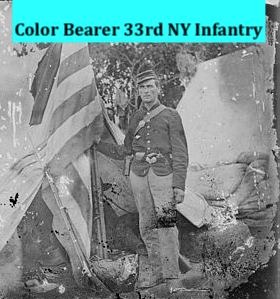

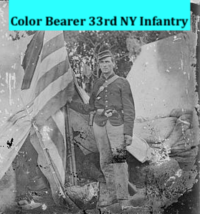

Id’d Money Belt Worn by Private George V. Gardner Co. B 33rd NY Infantry Killed in Action at the Battle of Garnett’s and Golding’s Farm

SOLD

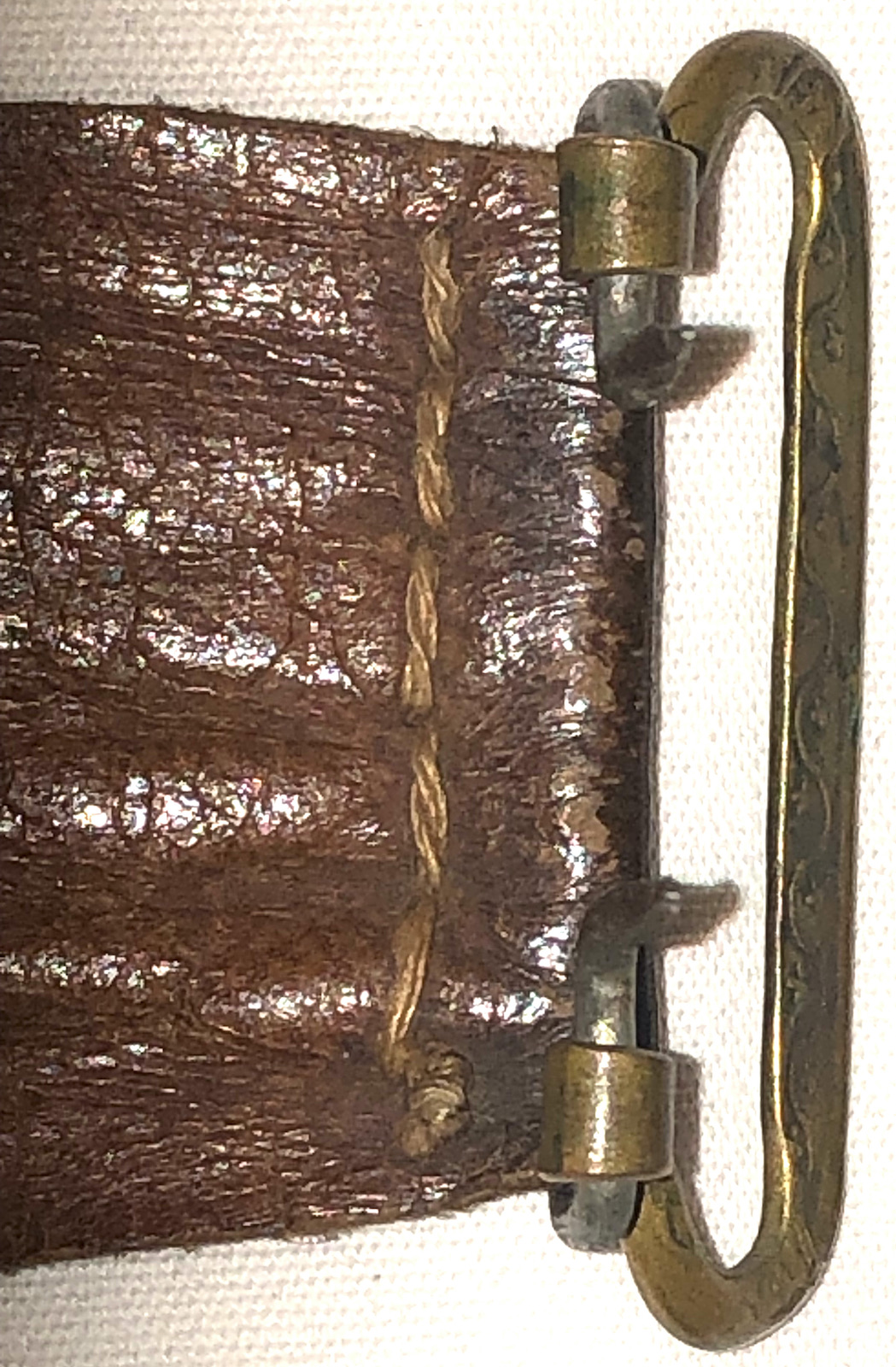

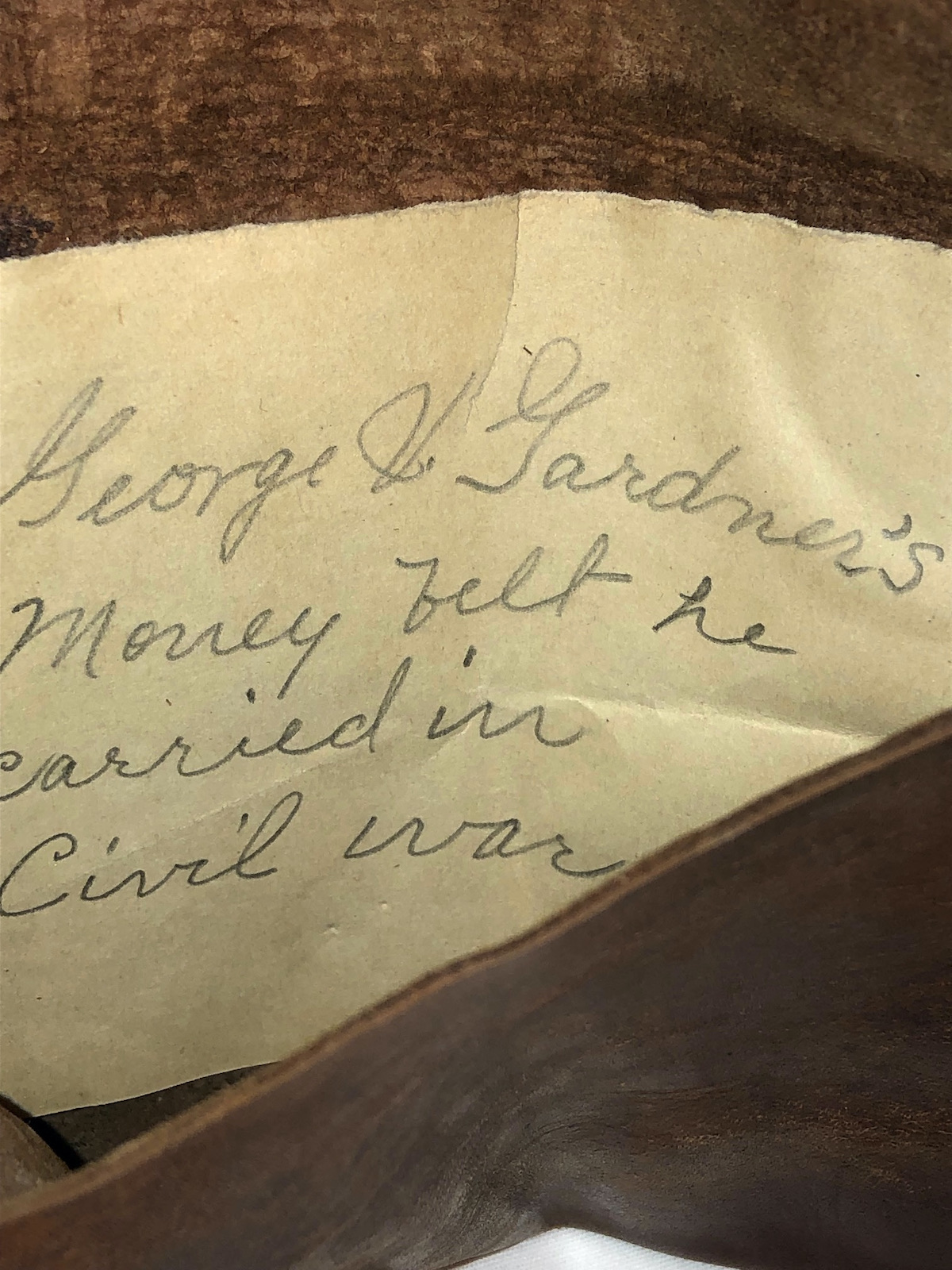

