ShopJanuary 23, 2026

-

Civil War Pipe Carved by a Soldier in Co. C of the Famed 5th New York Infantry or Duryee’s Zouaves

$1,350Civil War Pipe Carved by a Soldier in Co. C of the Famed 5th New York Infantry or Duryee’s ZouavesJanuary 23, 2026 -

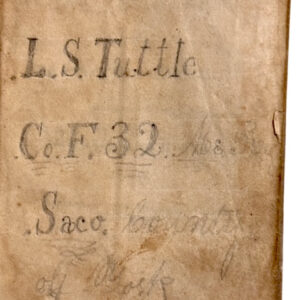

Id’d Civil War Period Pocket Bible – Lewis S. Tuttle Co. F 32nd Maine Infantry – POW and Died at Andersonville

$650Id’d Civil War Period Pocket Bible – Lewis S. Tuttle Co. F 32nd Maine Infantry – POW and Died at AndersonvilleJanuary 22, 2026 -

Pre-War to Civil War Period Cased Surgeon’s Kit by George Tiemann of New York

$3,250Pre-War to Civil War Period Cased Surgeon’s Kit by George Tiemann of New YorkJanuary 22, 2026 -

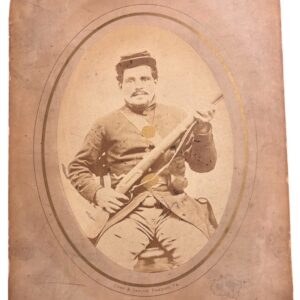

Id’d Albumen of Private John A. Bensing Co. F 87th Illinois Infantry

$275Id’d Albumen of Private John A. Bensing Co. F 87th Illinois InfantryJanuary 18, 2026 -

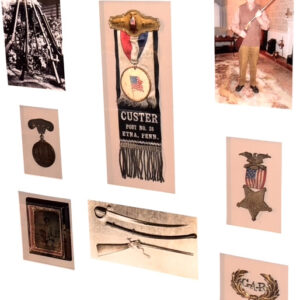

Id’d Grouping Civil War Soldier – Sergeant William Wyble Co. F 5th West Virginia Cavalry

$850Id’d Grouping Civil War Soldier – Sergeant William Wyble Co. F 5th West Virginia CavalryJanuary 18, 2026 -

Dug Civil War Officer’s Whiskey Decanter from Union Camp at Brandy Station

$65Dug Civil War Officer’s Whiskey Decanter from Union Camp at Brandy StationJanuary 17, 2026 -

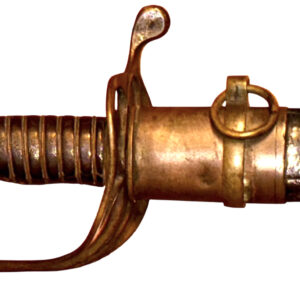

Dug Confederate Kenansville Cavalry Saber and Scabbard

$750Dug Confederate Kenansville Cavalry Saber and ScabbardJanuary 17, 2026 -

Id’d Boyle and Gamble Foot Officer’s Sword and Leather Scabbard

Id’d Boyle and Gamble Foot Officer’s Sword and Leather ScabbardJanuary 16, 2026 -

General Officer’s Hat Cords – Indian War Period to Spanish-American War

General Officer’s Hat Cords – Indian War Period to Spanish-American WarJanuary 15, 2026 -

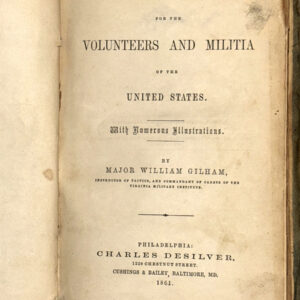

Id’d Confederate Officer’s Military Manual – “Manual of Instruction for the Volunteers and Militia of the United States” Major William Gilham, Published in 1861 – Inked and Written inside the Manual – 1st Lt. E.F. Cowherd Adj. 13th Va. Infantry

$750Id’d Confederate Officer’s Military Manual – “Manual of Instruction for the Volunteers and Militia of the United States” Major William Gilham, Published in 1861 – Inked and Written inside the Manual – 1st Lt. E.F. Cowherd Adj. 13th Va. InfantryJanuary 14, 2026 -

Civil War Friction Primer Tin Boxes

$295Civil War Friction Primer Tin BoxesJanuary 6, 2026 -

Civil War Union 2nd Lieutenant of the Infantry Fatigue Blouse or Sack Coat

$3,750Civil War Union 2nd Lieutenant of the Infantry Fatigue Blouse or Sack CoatJanuary 6, 2026 -

Civil War Brass Band Drum Major’s Baton or Mace

$450Civil War Brass Band Drum Major’s Baton or MaceJanuary 2, 2026 -

Civil War US Army Issue Brogan or Jefferson Bootee Excavated at Ft. Pembina in North Dakota

$850Civil War US Army Issue Brogan or Jefferson Bootee Excavated at Ft. Pembina in North DakotaDecember 31, 2025 -

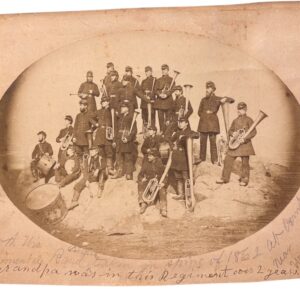

Albumen of the 5th Wisconsin Regimental Band – Image Taken at Camp Griffin, Va. in 1861

Albumen of the 5th Wisconsin Regimental Band – Image Taken at Camp Griffin, Va. in 1861December 31, 2025 -

Pattern 1853 Enfield or Tower Rifled Musket with Original Bayonet – Lock Dated 1862

$1,750Pattern 1853 Enfield or Tower Rifled Musket with Original Bayonet – Lock Dated 1862December 30, 2025 -

Confederate Crudely Made Cone-Shaped Clay Inkwell

Confederate Crudely Made Cone-Shaped Clay InkwellDecember 29, 2025