Important Confederate Officer Grouping – Capt. C.H. Dimmock, C.S. Engineer – The Dimmock Line

$37,500

Important Confederate Officer Grouping – Capt. C.H. Dimmock, C.S. Engineer – The Dimmock Line – This is perhaps the finest grouping we have had, to date, of an important Confederate officer’s effects. The components of this grouping belonged to Capt. Charles H. Dimmock, the Confederate engineer who designed and implemented the construction of the famed “Dimmock Line”, a lengthy and robust series of entrenchments and fortifications that surrounded the city of Petersburg, Virginia, an important rail hub and focal point for the transport of much needed military materiel for the Confederacy. Dimmock’s work was so appreciated by the citizenry of the City of Petersburg, that they presented him, in 1864, a horse accompanied by a set of finely appointed, custom made, English horse tack and saddle valise. Indeed, Dimmock earned the praises of many Confederate officers for his engineering feats, including General William Mahone, famed for his re-taking of the Crater, shortly after the explosion of the Federal mine, on July 30, 1864. Dimmock would be a pivotal figure in maintaining the many miles of Confederate earthworks and forts, during the nine month Siege of Petersburg. When the city fell, on April 2, 1865, Dimmock retreated with General Lee’s army and was ultimately paroled, at Appomattox, on April 10, 1865.

The following, from a variety of research sources noted at the end of this synopsis, summarizes Captain Dimmock’s life:

“Charles Henry Dimmock was born in Baltimore, on October 18, 1831. His family afterwards settled in Richmond, where his father became the city surveyor. Dimmock studied mathematics and engineering under Claude Crozet, who was Principal Engineer and Surveyor for the Virginia Board of Public Works and a founder of the Virginia Military Institute. Under Crozet’s direction, Dimmock worked as engineer on various civil projects in Virginia — primarily roads and railroads. With the start of the Civil War, Dimmock was commissioned captain of engineers in the Confederate States Army. Undoubtedly, his career was aided by the fact that his father, Col. Charles Dimmock Sr., was by this time Chief of Ordnance for the state of Virginia and Inspector of Richmond’s fortifications.

Despite a lack of military experience, one of Dimmock’s early war assignments was to oversee construction of fortifications on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. These works were not considered successful. He then returned to Virginia to oversee work on the Yorktown fortifications with others. As McClellan’s army moved up the Peninsula toward Richmond, Capt. Dimmock was sent to Petersburg to obstruct the Appomattox River to stymie the approach of Union gunboats. Dimmock then worked on a new military railroad bridge over the Appomattox.

With the departure of Gilmer and Stevens, Capt. Dimmock inherited the formidable task of fortifying the city. Military affairs in North Carolina in November and December drew off most of the soldiers and slave owners demanded the return of their property, leaving him starved for labor. Dimmock solved the problem by establishing a skilled cadre of 200 free black and slave workers who worked from 8 am until 4 pm daily for regular wages. After that, the work proceeded slowly but steadily.

Anticipating attack from the direction of City Point, much labor was lavished on the eastern front from the Appomattox River past the Jerusalem Plank Road. Beyond that the works were more or less sketched in — artillery batteries were started, connecting infantry lines were left until manpower was available.”

“Civil War Service

After the Virginia convention voted to secede from the United States in April 1861, Dimmock returned to Richmond. He supervised construction of defenses at Fort Norfolk, at Craney Island near Portsmouth, and at Roanoke Island in Dare County, North Carolina, before he received a commission on 17 May as a captain in the Corps of Engineers of the Provisional Army of Virginia. In mid-October, Dimmock was assigned to Gloucester Point on the York River. Noting his ability, his superiors recommended him early in 1862 for a position in the nascent Confederate Corps of Engineers. Dimmock mustered in at the lower rank of first lieutenant. On 12 February 1862 he protested his demotion in a letter to the Confederate secretary of war and on 18 March won reinstatement as captain.

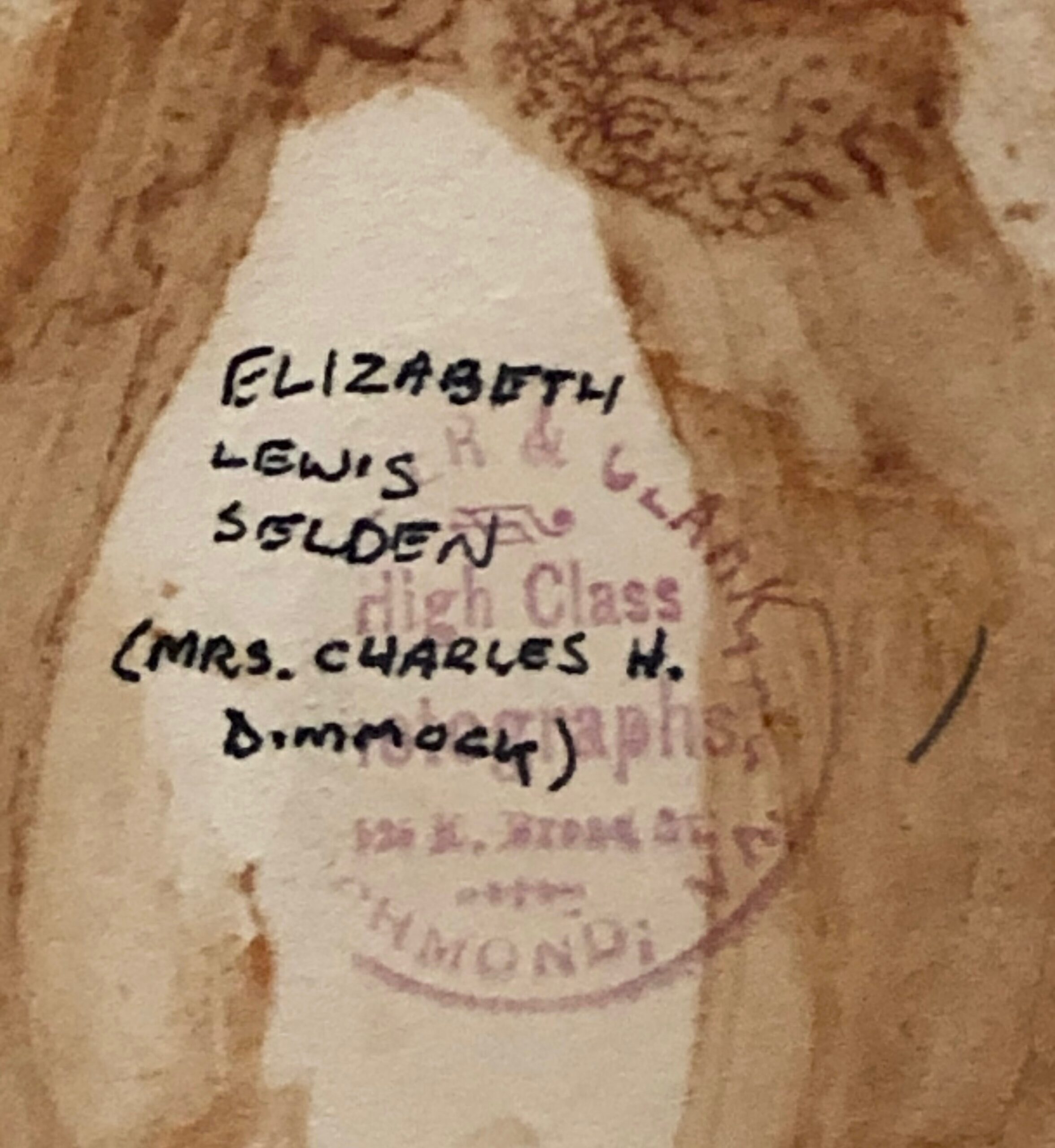

In May 1862 Dimmock was dispatched to build obstructions in the Appomattox River near Petersburg in response to the Union campaign on the Peninsula. After initial surveys conducted by others in August 1862, Dimmock began the design and then directed the construction of a system of defenses—ten miles of fortifications and fifty-five batteries around the city of Petersburg—that would later be known as the Dimmock Line. He required a large labor force, and slaves made up for the shortage of white Confederate manpower. Having completed the project by the middle of 1863, Dimmock had begun supervising the construction of a new bridge across the Appomattox River by July. In Richmond on 14 October 1863 he married Elizabeth Lewis Selden. They had four daughters and one son.

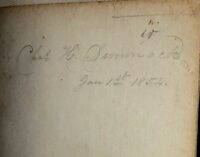

In honor of Dimmock’s dedication to the defense of their city, Petersburg residents presented him with a stallion and riding equipment in January 1864. Later that year the Dimmock Line held against a Union attack on 9 June. Dimmock was reassigned in December to the Army of Northern Virginia, with which he served until the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865. Dimmock took the amnesty oath on 25 May and returned to Richmond, where he resumed his civilian life as an architect and civil engineer. He tried his hand at literary pursuits and published a twenty-four-page poem, The Modern: A Fragment (1866), in which he condemned the vapid nature of modern society.

Monument to the Confederate Dead

With the cessation of hostilities, Richmonders quickly mobilized a campaign for Confederate memorialization. A bazaar held by the Hollywood Memorial Association of the Ladies of Richmond in April 1867 raised $18,000 for the purpose of erecting a monument in Hollywood Cemetery for all Confederate soldiers. Dimmock submitted a design to the selection committee in June. He envisioned a ninety-foot-tall pyramid, made of local stone, held together without mortar, and perhaps covered in creeping ivy. The Hollywood Memorial Association selected his design and laid the cornerstone on 3 December 1868. To great fanfare spectators watched a convict climb ninety feet to the top to place the capstone on 8 November 1869. The pyramid became an enduring symbol of the Lost Cause and a tourist destination at the historic cemetery into the twenty-first century.

Civil Engineer

By 1870 Dimmock had established an architectural firm on Main Street with his younger brother, Marion Johnson Dimmock. On 27 April 1870 the overloaded courtroom floor at the Capitol collapsed, killing about sixty people. Dimmock served on the three-member committee that the General Assembly named to assess the damage and recommend a course of action. In its report presented on 17 May, the committee proposed repairing the Capitol rather than constructing a new building. The assembly granted funds the next month for the suggested repairs and construction.

As part of a slate of Conservative candidates, Dimmock won election as city engineer of Richmond on 26 May 1870. His duties included maintaining and paving streets and sidewalks, maintaining sewers, building bridges, planting trees, and supervising school construction. In March 1871 a group of local builders brought charges of incompetence and price-gouging against Dimmock, but the city council quickly exonerated him and the following year reelected him to the post of engineer. Early in 1872 the Hollywood Memorial Association sent Dimmock to Gettysburg to monitor the ongoing exhumation of Confederate dead from the battlefield. His report to the organization that April expressed his shock at the desecration of the graves by local farmers and recommended that the removal of remains to Hollywood continue.

By that time Dimmock’s health had begun to deteriorate from stomach cancer. In January 1873 he traveled to New York City for an operation. His illness worsened, however, and during the night of 28, 29 March 1873 Charles Henry Dimmock died at his father-in-law’s home in Gloucester County. He was buried at Hollywood Cemetery, in Richmond. As a testament to his civic service, Richmond’s mayor closed government offices at noon. More than a century after his death a parkway in Colonial Heights, near Petersburg, was named for Dimmock.

Sources Consulted:

Charles H. Dimmock Papers (including birth date in MS biography and death date of 29 Mar. 1873 on copy of 1865 parole), Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Va.; correspondence, lines of verse, drawings, commonplace book, and diary (1859) in Charles H. Dimmock Papers, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Va.; Baltimore Sun, 16 May 1857; Marriage Register, Richmond City (1863), Bureau of Vital Statistics, Record Group 36, Library of Virginia; Richmond Daily Dispatch, 30 Mar. 1871; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers (1861–1865), War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (1880–1901); Mary H. Mitchell, Hollywood Cemetery: The History of a Southern Shrine (1999), portrait tipped in between 34 and 35; A. Wilson Greene, Civil War Petersburg: Confederate City in the Crucible of War (2006); Gloucester Co. Death Register (died on 29 Mar. 1873); obituaries in Richmond Daily Dispatch, Richmond Enquirer (with variant birth date of 31 Oct. 1831), and Richmond Daily Whig, all 1 Apr. 1873 (died “Friday last,” 28 Mar. 1873), and in Baltimore Sun, 2 Apr. 1873 (died “on Friday”).”

This fine grouping includes a large array of Dimmock related items, to include the following:

Dimmock Grouping Contents

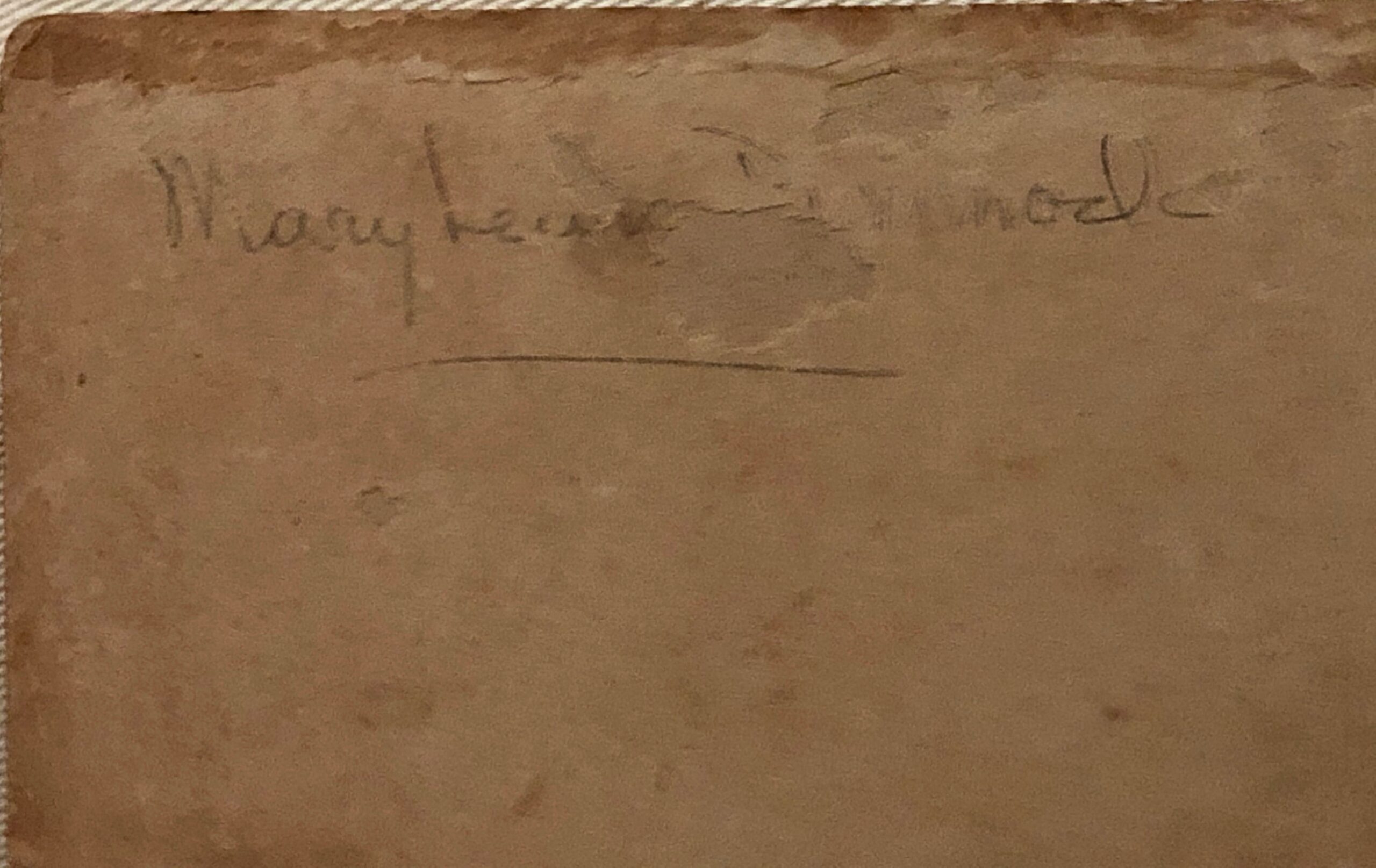

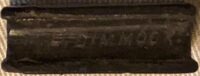

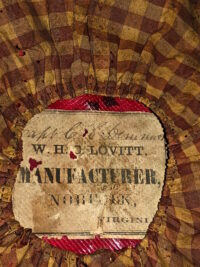

- Dimmock’s Confederate officer’s forage / kepi cap; constructed of a fine, black, English broadcloth wool; quartrefoil on the cap is the rarely encountered, “rope-like” or rounded bullion; Dimmock wrote his name in the cap’s crown, on the maker’s label – chin strap, side buttons are missing – most likely removed in response to Federal dictates that surrendered officers could no longer wear Confederate insignia; a “ghost” of the manuscript “E” insignia (listed below) remains clearly visible on the front of the cap; the lining is a checked, light cotton gingham; the sweat band, constructed of fine, Moroccan leather, is complete; hat exhibits Dimmock’s arduous field work, but remains in overall, very good condition

- Dimmock’s sash – wide, maroon silk; full length; in good condition

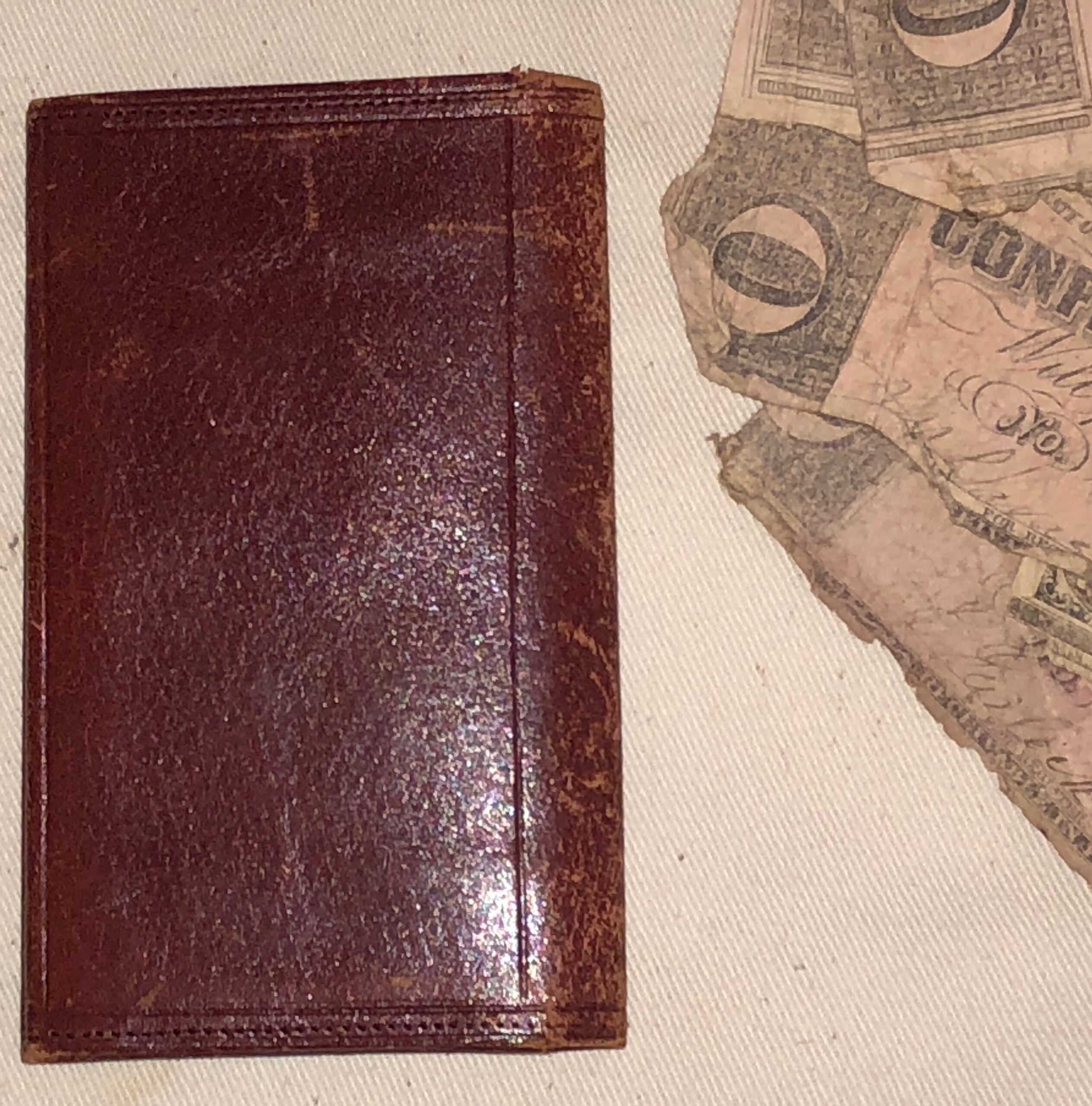

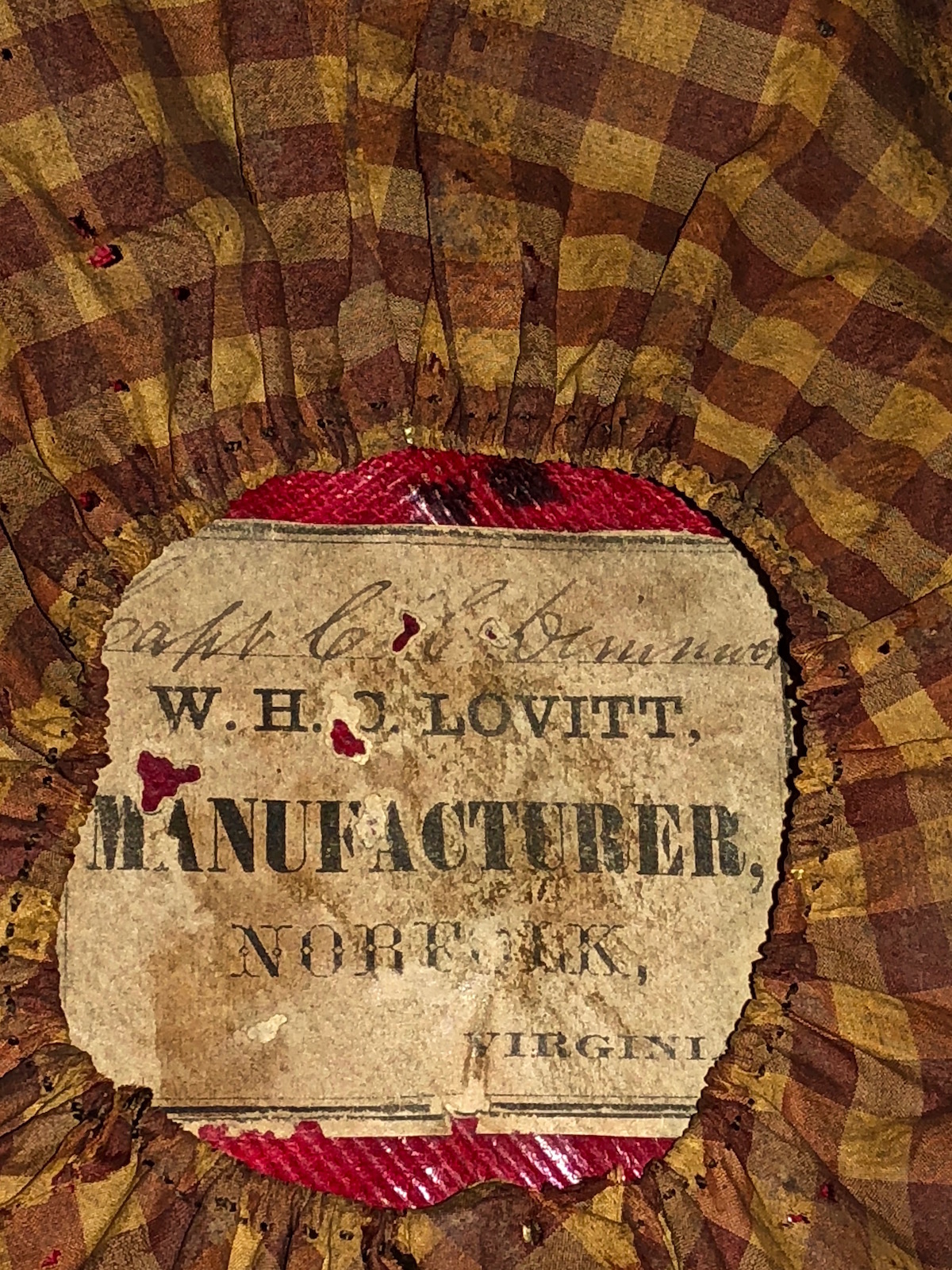

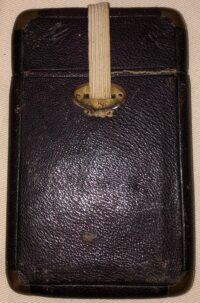

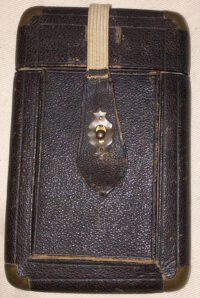

- Dimmock’s saddle valise – russet brown, English leather; mint condition; this is the valise presented to the Captain by the citizens of Petersburg

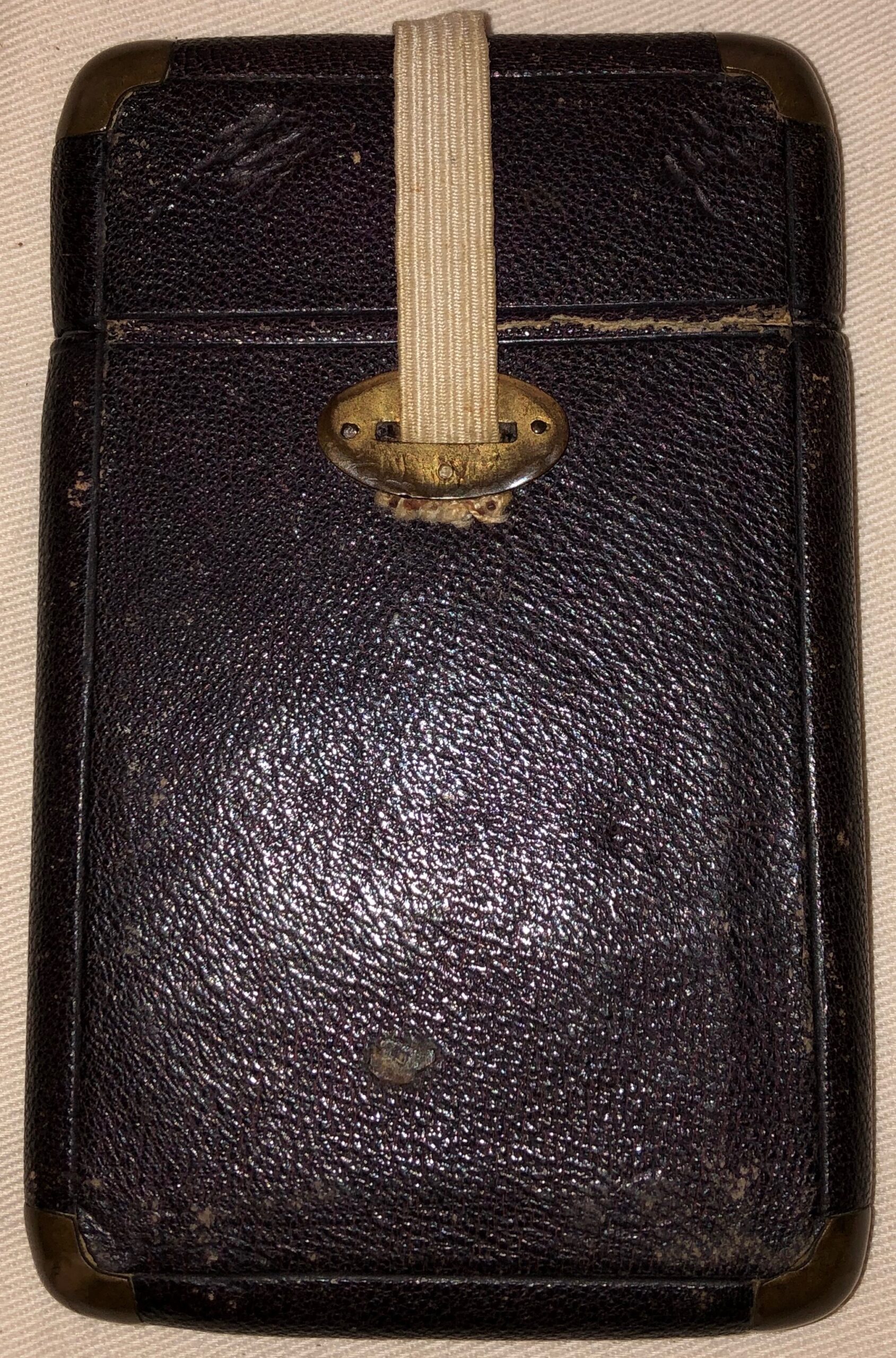

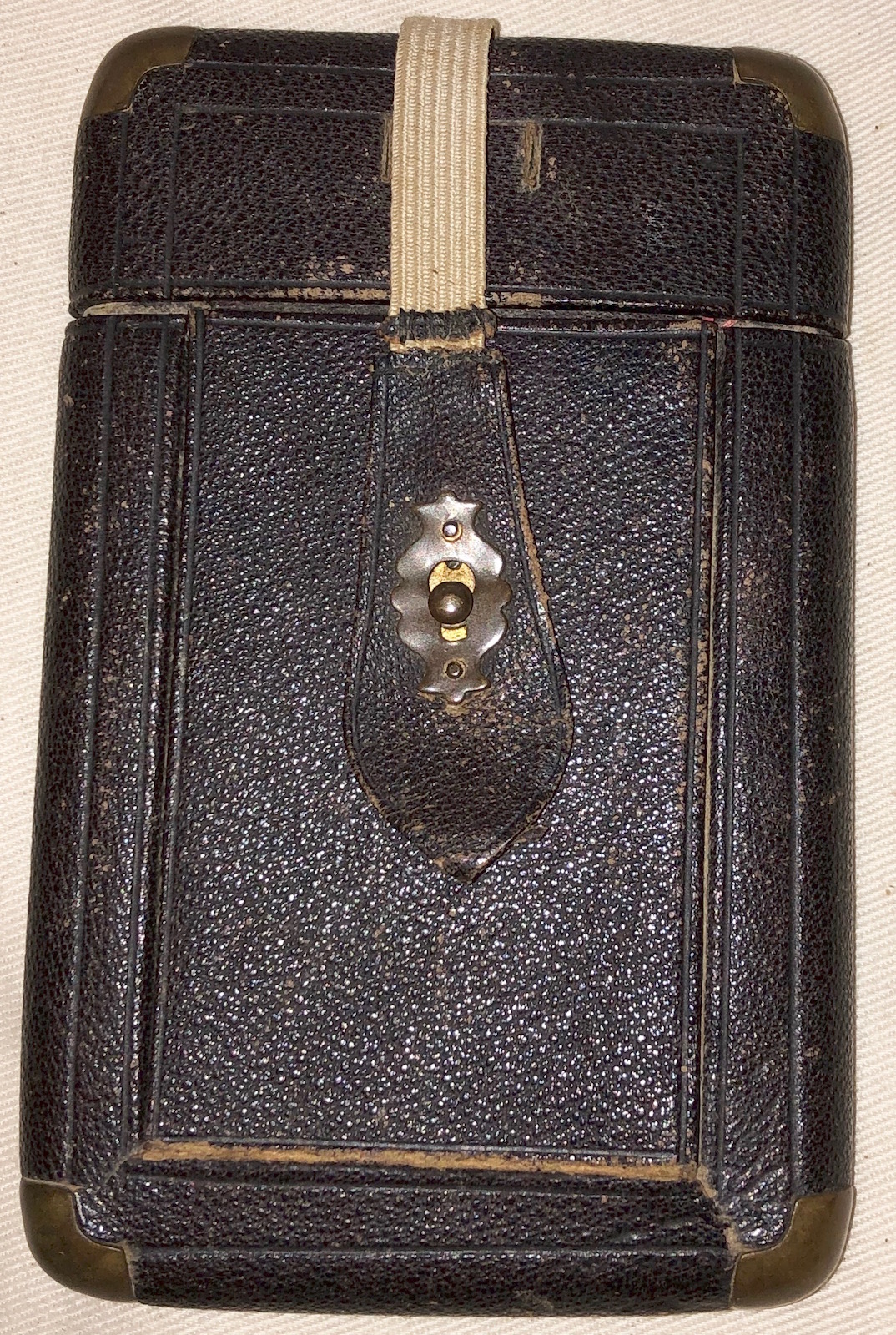

- Dimmock’s housewife / traveling writing kit in red Moroccan leather

- Dimmock’s grooming kit – includes small, silvered mirror, small scissors, grooming instruments

