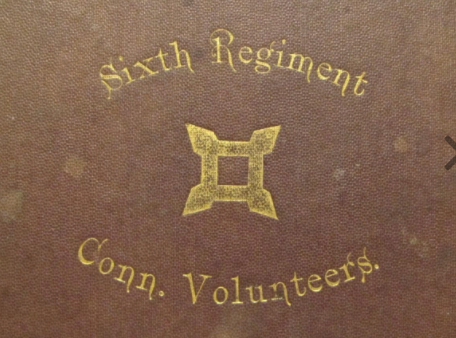

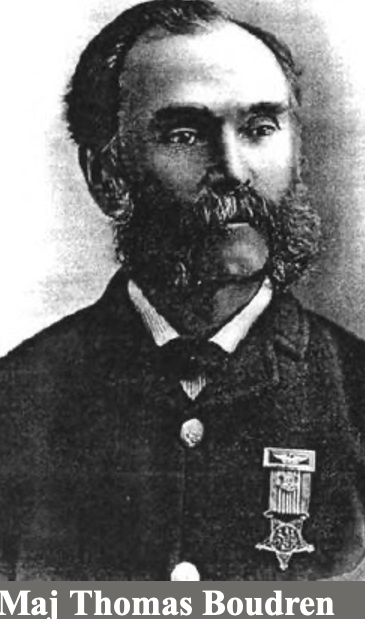

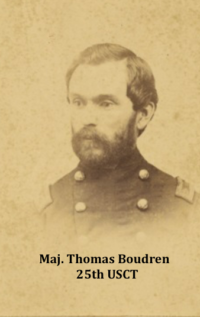

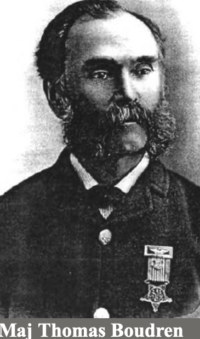

Id’d Civil War Officer’s Sash – Major Thomas Boudren 6th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry

