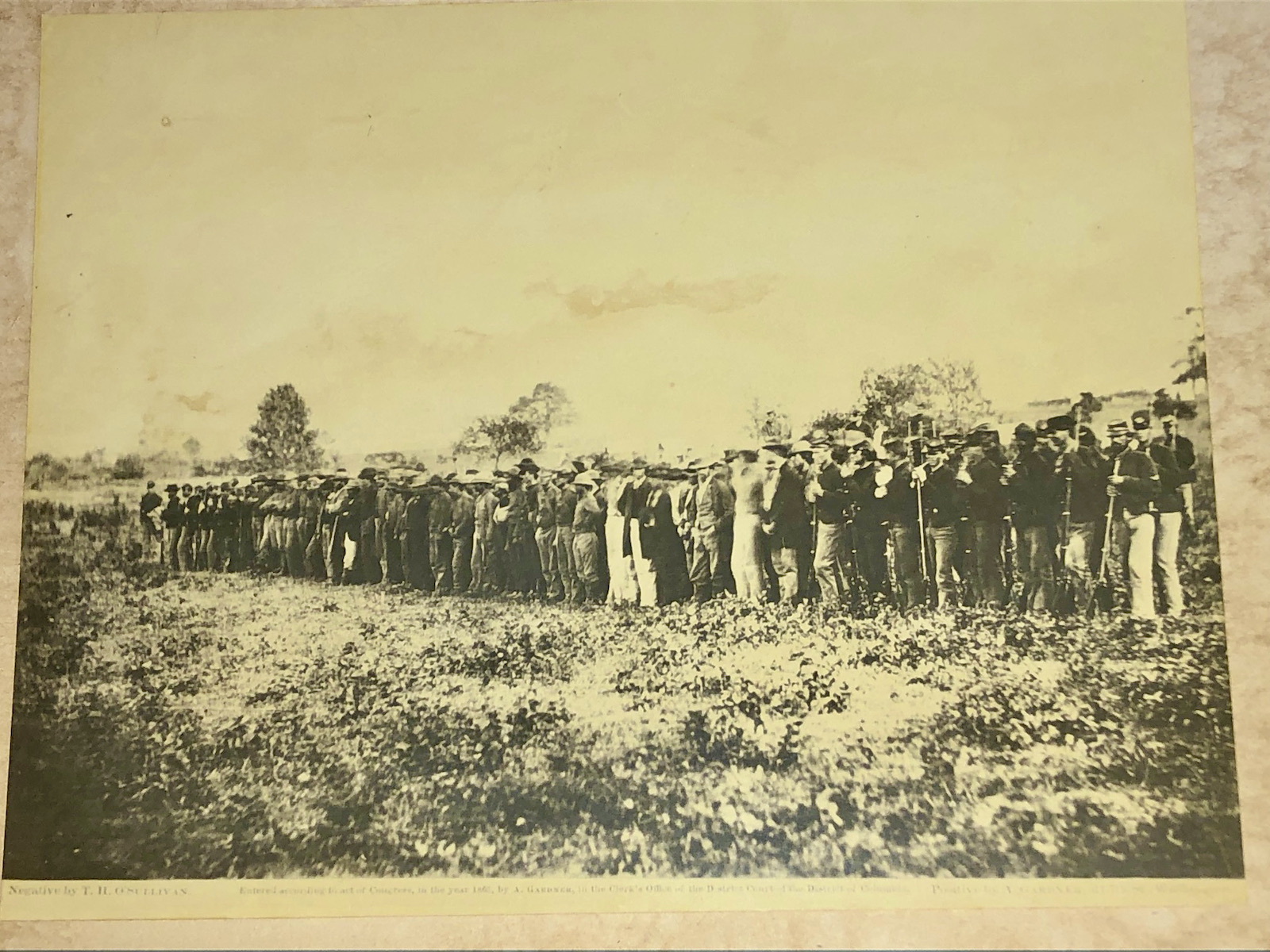

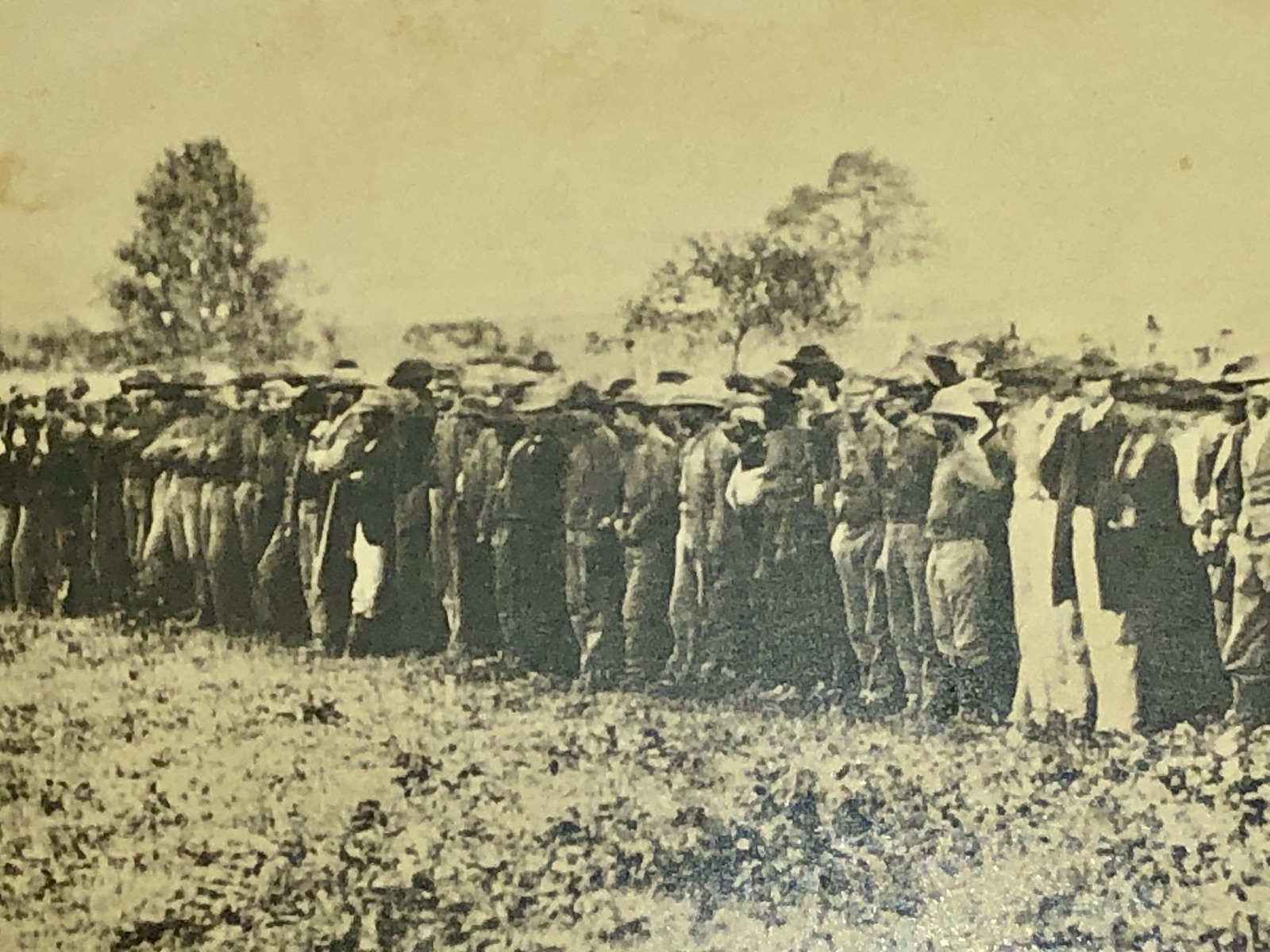

Albumen Image of a Group of Confederate prisoners at Fairfax Courthouse – Negative by T.H. O’Sullivan; Positive by A. Gardner