- Dimmock’s Confederate, extremely rare, manuscript E – engineer’s hat insignia – in a rare, round, twisted bullion

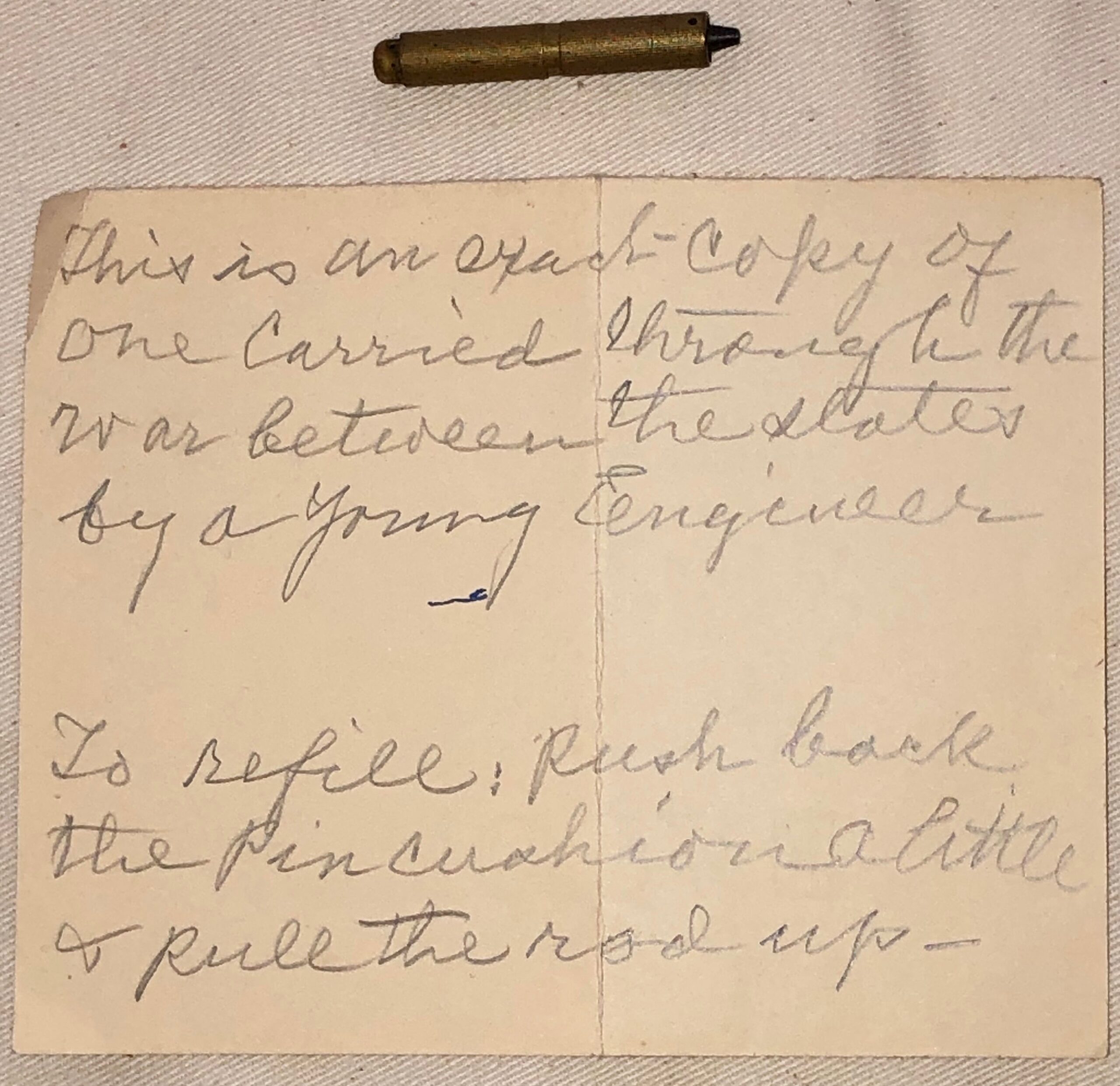

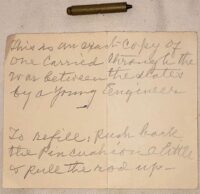

- Dimmock’s mechanical pencil – brass, functional

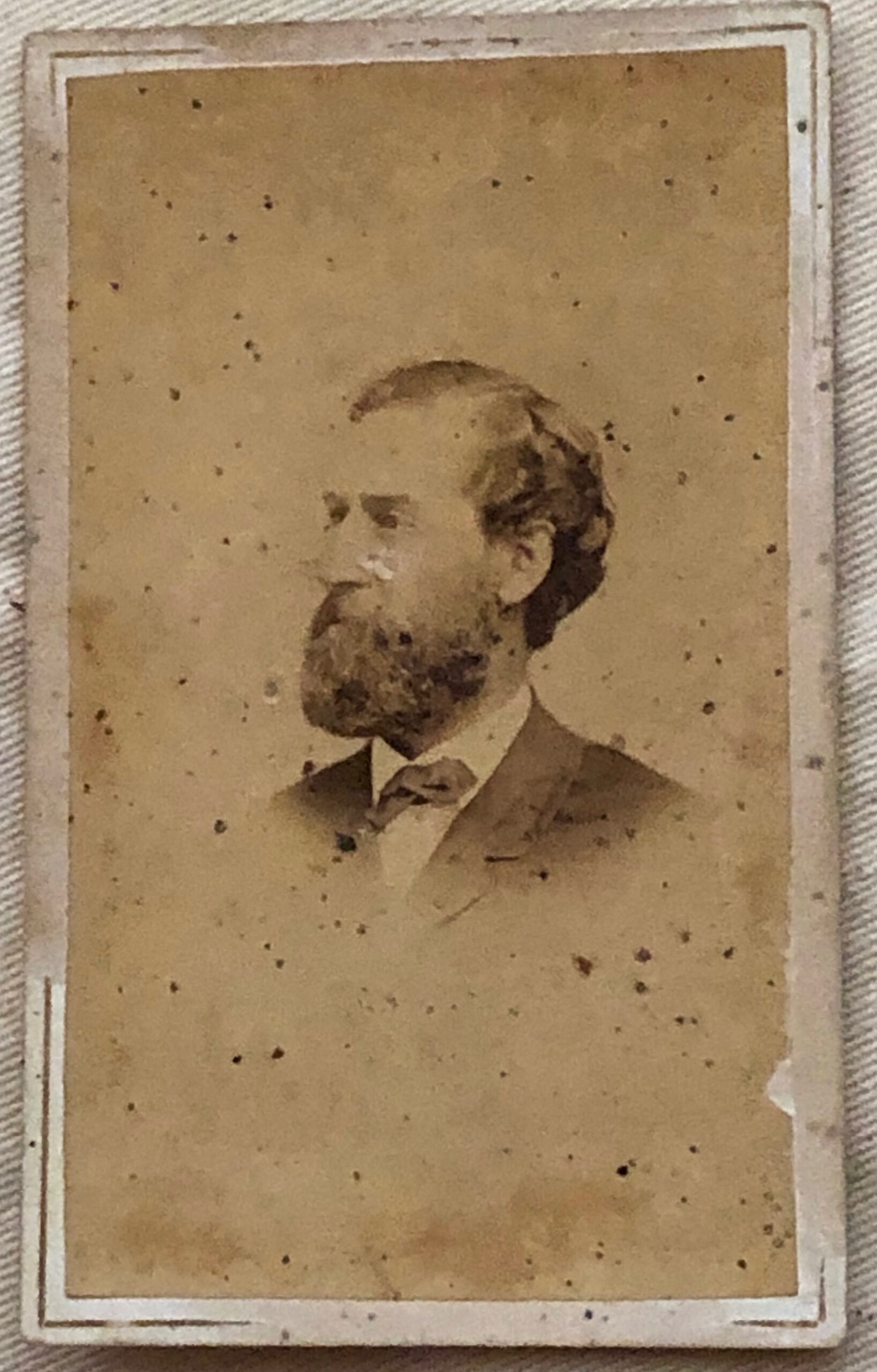

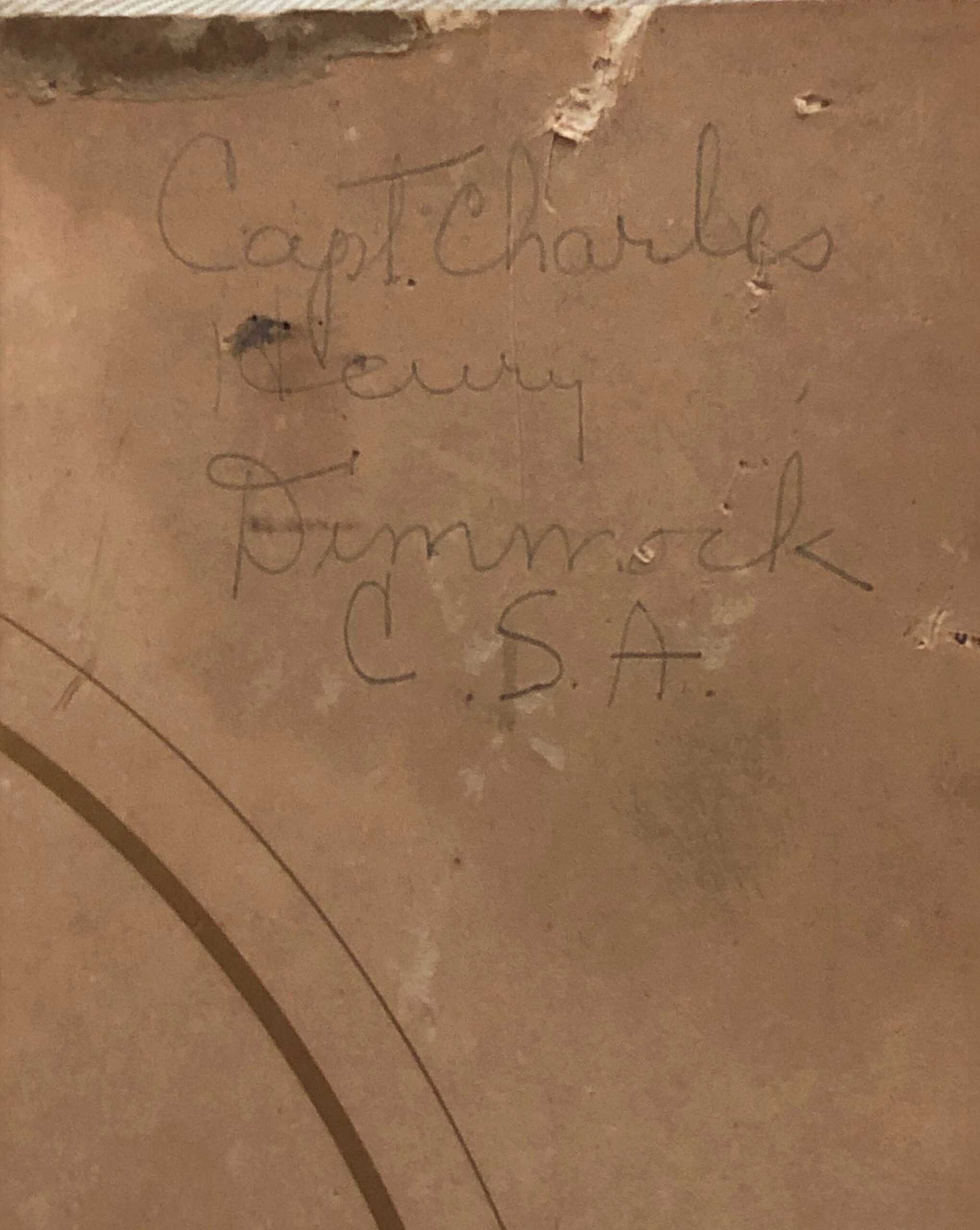

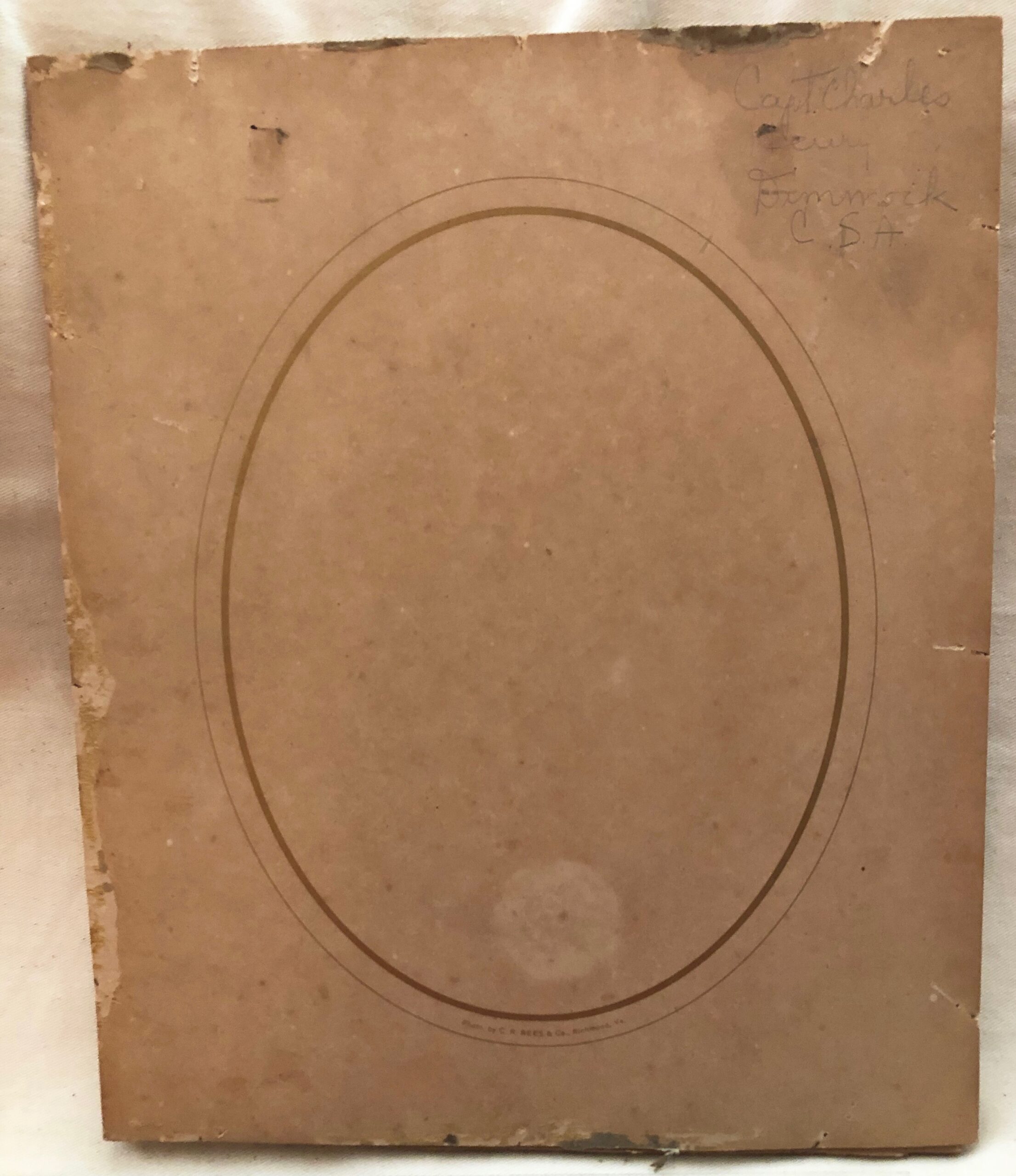

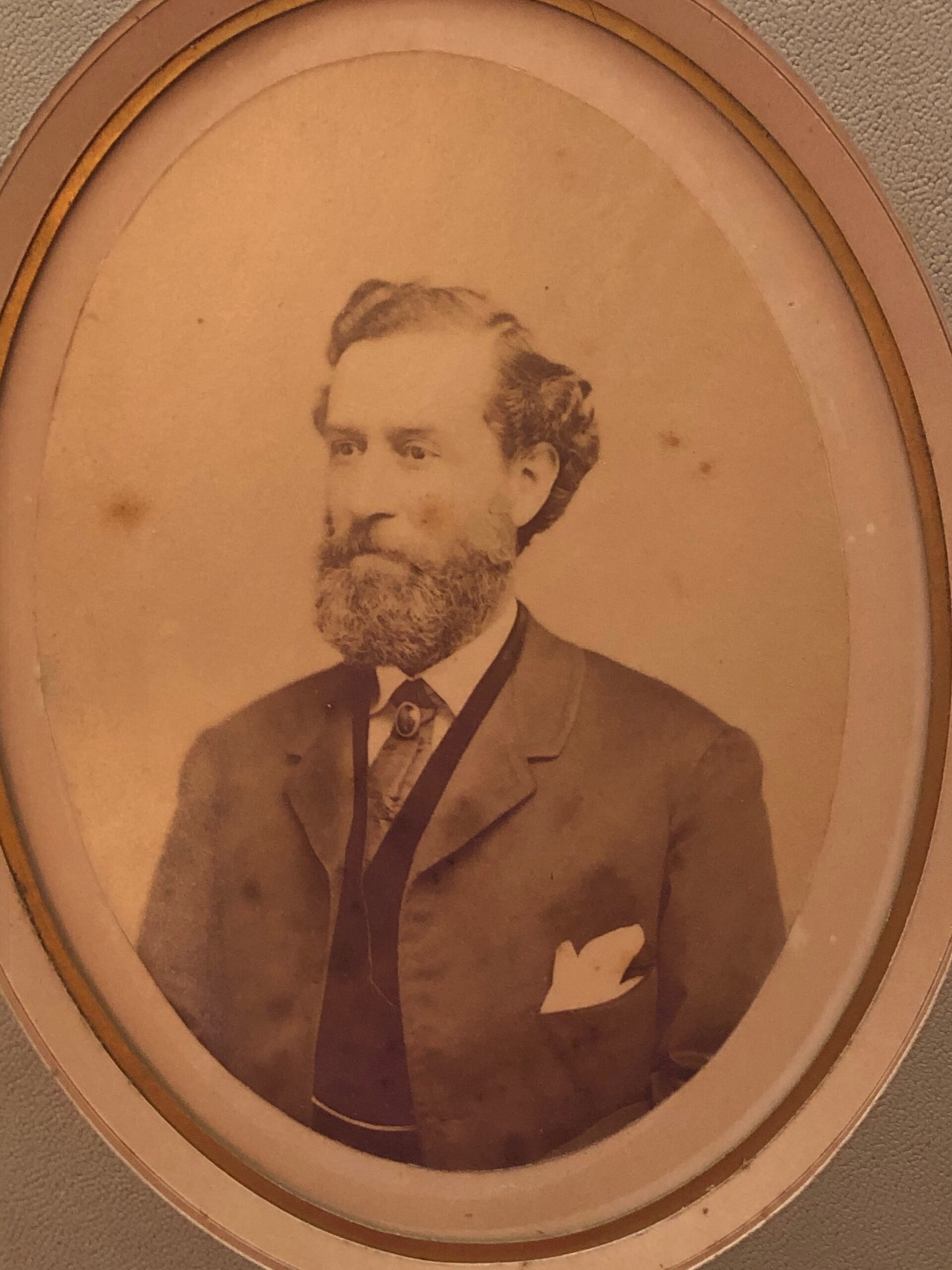

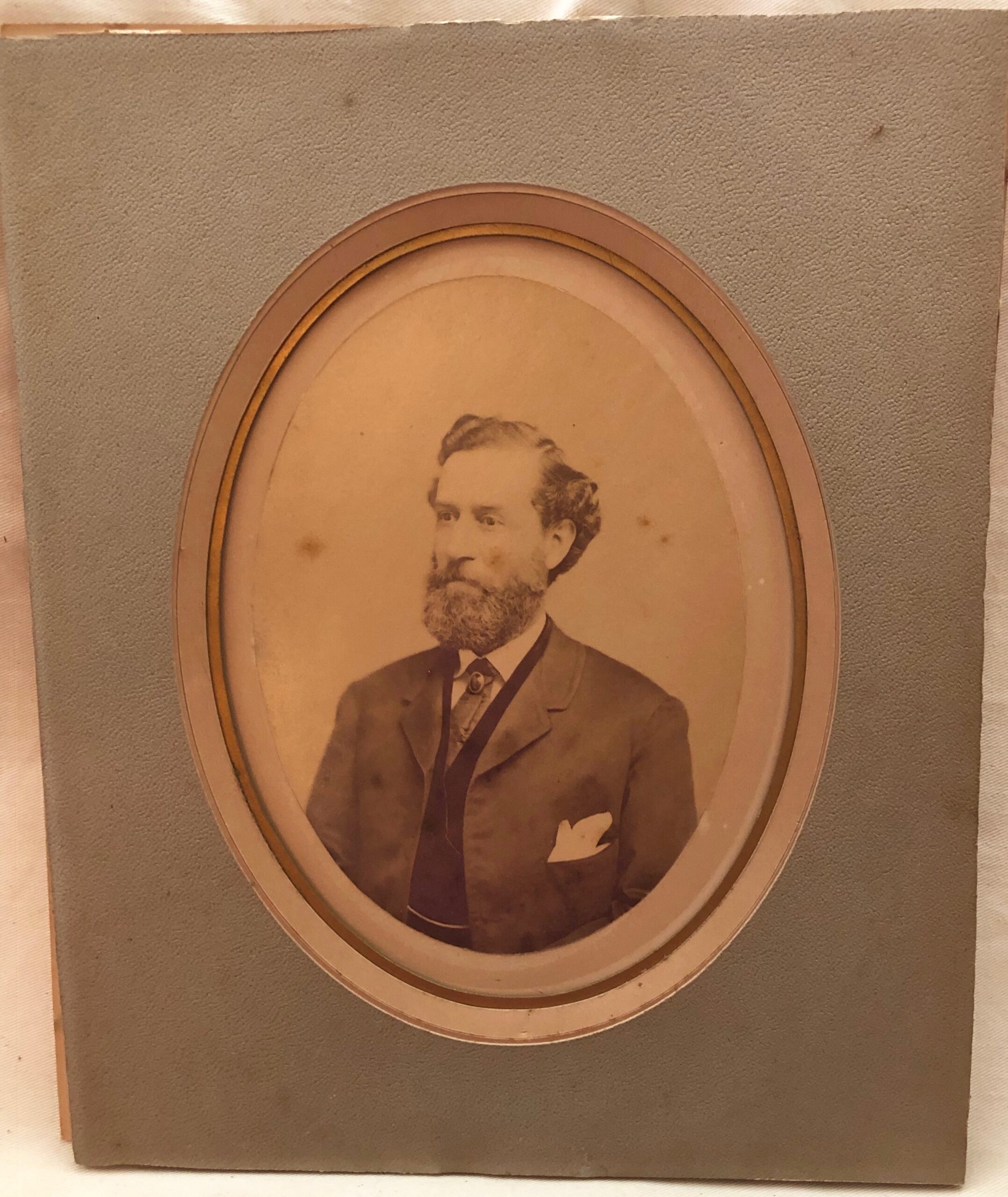

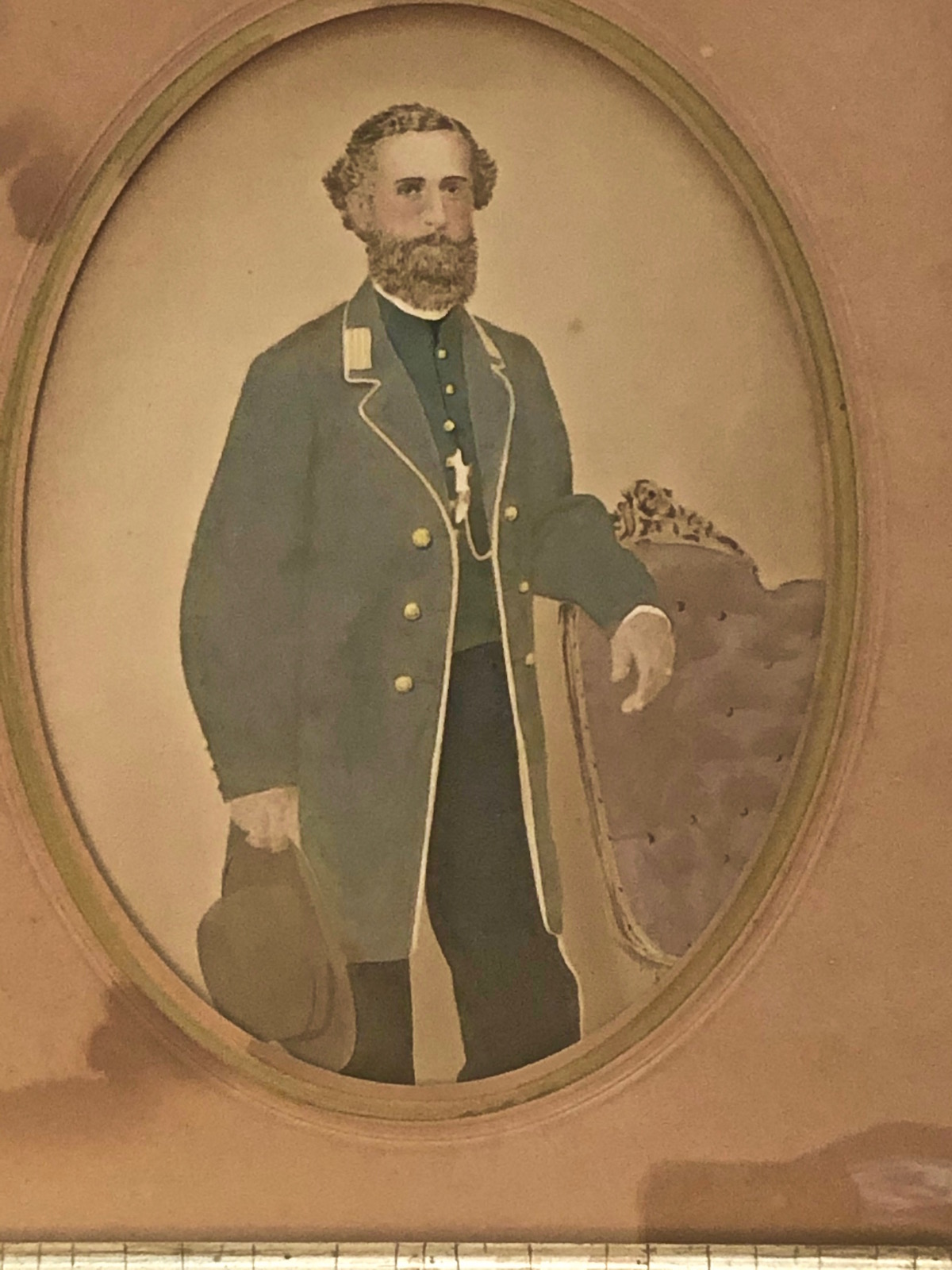

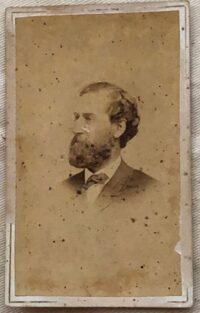

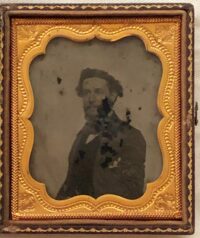

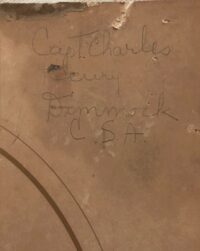

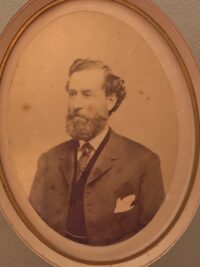

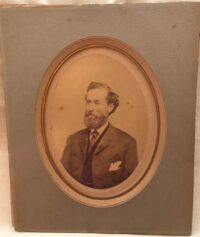

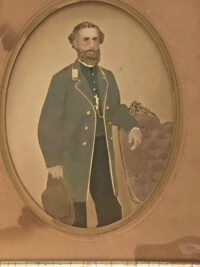

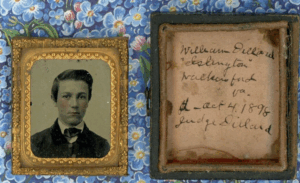

- Black and white albumen image of Capt. Dimmock in period frame

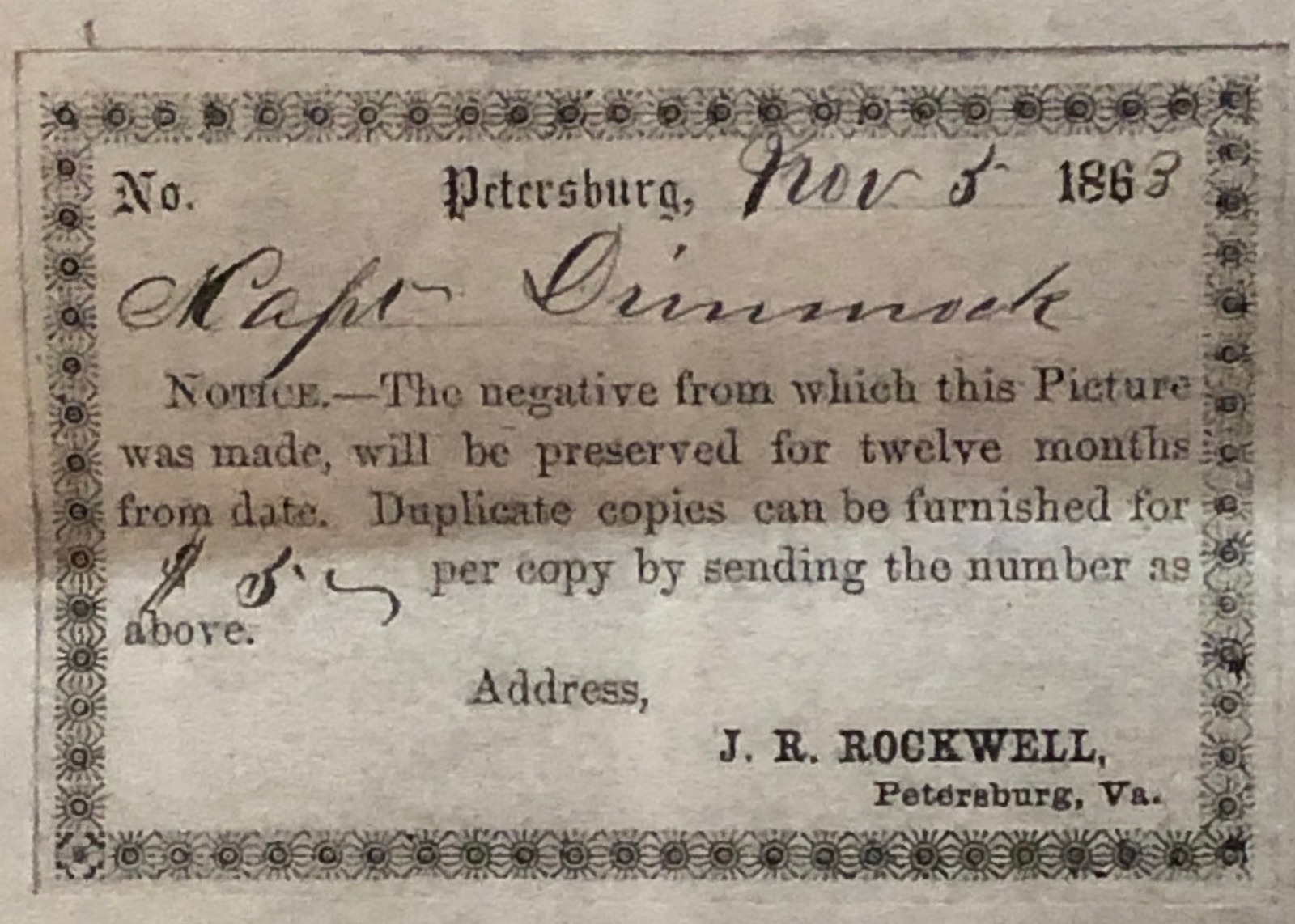

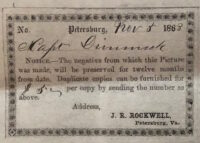