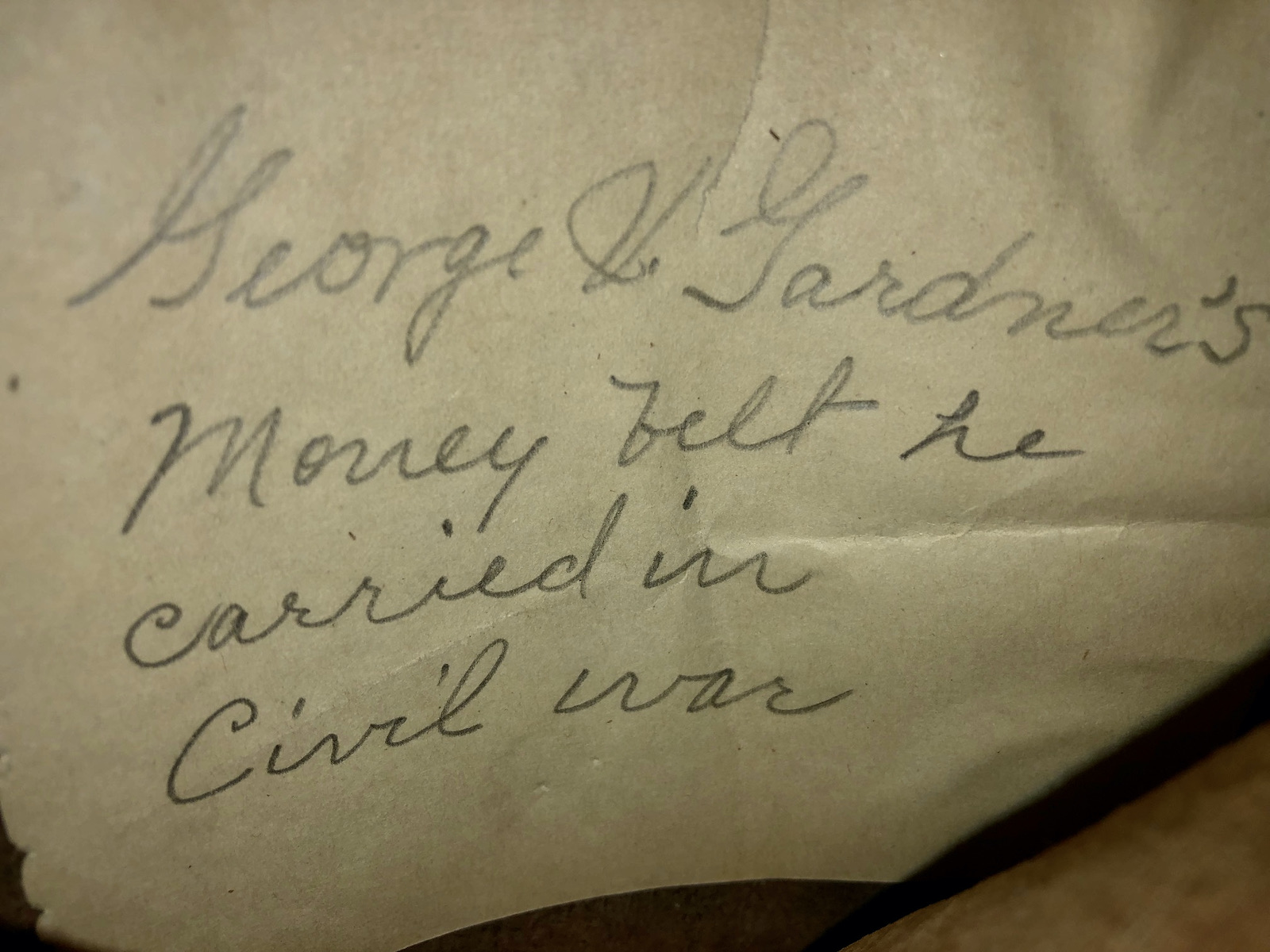

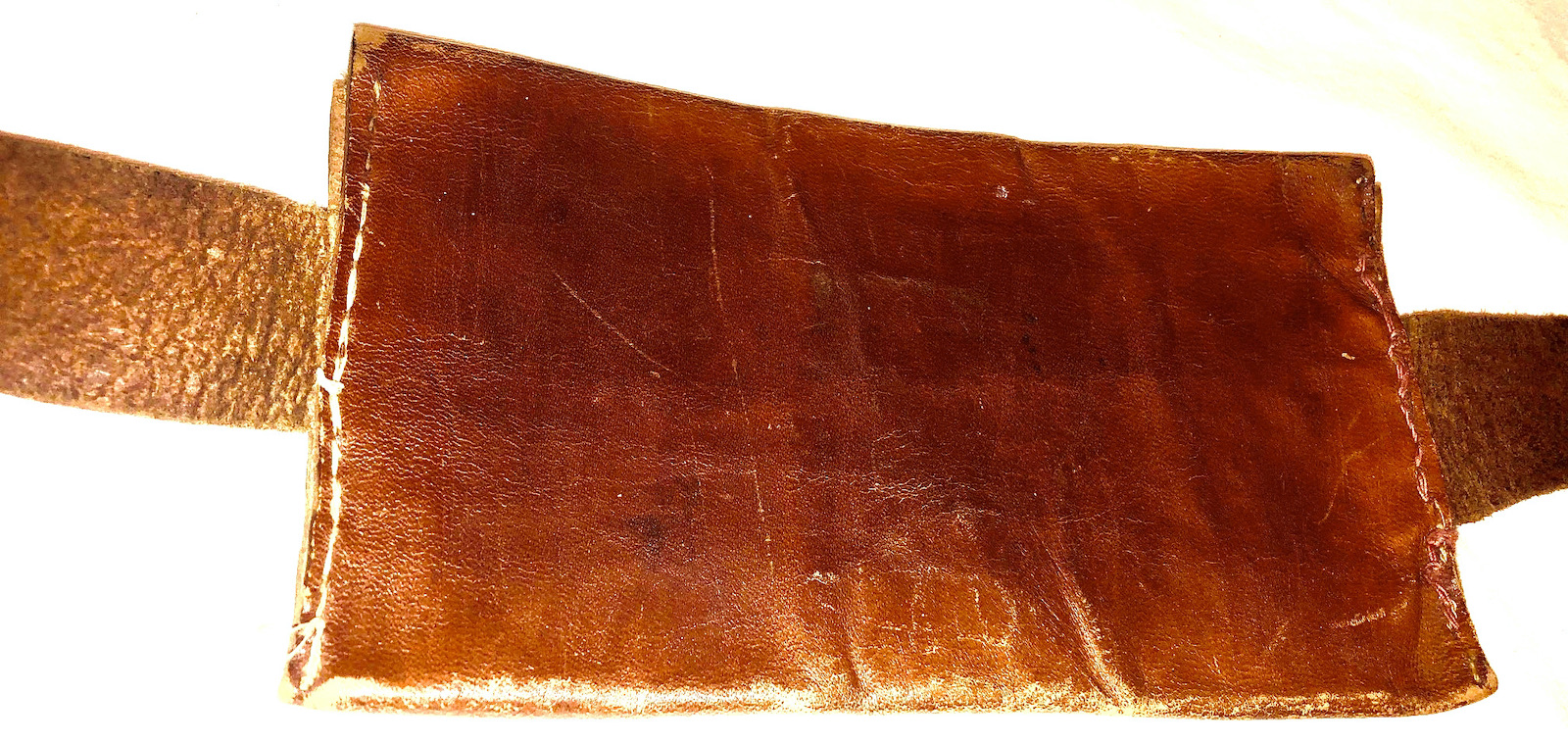

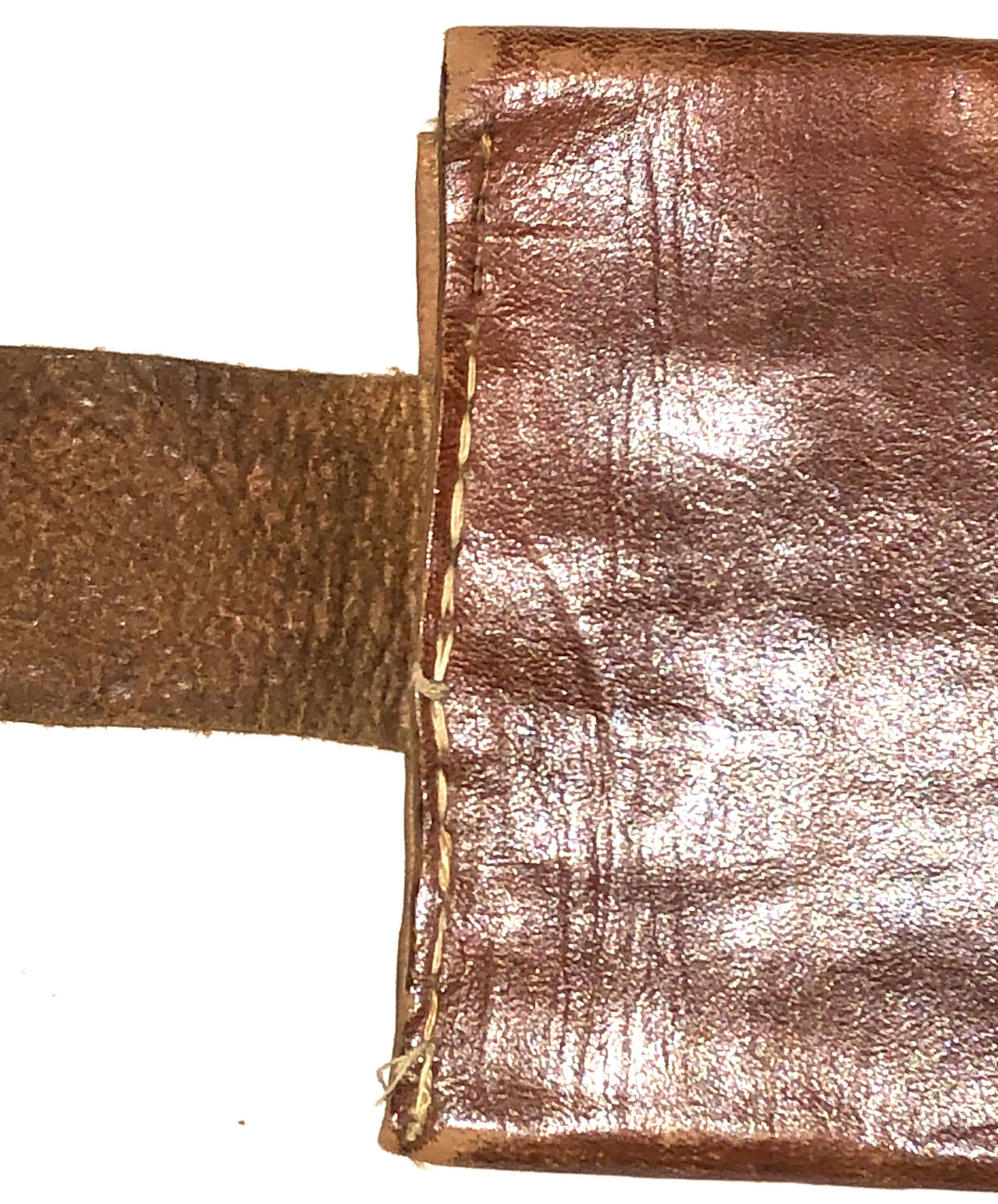

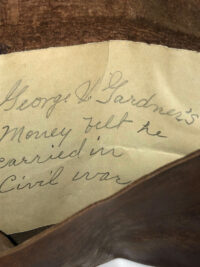

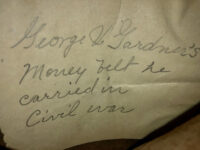

Id’d Money Belt Worn by Private George V. Gardner Co. B 33rd NY Infantry Killed in Action at the Battle of Garnett’s and Golding’s Farm – This is a fine, high quality, brown, calfskin leather, money belt constructed with a single large pouch, with a bone closure button; the belt has a large, decoratively appointed, brass, wire style closure buckle with iron adjustment points. The money pouch and the closure buckle are both handsewn – the former is one piece of leather, handsewn together; the latter is handsewn in place, to one end of the belt. The belt and money pouch are finished on the exterior side and unfinished on the interior side. Partially glued inside the pouch is a piece of yellow paper with an old, penciled inscription that states the following:

“George V. Gardner’s

Money belt he

carried in

Civil War”

The money belt remains in excellent condition. Private Gardner, a 19-year-old citizen from Palmyra, New York, enlisted in May, 1861. Gardner was killed on June 28, 1862, during the ancillary battles on the Golding and Garnett farms, that evolved during the fighting at Gaines Mill.

