaken of the barrels of whiskey at the mansion. Many of the troops – new recruits with little or no experience in combat – were too drunk to go into battle.

However, the men of the Invalid Corps were battle-hardened veterans who had looked death in the face and kept on fighting.

This is one of the main reasons the men of the Invalid Corps were put in the trenches of Fort Stevens to defend against the Rebel charge.

One major road came into Washington D.C. from the north, and that was the road where Fort Stevens had been set up to protect.

Perhaps President Lincoln thought that by being on the ramparts he could rally the troops to defend the Capitol. During one of the skirmishes while President Lincoln was standing on the wall of the fort, a surgeon standing nearby was shot by a Confederate soldier. Although several skirmishes occurred during the battle for Fort Stevens, the Invalid Corps and the soldiers inside the fort stood their ground.

“One year after the battle, the men who fought in the Invalid Corps protested the name of their unit, so the name was changed to the Veteran Reserve Corps,” Al-Mohamed says. “By the end of the Civil War, more than 40,000 soldiers were in the Veteran Reserve Corps.

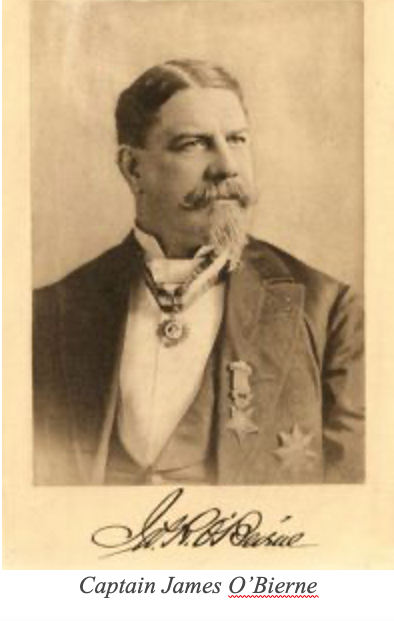

One of the members of the Veteran Reserve Corps, Captain James O’Bierne, had suffered an injury from a bullet ricocheting off his head, had a second bullet in his leg, had been shot in his chest and had a paralyzed right arm. He was detailed to the Provost Marshall’s Office and put in charge of getting the arms and the ammunition for the men who fought at Fort Stevens.

He also took care of the wounded, buried the dead, oversaw the care of prisoners and was assigned to chase General Early and his command after the attack on Fort Stevens. Later, almost immediately after the end of the war, when President Lincoln was shot on April 14, 1865, and died the next day, O’Bierne was assigned to do the detective work to find John Wilkes Booth.”