- Artist tinted albumen image of Capt. Dimmock; framed with the noted, Petersburg photographer, J.R. Rockwell’s label affixed to the back of the image – Dimmock mentions this image in a wartime letter to his wife – he notes that he had his draughtsman tint the image, in the letter

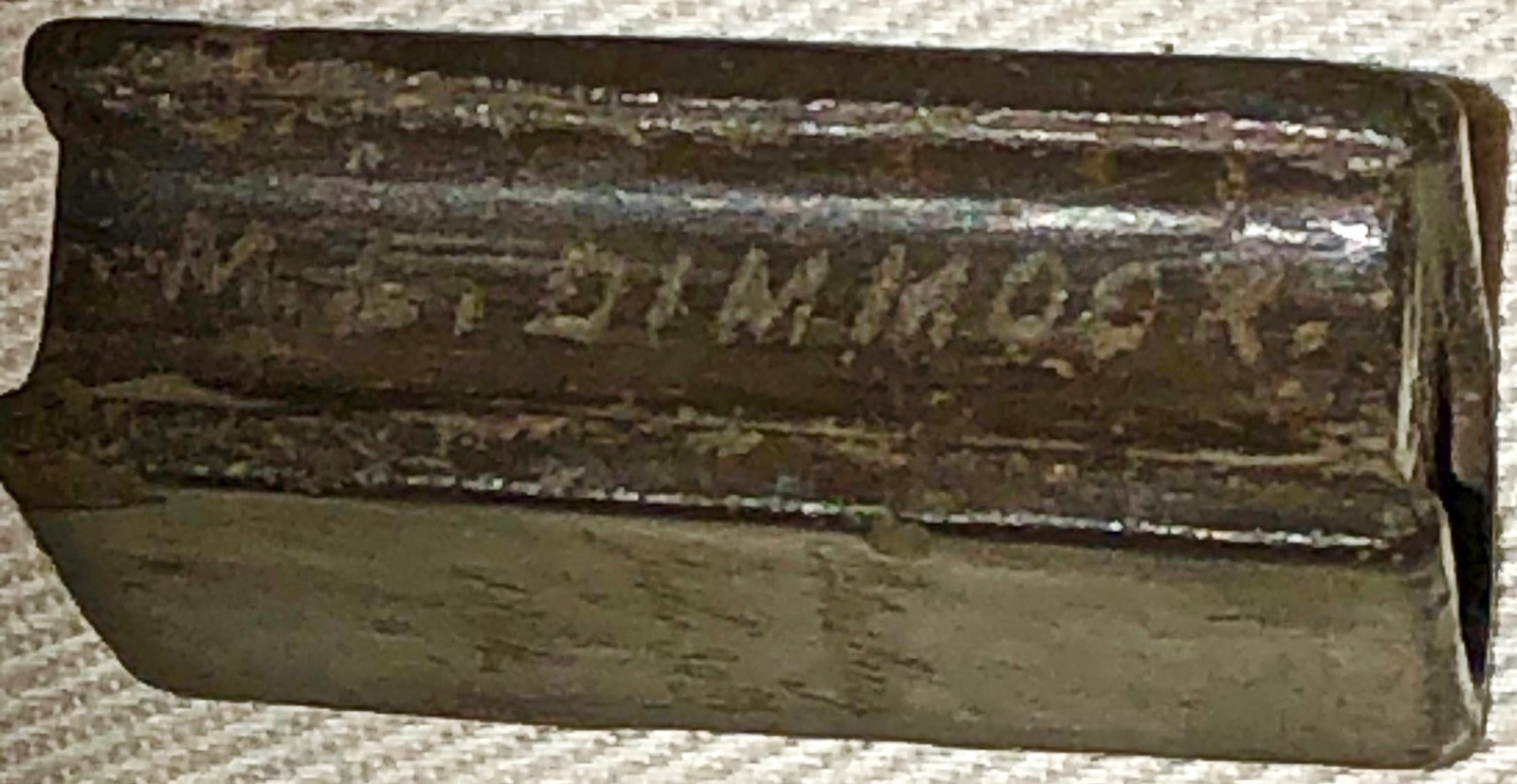

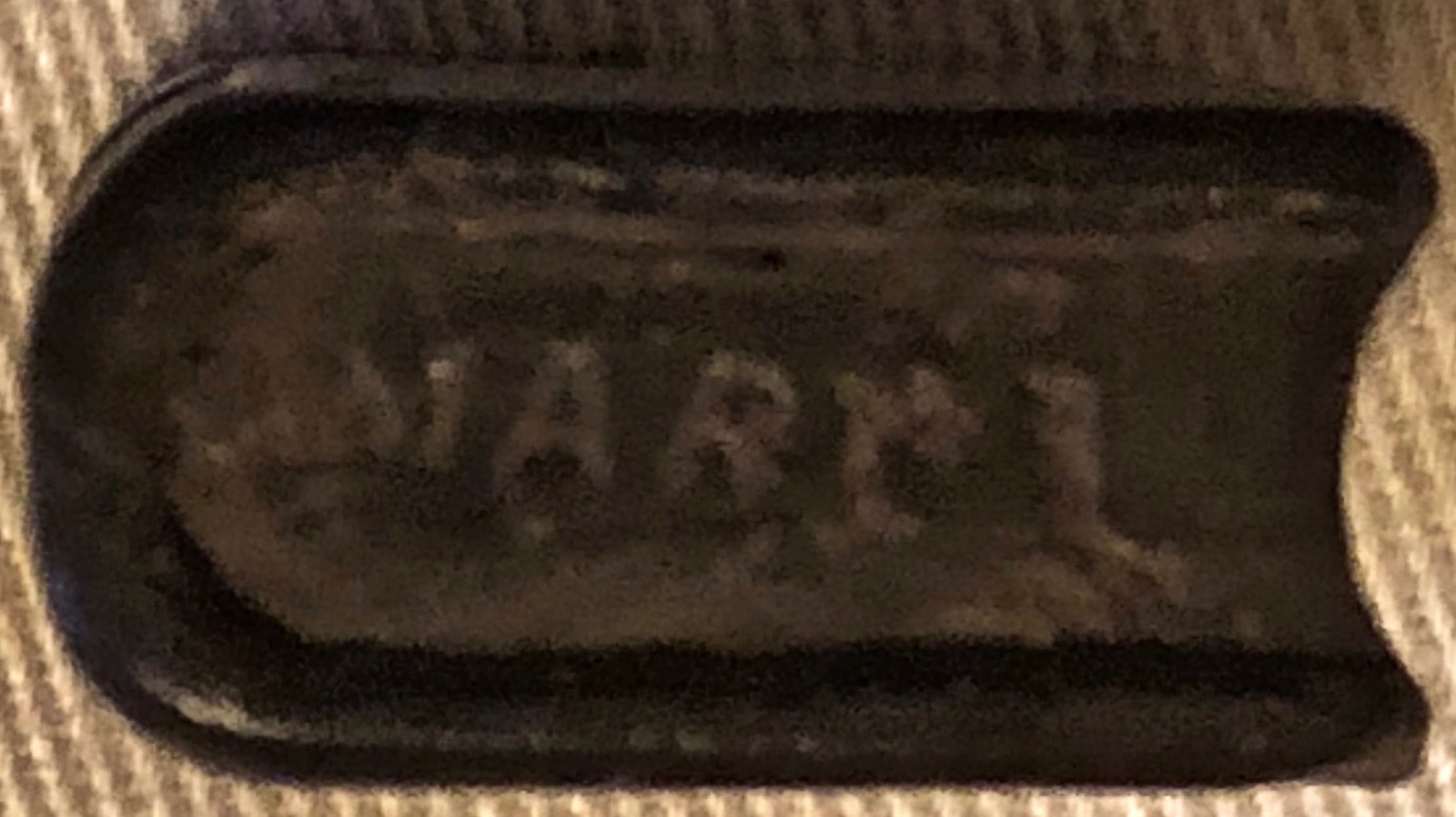

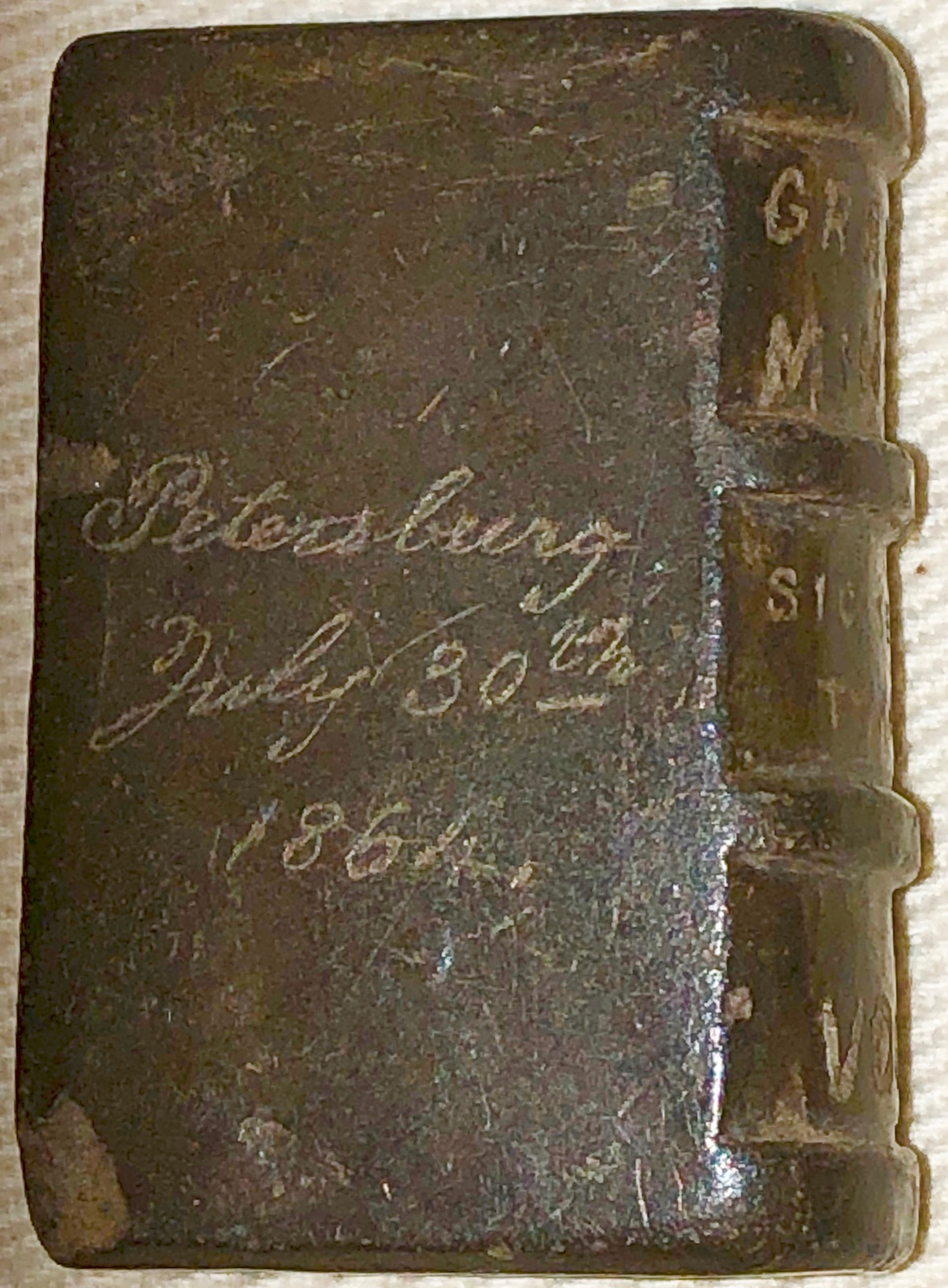

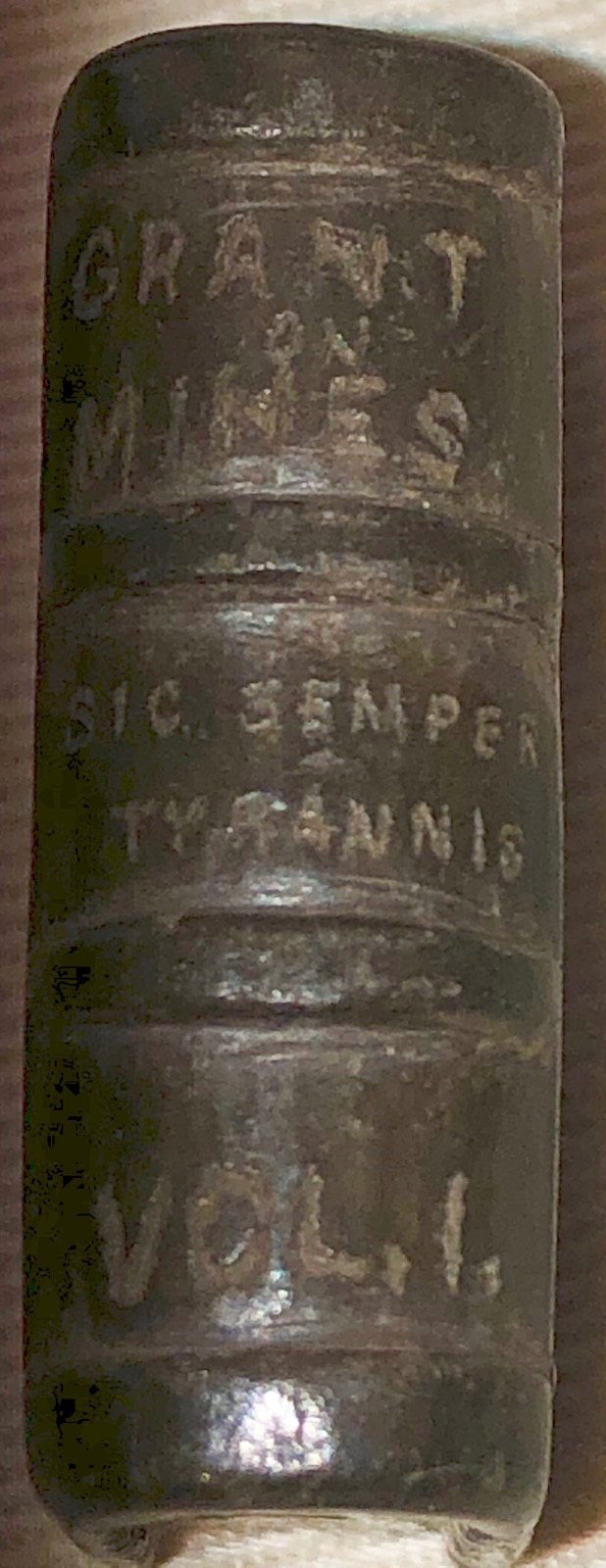

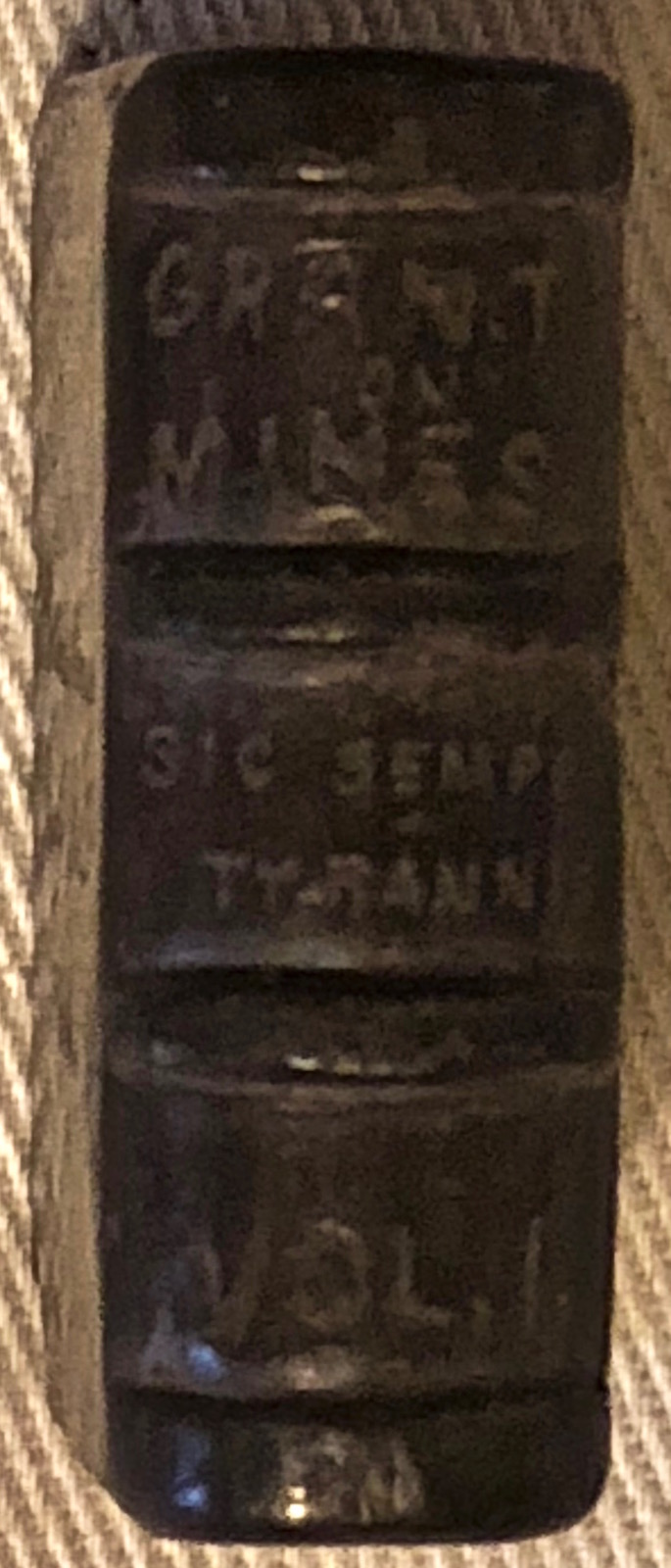

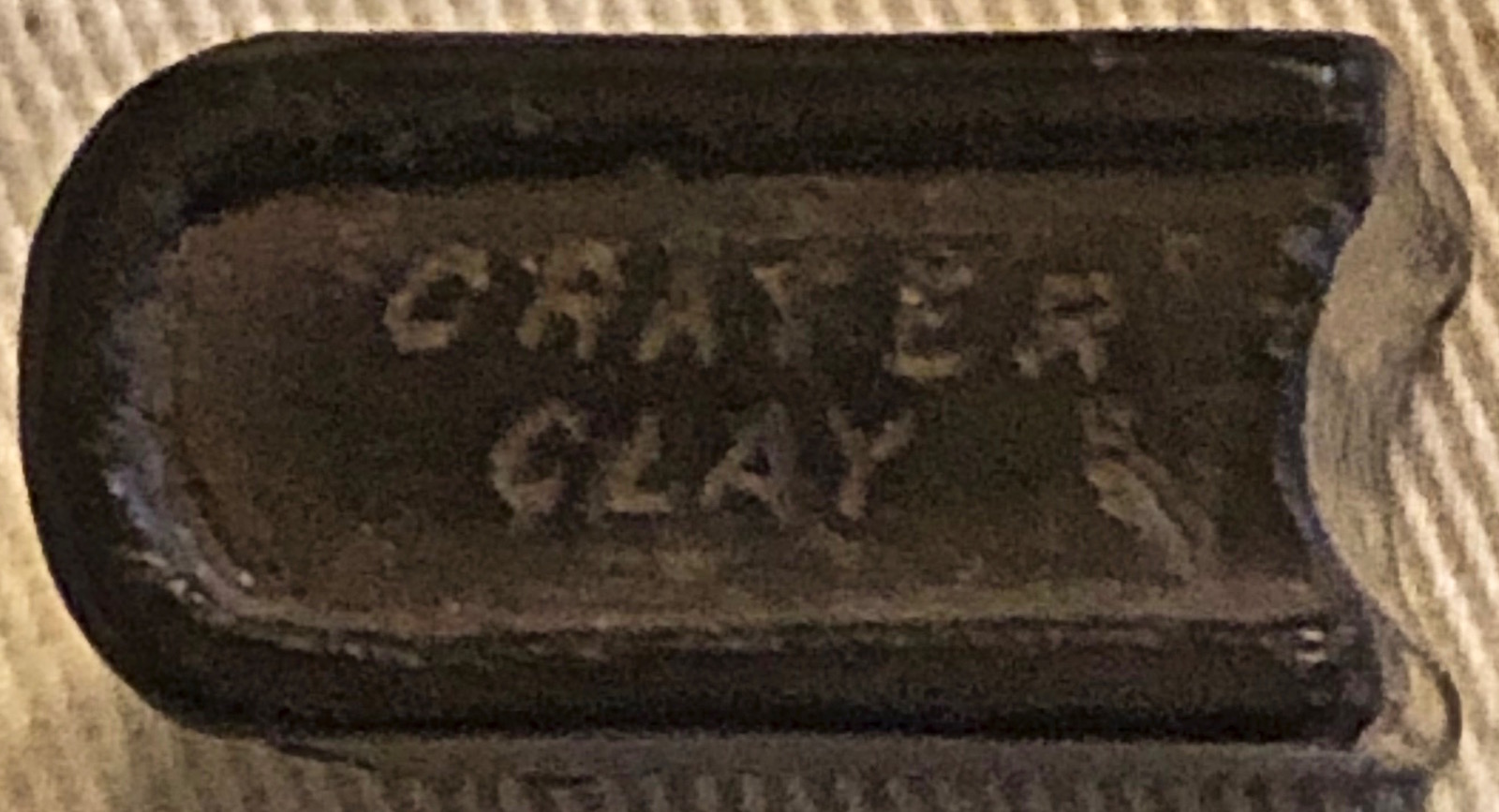

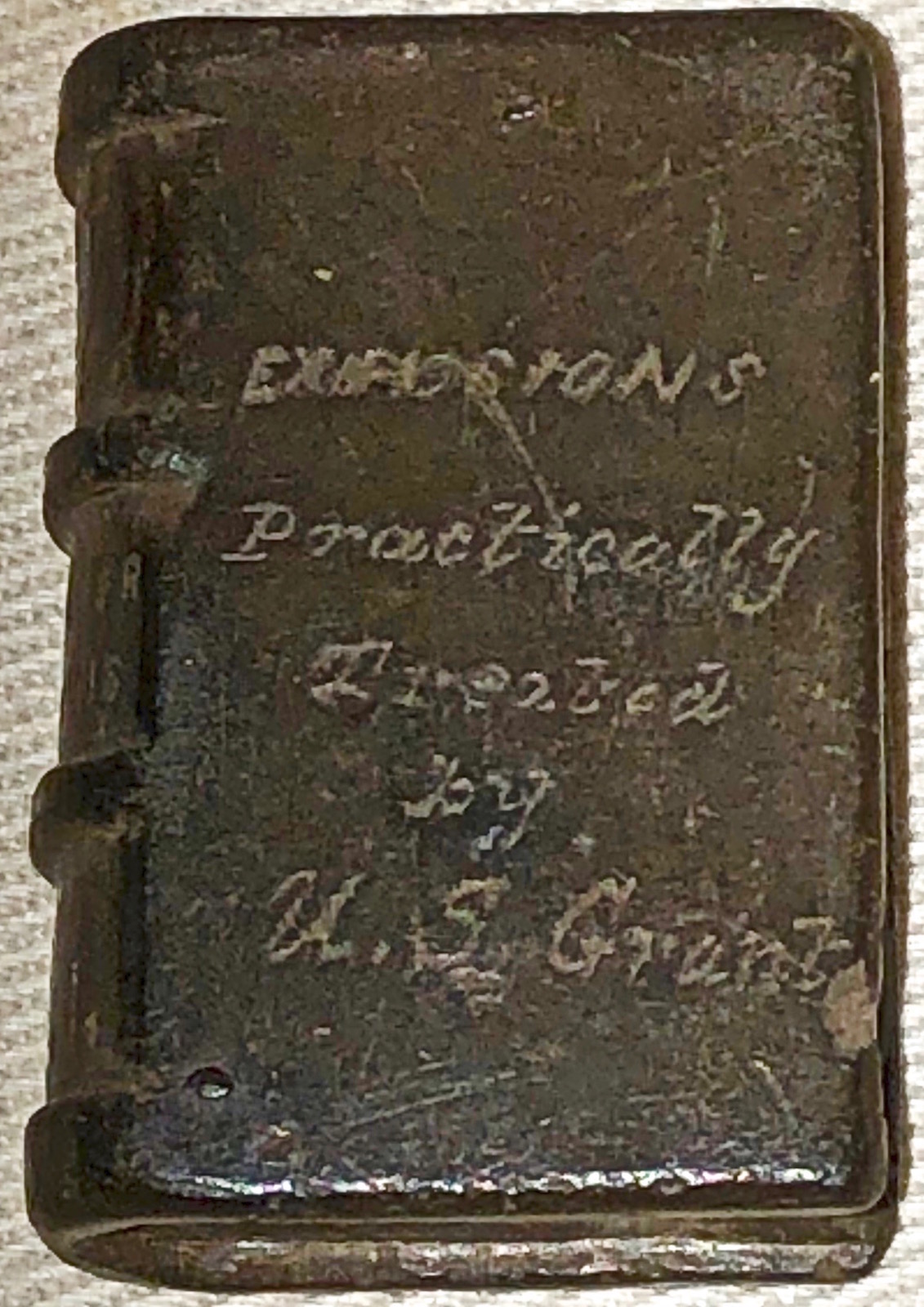

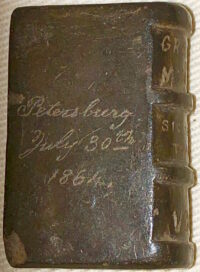

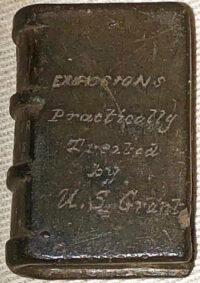

- Fired clay (from the Crater) fashioned into a miniature book that exhibits multiple engraved statements and the names of his wife and young daughter (born the day before the mine explosion); the clay is made from a finely crafted bit of ejected by the mine explosion, on July 30, 1864