SOLD

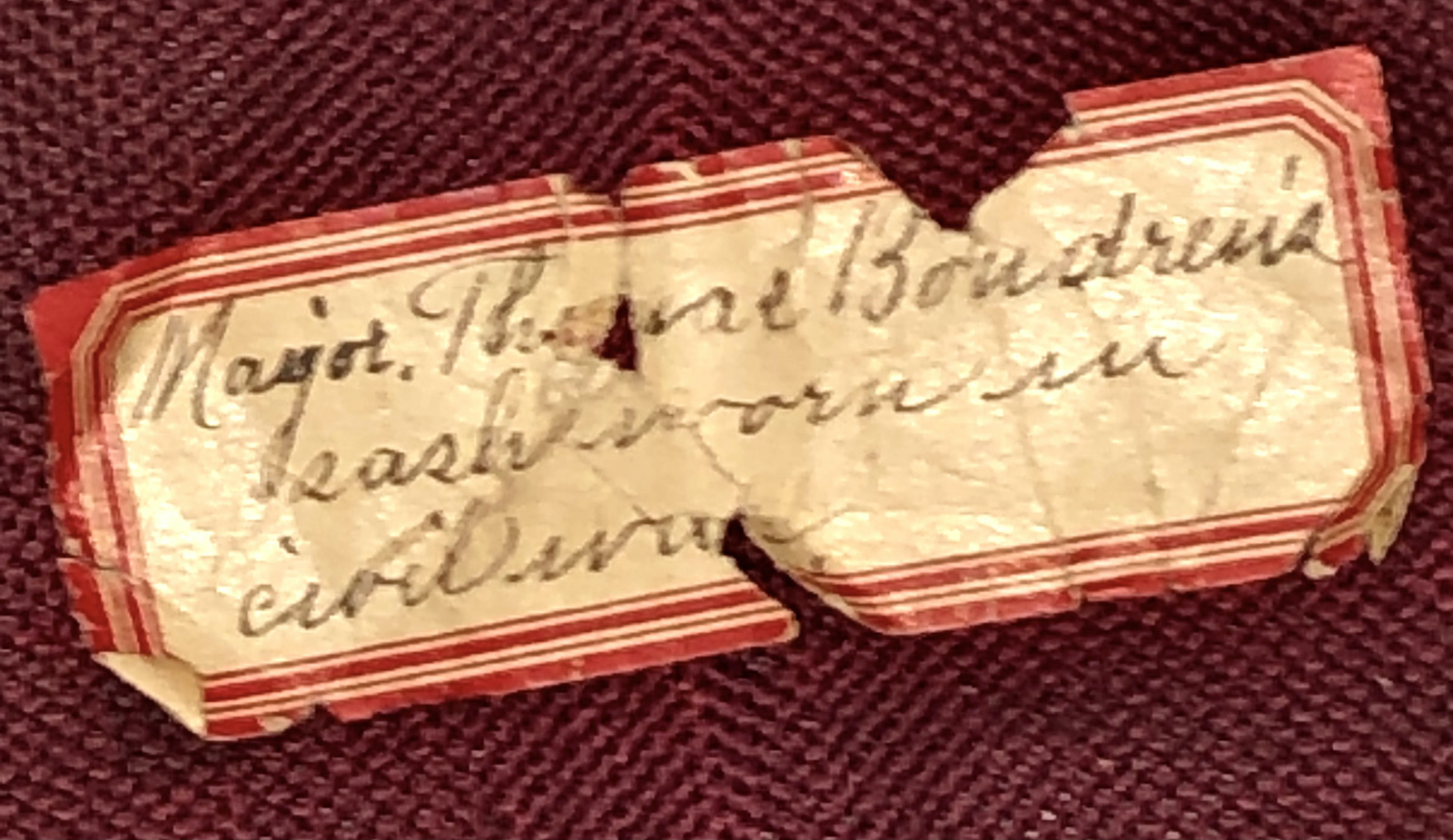

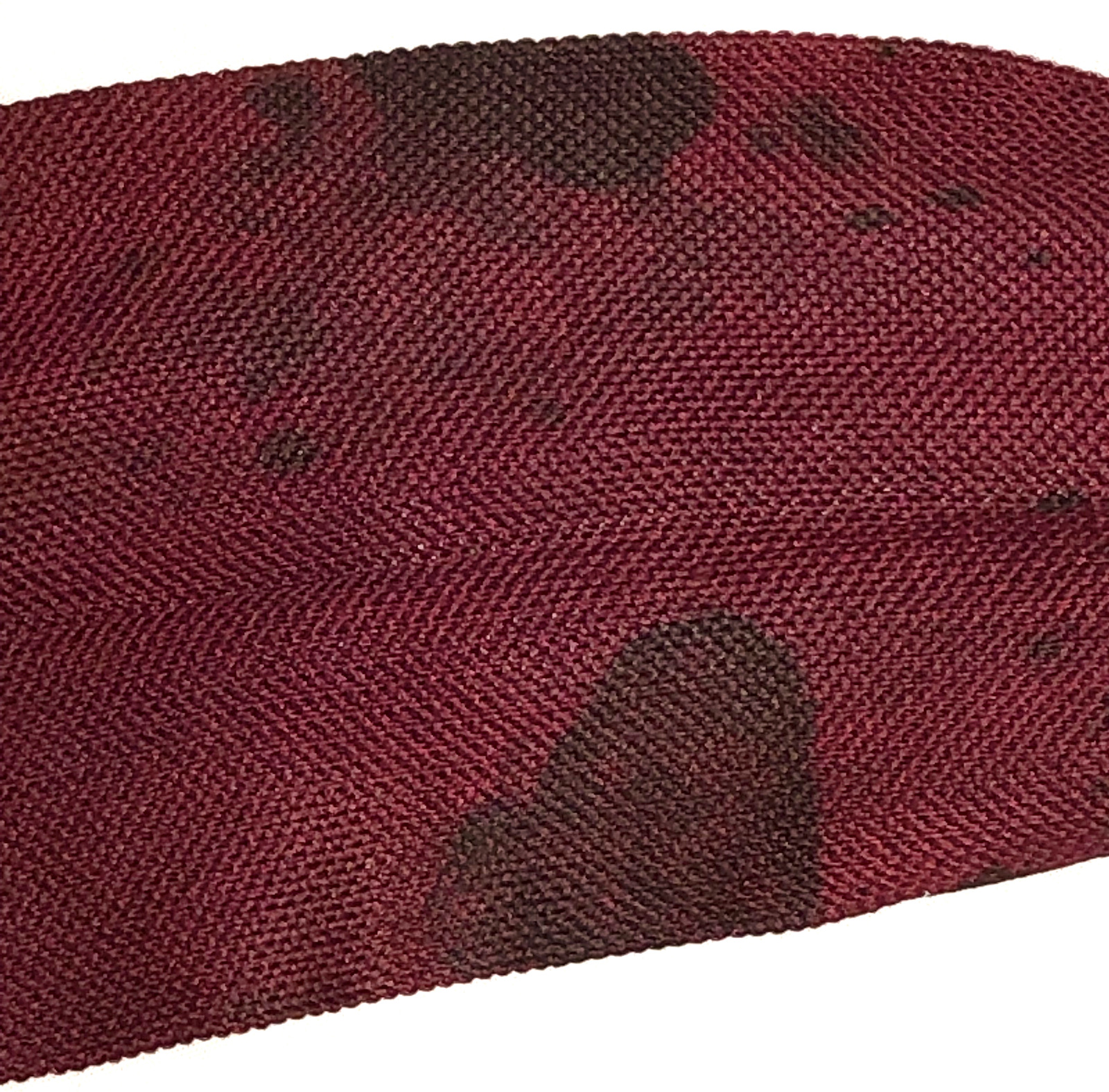

Id’d Civil War Officer’s Sash – Major Thomas Boudren 6th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry – This Civil War officer’s sash is a typical style, Union officer’s, silk sash; it is approximately 82” in length and remains in excellent condition, with both end knots and attached fringe in place; there are no tears or loss in the body of the sash, and the color remains strong. Attached to the sash is an old, gummed label, perhaps from a small, local museum or GAR hall, that states the following:

“Major Thomas Boudren’s

sash worn in

civil war”

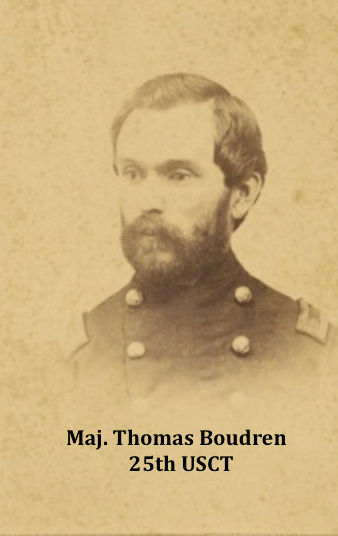

Thomas Boudren enlisted in August of 1861 and was commissioned, shortly thereafter, on September 5, 1861, as a Captain, in Co. I of the 6th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry; Boudren was discharged from service in the 6th CT, on January of 1864 and was promoted to the rank of Major in the newly formed, 25th USCT infantry regiment. During Boudren’s years of service, in the 6th Connecticut, the regiment was engaged principally in the South Carolina; Boudren and the 6th would see action in the Battles of Pulaski, Secessionville and Pocotaligo; on July 18, 1863, the 6th Connecticut would lead the assault, from the seaside, on Battery Wagner, on Morris Island, suffering significant casualties, to include several high ranking officers; the 6th actually breached Wagner’s ramparts and held a small corner of the fort for a brief period. Captain Boudren, was directly involved in this difficult engagement, and his sash, perhaps as result of assisting wounded comrades, is distinctly blood stained in two or three places. The sash remains in its original full length of 82 inches.

