ShopJune 19, 2025

-

Id’d Chasseur Style Civil War NCO’s Kepi Cap – Sgt. Billings Hodgdon Co. B 5th Maine Infantry

$3,450Id’d Chasseur Style Civil War NCO’s Kepi Cap – Sgt. Billings Hodgdon Co. B 5th Maine InfantryJune 19, 2025 -

Civil War Period Dress Epaulettes of Col. Henry Larcom Abbot(t) of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery

$1,750Civil War Period Dress Epaulettes of Col. Henry Larcom Abbot(t) of the 1st Connecticut Heavy ArtilleryJune 16, 2025 -

Civil War Period Cockades – Virginia Mourning Cockade and a Patriotic Cockade

Civil War Period Cockades – Virginia Mourning Cockade and a Patriotic CockadeJune 9, 2025 -

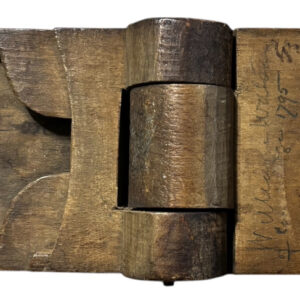

Unusual Handmade Folding Wood Traveling Bootjack Dated 1795

$325Unusual Handmade Folding Wood Traveling Bootjack Dated 1795June 6, 2025 -

1/6 Plate Tintype of Three Union Cavalrymen – Two Wearing Corps Badges

$4751/6 Plate Tintype of Three Union Cavalrymen – Two Wearing Corps BadgesJune 5, 2025 -

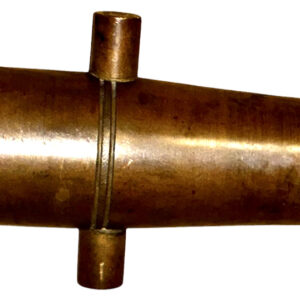

Mid-19th Century Civil War Period Cast Brass Diminutive Cannon Tube (Model)

$275Mid-19th Century Civil War Period Cast Brass Diminutive Cannon Tube (Model)June 5, 2025 -

Significant Group of Civil War Officer’s Shoulder Boards, Hat Badges and Various Officer and Enlisted Man’s Insignia

Significant Group of Civil War Officer’s Shoulder Boards, Hat Badges and Various Officer and Enlisted Man’s InsigniaJune 1, 2025 -

Pre-Civil War Period Id’d Beaver Stovepipe Hat in its Original Box – Id’d to Brig. General George Williamson Balloch

$850Pre-Civil War Period Id’d Beaver Stovepipe Hat in its Original Box – Id’d to Brig. General George Williamson BallochMay 31, 2025 -

Id’d Civil War Camp Trunk – Jason Morse, Adjutant of the 111th USCT

$1,750Id’d Civil War Camp Trunk – Jason Morse, Adjutant of the 111th USCTMay 30, 2025 -

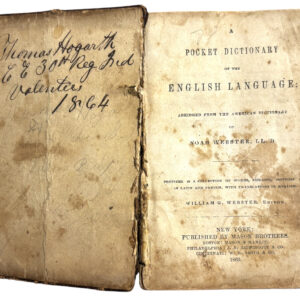

Civil War Soldier’s Pocket Dictionary Id’d to Lt. Thomas Hogarth Co. E 30th Indiana Infantry

$325Civil War Soldier’s Pocket Dictionary Id’d to Lt. Thomas Hogarth Co. E 30th Indiana InfantryMay 26, 2025 -

Superb Unworn Group of Civil War Medical Officer’s / Colonel’s Shoulder Boards and Dress Epaulette Insignia in the Original Horstmann and Allien Box

$1,950Superb Unworn Group of Civil War Medical Officer’s / Colonel’s Shoulder Boards and Dress Epaulette Insignia in the Original Horstmann and Allien BoxMay 25, 2025 -

Civil War Union Infantry Officer’s Rare Sky-Blue Vest

$3,350Civil War Union Infantry Officer’s Rare Sky-Blue VestMay 24, 2025 -

1825 – 1830 Watercolor of a British Rifleman

$7501825 – 1830 Watercolor of a British RiflemanMay 19, 2025 -

Extremely Rare Civil War Signal Corps Officer’s Hat Badge

$3,950Extremely Rare Civil War Signal Corps Officer’s Hat BadgeMay 14, 2025 -

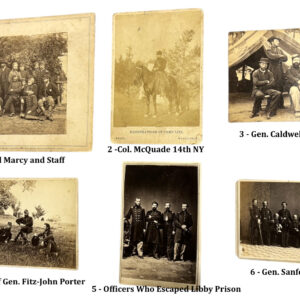

Group of Identified Civil War CDVs

Group of Identified Civil War CDVsMay 13, 2025 -

Original Civil War Model 1858 Infantry or Dismounted Enlisted Man’s Greatcoat

$4,500Original Civil War Model 1858 Infantry or Dismounted Enlisted Man’s GreatcoatMay 3, 2025 -

Civil War U.S. Ordnance Officer’s Dress Epaulettes in Original Jappaned Tin Case

$950Civil War U.S. Ordnance Officer’s Dress Epaulettes in Original Jappaned Tin CaseApril 27, 2025 -

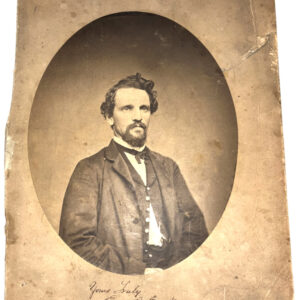

Large Id’d Albumen of a Civil War Navy Engineer on the Steam Sloop USS Richmond -Emo(e)ry J. Brooks – Image by Famed Phila. Photographer Frederick Gutekunst – Image Dated 1862

$450Large Id’d Albumen of a Civil War Navy Engineer on the Steam Sloop USS Richmond -Emo(e)ry J. Brooks – Image by Famed Phila. Photographer Frederick Gutekunst – Image Dated 1862April 26, 2025 -

Veteran’s Escutcheon in Original Frame – Lt. Charles H. Fasnacht – Medal of Honor Winner 99th Pa. Infantry

$750Veteran’s Escutcheon in Original Frame – Lt. Charles H. Fasnacht – Medal of Honor Winner 99th Pa. InfantryApril 21, 2025