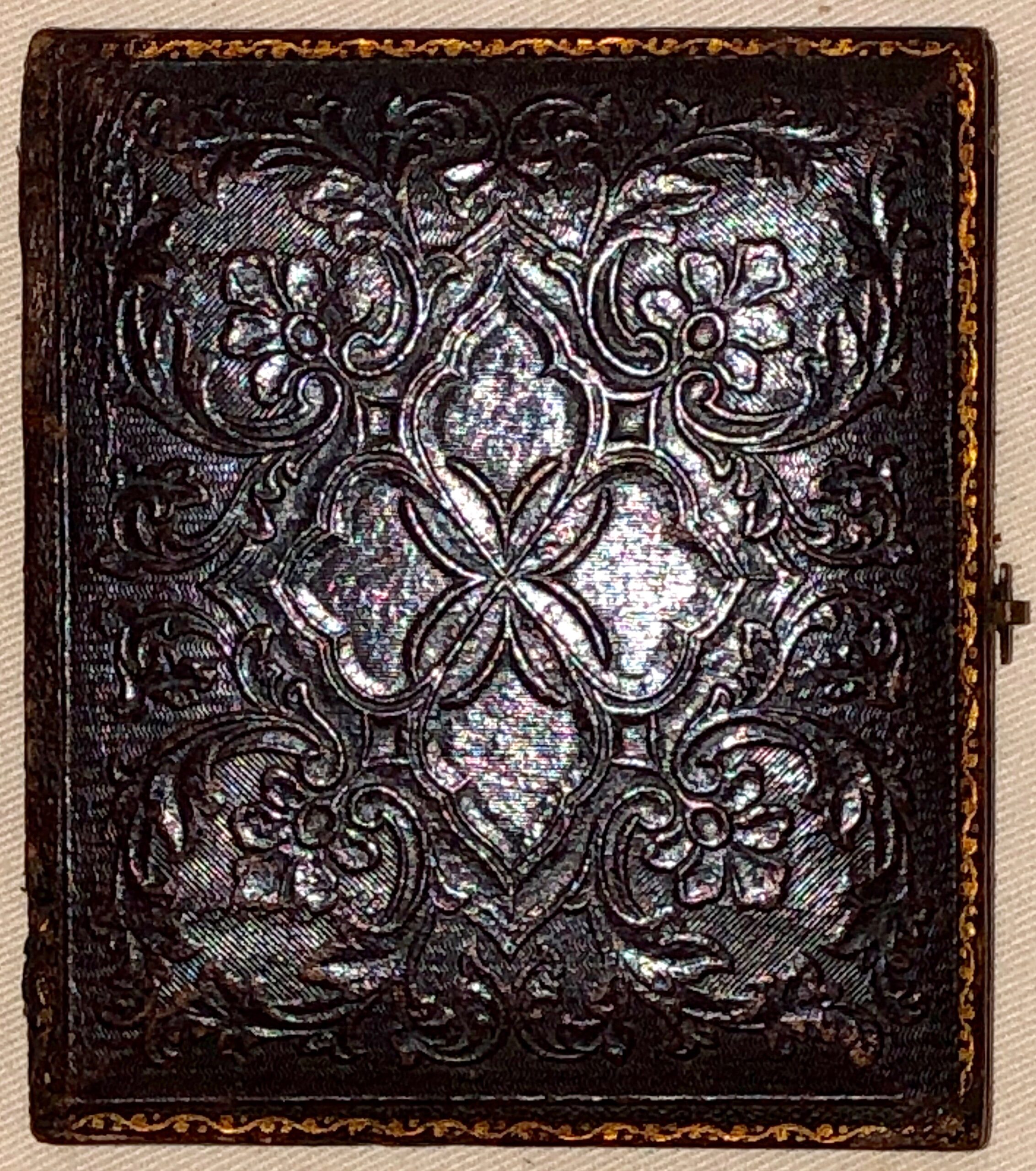

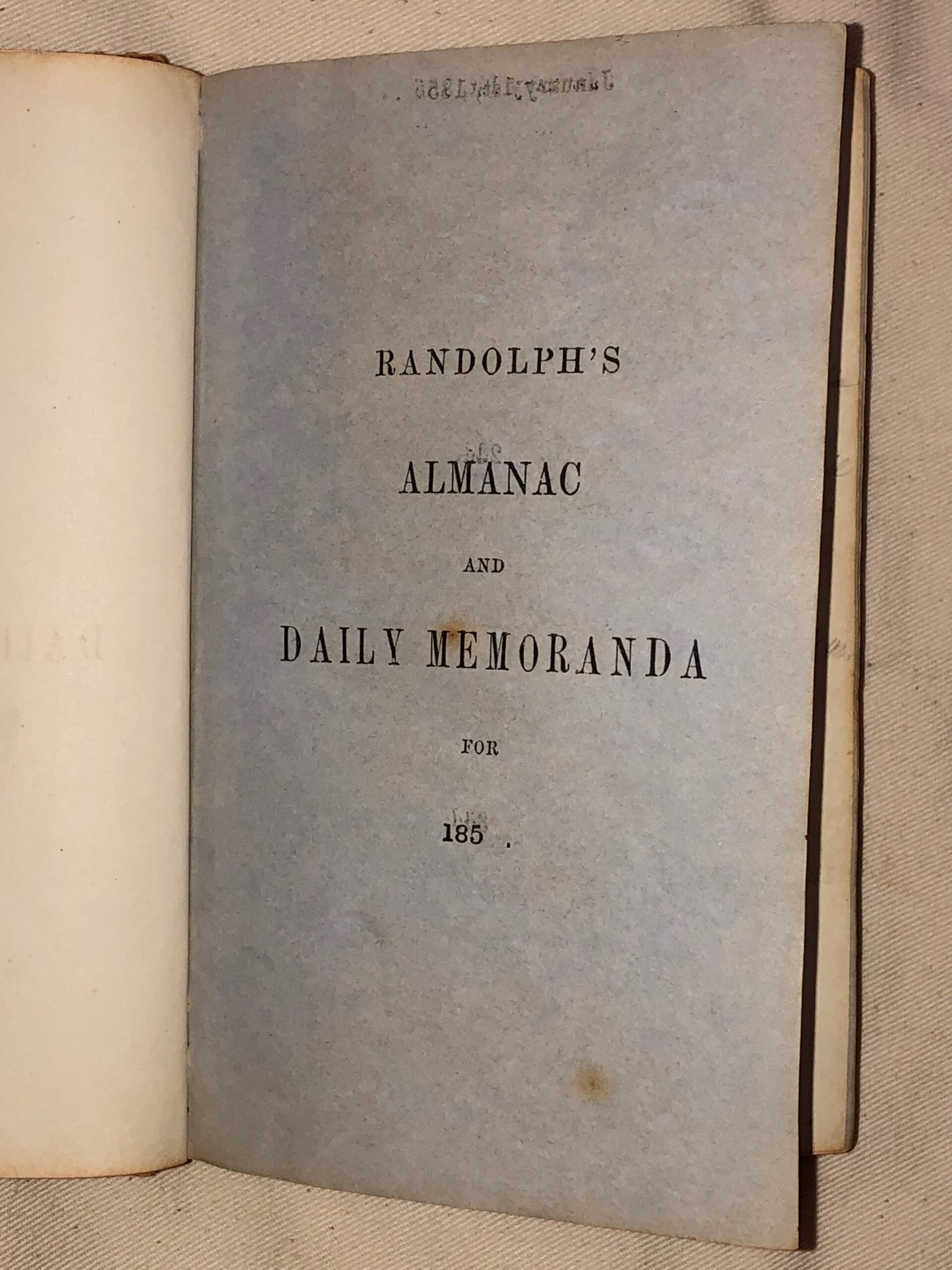

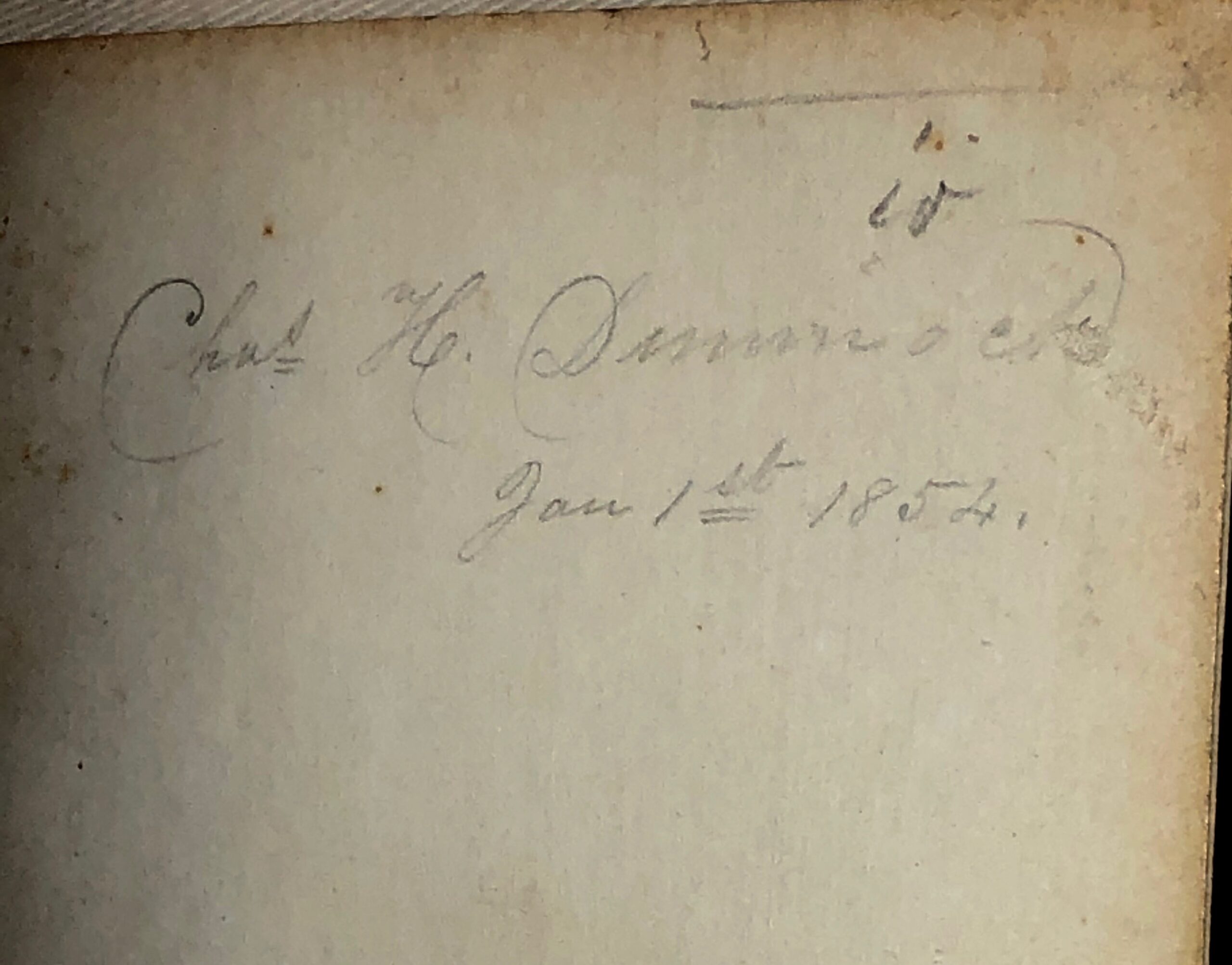

- Pre-CW journal of Capt. Dimmock with his poetry – hand written entries by Dimmock in the 1850s

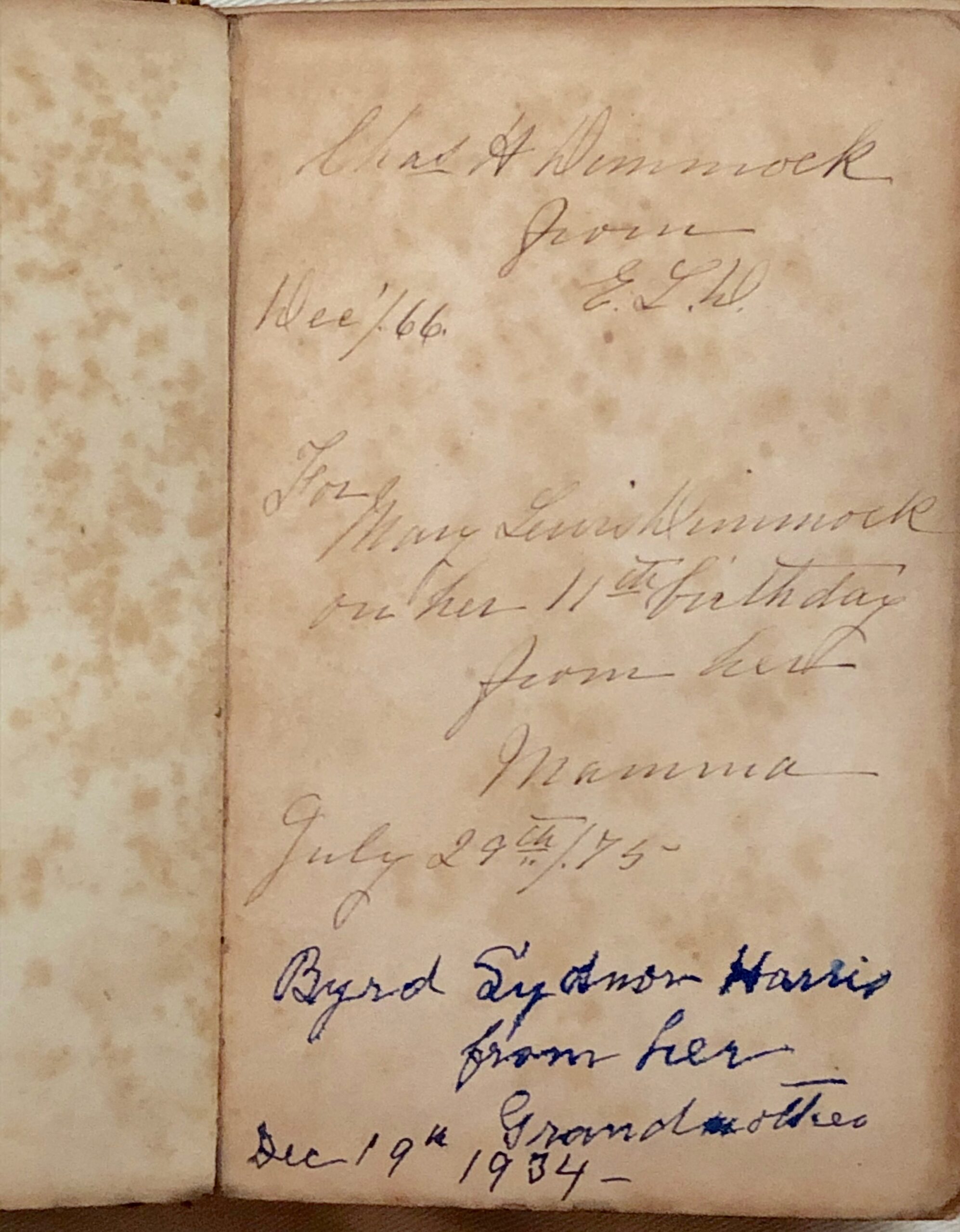

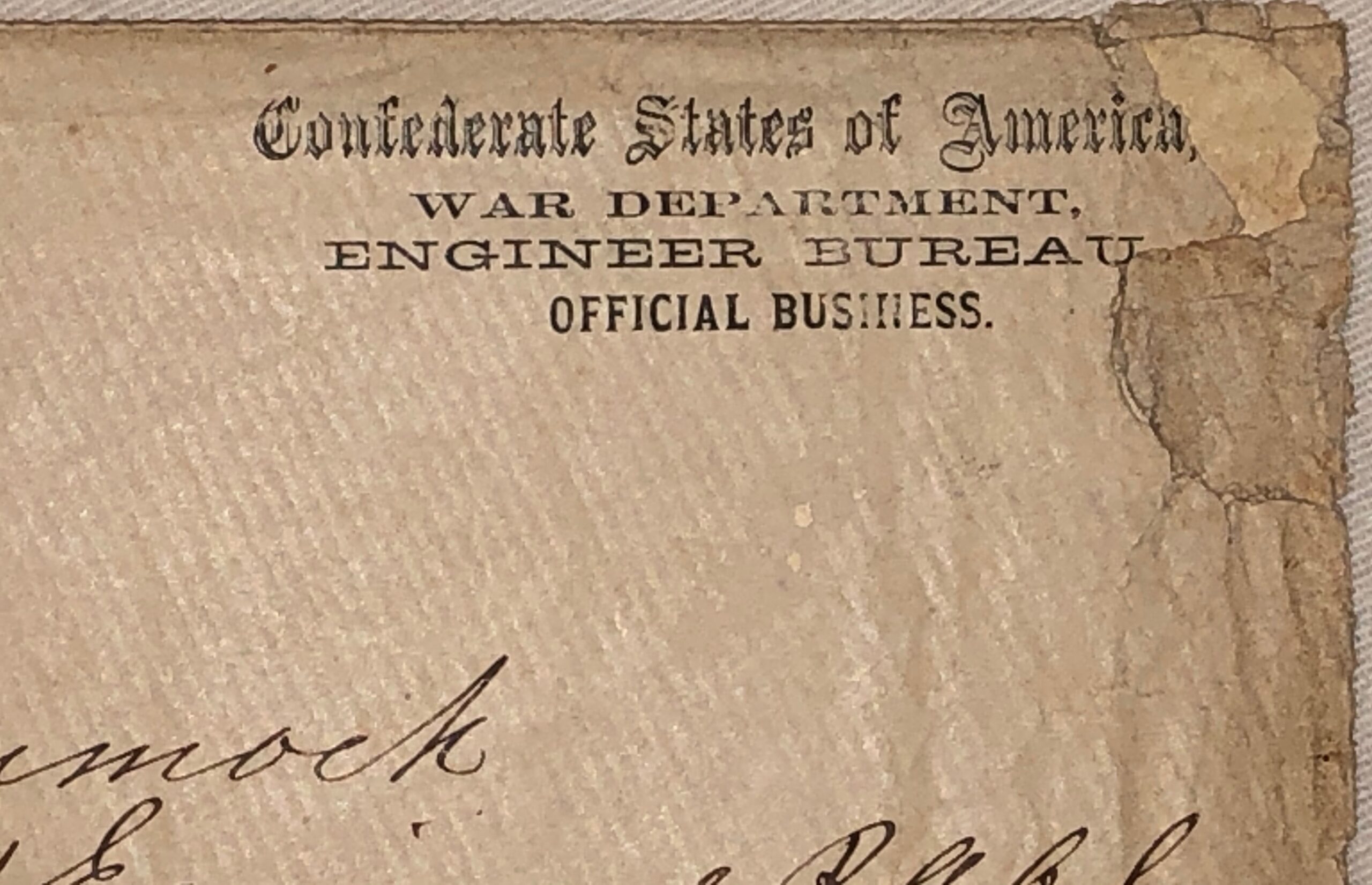

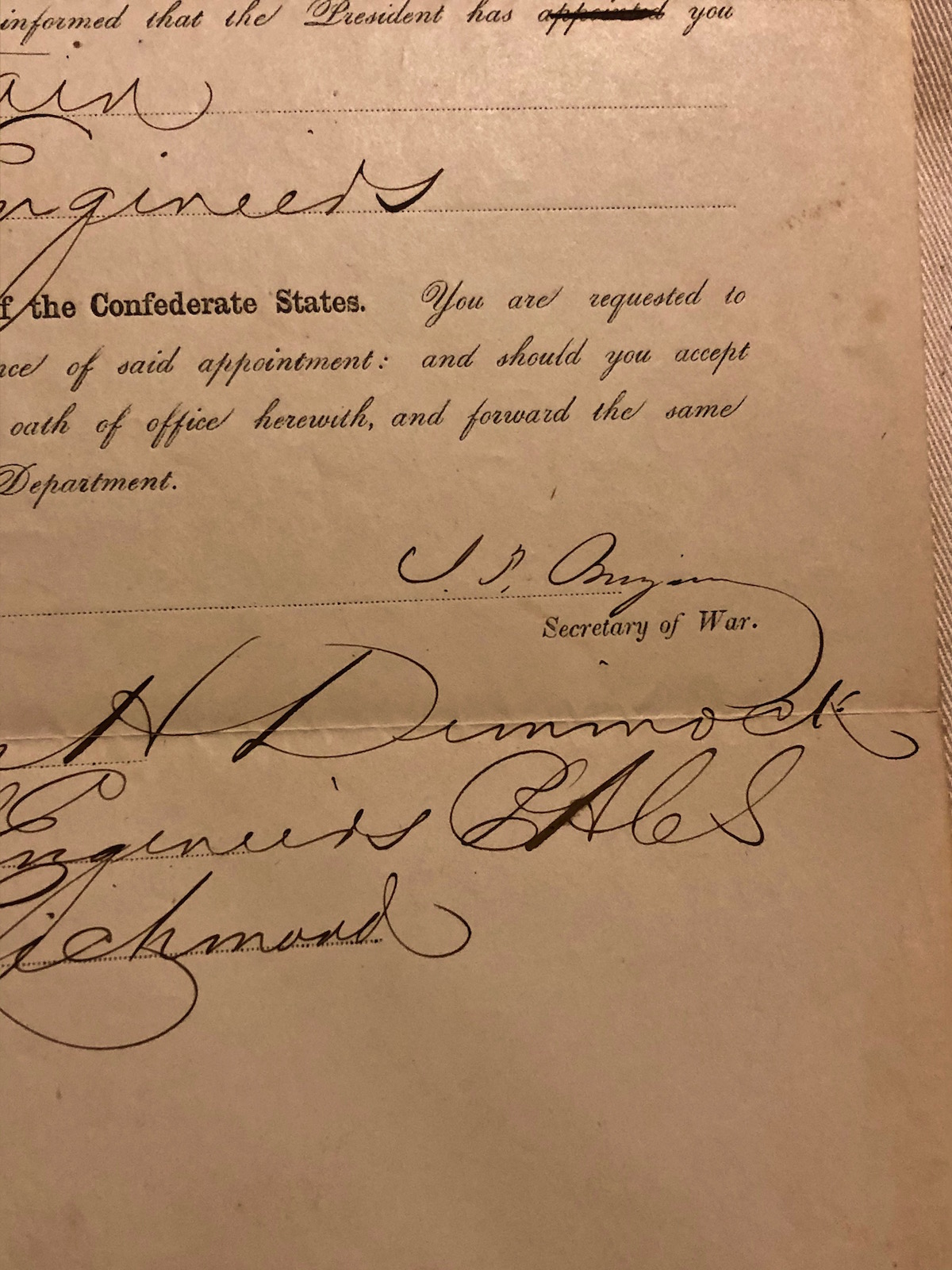

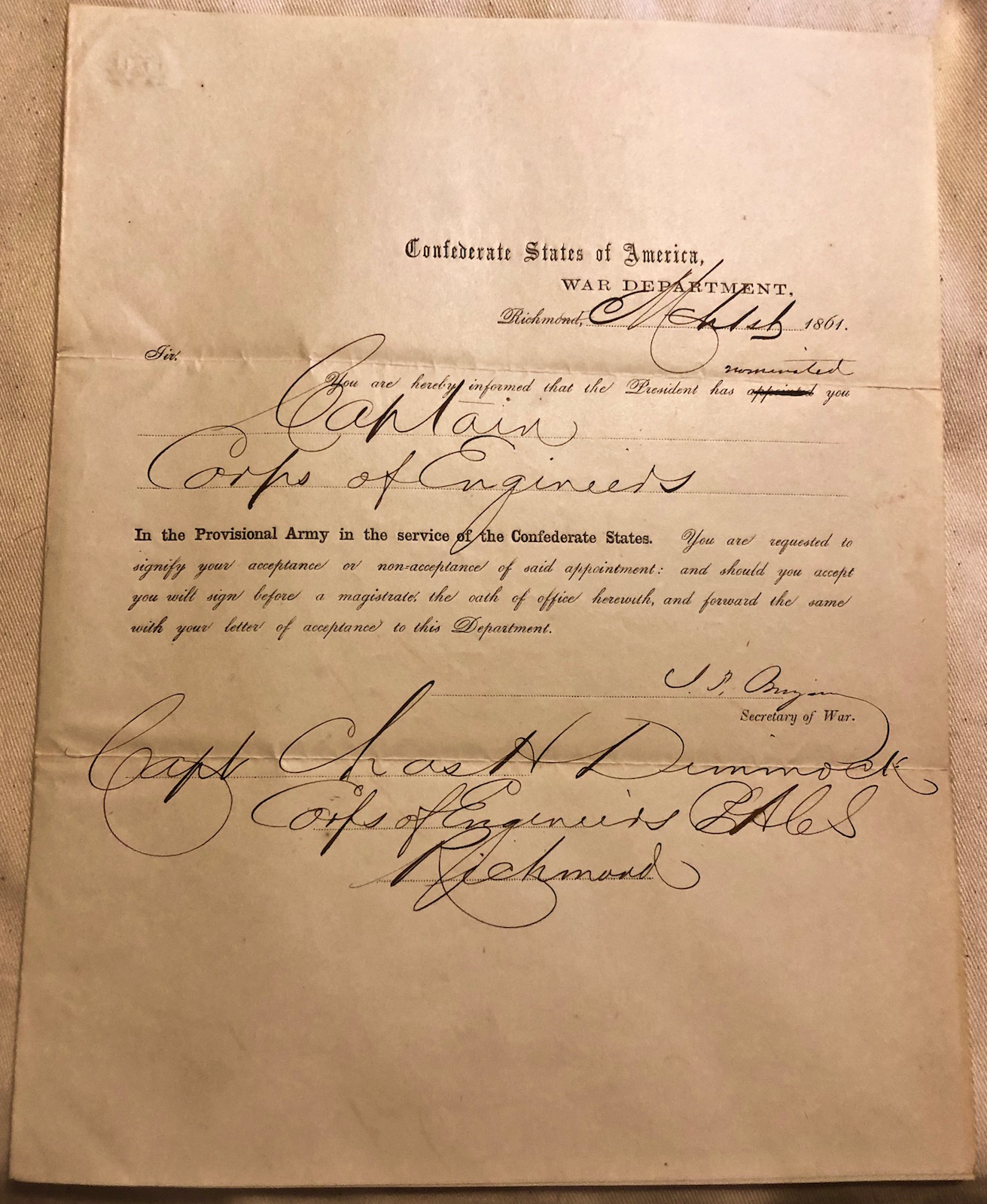

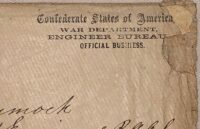

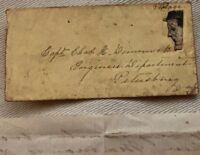

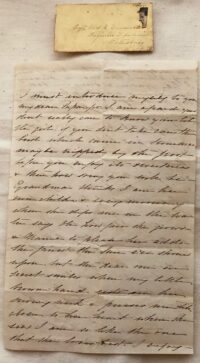

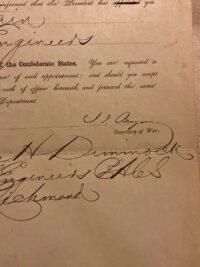

- Dimmock’s Confederate commission assigning him to the CS Engineers, signed by Judah P. Benjamin, then Confederate Secretary of War, with the original cover from CS Engineer Department