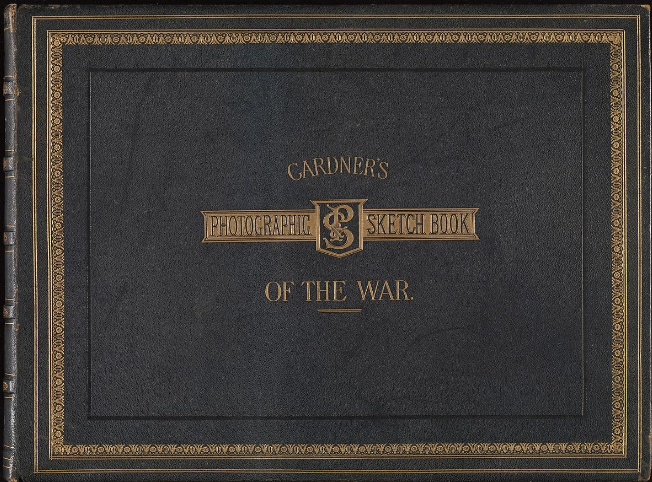

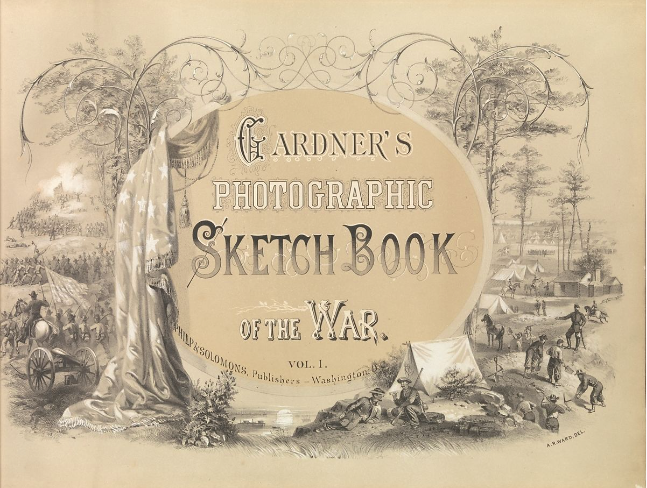

Albumen Image of a Group of Confederate prisoners at Fairfax Courthouse – Negative by T.H. O’Sullivan; Positive by A. Gardner – This photograph of Confederate prisoners appears in the two-volume opus “Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1865-66)”. Gardner was offended by Matthew Brady’s habit of obscuring the names of his field operators with the deceptive credit “Brady“. In his renown photographic compendium of large, Civil War images, besides titling each plate, Gardner took pains to specifically identify each of the eleven photographers in his publication; forty-four of the one hundred photographs are credited to Timothy O’Sullivan. This striking image of Confederate prisoners at Fairfax Courthouse, in northern Virginia, appears in Gardner’s photographic sketch book, published in 1866, in Washington, [D.C.], by Philp & Solomons, [1865-66], v. 1, no. 34. This albumen is mounted on original, period cardstock and remains in excellent condition. We presume that this is a second generation of the image, from O’Sullivan’s original glass negative. The image is mounted, as most period albumens, on cardstock; the latter is in good condition, with some obvious water stains on the back, opposite the image. The image proper, as mentioned, remains in excellent condition. Beneath the image is printed the following:

“Negative by T.H. O’SULLIVAN / Entered according to the act of Congress, in the year 1865, by A. Gardner, in the Clerks’ Office of the District Court of the District of Columbia / Positive by A. GARDNER 311 7th St. Washington.”

Beside this plate (no. 34 in Gardner’s book) is the following description, composed by Alexander Gardner:

“These were a batch of rebel cavalrymen, captured in the battle of Aldie, by the troops under Gen. Pleasanton. The majority of them are dressed in the dusty grey jacket and trousers, and drab felt hat usually worn by the rebel cavalry; some, however, show no change from the ordinary clothes of a civilian, being probably recruits or conscripts, although their appearance laid them open to the charge (often made during the war) of being irregulars, out for a day’s amusement, with their friends in the cavalry, as one might go off for a day’s shooting. The fight in which they were taken, was hotly contested, and took place at the foot of the upper end of the Bull Run range of hills, in Loudoun County, in and around the village of Aldie. The rebels were driven, and our cavalry left masters of the field – not without serious loss to our side, as well as to the enemy – a day or two after, Pleasanton attacked and drove them fifteen miles across the country, to the refuge of the Blue Ridge. Generals Buford and Gregg, ably leading their divisions in the fight.

The country around Aldie is very charming, very much diversified with hill, wood and valley, fine farms, pretty brooks – with stone bridges – and beyond all, the noble chain of the Blue Ridge, dividing Loudoun from the Shenandoah Valley.”

Measurements: Cardstock – W – 14”; H – 11”; Albumen – W – 9.25”; H – 7”

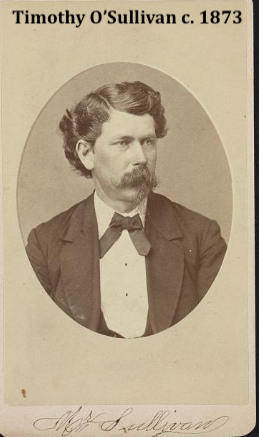

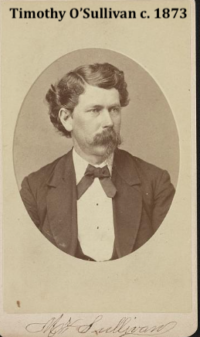

Timothy O’Sullivan

Timothy H. O’Sullivan was born in Ireland, in 1840; he emigrated to the United States, at a young age, to Richmond County, New York. O’Sullivan began his photography career as an apprentice in Mathew Brady’s Fulton Street gallery in New York City and then moved on to the Washington, D.C., branch managed by Alexander Gardner. In 1861, at the age of twenty-one, O’Sullivan joined Brady’s team of Civil War photographers. When Gardner left Brady, O’Sullivan went with him, working for Gardner until the end of the war. Several of his images were included in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War. O’Sullivan built his reputation on images that conveyed the destructive power of modern warfare. His photographs of Forts Fisher and Sedgwick suggest the dismal psychological as well as physical effect of continual barrages of distant cannon fire on the soldiers behind the barricades.