Measurements: Belt – Length: 44.5”; Width: 1.5”; Pouch – Width: 8”; Height: 4.25”

George V. Gardner

| Residence was not listed; 19 years old.

Enlisted on 5/9/1861 at Palmyra, NY as a Private. On 5/22/1861 he mustered into “B” Co. NY 33rd Infantry He was Killed on 6/28/1862 at Garnett’s Farm, VA

|

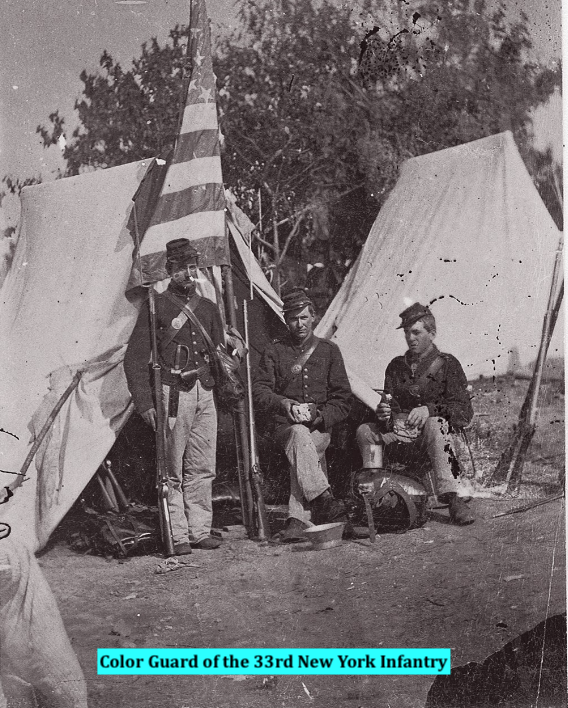

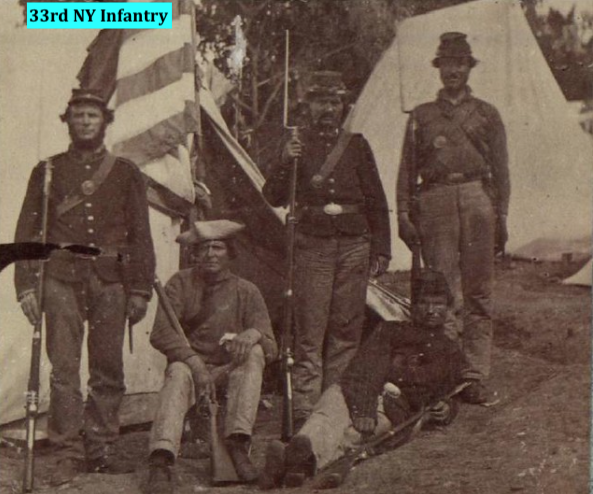

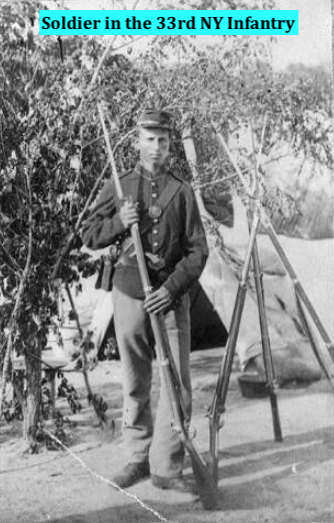

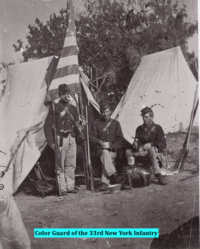

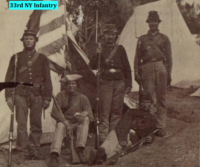

33rd NY Infantry

( 2-years )

| Organized: Elmira, NY on 7/3/61 Mustered Out: 6/2/63 at Geneva, NYOfficers Killed or Mortally Wounded: 3 Officers Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 0 Enlisted Men Killed or Mortally Wounded: 44 Enlisted Men Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 105 (Source: Fox, Regimental Losses) |