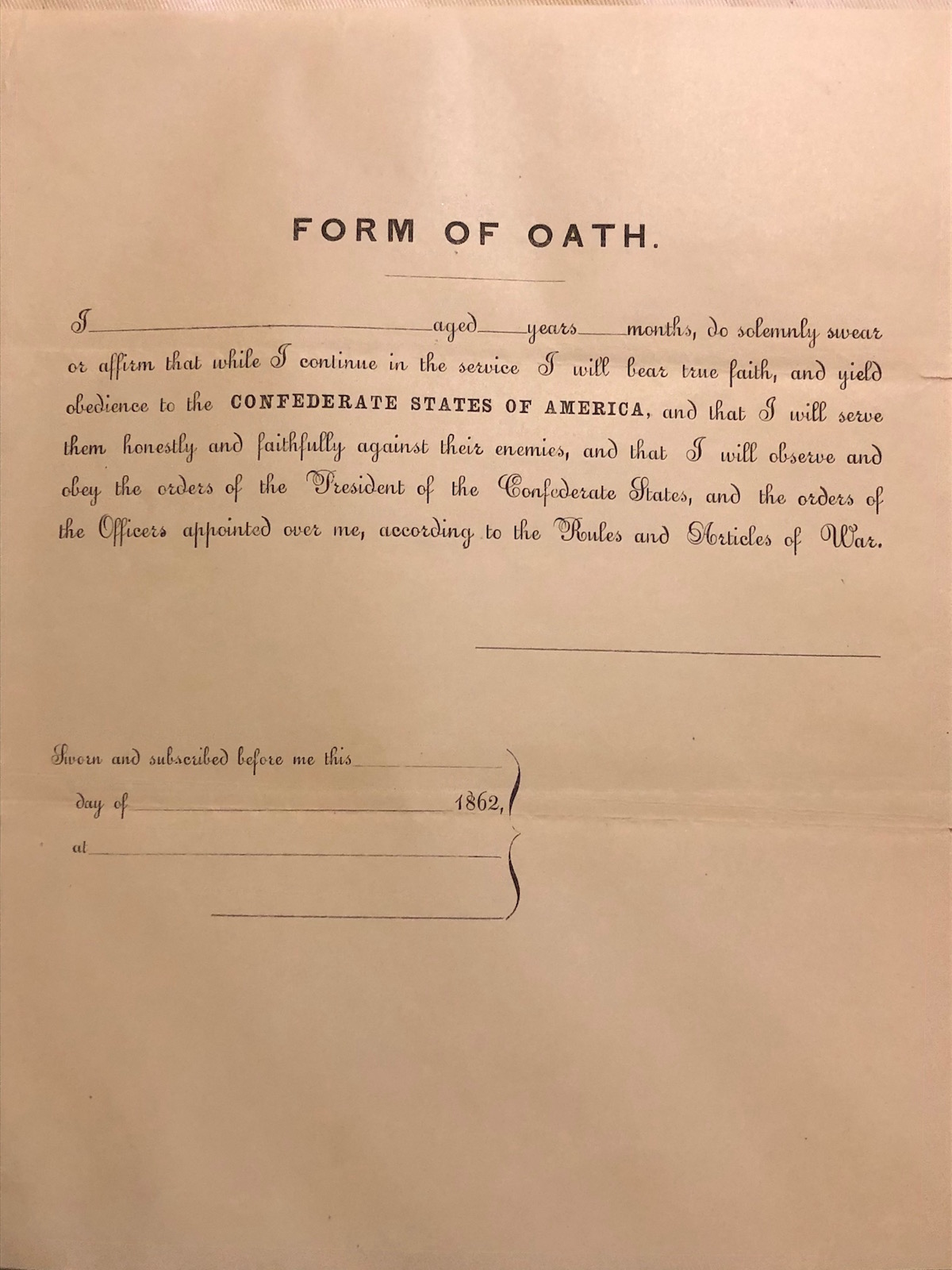

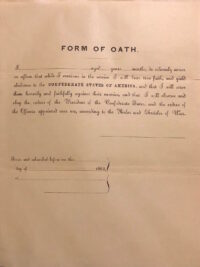

- Dimmock’s blank oath of allegiance to the Confederacy

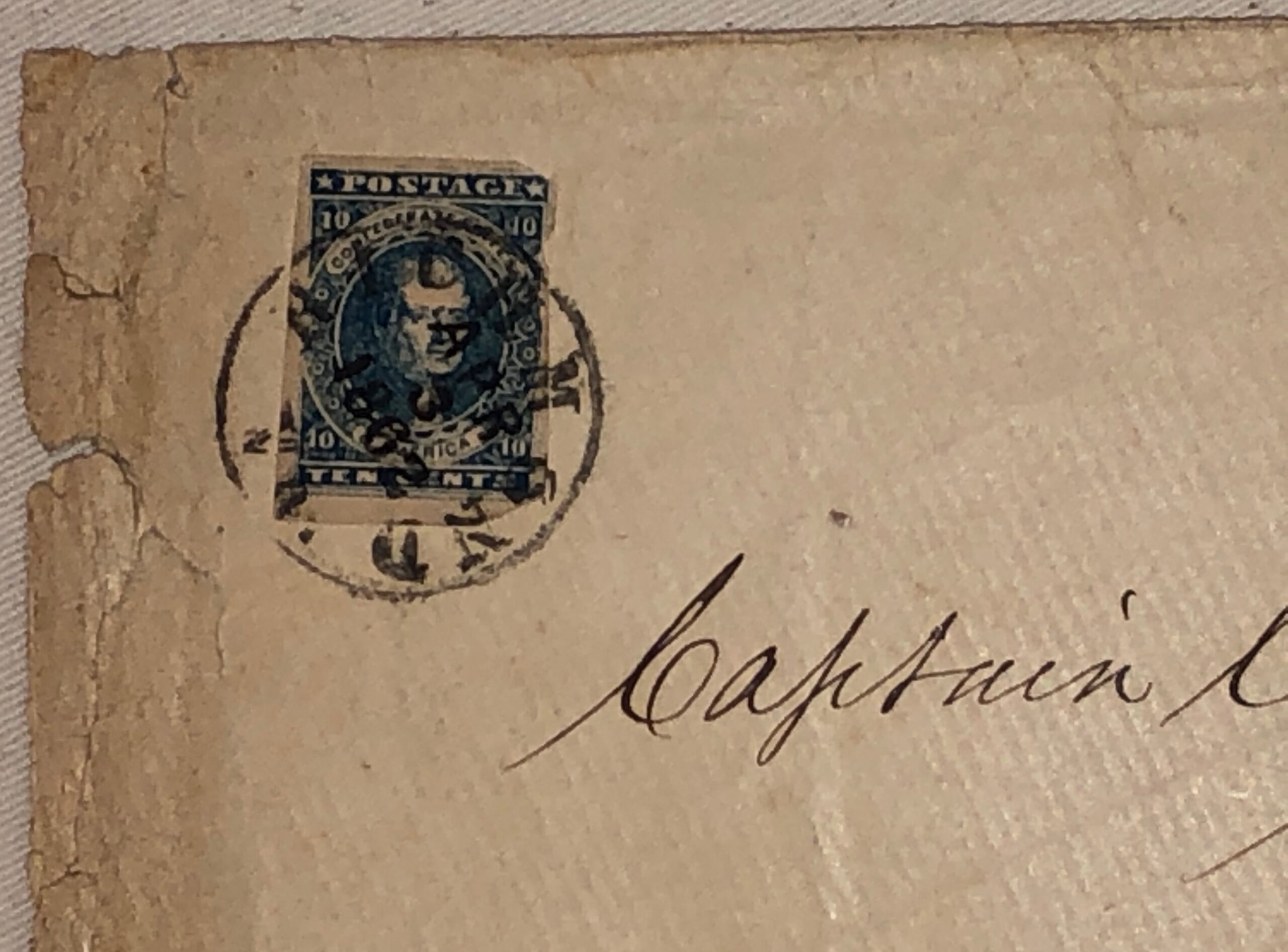

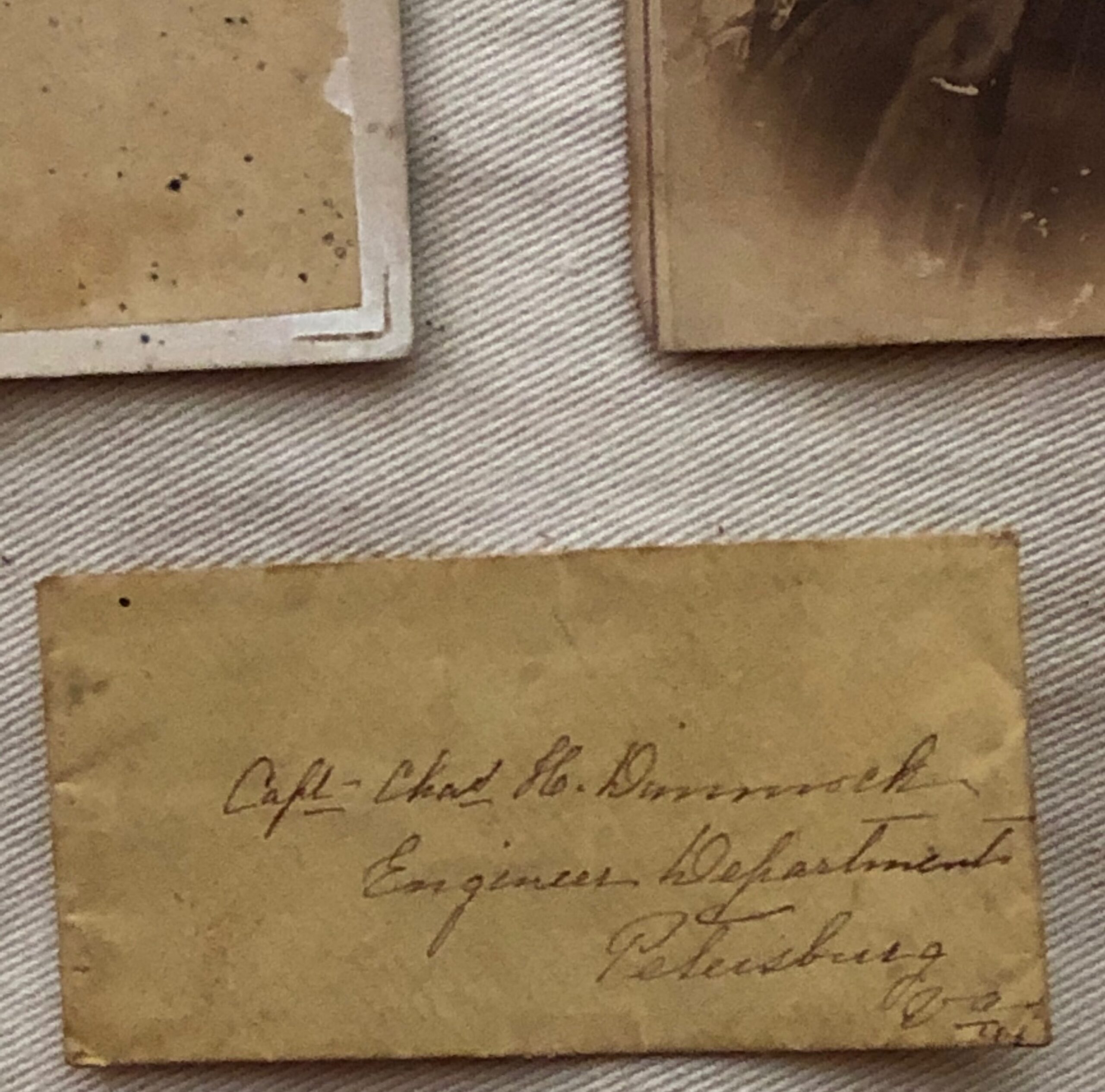

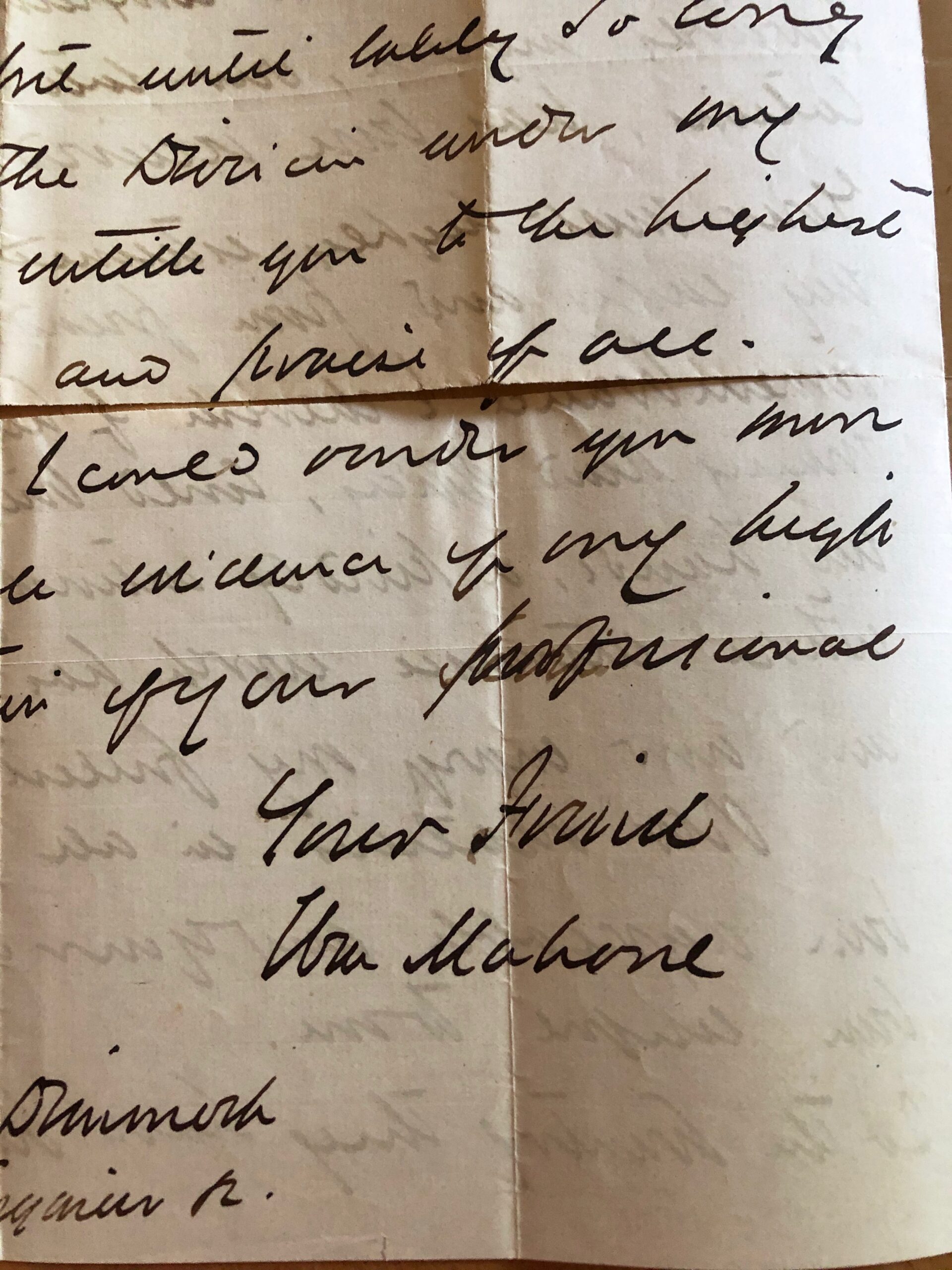

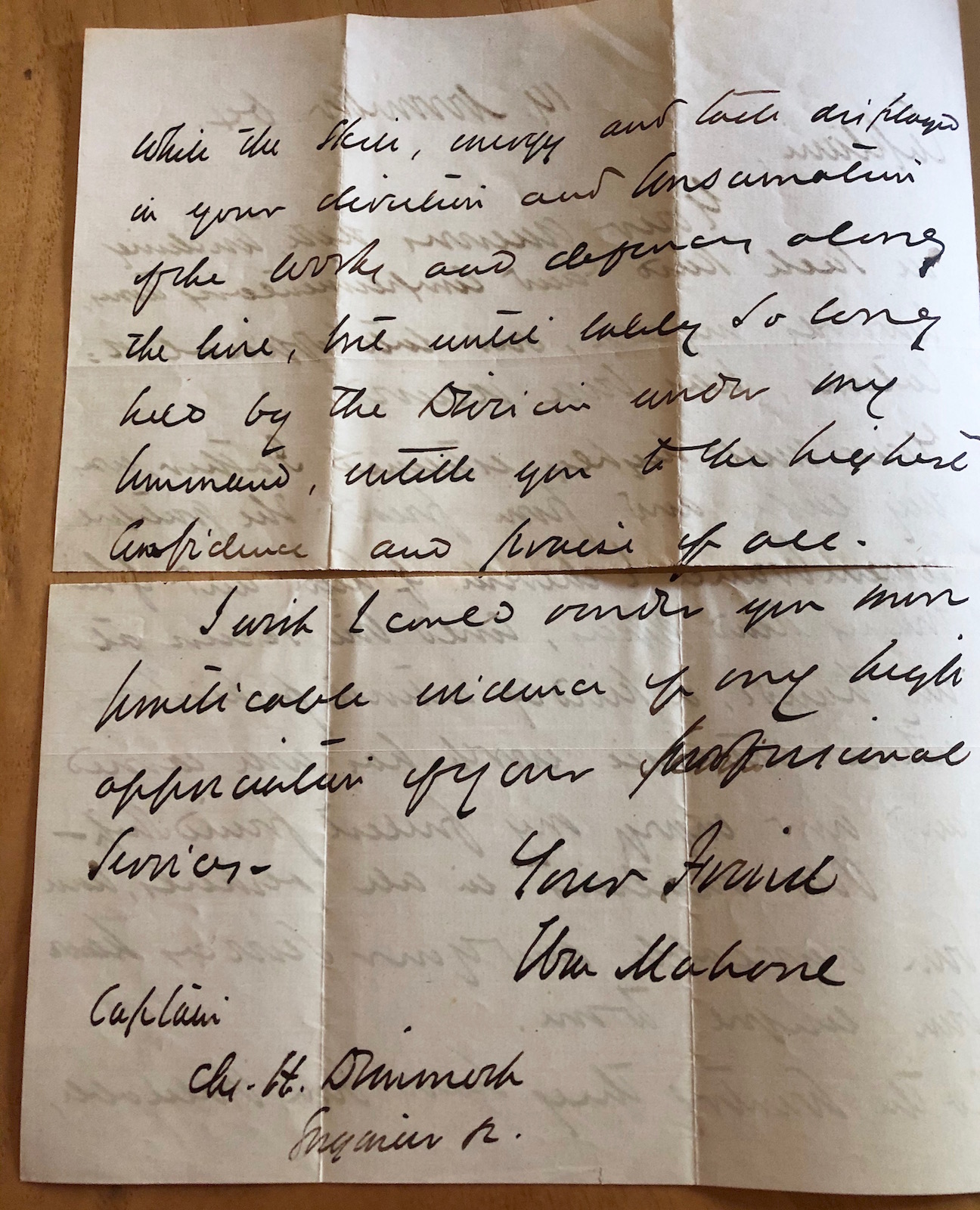

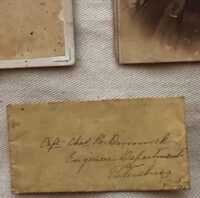

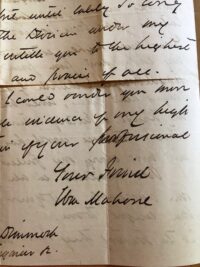

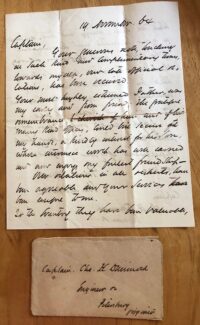

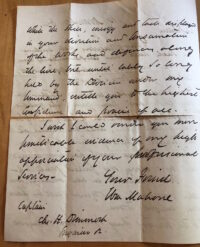

- Hand written letter to Capt. Dimmock, dated Nov. 1864, from Gen. Wm. Mahone; in Mahone’s hand and signed by him; accompanied by the original cover addressed to Captain Dimmock by Gen. Mahone