Thomas Boudren

| Residence Bridgeport CT; Enlisted on 8/25/1861 as a Captain. On 9/5/1861 he was commissioned into “I” Co. CT 6th Infantry He was discharged on 1/14/1864 |

6th CT Infantry

( 3-years )

| Organized: New Haven, CT on 9/12/61 Mustered Out: 8/21/65 at New Haven, CTOfficers Killed or Mortally Wounded: 8 Officers Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 4 Enlisted Men Killed or Mortally Wounded: 99 Enlisted Men Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 124 (Source: Fox, Regimental Losses) |

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comment |

| Oct ’61 | Apr ’62 | 3 | South Carolina Expeditionary Corps | |||

| Apr ’62 | Jul ’62 | 1 | 1 | Department of the South | ||

| Jul ’62 | Sep ’62 | Dist of Beaufort | Department of the South | |||

| Sep ’62 | Mar ’63 | US Forces, Beaufort | 10 | Department of the South | ||

| Apr ’63 | Apr ’63 | US Forces, Hilton Head | 10 | Department of the South | ||

| Apr ’63 | Jun ’63 | US Forces, Folly Island | Department of the South | |||

| Jun ’63 | Jul ’63 | 2 | US Forces, Folly Island | Department of the South | ||

| Jul ’63 | Jul ’63 | 2 | 2 | 10 | Department of the South | |

| Jul ’63 | Jul ’63 | 1 | US Forces, Morris Island | 10 | Department of the South | |

| Jul ’63 | Apr ’64 | US Forces, Hilton Head | 10 | Department of the South | ||

| Apr ’64 | May ’64 | 3 | 1 | 10 | Army of the James | |

| May ’64 | Dec ’64 | 2 | 1 | 10 | Army of the James | |

| Dec ’64 | Jan ’65 | 2 | 1 | 24 | Army of the James | |

| Jan ’65 | Mar ’65 | 2 | 1 | Terry’s Provisional | Department of North Carolina | |

| Mar ’65 | Apr ’65 | 2 | 1 | 10 | Department of North Carolina | |

| Mar ’65 | Jul ’65 | Abbott’s Detached | 10 | Department of North Carolina | Mustered Out |

CONNECTICUT

SIXTH REGIMENT C. V. INFANTRY.

(Three Years.)

| WRITTEN BY CHARLES K. CADWELL, LATE SERGEANT OF COMPANY F,

SIXTH CONNECTICUT VOLUNTEERS.

THE Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers was organized August, 1861, under the efficient leadership of Colonel John L. Chatfield, and was the third regiment furnished by the State of Connecticut under the first call of the President for volunteers for three years. Its companies were organized in the following localities: Company A, Putnam; Company B, Hartford; Companies C, F, and K, New Haven; Company D, Stamford; Company E, Waterbury; Company G, New Britain; Companies H and I, Bridgeport. It encamped at Oyster Point, New Haven, and was mustered into the State service September 3, 1861, and into the United States service September 12th.

On September 17, 1861, the regiment, numbering one thousand and eight (1,008) officers and men, left New Haven for the seat of war, and arrived at Washington, D. C., September 19th, where it encamped on Meridian Hill, and was brigaded with the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers and Third and Fourth New Hampshire Volunteers, under command of Brigadier-General H. G. Wright, afterwards commander of the Sixth Army Corps.

The twenty days of camp life here was a period of unceasing drill and discipline, only broken by a visit to the camp of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, upon a tour of inspection.

October 8, 1861, the regiment left Washington for Annapolis, Md., where it joined the forces then being organized under Gen. W. T. Sherman of the army, and Admiral Dupont of the navy, for an expedition to the Southern coast. On October 19th, this expedition, being then the largest land and naval expeditionary force of modern ages, in number of naval vessels and troops, sailed from Annapolis, encountering a terrific storm off Cape Hatteras, which disabled and wrecked a number of the vessels, and arrived off Port Royal, S. C., Nov. 5, 1861. On the 7th of November the bombardment of Forts Walker and Beauregard in the harbor, and the battle between the Union and Confederate naval forces, being the first naval engagement of the war, took place in full view of the regiment, which was in the advance to land as soon as the forts were reduced. The engagement lasted five hours, and at its close, the regiment, with the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers, landed in small boats, and, taking possession of the forts, immediately pushed forward after the flying enemy, and drove them from the island, capturing a number of prisoners.

For some months the time was occupied in building fortifications, and in making raids upon the surrounding country, in which a large quantity of supplies was captured.

In January, 1862, the regiment took part in an expedition to capture Savannah, Ga., by the way of Warsaw Sound, Ga. The attempt was a failure, and in consequence of the regiment being kept on a small, over-crowded vessel sixteen days without cooked food, with no vegetables, with hard-tack full of vermin, and water that was stored in kerosene-oil barrels, and without sufficient room on the vessel for all of the men to lie down at once, spotted fever broke out in the regiment, and many lives were unnecessarily lost.

On March, 1862, the regiment was a part of the force engaged in the siege and capture of Fort Pulaski, on Savannah River, Ga., its more particular operations in the siege being the construction and maintenance of a battery upon Jones Island, which was between the fort and the city of Savannah, for the double purpose of preventing reinforcements reaching the fort, and to prevent the rebel iron-clad “Atlanta” from passing down the river. As the island was covered with water at high tide, the duty was laborious as well as dangerous, and many of the men suffered from disease and hardship. On April 11, 1862, Fort Pulaski surrendered, and the regiment returned to pleasant quarters on Dawfuski Island.

In June, 1862, the regiment took part in the expedition against Charleston, S. C., under General Hunter, marching over Jones Island, and suffering many hardships, being three days without food, as the wagon trains were cut off, but finally arriving at James Island, where, on the 10th of June, they were engaged in a skirmish, and on the 16th of June, 1862, took part in the battle of Secessionville, S. C., after which they went into camp at Beaufort, S. C., and performed picket and guard duty until October 22, 1862, when they were engaged in the battle of Pocotaligo, S. C., in which the regiment suffered its first large loss in battle, the casualties being thirty-eight killed and wounded. Among the severely wounded were Colonel Chatfield, who was then commanding the brigade, and Lieutenant- Colonel John Speidel commanding the regiment.

The following-named members of the regiment were honorably mentioned, for bravery in this battle, by the commander of the department, in his report to the War Department:* Lieutenant S. S. Stevens, Company I; Commissary-Sergeant William H. Johnson; Sergeant Charles H. Grogan, Company I; privates Robert Wilson, Company D, Granville Platt and Alfred B. Beers, Company I.