In 1867 O’Sullivan joined Clarence King’s geological survey of the fortieth parallel — the first federal expedition in the West after the Civil War. The letter of authorization, dated March 21, 1867, from Brigadier General A. A. Humphreys, chief of engineers, Department of War, charged King “to direct a geological and topographical exploration of the territory between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada Mountains, including the route or routes of the Pacific railroad.” O’Sullivan was strongly influenced by King’s interest in the arts (he was a member of the Ruskinian group, the Society for the Advancement of Truth in Art), as well as by contemporary science and its attendant controversies. His work for the King survey often functioned as both objective scientific documentation and a personal evocation of the fantastic and beautiful qualities of the western landscape.

In 1871 O’Sullivan joined the geological surveys west of the one hundredth meridian, under the command of Lieutenant George M. Wheeler of the U.S. Corps of Engineers. An army man rather than a civilian scientist like King, Wheeler insisted on a survey that would be of practical value. His reports included information likely to be useful in the establishment of roads and rail routes and the development of economic resources. Wheeler’s captions for O’Sullivan’s pictures provide geological information but also emphasize that the West was a hospitable place for settlers. For example, he compared Shoshone Falls favorably to Niagara Falls, the most popular American symbol of nature’s grandeur. Indeed, O’Sullivan’s 1874 image of Shoshone Falls, a version of a nearly identical image of the falls he made for King six years before in 1868, emphasized perspective as picturesque as it was dramatically precipitant.

Flat-bottomed boats were used to go up the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon to the mouth of Diamond Creek. O’Sullivan commanded one of the boats, which he christened The Picture. Many of his negatives on glass plates were lost in transport, but surviving views of the Colorado’s canyons are among his finest.

In 1873 O’Sullivan led an independent expedition for Wheeler, visiting the Zuni and Magia pueblos and the Canyon de Chelly, with its remnants of a cliff-dwelling culture. O’Sullivan’s 1873 images of Apache scouts are among the few unromanticized pictures of the western Indian, unlike those of many ethnographic photographers who posed Indians in the studio or outdoors against neutral backgrounds.

O’Sullivan died in New York City, in 1882.

Merry A. Foresta American Photographs: The First Century (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996)

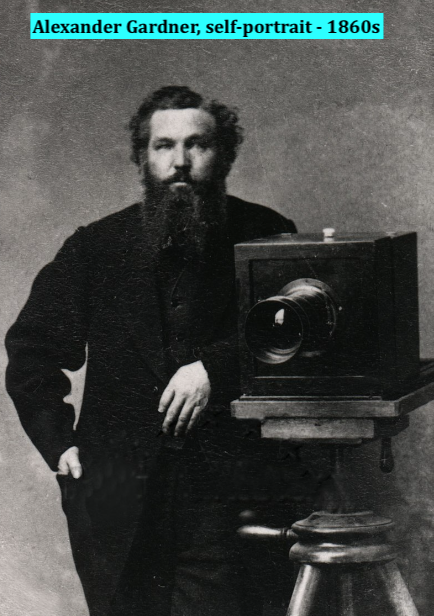

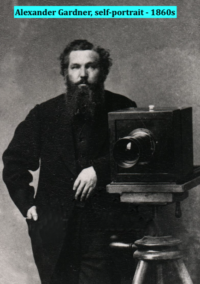

Alexander Gardner (October 17, 1821 – December 10, 1882) was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the American Civil War, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and of the conspirators and the execution of the participants in the Lincoln assassination plot.

Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, published in 1866, was the first photographically illustrated book on the American Civil War. It is a cornerstone of photography books, and within those books produced in America, it is peerless.Gardner’s Sketch Book was published in two volumes, with fifty hand-mounted albumen photographs in each book. A page of text written by Alexander Gardner accompanied each photograph. Although primarily a picture book, its text was an integral element of the overall presentation. For each print, Gardner carefully attributed the maker of the negative and the positive. The book tells the story, primarily of the eastern theater, of the war as conceptualized by Gardner. The selection and sequencing of the photographs, authorship of the text, and marketing of the book at the princely sum of $150 was all the genius of Alexander Gardner. Since it was a commercial failure, maybe the price wasn’t genius—but the book certainly was. The book covers the basics of how Civil War photographers operated in the field. It discusses the complexity of the photographic process and compares the role of the photographer with that of the sketch artist, who was also making a record of the war. It analyzes how sketch artists realize their imagery as opposed to how the photographer realizes his. While the technical limitations prevented the recording of actual battle scenes, photography could preserve in minute detail what a scene looked like where an awful occurrence had taken place. Today these qualities of photography are well-known, but at the time they were new concepts. Gardner photographed Lincoln more than twice as many times as any other photographer and made some of the most memorable, graceful poses of the president.