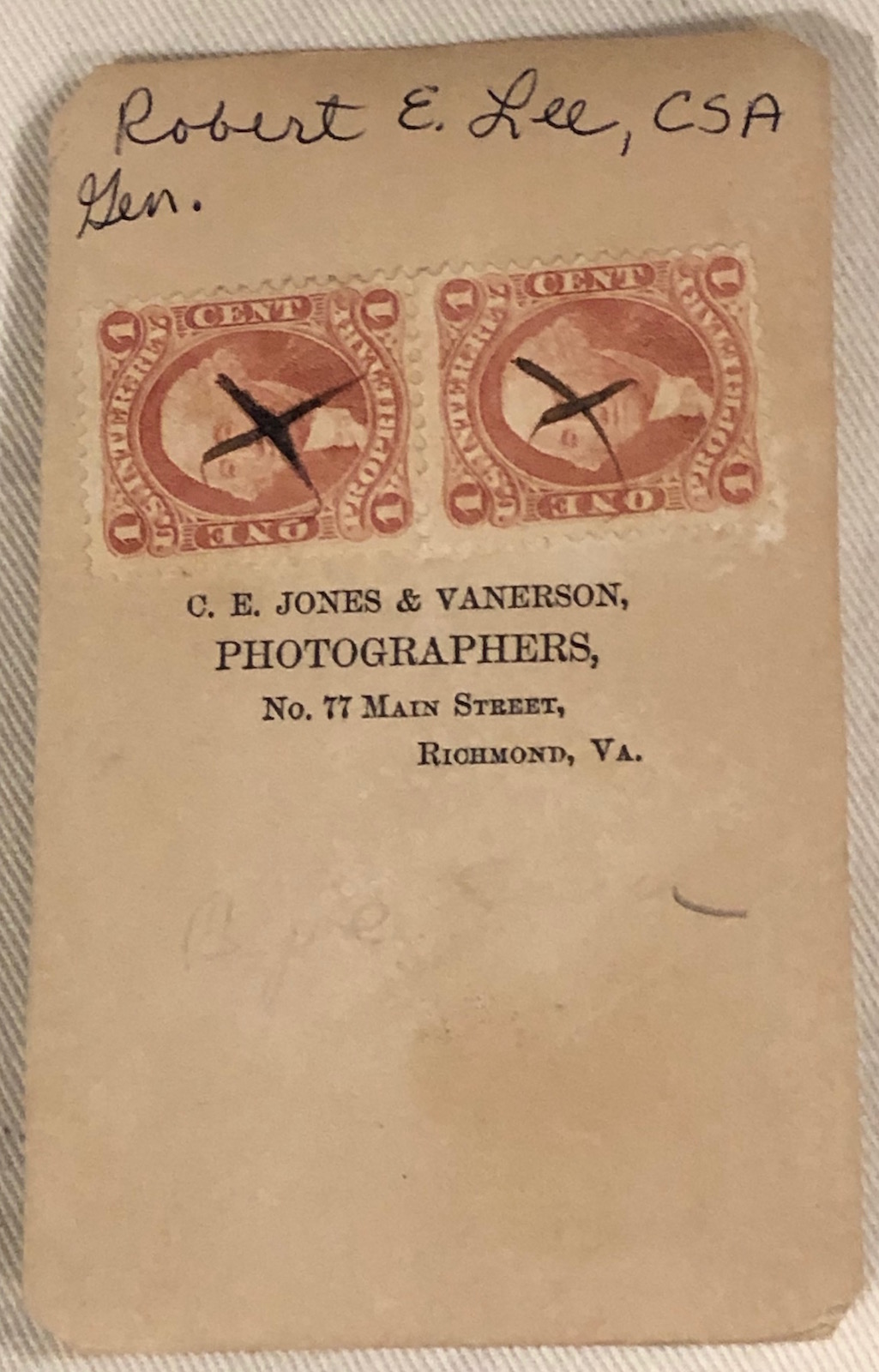

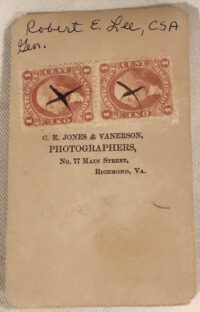

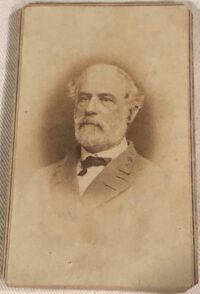

- CDV of Gen. R.E. Lee; from life; war time image with a Vannerson BM

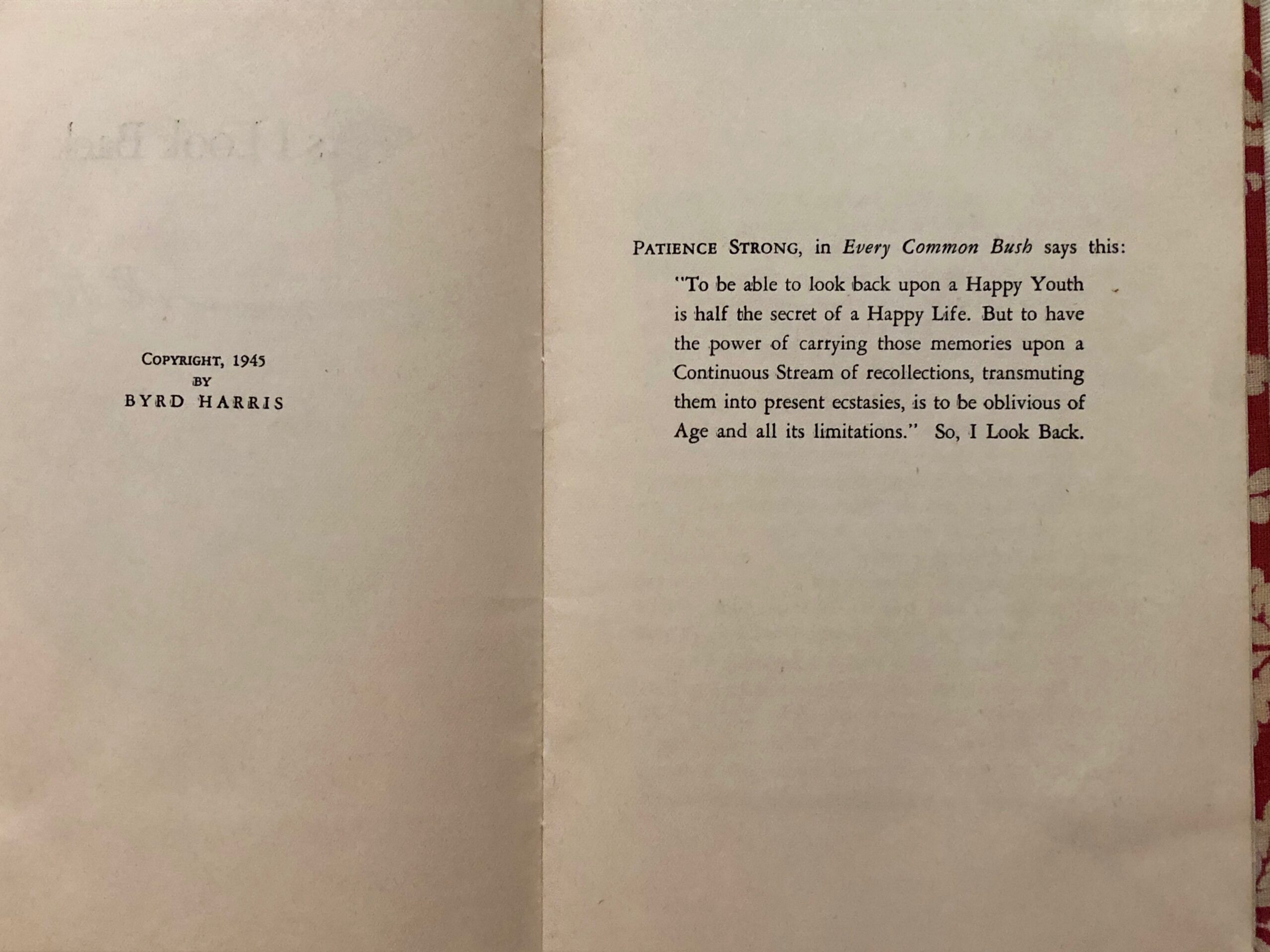

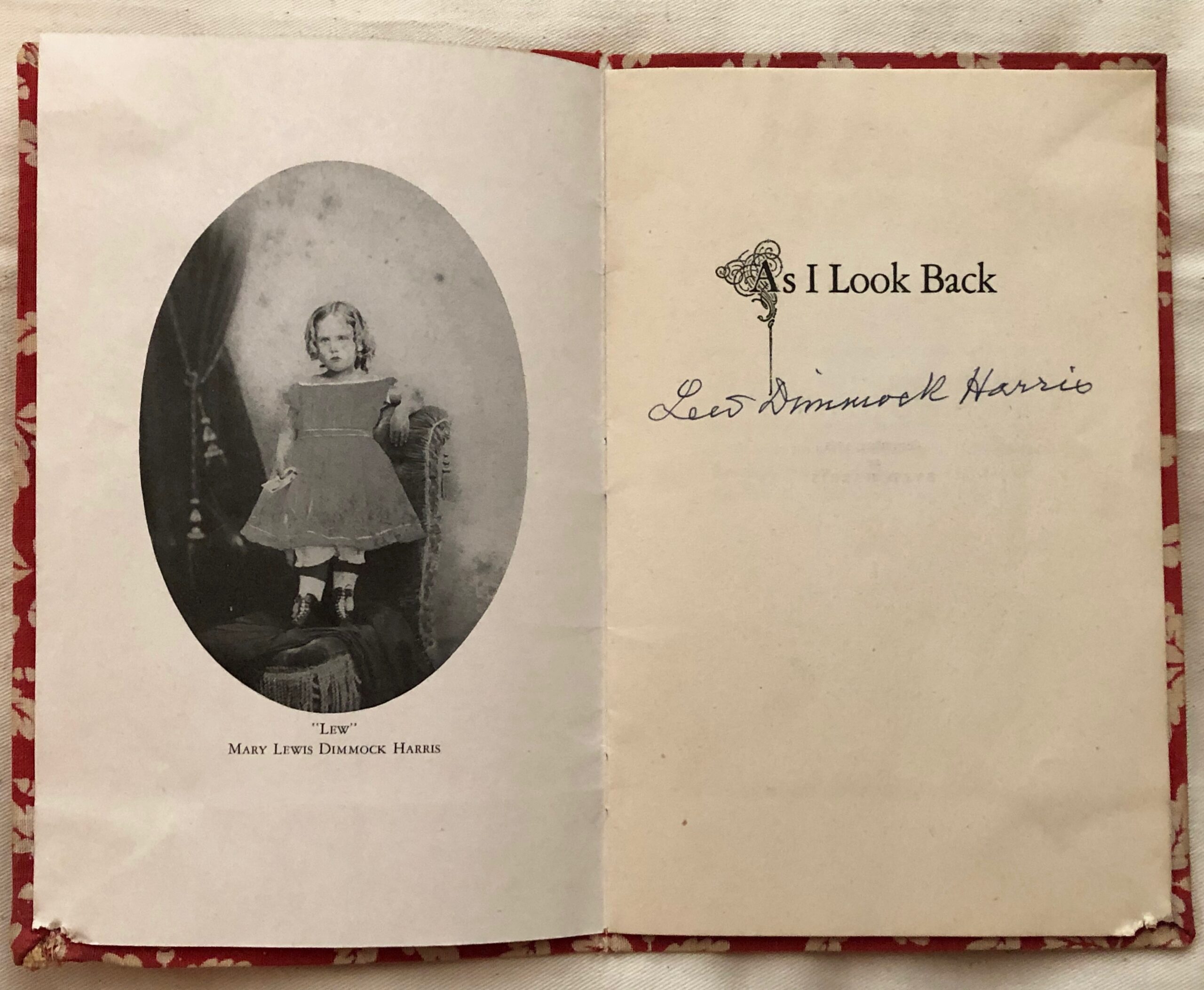

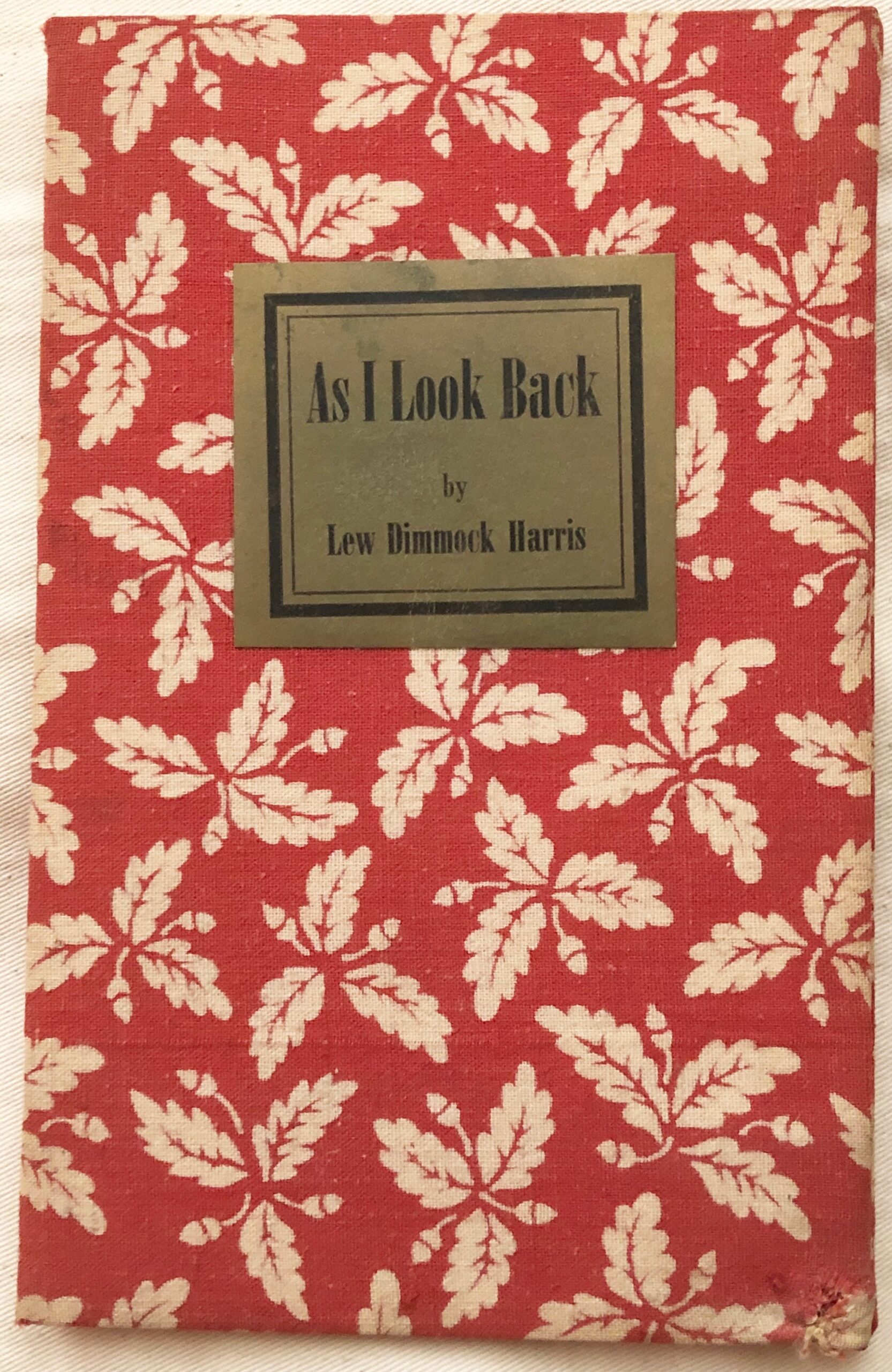

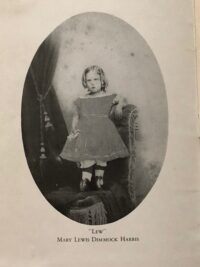

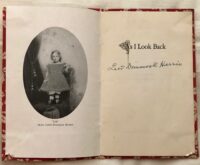

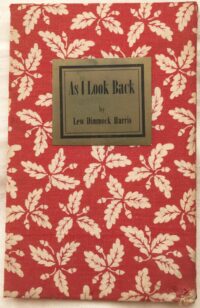

- Book written by Capt. Dimmock’s daughter; published in 1943 – the book eloquently describes the construction of the memorial pyramid in Hollywood Cemetery and Dimmock’s daughter’s childhood memories

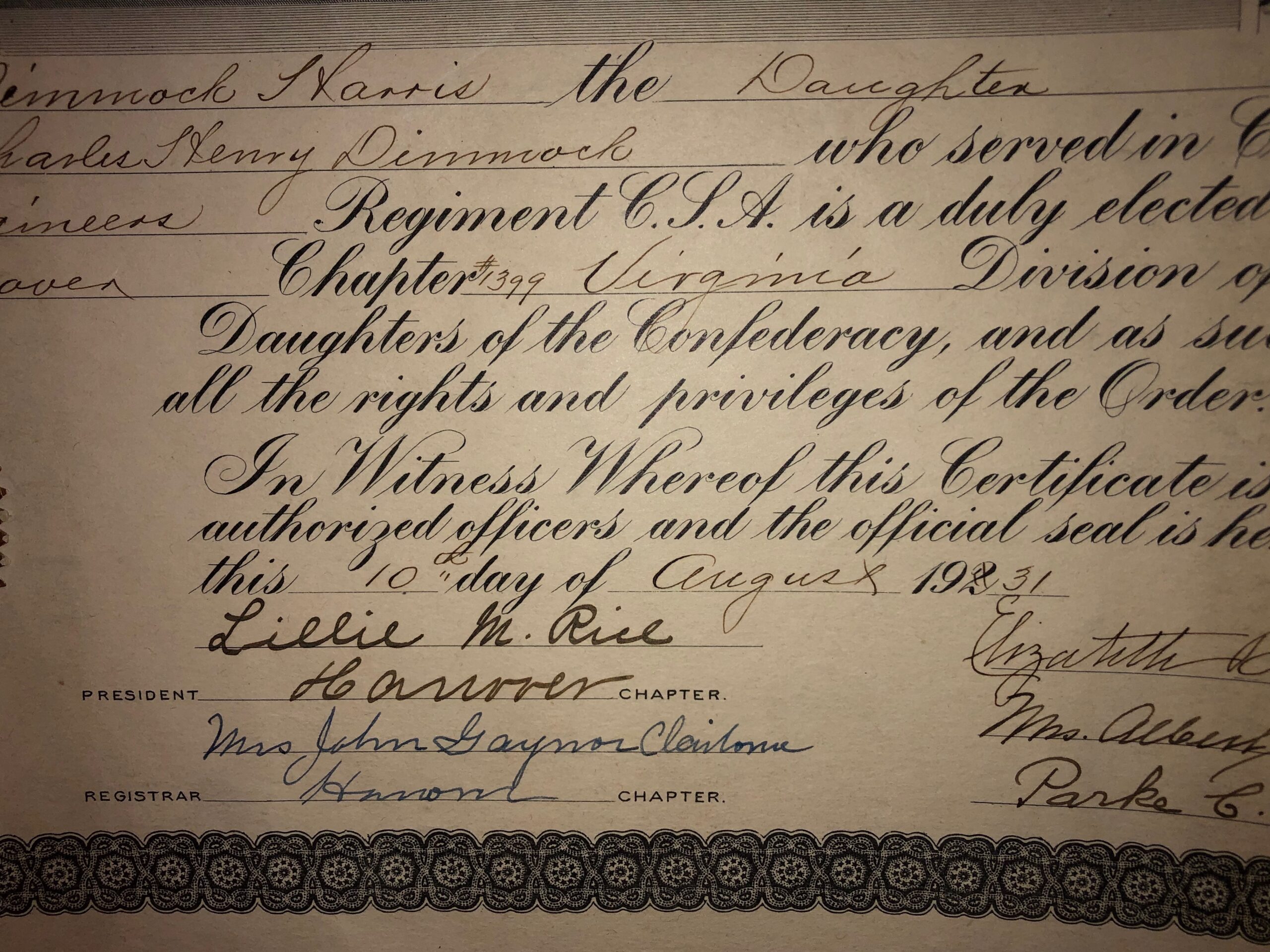

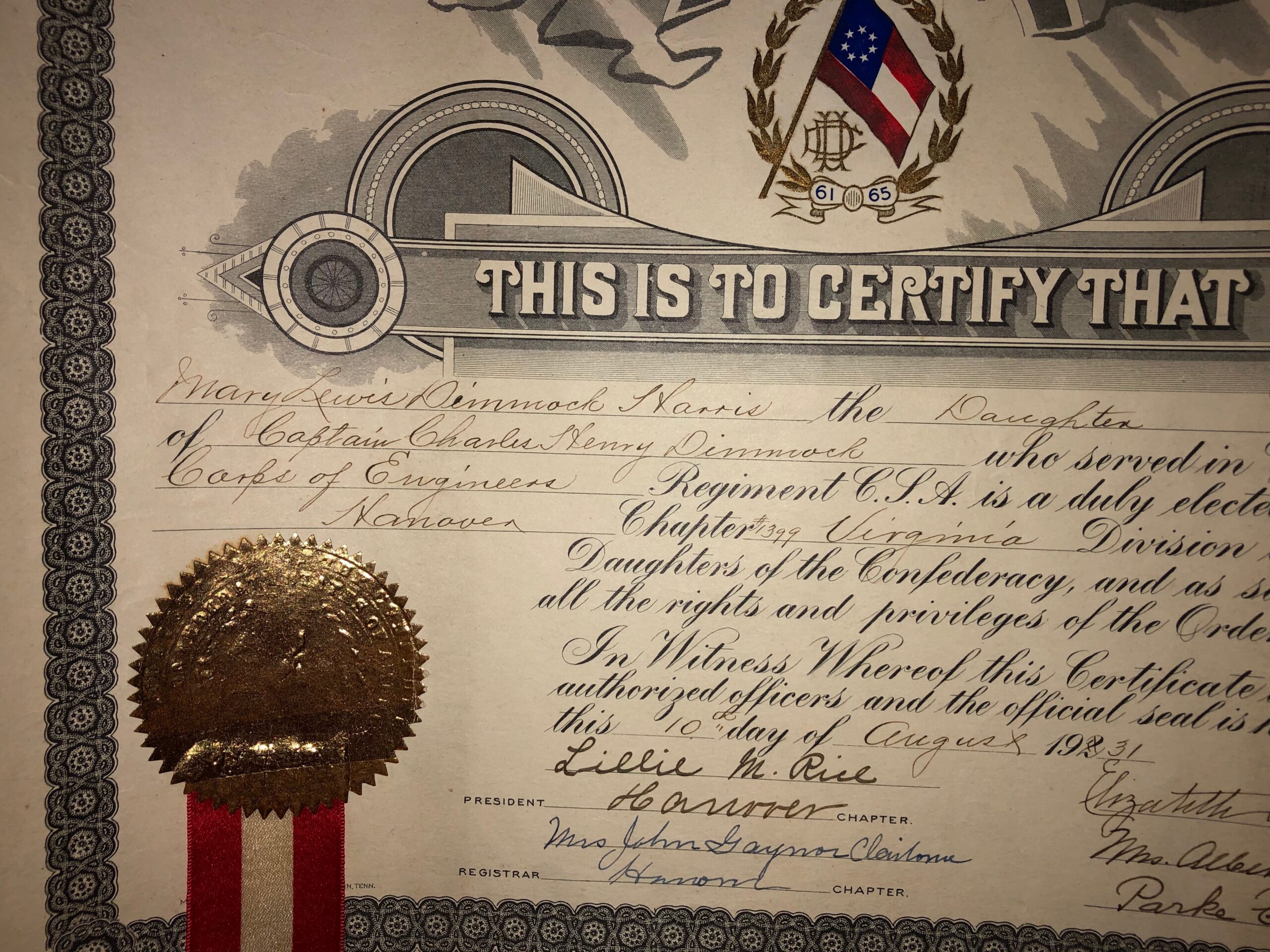

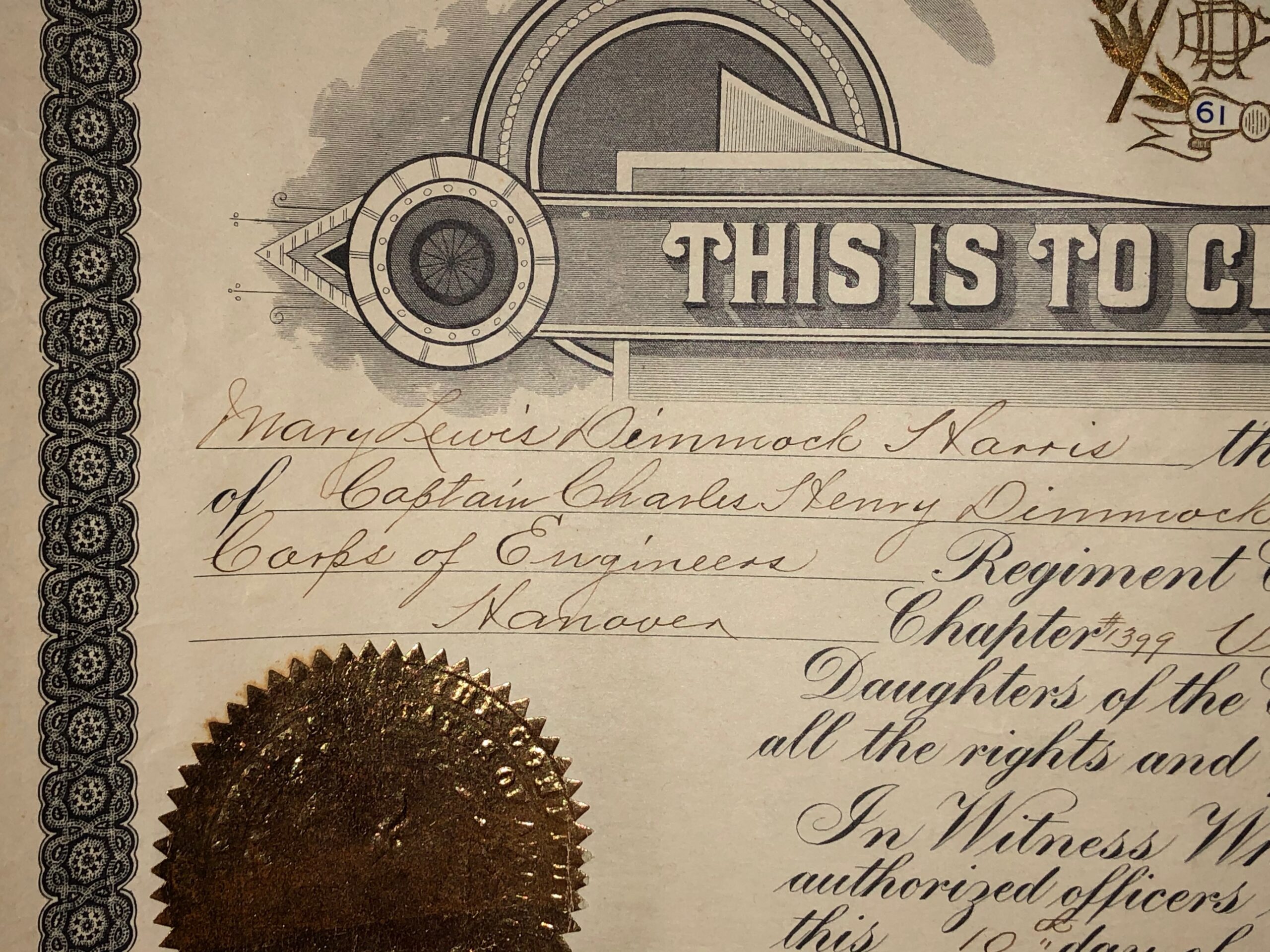

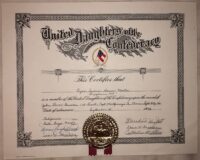

- 3 Dimmock family UDC documents confirming membership – to include a 1930s UDC membership for Dimmock’s daughter

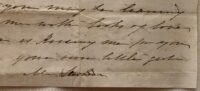

- Copy of Gen. Mahone’s letter written by Capt. Dimmock and sent to his wife during the Siege of Petersburg – in a war time letter to his wife, Dimmock mentions that he is sending a copy of Mahone’s letter to her, written by Capt. Dimmock

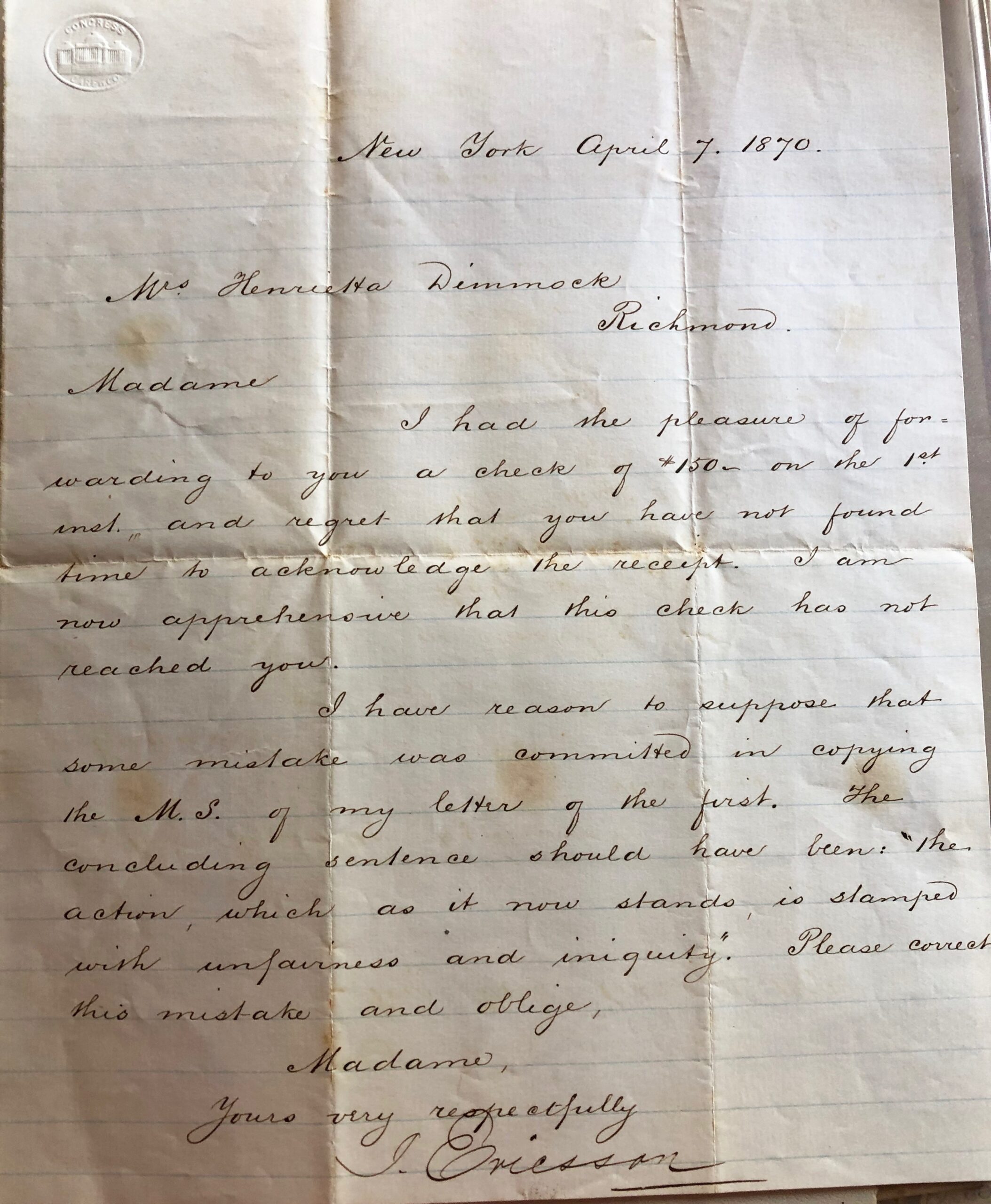

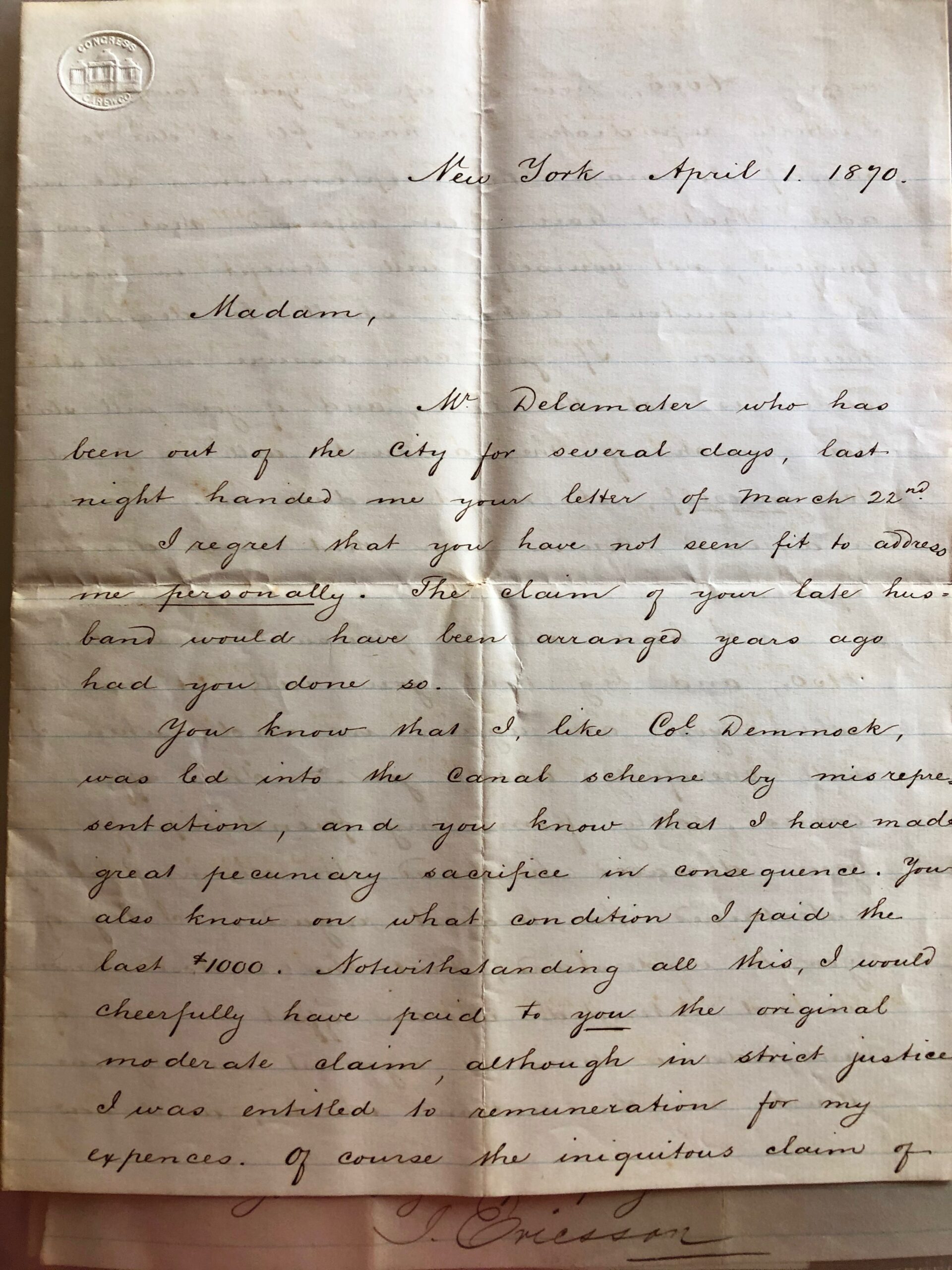

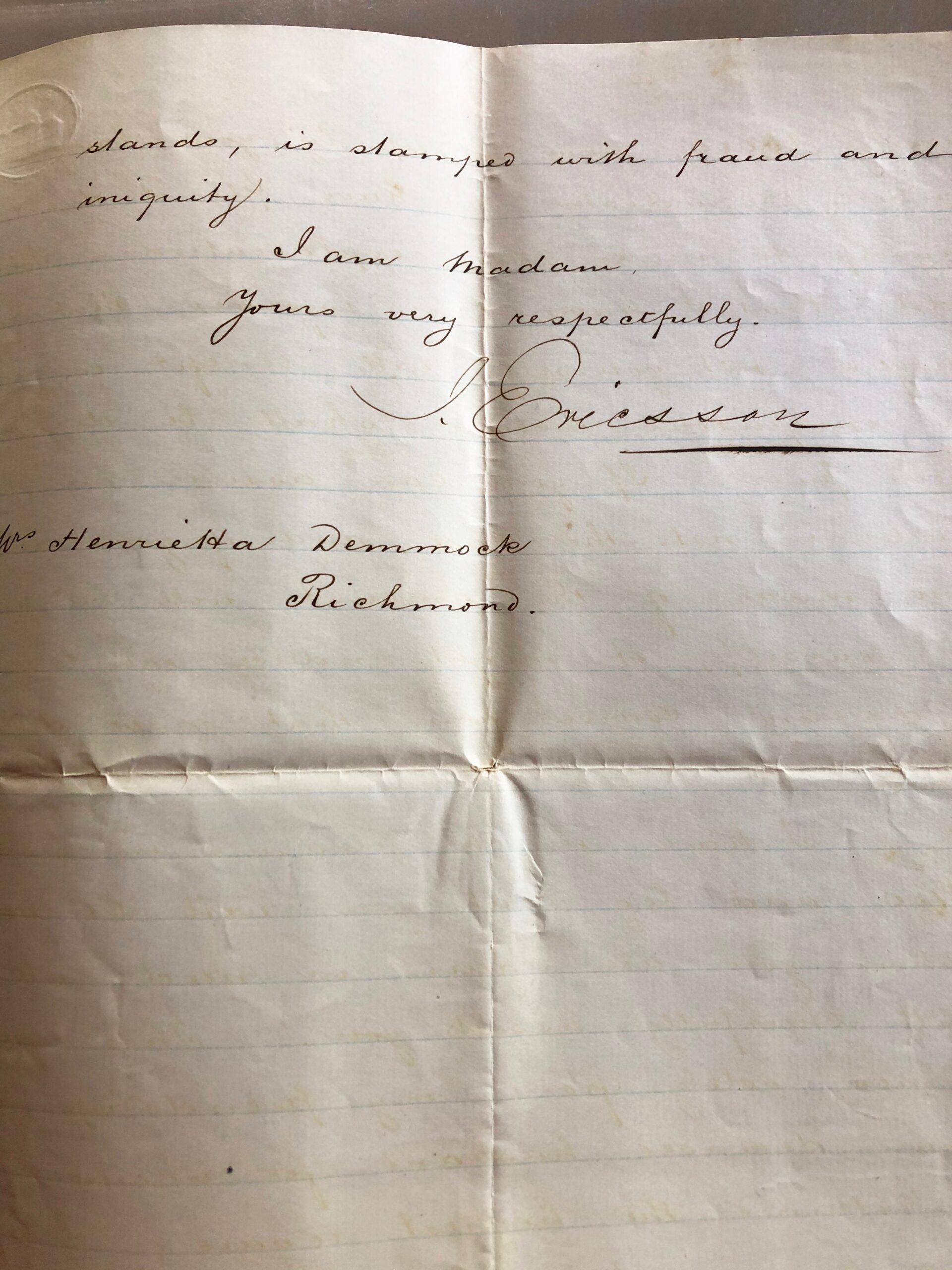

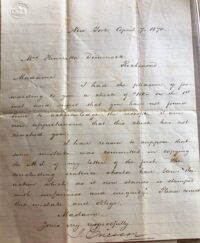

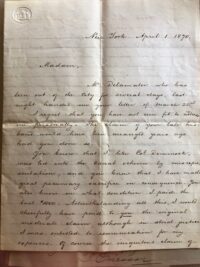

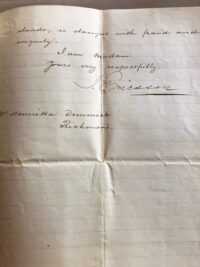

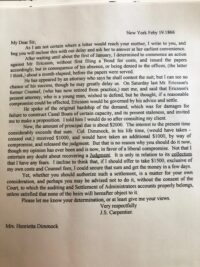

- Two letters written and signed by the USS Monitor’s designer, John Ericsson, regarding business dealings with Capt. Dimmock – Dimmock apparently had contacted Ericsson to design and build several canal boats – Ericsson did not fulfill his part of the bargain resulting in legal issues with the Dimmocks – their attorney’s letter to Ericsson is included