The Sixth returned to Beaufort after this engagement, from which place they were transferred, March 18, 1863, to Jacksonville, Fla. Here they fortified the town, and defended it against the attacks of the enemy, performing duties that were dangerous and harassing in the extreme.

About April 1, 1863, the regiment left Jacksonville, and after a short tour of duty at Hilton Head, Beaufort, and some scouting upon the islands along the coast, were landed, about May 1st, on Folly Island, S. C., to engage in the second attack on Charleston and Fort Sumter, by the way of Morris Island. The regiment worked nights for three weeks in constructing fortifications, during which time they and the remainder of the brigade built ten batteries and mounted forty-eight heavy siege-guns in them, within four hundred yards of the enemy’s works on Morris Island, without being discovered.

At midnight of July 9th, the regiment, with other forces under General Strong, ascended Folly River in boats, and at daybreak on the 10th, after a desperate resistance, and under a galling fire, effected a landing on Morris Island in the face of the enemy’s guns, and charged and carried the fortifications, capturing during the day 125 prisoners and two battle-flags, one of which was taken by Roper Hounslow, of Company D, the rebel standard-bearer losing his life in the attempt to save his flag. The regiment was at the front during the whole day, but lost only ten men.

On July 18, 1863, the Sixth led the charge upon the sea face of Fort Wagner. In this charge Colonel Chatfield, who resigned command of a brigade to lead his regiment, received his death-wound, and Lieutenant S. S. Stevens was killed, and Lieutenants West and Kost were taken prisoners. Color-Sergeant Gustave DeBonge was killed, also six others who took the colors one after the other, and Captain F. B. Osborn finally rescued and saved the flag. The Sixth, almost unaided, held an angle of the fort for about three hours, but not being supported, was compelled to retire, a portion of the regiment being captured. The regiment took into the charge about four hundred men, and its loss was about one hundred and forty, or thirty-five per cent, of the number engaged.

Of the conduct of the Sixth Connecticut Volunteers in this engagement, Paul H. Hayne, a Southern writer upon the siege of Wagner in the March, 1886, “Southern Bivouac,” says:–

“Then a grand deed, what the old Northmen would have called a deed of ‘derring-do,’ was performed by men of the ever-dominant Caucasian race, the thought of which, as I write, a quarter of a century after its occurrence, here in the tranquil Indian summer, makes my heart beat and pulses throb tumultuously. Across the narrow and fatal stretch before the fort, every inch of which was swept by a hurricane of fire, a besom of destruction, the Sixth Connecticut, Colonel John L. Chatfield, charged with such undaunted resolution upon the southeast salient, that they succeeded, in the very face of hell, one may say, in capturing it.

“What though their victory was a barren achievement? What though for three hours they were penned in, no support daring to follow them? Friend and foe alike now, as then, must honor and salute them as the bravest of the brave.

“The history of the war, rife with desperate conflicts, can show no more terrific strife than this. It was, in more than one particular, a battle of giants.”

The losses in this action were so great that the regiment was sent to Hilton Head to recuperate. Colonel Chatfield died of his wounds, and Lieutenant-Colonel Speidel, by reason of his wounds, was transferred to the Invalid Corps. During the fall and winter of 1863, many of the men re-enlisted, and the regiment was engaged in routine duty. Adjutant Redfield Duryee was promoted to be Colonel.

In April, 1864, the regiment was transferred to Virginia, and took part in the campaign of that year, being in the command of General Butler. May 9th, it was engaged in the action at Chester Station on the Petersburg road, and again on May 10th, at the same place. On May 16th it was engaged in the battle of Drewry’s Bluff on Proctor’s Creek, and on May 20th and June 2d in skirmishes at Bermuda Hundred. May 27th Colonel Duryea resigned, and subsequently Alfred P. Rockwell, Captain of the First Connecticut Light Battery, was promoted Colonel, and proved to be a brave and capable officer.

On June 9th the regiment took part in the attack on Petersburg, Va., under General Gilmore.

June 17th the regiment advanced from Bermuda Hundred and tore up the Petersburg railroad, but was attacked by General Lee’s army, which was on its way to Petersburg to defend that point against General Grant, and driven back to the intrenchments again.

The losses of the regiment in the several engagements referred to, from May 10th to June 18th inclusive, were 184 officers and men.

June 25th the regiment crossed the James River and covered the movement of General Sheridan, who was returning turning from his famous raid around Richmond.

From June 25th to August 13th the Sixth was in the intrenchments at Bermuda Hundred, doing picket duty and guarding the line. August 14th the regiment crossed the James River to Deep Bottom, and was engaged in the battle of Strawberry Plains, capturing two lines of earthworks. August 16th it was engaged in the battle of Deep Run, capturing a line of earthworks, two hundred prisoners, and two stands of colors, and lost five killed, sixty-nine wounded, and eleven missing. The regiment was then ordered to Petersburg, and was engaged in the siege of that place, at the front of the line, until September 27th, during which time it performed picket duty, and also built Fort Haskell, one of the largest and strongest forts upon the line. Sleeping here was principally done in holes in the ground, and the luxury of a cooked meal of victuals was not often enjoyed, while the appearance of a head over the breastworks was an invitation to every man on the line to shoot. The exposure and hardships upon the Petersburg line involved more danger than a pitched battle, as it was a continuous skirmish, night and day.

The term of three years having expired, the men who did not re-enlist were discharged in front of Petersburg, September 11, 1864, and were received with civic and military honors at New Haven.

September 28, 1864, the regiment marched to the north side of the James River, and was engaged in the battle of Fort Harrison and Newmarket Road, at Chapin’s Farms, and advanced up the Darbytown Road to within three miles of Richmond. October 1st the regiment was again engaged in a skirmish on the Darbytown Road at Laurel Hill Church. October 7th the enemy made an attack on the lines at Newmarket Road, the brunt of the battle falling upon the division with which the Sixth was connected, and upon that regiment first. Although twice assaulted by the enemy, both attacks were repulsed and the enemy driven from the field. October 13th the regiment was engaged at Darbytown Road, and October 27th at the Charles City Road.