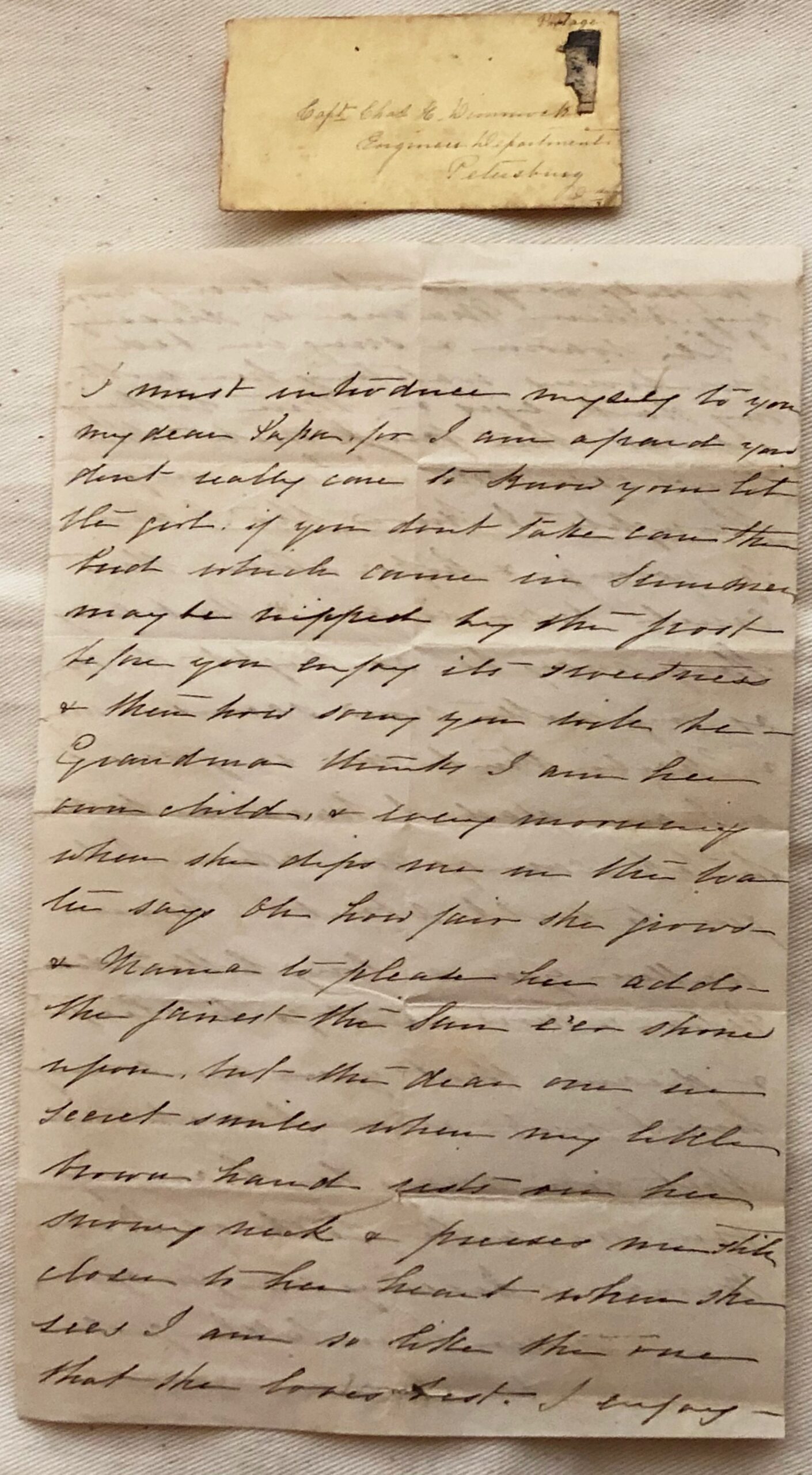

- Letter written by wife of Capt. Dimmock to the Captain, during the Siege of Petersburg, “introducing” his new daughter to her father; with cover addressed to the Captain, in the lines, in Petersburg

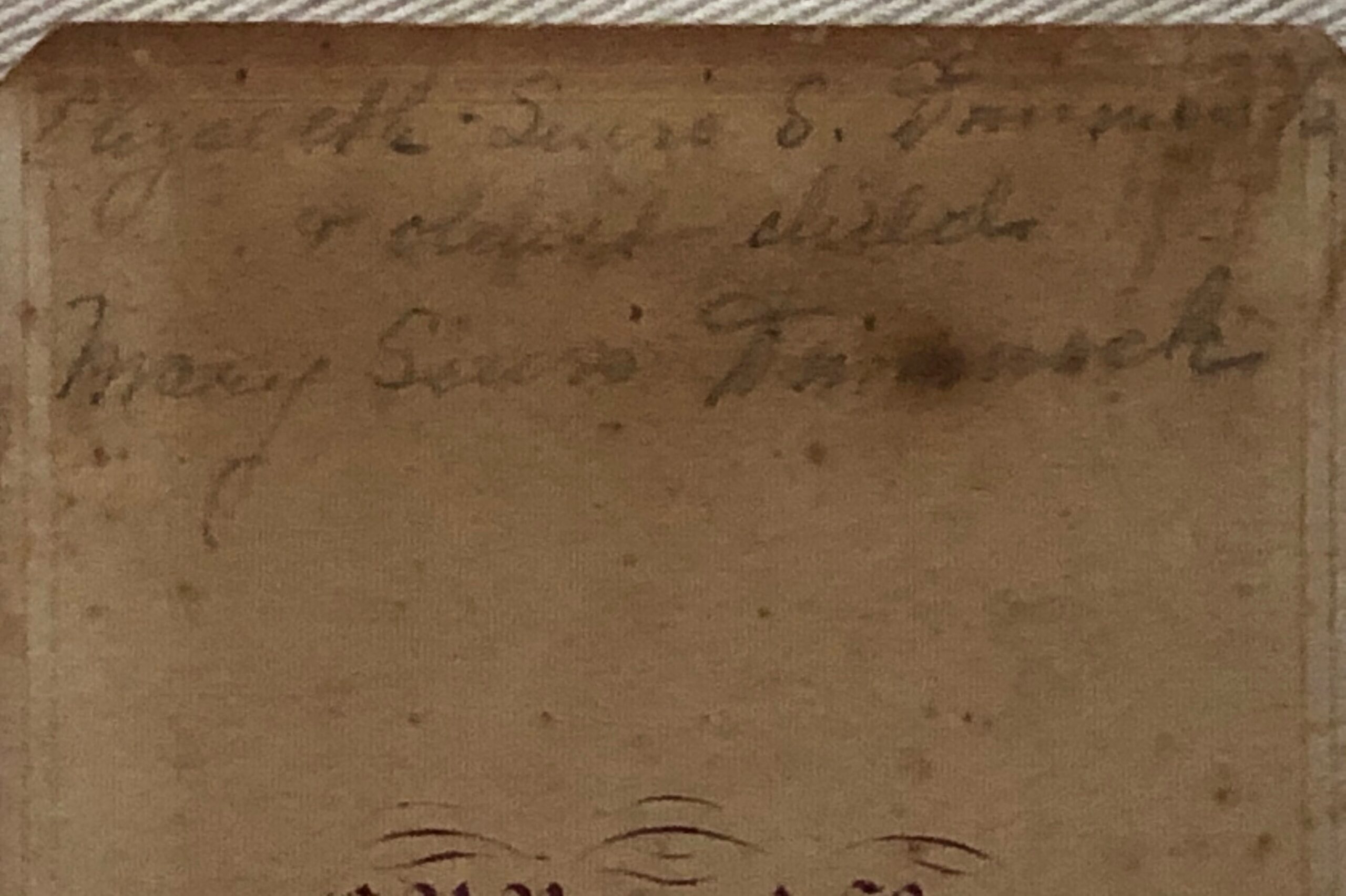

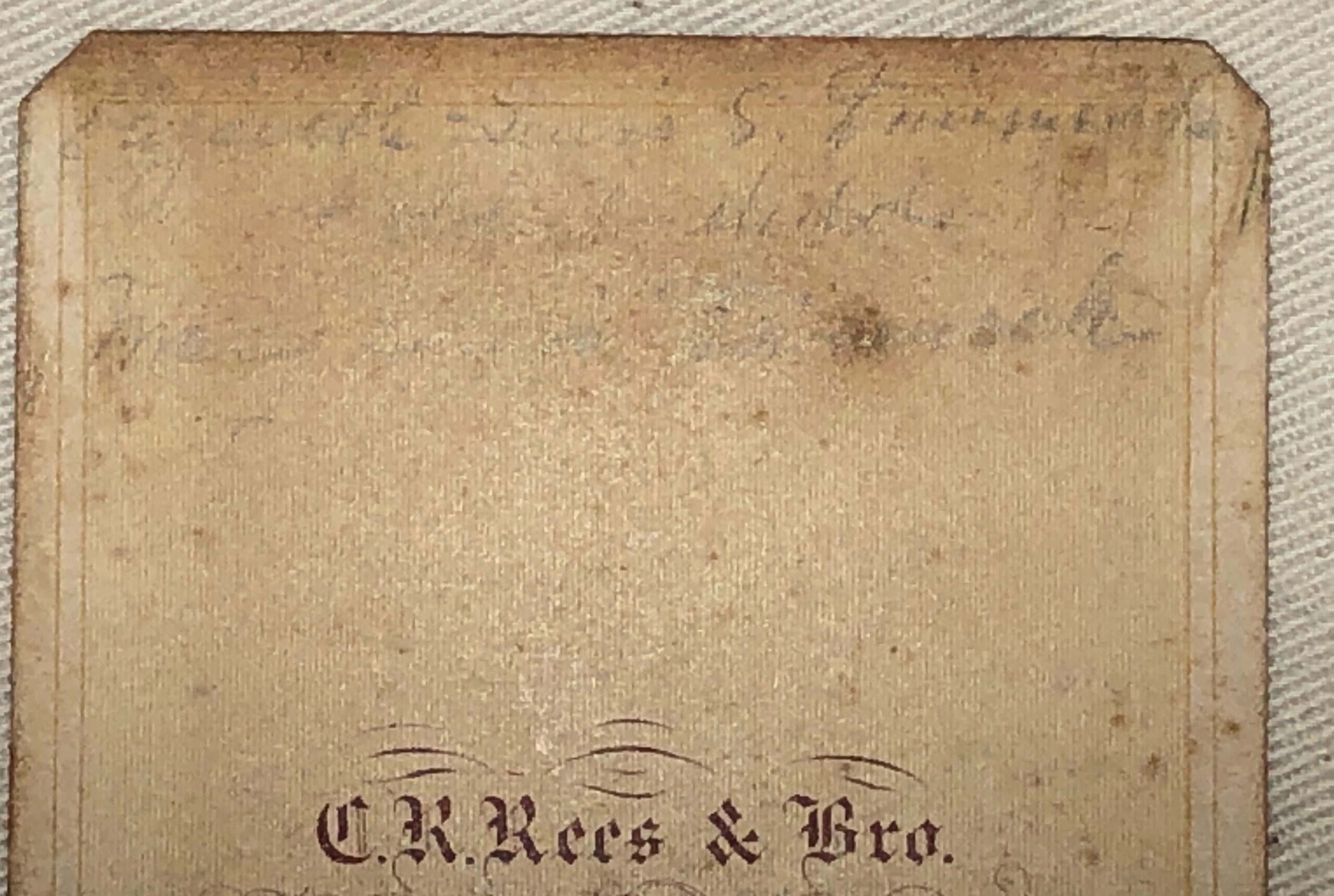

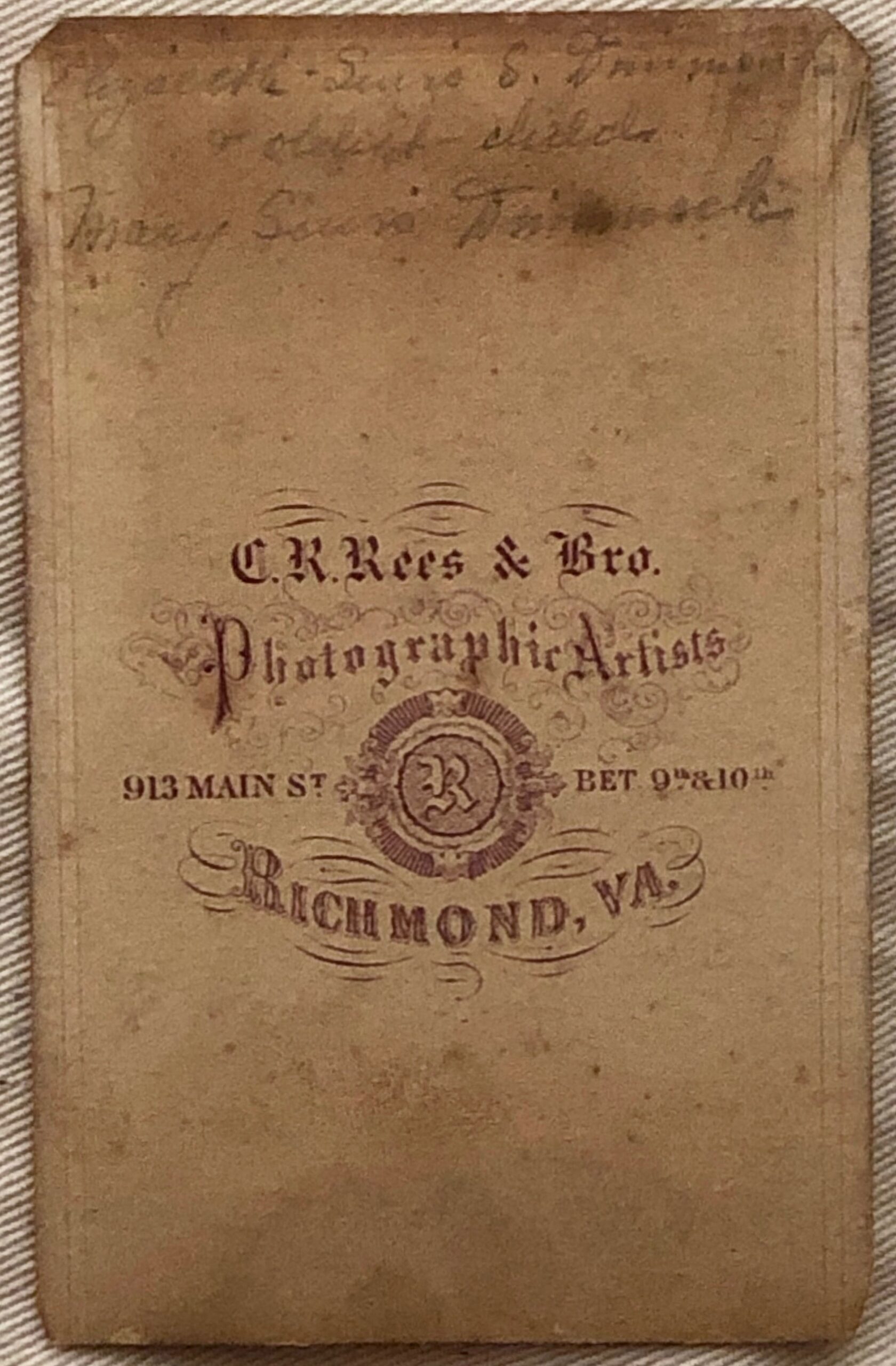

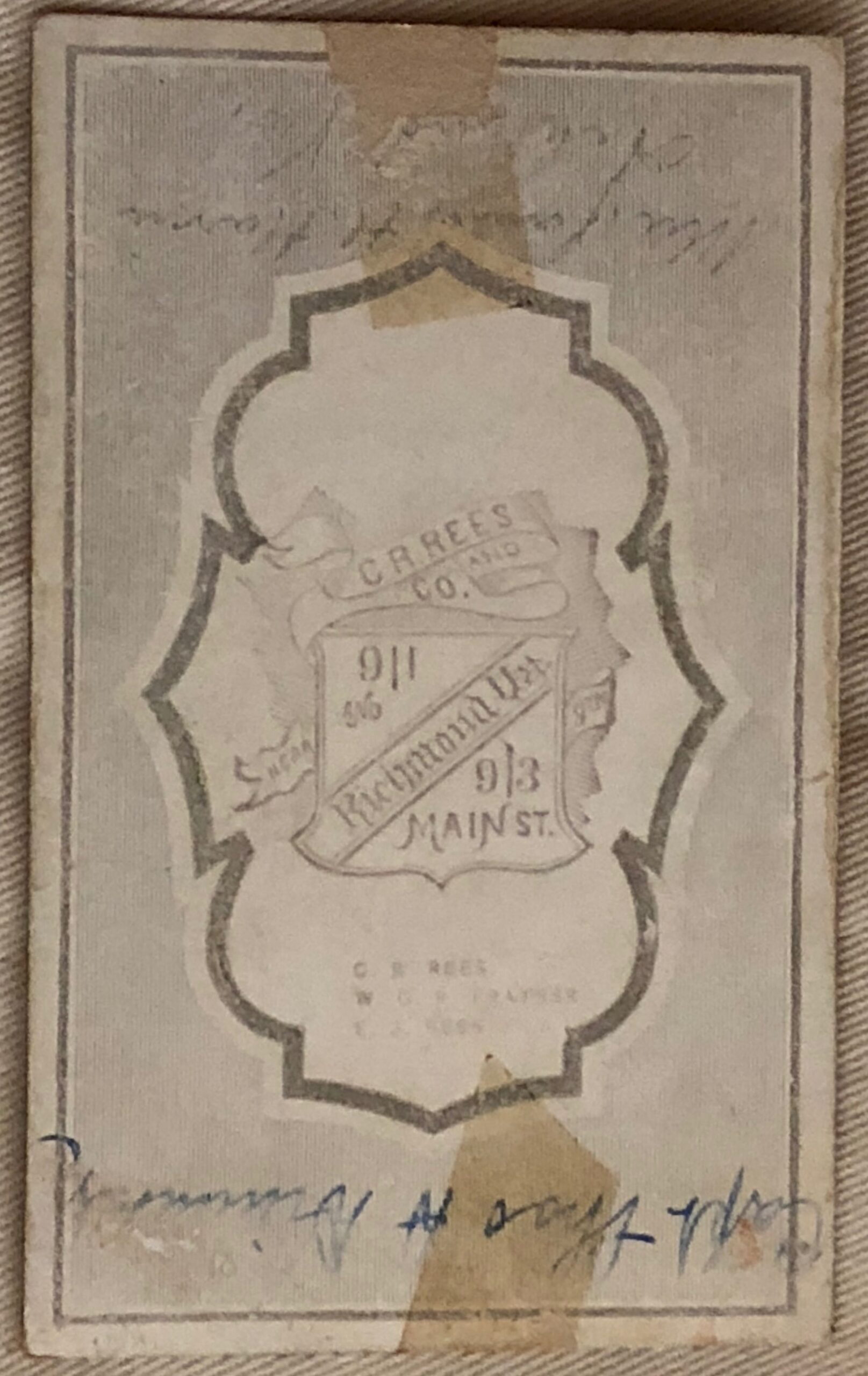

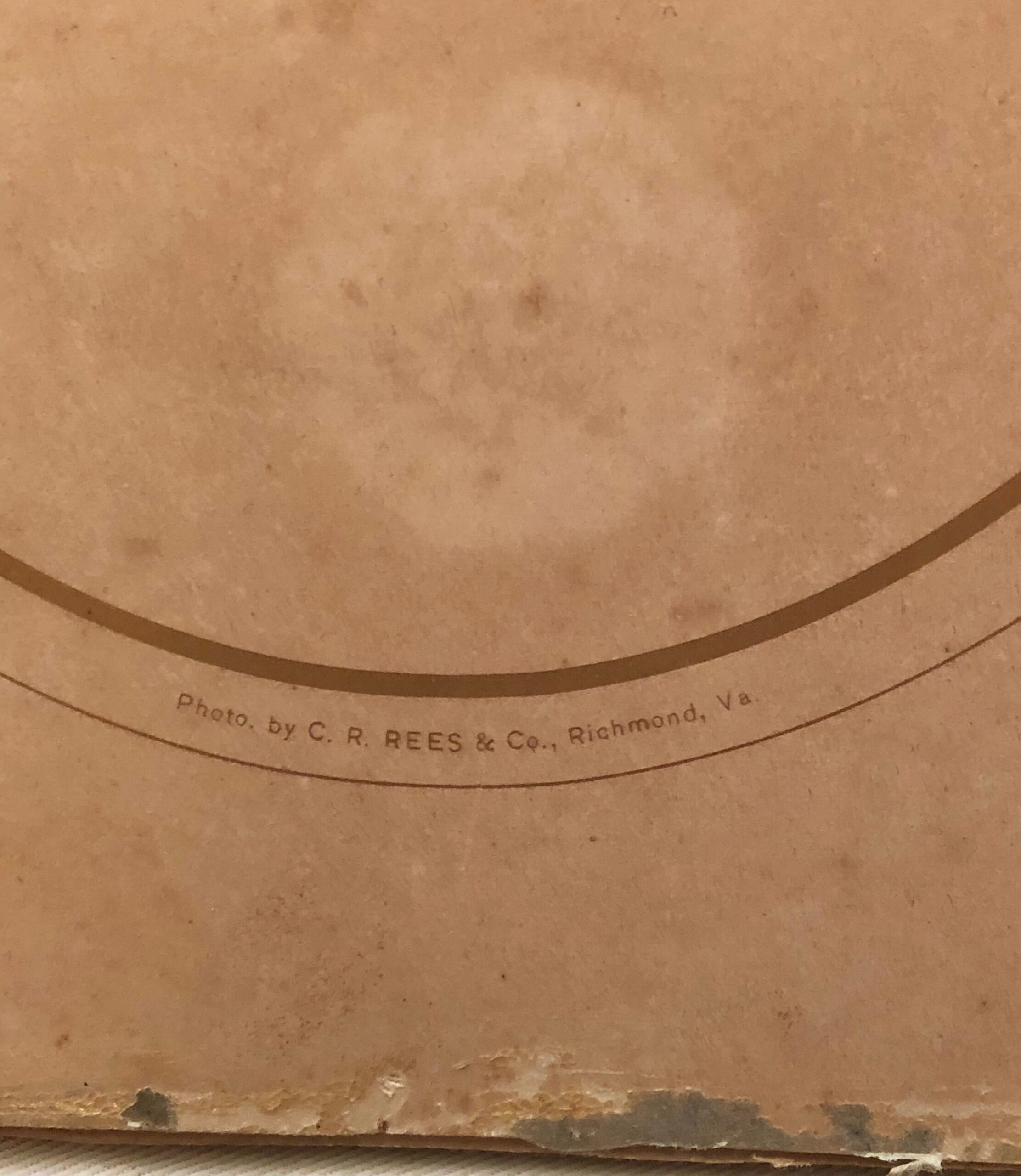

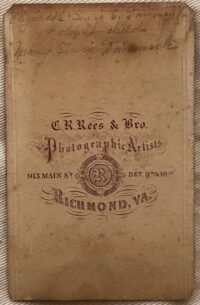

- Large post war albumen of Capt. Dimmock by famed Richmond photographer, C.R. Rees

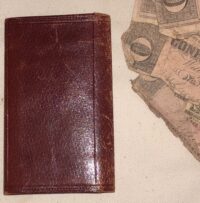

- Dimmock’s billfold, containing five Confederate currency bills

- Pre-CW, 1/6 plate ambrotype of Capt. Dimmock

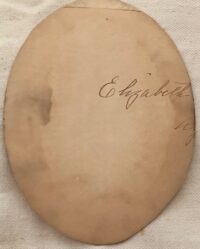

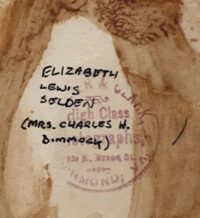

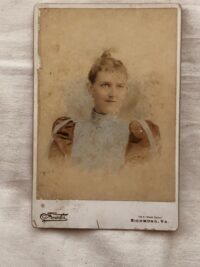

- Cabinet card image of Capt. Dimmock’s daughter

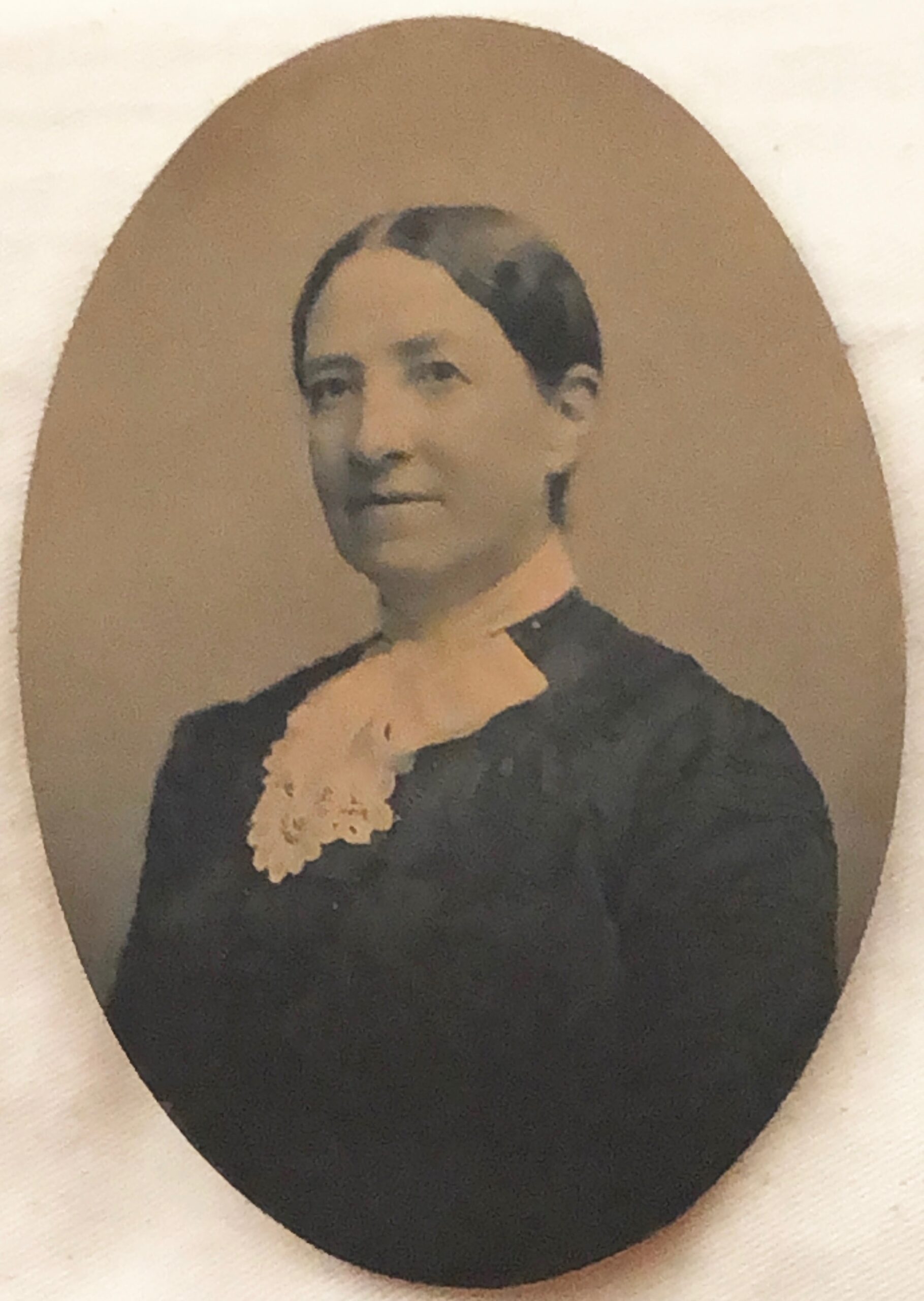

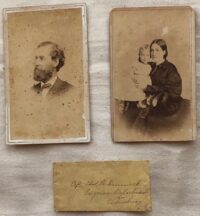

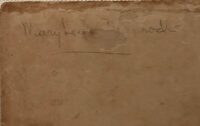

- Two CDVs – postwar images of Capt. Dimmock; postwar image of Mrs. Dimmock and daughter

- CW period, small cover addressed to Capt. Dimmock in Petersburg, during the siege

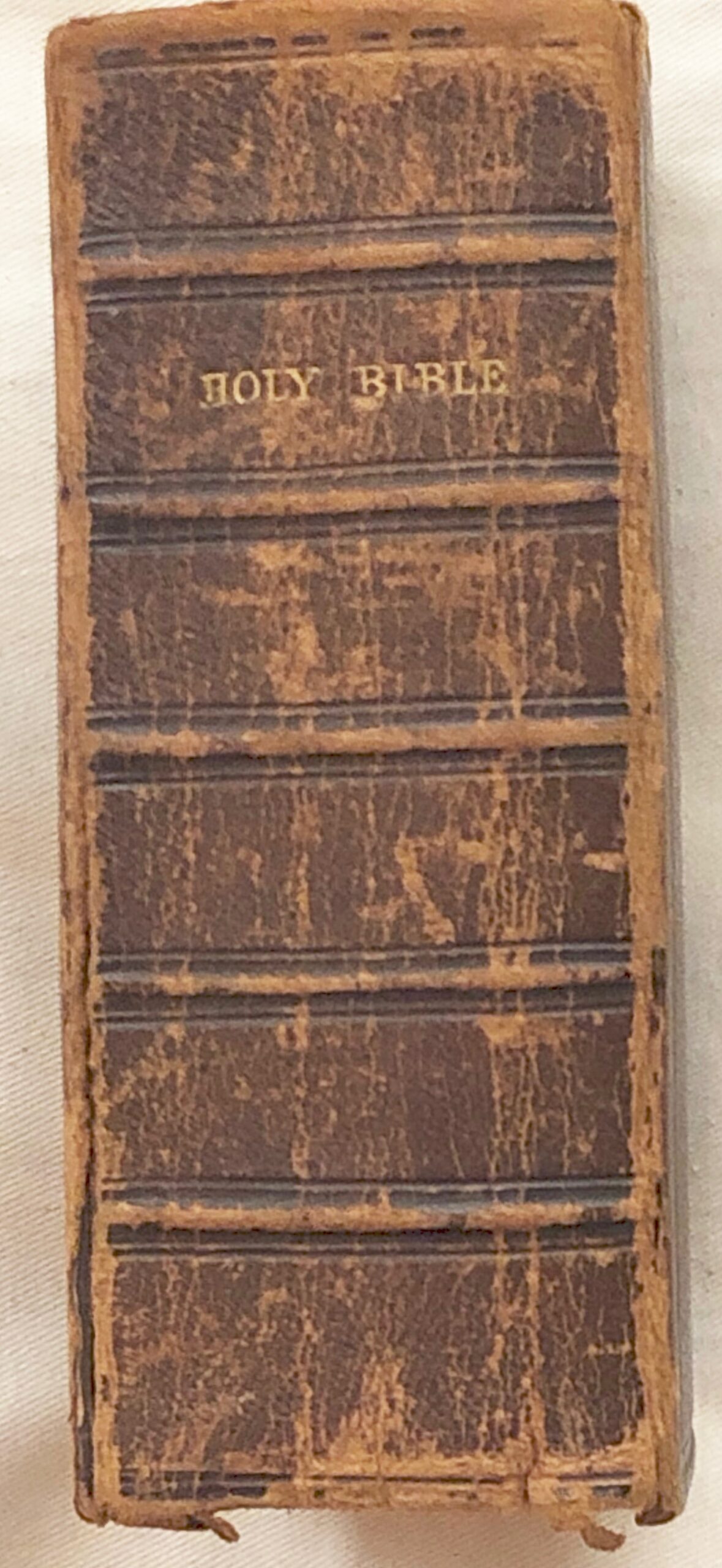

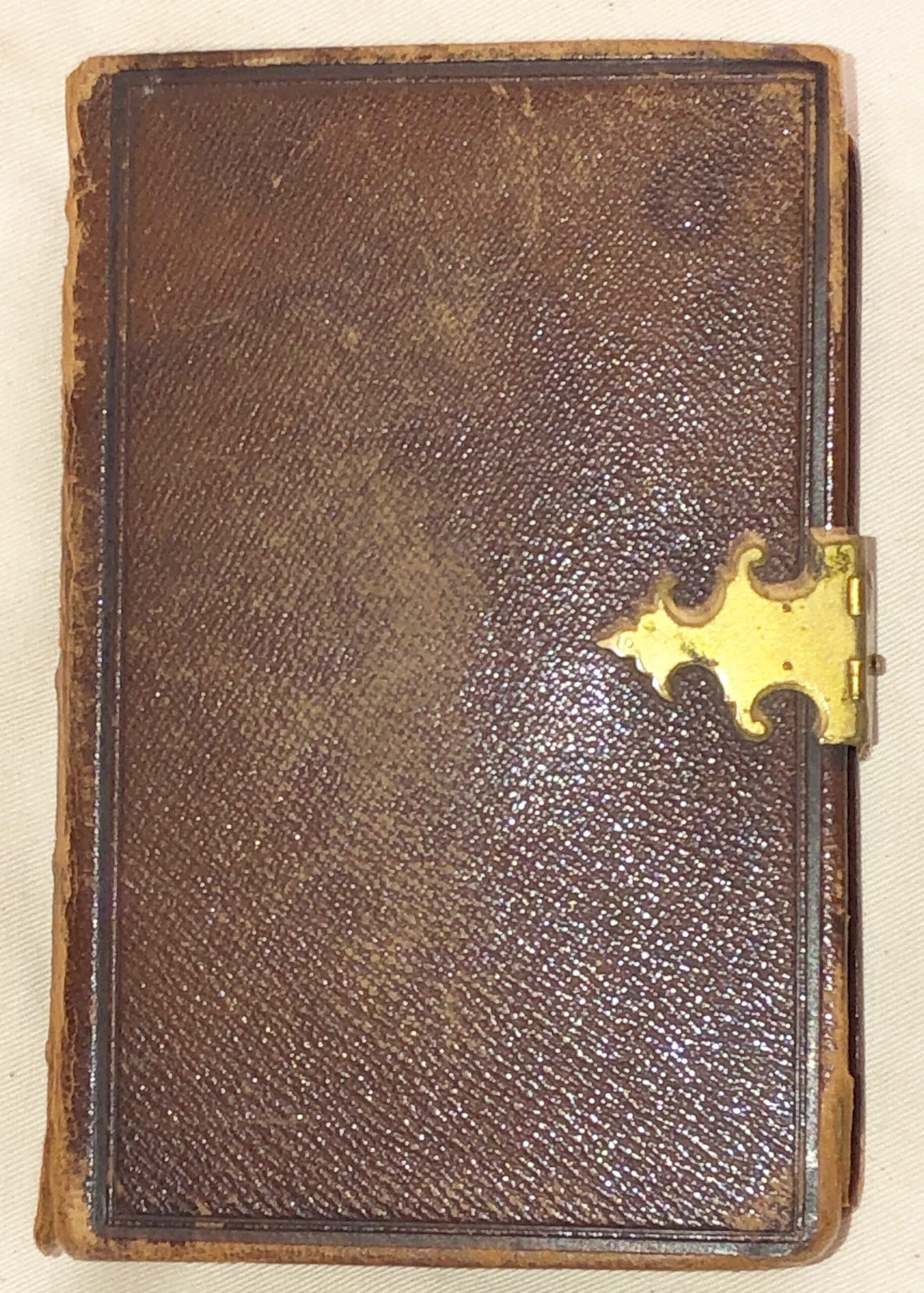

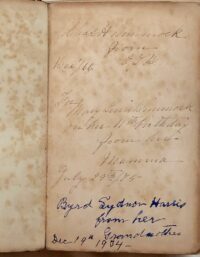

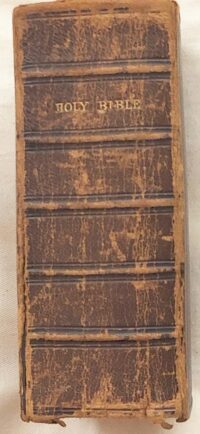

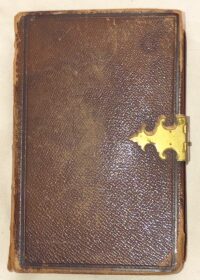

- Postwar Dimmock family Bible, with a presentation to Capt. Dimmock inked on an opening flyleaf

- Numerous pre and postwar documents in Dimmock’s hand – multiple legal documents and deeds

- Framed postwar image of Mrs. Dimmock

Charles Dimmock, an army officer who during the Civil War served as the chief of ordnance for Virginia, and Henrietta Maria Fraser Johnson Dimmock. The family moved to Portsmouth, Virginia, late in the 1830s and then early in the 1840s to Richmond, where Dimmock attended the Richmond Academy. He worked as a civil engineer for several railroads, including the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad Company and the Philadelphia and Baltimore Railroad Company, based in Baltimore. On 12 May 1857 Dimmock married Emily Louisa Moale, of that city. They had one daughter and one son. In 1859 Dimmock traveled to New Mexico Territory as a topographer with the United States Topographical Bureau. He returned to Baltimore shortly before his wife died on 12 December 1859. Earlier he had read law in Baltimore, and by 1860 he had opened a practice there.

Civil War Service

After the Virginia convention voted to secede from the United States in April 1861, Dimmock returned to Richmond. He supervised construction of defenses at Fort Norfolk, at Craney Island near Portsmouth, and at Roanoke Island in Dare County, North Carolina, before he received a commission on 17 May as a captain in the Corps of Engineers of the Provisional Army of Virginia. In mid-October, Dimmock was assigned to Gloucester Point on the York River. Noting his ability, his superiors recommended him early in 1862 for a position in the nascent Confederate Corps of Engineers. Dimmock mustered in at the lower rank of first lieutenant. On 12 February 1862 he protested his demotion in a letter to the Confederate secretary of war and on 18 March won reinstatement as captain.

In May 1862 Dimmock was dispatched to build obstructions in the Appomattox River near Petersburg in response to the Union campaign on the Peninsula. After initial surveys conducted by others in August 1862, Dimmock began the design and then directed the construction of a system of defenses—ten miles of fortifications and fifty-five batteries around the city of Petersburg—that would later be known as the Dimmock Line. He required a large labor force, and slaves made up for the shortage of white Confederate manpower. Having completed the project by the middle of 1863, Dimmock had begun supervising the construction of a new bridge across the Appomattox River by July. In Richmond on 14 October 1863 he married Elizabeth Lewis Selden. They had four daughters and one son.

In honor of Dimmock’s dedication to the defense of their city, Petersburg residents presented him with a stallion and riding equipment in January 1864. Later that year the Dimmock Line held against a Union attack on 9 June. Dimmock was reassigned in December to the Army of Northern Virginia, with which he served until the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865. Dimmock took the amnesty oath on 25 May and returned to Richmond, where he resumed his civilian life as an architect and civil engineer. He tried his hand at literary pursuits and published a twenty-four-page poem, The Modern: A Fragment (1866), in which he condemned the vapid nature of modern society.

Monument to the Confederate Dead

With the cessation of hostilities, Richmonders quickly mobilized a campaign for Confederate memorialization. A bazaar held by the Hollywood Memorial Association of the Ladies of Richmond in April 1867 raised $18,000 for the purpose of erecting a monument in Hollywood Cemetery for all Confederate soldiers. Dimmock submitted a design to the selection committee in June. He envisioned a ninety-foot-tall pyramid, made of local stone, held together without mortar, and perhaps covered in creeping ivy. The Hollywood Memorial Association selected his design and laid the cornerstone on 3 December 1868. To great fanfare spectators watched a convict climb ninety feet to the top to place the capstone on 8 November 1869. The pyramid became an enduring symbol of the Lost Cause and a tourist destination at the historic cemetery into the twenty-first century.

Civil Engineer

By 1870 Dimmock had established an architectural firm on Main Street with his younger brother, Marion Johnson Dimmock. On 27 April 1870 the overloaded courtroom floor at the Capitol collapsed, killing about sixty people. Dimmock served on the three-member committee that the General Assembly named to assess the damage and recommend a course of action. In its report presented on 17 May, the committee proposed repairing the Capitol rather than constructing a new building. The assembly granted funds the next month for the suggested repairs and construction.

As part of a slate of Conservative candidates, Dimmock won election as city engineer of Richmond on 26 May 1870. His duties included maintaining and paving streets and sidewalks, maintaining sewers, building bridges, planting trees, and supervising school construction. In March 1871 a group of local builders brought charges of incompetence and price-gouging against Dimmock, but the city council quickly exonerated him and the following year reelected him to the post of engineer. Early in 1872 the Hollywood Memorial Association sent Dimmock to Gettysburg to monitor the ongoing exhumation of Confederate dead from the battlefield. His report to the organization that April expressed his shock at the desecration of the graves by local farmers and recommended that the removal of remains to Hollywood continue.

By that time Dimmock’s health had begun to deteriorate from stomach cancer. In January 1873 he traveled to New York City for an operation. His illness worsened, however, and during the night of 2829 March 1873 Charles Henry Dimmock died at his father-in-law’s home in Gloucester County. He was buried at Hollywood Cemetery, in Richmond. As a testament to his civic service, Richmond’s mayor closed government offices at noon. More than a century after his death a parkway in Colonial Heights, near Petersburg, was named for Dimmock.

Sources Consulted:

Charles H. Dimmock Papers (including birth date in MS biography and death date of 29 Mar. 1873 on copy of 1865 parole), Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Va.; correspondence, lines of verse, drawings, commonplace book, and diary (1859) in Charles H. Dimmock Papers, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Va.; Baltimore Sun, 16 May 1857; Marriage Register, Richmond City (1863), Bureau of Vital Statistics, Record Group 36, Library of Virginia; Richmond Daily Dispatch, 30 Mar. 1871; Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers (1861–1865), War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (1880–1901); Mary H. Mitchell, Hollywood Cemetery: The History of a Southern Shrine (1999), portrait tipped in between 34 and 35; A. Wilson Greene, Civil War Petersburg: Confederate City in the Crucible of War (2006); Gloucester Co. Death Register (died on 29 Mar. 1873); obituaries in Richmond Daily Dispatch, Richmond Enquirer (with variant birth date of 31 Oct. 1831), and Richmond Daily Whig, all 1 Apr. 1873 (died “Friday last,” 28 Mar. 1873), and in Baltimore Sun, 2 Apr. 1873 (died “on Friday”).

The Dimmock Line

The Dimmock Line was a series of fifty-five artillery batteries and connected infantry earthworks that were constructed between 1862 and 1864 in a ten-mile arc around Petersburg during the American Civil War (1861–1865). The earthen fortifications were built using Confederate soldiers and enslaved laborers and covered lands east, south, and west of Petersburg. They were constructed to protect the city’s industry and railroads in the event that Petersburg was attacked. Union troops finally attacked Petersburg directly and elements of the Dimmock Line fell to them in mid-June 1864, which began the Petersburg Campaign.

The Dimmock Line

“The order of work on the general defenses … should be to occupy the favorable points in the circuit around the place (far enough from the town to prevent the enemy coming within bombarding distance) by suitable detached works, closed toward the town, with stockades. The intermediate spaces to be filled up afterward by rifle-pits or lines of infantry cover. The works to be earthworks, with such obstructions in advance as you may find the means and time to construct, such as abatis, pits, felled timber, & c.”

— Chief Engineer Jeremy F. Gilmer

| Capt. Charles H. Dimmock

In May 1862, as McClellan’s Army of the Potomac advanced on Richmond up the Peninsula north of James River, prominent citizens of Petersburg petitioned the Confederate Secretary of War George Randolph to provide for the defense of their city. But little happened until the Federal army had actually retreated and dug in around Harrison’s Landing, some twenty miles downstream. Still, there remained the threat of cavalry raids on the Southside or even of a thrust against vulnerable Petersburg, if McClellan had been so inclined. In early July, Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill took command of the Department of North Carolina, which, at the time, included Southside Virginia and made his headquarters in Petersburg. Almost immediately, Hill dispatched a brigade of his infantry to the Nathaniel Friend farm (White Hill) east of the city to work on a line of entrenchments to cover the fork of the Prince George County and Jordan Point roads. This early work likely consisted of epaulements for artillery and a simple rifle trench for infantry. When it became clear that McClellan and his army were being withdrawn from the enclave at Harrison’s Landing, the Confederate high command at last focused on possible threats south of James River. Two former Regular Army engineers, Col. Jeremy F. Gilmer and Lt. Col. Walter H. Stevens were dispatched to bring their engineering prowess to bear on the defenses at Petersburg. Gilmer, a West Point graduate (Class of 1839), resigned the service in June 1861 and signed on as Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston’s chief engineer. After recovering from a wound received at Shiloh, Gilmer was appointed chief engineer of the Department of Northern Virginia and chief of Richmond’s Engineering Bureau, a position he would hold until the end of the war. Walter Stevens, a West Point graduate (Class of 1848) and Regular Army engineer, resigned the service in March 1861 when his adopted state of Texas seceded. Stevens was named to the engineers in the Confederate army, where he labored on the defenses of Richmond. Gilmer and Stevens were considered two of the most capable military engineers of the Confederacy. In early August, Gilmer and Stevens (possibly accompanied by a young civil engineer named Charles Dimmock, Jr.) rode out along the high ground outside of Petersburg and traced a ten-mile long semicircle of fifty-five artillery strong points with both flanks anchored on the Appomattox River. Gilmer’s philosophy of fortifying had changed little when he offered advice on constructing Atlanta’s defenses a year later: “The order of work on the general defenses … should be to occupy the favorable points in the circuit around the place (far enough from the town to prevent the enemy coming within bombarding distance) by suitable detached works, closed toward the town, with stockades. The intermediate spaces to be filled up afterward by rifle-pits or lines of infantry cover. The works to be earthworks, with such obstructions in advance as you may find the means and time to construct, such as abatis, pits, felled timber, & c.” (Gilmer to Grant, O.R. vol. 30, pt. 4:489). Within a week of the engineers’ tour, General Hill had assigned three infantry brigades and impressed nearly 1,200 slaves and free blacks to work on the line. This first intense phase of work focused on the lines east of town, from the Appomattox to Jerusalem Plank Road, where Gilmer and Stevens had lavished most of their attention. With construction underway, the senior engineers bowed out and relinquished oversight to Capt. Dimmock. His constant presence and attention throughout 1862 and 1863 ensured that his name would be attached to Petersburg’s fortifications — the Dimmock Line. |

The Dimmock Line (shown in red) extended in a semi-circle around the city of Petersburg with both flanks anchored on the Appomattox River. It consisted of fifty-five numbered batteries of various configurations and armament. Detail from Confederate “Map of the Approaches to Petersburg and their Defenses,” Gilmer, 1863. [Official Atlas, plate 40:1]

Early Stevens map (1862) of Surveys and Reconnoissances in Vicinity of Petersburg. [University of North Carolina] This appears to show (dashed line) the proposed general location of the Dimmock Line. See detail below.

the Gregory House (unnamed) on the Jerusalem Plank Road. |

Charles Henry Dimmock was born in Baltimore, on October 18, 1831. His family afterwards settled in Richmond, where his father became the city surveyor. Dimmock studied mathematics and engineering under Claude Crozet, who was Principal Engineer and Surveyor for the Virginia Board of Public Works and a founder of the Virginia Military Institute. Under Crozet’s direction, Dimmock worked as engineer on various civil projects in Virginia — primarily roads and railroads. With the start of the Civil War, Dimmock was commissioned captain of engineers in the Confederate States Army. Undoubtedly, his career was aided by the fact that his father, Col. Charles Dimmock Sr., was by this time Chief of Ordnance for the state of Virginia and Inspector of Richmond’s fortifications.

Despite a lack of military experience, one of Dimmock’s early war assignments was to oversee construction of fortifications on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. These works were not considered successful. He then returned to Virginia to oversee work on the Yorktown fortifications with others. As McClellan’s army moved up the Peninsula toward Richmond, Capt. Dimmock was sent to Petersburg to obstruct the Appomattox River to stymie the approach of Union gunboats. Dimmock then worked on a new military railroad bridge over the Appomattox.

With the departure of Gilmer and Stevens, Capt. Dimmock inherited the formidable task of fortifying the city. Military affairs in North Carolina in November and December drew off most of the soldiers and slave owners demanded the return of their property, leaving him starved for labor. Dimmock solved the problem by establishing a skilled cadre of 200 free black and slave workers who worked from 8 am until 4 pm daily for regular wages. After that, the work proceeded slowly but steadily.

Anticipating attack from the direction of City Point, much labor was lavished on the eastern front from the Appomattox River past the Jerusalem Plank Road. Beyond that the works were more or less sketched in — artillery batteries were started, connecting infantry lines were left until manpower was available.

Monument to Confederate War Dead – Stone Pyramid in Hollywood Cemetery

LOCATION: Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond’s Oregon Hill neighborhood.

ARTIST: Design originated from engineer Charles Henry Dimmock.

DEDICATION: November 8, 1869. (Cornerstone was laid Dec. 3, 1868)

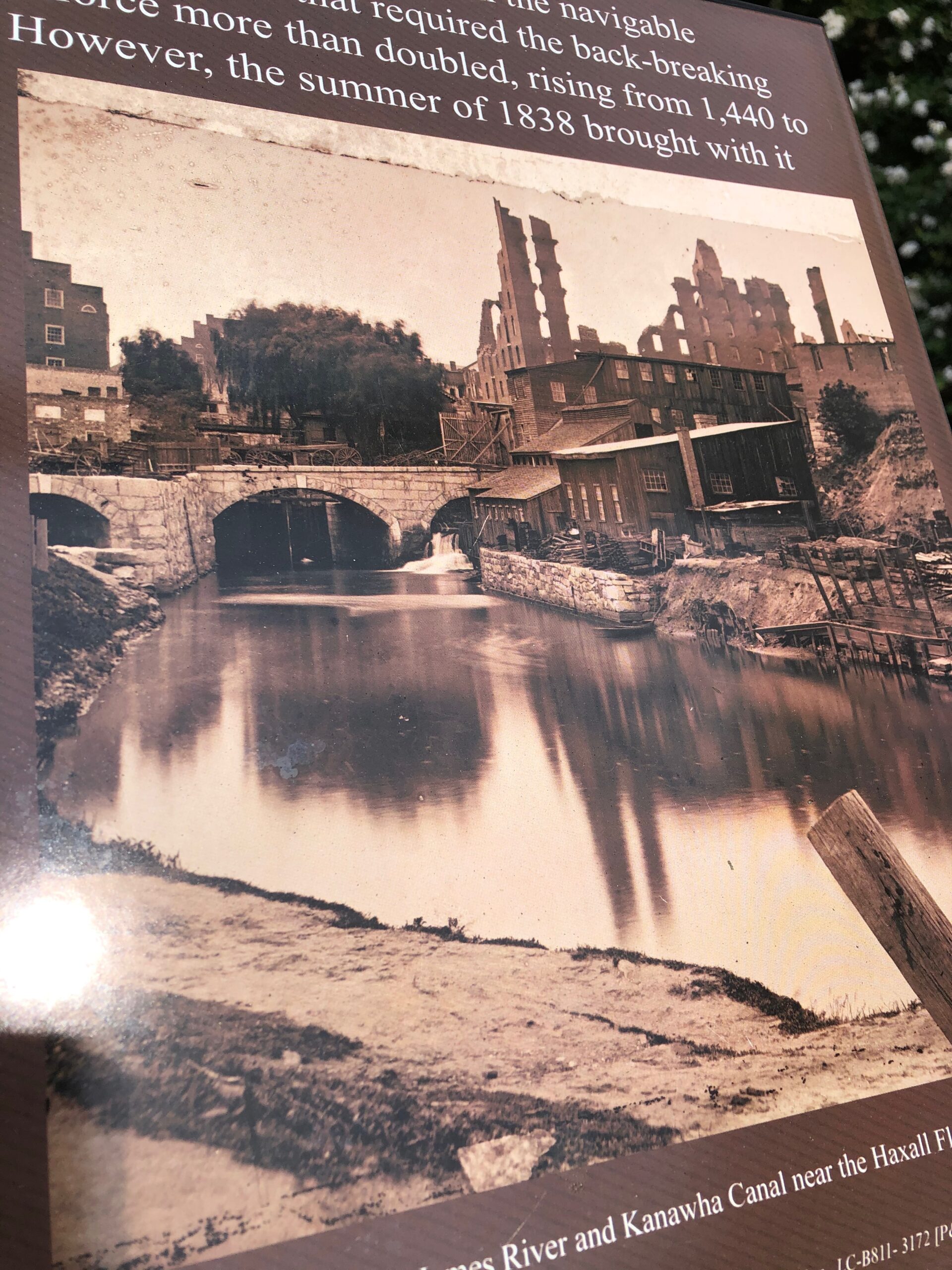

DESCRIPTION: The famed 90-foot pyramid is made with large blocks of James River granite. The blocks were stacked without bonding. Built overlooking the cemetery’s Soldiers’ Section. It is a monument to the 18,000 Confederate enlisted men buried in the cemetery.

* * *

The pyramid took a year to build and there were many accidents during construction. Thomas Stanley, a Lynchburg convict working with the construction crew, made the perilous climb to the top to lower the capstone into place.

The plaque reads: “A memorial to the Confederate women of Virginia, 1861-1865. The legislature of Virginia of 1914, has at the solicitation of Ladies Hollywood Memorial Association and United Daughters of Confederacy of Virginia placed in perpetual care this section where lie buried eighteen thousand confederate soldiers.

A chapter (Oct. 1996) in Harry Kollatz Jr.’s book, True Richmond Stories, retold the tale of the capstone’s placement, and how prisoner Thomas Stanley — assumed to have come from the nearby state penitentiary on Gamble’s Hill — volunteered to perform the dangerous honor:

And thus it was that a horse thief came to be on the work gang for Dimmock’s pyramid. The knots in the hoisting ropes were tied too close to the top and the stone wouldn’t go past them. Stanley poured water on the ropes, causing them to shrink the needed inches. Then, as a breathless crowd watched, the prisoner put himself between the mass of hanging rock and the pyramid and righted the stone to its seat.

Everyone that has heard of this legend assumes that Stanley went free after this accomplishment. Kollatz’s story cleared that up, somewhat:

In the release box of his prison schedule, the simple penciled notation reads “transferred.” There is no mention of when or where. A romantic notion suggests itself: the warden opened a gate and told Stanley to go and never come back…

Seeing this monument is an essential to anyone that visits Richmond. The first time I saw the pyramid, I was shocked by its size and towering presence in the scenic cemetery. It can be seen from many points near Oregon Hill. It is easy to imagine the stones being brought in from either the Kanawha Canal — located just below Hollywood — or Belle Isle — just a bit further below the canal and across the James River.

***Please contact us for specific questions regarding any needed additional information regarding the grouping and contents.