Owing to fears of mob violence in the presidential election of November, 1864, the Sixth regiment, with many others, was ordered to New York by boat, and the vessels conveying them were stationed at different points on the East and North Rivers. After the election was over, the men, although within a few miles of home and loved ones, were not permitted to visit them, but were returned to their camp at the front.

After this, the time was spent in camp and picket duty until the latter part of December, 1864, when the regiment was ordered to take part in the second attack upon Fort Fisher, N. C., and accompanied General Terry upon that expedition, witnessing the greatest bombardment of modern ages, and participating, on January 16, 1865, in the greatest and most successful assault upon a well-defended fortification made during the war. After the capture of Fort Fisher the regiment took part in the operations for the capture of Wilmington, N. C., and the opening of a base of supplies for Gen. W. T. Sherman in North Carolina. These operations were, a skirmish on January 19, 1865, and the engagements near Fort Fisher, capture of Wilmington, and skirmish at Northeast Branch of Cape Fear River, February 22, 1865.

It was then engaged in garrison duty at Wilmington, N. C., along the line of the Wilmington & Weldon railroad, and at Goldsboro, N. C., until August; and was finally mustered out at New Haven, Conn., August 21, 1865.

The regiment served in the District of Columbia, and in the States of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. It was attached to the Tenth army corps, and for a short time to the Twenty-third corps and Twenty-fourth corps.

Two hundred and five (205) of its original members re- enlisted as veterans. Six hundred (600) recruits were credited to it. Add to these the one thousand and eight who went into the field originally, and we have an aggregate of one thousand eight hundred and thirteen men who have served with the regiment.

*See page 152, Vol. xiv, Records of War of the Rebellion.

ENGAGEMENTS.

Bombardment and Capture of Port Royal, S. C., Nov.7, 1861. Siege of Fort Pulaski, Ga., March 20 to April 11, 1862. James Island, S. C., July 10, 1862. James Island, Secessionville, July 16, 1862. Pocotaligo, S. C., Oct. 22, 1862. Morris Island, S. C., July 10, 1863. Fort Wagner, S. C., July 18, 1863. Chester Station, Va., May 10, 1864. Proctor’s Creek, Va., May 14, 1864. Drewry’s Bluff or Proctor’s Creek, Va., May 16, 1864. Near Bermuda Hundred, Va., May 20, 1864. Near Bermuda Hundred, Va., June 2, 1864. Petersburg, Va., June 7, 1864. Near Bermuda Hundred, Va., June 17, 1864. Deep Bottom, Va., Aug. 14 and 15, 1864. Deep Run, Va., Aug. 16, 1864. Siege of Petersburg, Va., August and September, 1864. Chapin’s Farms, Va., Sep. 29, 1864. Near Richmond, Va., Oct. 1, 1864. Newmarket Road, or Laurel Hill, Va., Oct. 7, 1864. Darbytown Road, Va., Oct. 13, 1864. Charles City Road, Va., Oct. 27, 1864. Fort Fisher, N. C., Jan. 15, 1865. Near Fort Fisher, N. C., Jan. 19, 1865. Near Fort Fisher, Capture of Wilmington, N. C., and Northeast Branch Cape Fear River, N. C., Feb. 21 and 22, 1865.

Source: Connecticut: Record of Service of Men during War of Rebellion |

THE

Old Sixth Regiment,

ITS

WAR RECORD, 1861-5,

BY

CHARLES K. CADWELL,

Late Sergeant of Co. F.

NEW HAVEN, CONN., 1875.

NEW HAVEN:

TUTTLE, MOREHOUSE & TAYLOR, PRINTERS.

1875.

TO

THE LOYAL WOMEN,

WHOSE

HUSBANDS, BROTHERS AND FRIENDS

CAST THEIR LOT WITH THE OLD SIXTH

IN

DEFENCE OF THE FLAG,

THIS MEMORIAL OF PATRIOTIC SERVICE IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED

By the Author.

CHAPTER V.

About the 1st of July large numbers of troops began to arrive at the island, and “old Folly” literally swarmed with them. The order was given for us to capture the battery on the end of Morris Island, and we expected to make a night attack, so we sewed pieces of white cotton cloth on the left arm, that we might be distinguished from the foe. At midnight on the 9th, large detachments of troops stepped quietly into boats and rowed silently up Folly River; not a word was spoken above a whisper, nor any noise heard, save the splashing of the oars and the occasional plunge of the alligators from the river bank. At about 3 o’clock the flotilla of eighty large launches had arrived near Morris Island, and we were ordered to keep close to shore and under cover of the tall sea grass that lined its banks. Here we waited patiently for the dawn of day,–a day that was to bring victory to our flag, but death to many a brave soldier. We could see from our position the rebel soldier lazily walking his beat on the parapet, while the smoke from the dim camp fires slowly ascended skyward. Everything indicated to us that they were not expecting cannon balls for breakfast nor the advent of the boys in blue. Gen. Strong, who was to lead the attack, looked every inch a soldier, as he moved among us giving cheering words to all. At precisely 5 o’clock, the batteries that we had worked on so faithfully for weeks, were unmasked to the enemy and opened simultaneously from 48 guns. The astonished rebels soon replied with great rapidity. As the ball opened, the inhabitants of Secessionville, on James Island, crowded to the roofs of the houses till they were black with them, to witness the battle. Our gunboats shelled the batteries with good effect, and the enemy discovering our position in the boats, scattered grape and cannister among us with fearful rapidity. There we lay in the boats for two hours under a heavy fire, while the rebels divided their compliments among us and the gunners at our batteries. The batteries did not seem to have the desired effect of dispersing the enemy, and Gen. Strong was signalled to land his forces and charge upon their works. The rebels perceiving the signal and interpreted its meaning, directed a galling fire at the boats. One boat of the Sixth was struck and a member of Co. “E” lost a leg which soon caused his death; another was wounded and the boat overturned, but was soon righted by help from others and the men rescued. We pulled for the shore, eager to land, and while a detachment of the Seventh Connecticut landed first on the left of the rifle pits and were feeling their way. The old Sixth sprang into the water knee deep and was soon directly in front of their battery; rushing forward with bayonets fixed and with an honest Union cheer. The rebels depressed their guns to rake us as we landed, but the shot struck the ground in front of us and passed over our heads, and the amazed rebels, seeing our determination, turned to flee just as we gained the first line of works, but we were too quick for them, and the Sixth captured 125 prisoners and a rebel flag. Private Roper Hounslow, of Co. “D,” saw the bearer of the flag making for the rear as fast as his legs could carry him, when he ordered him to halt; but he would not, and he shot him through the head. The flag was inscribed “Pocotaligo, Oct. 22, 1862.” It had blood stains upon it which were probably spilled at that place. Col. Chatfield waved the banner aloft, feeling very much elated to think we had captured the flag that bore this inscription, for he received a wound at Pocotaligo. Col. Chatfield led his men to the last range of rifle pits, which was within a rifle shot of Fort Wagner. The Sixth had the advance all day. Our flags were riddled with shell, and the staff of the stars and stripes was broken in three different places. A rebel ramrod was substituted for the broken staff, and our flags floated from the only house on the island. This house was the headquarters for the rebel officers, and when we entered it the coffee was in cups on the table and breakfast nearly ready; but we did not stop to eat, as we were looking for water; and seeing the coffee, disposed of it in short meter. Two solid shot from Fort Wagner came tearing through the house, demolishing the chimney and scattering the bricks upon the tables in great confusion. We concluded that we might be demolished if we remained in there long, so went out; the house being a good target, it was soon riddled with shell from Forts Sumpter and Wagner.

We remained at the front till about sunset, under a severe fire continually. Tired and footsore, with hardly anything to eat, and without sleep for three nights, we were glad when orders came for us to fall to the rear and another regiment to take our place. Gen. Strong was active all day and infused spirit into the soldiers by his commanding aspect. When we landed he was burdened with a pair of long military boots upon his feet, and as we jumped into the water these became so full that locomotion was well nigh impossible, so he pulled them off and threw them away, going in his stockings. The briars over the sand hills soon wore the bottoms of these off, and having captured a rebel mule, got astride of him and went forward with a cheer from the soldiers. Soon after the battle he appeared among the members of the Sixth, still astride the mule, who looked jaded enough. “Boys,” said he, “I don’t look like a General, but you look and have acted like true soldiers,” and immediately rode away, followed by the cheers of the soldiers.

It was determined to assault Fort Wagner and capture it with the bayonet. The Seventh Connecticut was to lead the charge, supported by the Ninth Maine and Seventy-sixth Pennsylvania. Early on the morning of the 11th, before the lark was awake, this command silently moved forward, drove in the rebel pickets and with a cheer rushed into the ditch and up the parapet, but met a very stubborn foe, who poured grape and cannister into their ranks. The Ninth Maine, instead of supporting them, wavered, at such a fearful fire, and ran away, while the Seventy-sixth Pennsylvania stood their ground. But the battle was against fearful odds, and they were obliged to retire and give up the contest. The Sixth lay all night in the rifle pits before Wagner, in a drenching rain, keeping a sharp look out for any surprise. On the morning of the 18th they came into camp wet and covered with sand, weary enough to lay up for a rest; but there is no rest for the soldier in time of war. Scarcely had we brushed off the sand and got a bite of pork and crackers before we were ordered to join in the assault on Wagner at dark. Never was an order more cheerfully obeyed, especially as the word passed around that Col. Chatfield was to lead us into action, the Colonel declaring his preference “to stand or fall with the men of the Sixth,” and refusing the honor of commanding our brigade, which belonged to him as the ranking officer. The gunboats shelled the rebel fort incessantly, plowing up great heaps of sand with one shell, and another perhaps would fill up the crevice. The broadsides from the New Ironsides were terrific, and the five monitors in line, together with five other gunboats, seemed to pour shell enough into Wagner to start several first class iron foundries. Shot and shell crashed above and within it and we wondered if half of them accomplished their mission. Before night came, hardly a gun boomed from Wagner, and many seemed to think an easy victory was within reach. As twilight approached the whole command lay under cover of the sand hills, waiting for the order to advance. The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts (colored regiment) were given the post of honor, the right of the first brigade, which position belonged to the Sixth; but at the request of Col. Shaw of the Fifty-fourth, who wanted the black troops to distinguish themselves, Col. Chatfield granted them their wish. Gen. Strong, who was to lead the charge, then addressed them. He said, “Men of Massachusetts, I am going to put you in front of the chivalry of South Carolina, and they will pour iron hail in your faces; but don’t flinch; defend the flag and uphold the honor of the State of Massachusetts.” He further told them “the Sixth Connecticut was immediately behind them, and I know they will not flinch.” They fell upon one knee in the sand and with their right arm raised, they swore they would do it.

The command formed silently on the beach; the men seemed impatient to move as the scene became exciting. “Close column, by companies,” was the order given, and the first brigade was off for its work. Steadily forward we moved, while the gunboats still roared away. At a given signal they ceased their fire and the order passed to charge. The rebels waited till we were within range and then poured a volley into our ranks from their guns on the parapet, while the riflemen rattled their bullets from the small arms. The Fifty-fourth wavered for a moment, and that moment was fatal to them; they broke and fled. On pressed the Sixth through the iron hail, picked our way through the abatis, descended the ditch and climbed up the steep sides of the fort, and gaining the parapet, was among the rebels. The flash of a thousand rifles poured into us, followed in quick succession by hand grenades. Shrapnel, cannister and grape were freely showered into the ranks, while we leaped down to the casemates and bomb-proofs, driving the enemy before us in great confusion. They entered their rifle pits and checked our further advance. The night was so dark it was hard to distinguish friend from foe, and a signal from the rebels turned the fire of Fort Sumpter and Battery Gregg upon the angle of the fort which we held. In vain did we look for help from the second brigade. Many a brave soldier had sealed his loyalty with his blood, and Gens. Strong and Seymour, Col. Chatfield and others, were badly wounded and carried to the rear. We were virtually without any commanding officer to lead us. To wait for daylight would have been sheer madness, and the supporting brigade, terrified by the deadly cannonade, instead of relying upon the bayonet to accomplish the work, stopped and fired. The rebels saw the mistake and rallied upon the Sixth, which stood almost alone within their works. The charge was repulsed, but after remaining for about three hours under such a deadly fire, we escaped as best we could, with terrible loss. Had the second brigade supported us in time, no doubt we could have held it. The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment rallied soon after they faltered and came up to the left angle of the fort, where they finally did good service. Here Col. Shaw met his death. The Sixth Regiment and the Connecticut colors were the first in the fort that night. The color-bearer, a German named Gustave DeBouge, was shot through the forehead while carrying the colors in the assault, and fell dead upon the flag, his life blood staining them through. Several brave ones who were near seized them, but they also fell either dead or wounded. Captain Frederick B. Osborn of Co. “K,” as brave an officer as ever wore shoulder straps, finally succeeded in pulling them from under the bodies and bearing them off in triumph. Our flags were much shattered and torn, but both were saved from the enemy.

In leaving Wagner that night, the ditch we crossed was filled with the dead and wounded, and we were compelled to step upon their bodies in making our escape. Many fell wounded upon the beach, and as the salt water surged over their bodies and in their wounds, their groans and cries were terrible to hear. Men begged piteously to others more fortunate, to remove them out of reach of the incoming tide. Our return to camp was attended with almost as much danger as our advance, and many brave men who were spared through the terrible ordeal in the fort, were either killed or wounded in returning to the rear. Every foot of ground seemed to be covered by the fire of the enemy’s guns. Batteries Gregg and Wagner, Forts Johnson, Ripley and Sumpter, besides two gunboats in the harbor, all directed their missiles of death to further our destruction while retreating; and how so many of us were spared through such a terrible conflict, can be attributed only to the goodness of our Heavenly Father. Truly the God of battles was on our side.

Our loss was quite heavy, considering the force engaged; the Sixth being exposed to the deadliest fire, their ranks were pretty well thinned out and the total figures footed up to 141 killed, wounded and missing. Many of the wounded brought off the field died the next day. Among the killed was Lieut. Stevens of Co. “I,” a cannister shot passing through his heart. He was Ass’t Adjutant General on Gen. Seymour’s staff, a position he filled with great ability. Having made military matters a study for a number of years his services were valuable to the government. His body was brought off the field and buried beneath one of the lone palmettos. A large influx of surgeons arrived from the North a few days after the battle, many of whom were mere boys, having hardly attained their majority, without experience, and many without common sense, came to Morris Island to assist in caring for the wounded. A slight wound in the limb was sufficient cause for them to amputate, and many suffered amputation of limbs that with proper treatment could have been spared to them. The writer saw a surgeon’s table improvised on a sand bluff, where these “would-be-surgeons” were using the scalpel knife in severing the arms and legs of the wounded, and a great pile lay beside them. Many a victim protested against this outrage, but was told that it was the only thing that would prolong life. The victims in many cases died soon after the operation.

Fatigue duty fell unusually hard upon the troops on the island, and every night found the Sixth in the trenches, building batteries or hauling heavy guns to the front. Under fire every day and night, the regiment suffered the loss of many members by wounds and death. While at the front one day a flag of truce came from Wagner, borne by a rebel Captain named Tracy. Capt. Tracy of the Sixth met him and found that he wanted to negotiate for an exchange of prisoners. Gen. Vogdes was informed and the terms agreed upon. On Friday, July 24, a large steamer bearing our wounded, came down the harbor and ran alongside of one of the monitors. It was said she was a blockade runner and had recently ran the blockade. Upon her decks were Englishmen dressed in the height of fashion, talking loudly of the superior intellect of the southern chivalry. The steamer Cosmopolitan, which had recently been fitted up as a hospital ship, ran alongside and delivered up the rebel wounded and the rebels gave us 205 Union soldiers. They also reported that they had amputated the limbs of 25 and that 50 had died on their hands. We also learned that they were so indignant because our government employed negro troops, that when they found Col. Shaw’s body they dug a deep trench and put the body in and then threw 25 dead negroes top of it. This circumstance we learned to be a fact, the pickets in our front having reported the same thing to us.

The Sixth Regiment, so shattered in the charge of the 18th and depleted in numbers, was ordered to Hilton Head to recruit and care for the large numbers who were wounded. We landed there on the 31st of July, commanded by Captain Tracy, who was senior Captain in the regiment and highest officer for duty. While at the Head the news came to us of the death of Gen. Strong and Col. Chatfield, both having gone North to recruit their health. The men of the Sixth cherished very great affection for their beloved Colonel, and were grieved to hear of his untimely death.

Col. Chatfield was born at Oxford, Conn., in 1826; was the son of Pulaski and Amanda Chatfield. He was apprenticed to the carpenter business in Derby, where he served four years at his trade; after which he worked as a journeyman. In 1855, having moved to Waterbury, he was associated with a brother in building, and the firm was widely and favorably known. Always upright, a man of sterling integrity, prompt and honorable in all his dealings, he possessed the confidence and esteem of all with whom he came in contact.

Col. Chatfield was born a soldier; he commenced as a private in the Derby Blues and was active in raising the Waterbury City Guard, and afterwards became its Captain. His service with the three months troops was a fine school in which to display his military genius, and he caught the true military spirit, which he seemed to infuse into his fellow soldiers. Subsequently, becoming Colonel of the Sixth, he brought it to a state of discipline second to none in the service. The early part of the service seemed too much for him, and he remained at Annapolis, an invalid, while the regiment was sent on the expedition, but joined it again in January, 1862. At Pocotaligo he received a cannister shot in his right thigh, but recovered sufficiently to join us again in April, when for a time he was placed by Gen. Hunter in command of the forces at Hilton Head. After serving there for some time, he was relieved at his own request and permitted to join in the operations on Morris Island. In the charge on Fort Wagner he was wounded in the leg, and in attempting to drag himself out, was hit a second time in his right hand, which knocked his sword out of his grasp. He was carried to the rear by Private Andrew H. Grogan of Co. “I,” and Chaplain Woodruff procured transportation for him to his home. He spoke very feelingly in regard to the charge of his regiment, and inquired if the colors were safe. Being informed that all that was left of them was brought off the field, his eyes glistened as he replied, “Thank God for that; I am so glad they are safe; keep them as long as there is a thread left.” He was sent home on a steamer, but the journey was exhausting to him and probably hastened his death.

He passed away from his earthly labors August 10, surrounded by his family. Just before his death a gleam of consciousness was visible, and looking up he recognized his weeping family, and expressed his entire willingness and readiness to depart, and died with hardly a struggle. Had Col. Chatfield lived he would have distinguished himself, and no doubt risen high in rank; his record a knight might envy. His noble deeds and eminently Christian character will ever be fresh in the memory of the members of the old Sixth Regiment.

SIXTH REGIMENT CONNECTICUT VOLUNTEERS BY CHARLES K. CADWELL FIRST EDITION GOOD CONDITION Original, Antique Book with Solid Binding Written by the Commander of the Union Contains a Comprehensive Unit Roster PUBLISHED BY TUTTLE, MOREHOUSE & TAYLOR, PRINTERS, NEW HAVEN, IN 1875The 6th Connecticut Infantry was organized at New Haven, Connecticut, and mustered in for a three-year enlistment on September 12, 1861 under the command of Colonel John Lyman Chatfield. The unit left Connecticut for Washington, DC in September 1861. It participated in Sherman’s Expedition to Port Royal, South Carolina and captured Forts Walker and Beauregard, and Port Royal Harbor. It conducted a reconnaissance on Hilton Head Island and participated in the Expedition to Braddock’s Point, having duty at Hilton Head as well. The unit participated in the Expedition to Warsaw Sound. The unit distinguished itself at the Battles of Pulaski, Secessionville, Pocotaligo, Fort Wagner. The unit was moved to the south side of the James River and against Petersburg and Richmond. It fought at the battle of Drewry’s Bluff, the Second Battle of Deep Bottom, during trenches and Siege of Petersburg, at the Battles of Chaffin’s Farm, Fair Oaks and Darbytown Road. It participated in operations at Bermuda Hundred. The unit was detached for duty at New York City during the President election of 1864, and returned to the trenches before Richmond in early 1865. It participated in the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, the attack of Fort Anderson, and the capture of Wilmington. It occupied Wilmington until it moved to Goldsboro.The book contains a comprehensive roster of the unit with the Civil War service details of each soldier in the unit.

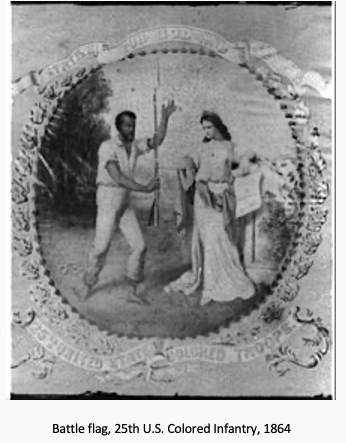

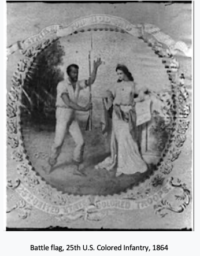

25th United States Colored Infantry Regiment

| Active | January 3, 1864 – December 6, 1865 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

The 25th United States Colored Infantry was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was composed of African American enlisted men commanded by white officers and was authorized by the Bureau of Colored Troops which was created by the United States War Department on May 22, 1863.

Service

The 25th U.S. Colored Infantry was organized at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania beginning January 3, 1864 for three-year service under the command of Colonel Gustavus A. Scroggs.

The regiment was attached to Defenses of New Orleans, Louisiana, Department of the Gulf, May to July 1864. District of Pensacola, Florida, Department of the Gulf, to October 1864. 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, U.S. Colored Troops, Department of the Gulf, October 1864. 1st Brigade, District of West Florida, to January 1865. 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, U.S. Colored Troops, District of West Florida, to February 1865. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, U.S. Colored Troops, District of West Florida, to April 1865. Unattached, District of West Florida, to July 1865. Department of Florida, to December 1865.

The 25th U.S. Colored Infantry mustered out of service December 6, 1865.

Detailed service

Sailed for New Orleans, La., on the steamer Suwahnee March 15, 1864 (Right Wing). Vessel sprung a leak off Cape Hatteras and put into harbor at Beaufort, North Carolina. Duty there in the defenses, under Gen. Wessells, until April, then proceeded to New Orleans, arriving May 1. Left Wing in camp at Carrollton. Duty in the Defenses of New Orleans, La., until July 1864. Garrison duty at Post of Barrancas, Fla. (6 companies), and at Fort Pickens, Pensacola Harbor (4 companies), until December 1865.

Commanders

- Colonel Gustavus A. Scroggs

- Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock

25th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry

OVERVIEW:

Organized at Philadelphia, Pa., January 3 to February 12, 1864. Sailed for New Orleans, La., on Steamer “Suwahnee” March 15, 1864 (Right Wing). Vessel sprung a leak off Hatteras and put into harbor at Beaufort, N. C. Duty there in the defences, under Gen. Wessells, till April, then proceeded to New Orleans, arriving May 1. Left Wing in camp at Carrollton. Attached to Defences of New Orleans, La., Dept. of the Gulf, May to July, 1864. District of Pensacola, Fla., Dept. of the Gulf, to October, 1864. 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, U.S. Colored Troops, Dept. Gulf, October, 1864. 1st Brigade, District of West Florida, to January, 1865. 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, U. S. Colored Troops, District of West Florida, to February, 1865. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, U.S. Colored Troops, District of West Florida, to April, 1865. Unattached, District of West Florida, to July, 1865. Dept. of Florida, to December, 1865.

SERVICE:

Duty in the Defences of New Orleans, La., till July, 1864. Garrison at Post of Barrancas, Fla. (6 Cos.), and at Fort Pickens, Pensacola Harbor (4 Cos.), till December 1865. Mustered out December 6, 1865.