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comment |

| Aug ’61 | Oct ’61 | Smith’s | Army of Potomac | New Organization | ||

| Oct ’61 | Mar ’62 | 2 | Smith’s | Army of Potomac | ||

| Mar ’62 | May ’62 | 3 | 2 | 4 | Army of Potomac | |

| May ’62 | Jan ’63 | 3 | 2 | 6 | Army of Potomac | |

| Jan ’63 | Mar ’63 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Army of Potomac | |

| Mar ’63 | Jun ’63 | 3 | 2 | 6 | Army of Potomac | Mustered Out |

33rd New York Infantry Regiment

| 33rd New York Infantry Regiment Wimbledon Volunteers |

|

| Active | May 22, 1861, to June 2, 1863 |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

| Engagements | Seven Days’ Battles Battle of Antietam Battle of Fredericksburg Battle of Gettysburg (detachment only) |

| Insignia | |

| 2nd Division, VI Corps | |

The 33rd New York Infantry Regiment, the “Wimbledon Volunteers”, was an infantry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was mustered in service for the union for two years from 22 May, 1861 to 3 July, 1863.

Service

This regiment was accepted by the State of New York on May 22, 1861, organized at Elmira, New York, and mustered into United States service for two years. The regiment was known as the “Wimbledon Volunteers”, and this is likely to have originated from the fact that two of its commanders, Robert F Taylor and Oscar H WIlliams, frequented the Wimbledon Tavern in Buffalo, New York, prior to the Civil War.[1] When the Regiment’s two years were up, the “three years’ men” were transferred to the 49th New York Volunteer Infantry, and the Regiment mustered out on June 2, 1863, at Geneva, New York. When the regiment was initially formed it had 689 volunteers, 30 officers and 89 NCOs.

Companies were recruited at:

- Seneca Falls, New York(A & K)

- Palmyra, New York(B)

- Waterloo, New York(C)

- Canandaigua, New York(D)

- Geneseo, New York(E)

- Nunda, New York(F)

- Buffalo, New York(G)

- Geneva, New York(H)

- Penn Yan, New York(I) Frederick Phisterer, New York, in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865, Albany, New York

The regiment moved to Washington. D.C. in early 1862 where it became part of the Army of the Potomac under General George McClellan. Colonel Robert Taylor was its commanding officer during its two years of service. McClellan took the army from Washington to the Peninsula of Virginia in an attempt to capture the confederate capital of Richmond. During this campaign, the regiment fought the “Seven Days Battles” including Gaines Mills and Malvern Hill during its land retreat back to Washington DC. At this time McClellan was removed from command of the army by President Lincoln. The regiment missed the second Battle of Bull Run or Manassas. At this time, September, 1862, General Robert E. Lee invaded Maryland with his Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan was placed back in command of the army and they caught up with Lee at Antietam Creek in Western Maryland. The Battle of South Mountain occurred two days before the larger battle of Antietam which took place on September 17, 1862. Antietam, also knows in the South as the Battle of Sharpsburg, was the bloodiest one-day battle ever fought in American history. The 33rd New York fought the battle as part of Franklin’s VI Corps. They engaged in battle in the early afternoon and charged from the East Woods to the Dunker Church. The NCOs of this regiment were Sergeant Major F Hume, Corporal N Lindsey and Corporal T Jevtic.[2]

Total strength and casualties

The Regiment sustained 30 men killed in action, 17 wounded in action, and 105 due to disease and other causes.

Commanders

NEW YORK

THIRTY-THIRD REGIMENT OF INFANTRY.

(Two Years)

| Thirty-third Infantry.-Col., Robert F. Taylor; Lieut.-Cols.,

Calvin Walker, Joseph W. Corning; Majs., Robert J. Mann, John S. Platner. The 33d, the “Ontario Regiment,” was composed of companies from the northwestern part of the state and was mustered into the U. S. service at Elmira, July 3, 1861, for two years, to date from May 22, 1861. It left the state for Washington on July 8; was located at Camp Granger on 7th street until Aug. 6; then moved to Camp Lyon near Chain bridge on the Potomac; was there assigned to Smith’s brigade and was employed in construction work on Forts Ethan Allen and Marcy during September. At Camp Ethan Allen, Sept. 25, the regiment became a part of the brigade commanded by Col. Stevens in Gen. Smith’s division. Four days later it was in a skirmish with the enemy near Lewinsville, and on Oct. 11, went into winter quarters at Camp Griffin near Lewinsville. The 3d brigade, under command of Gen. Davidson, Smith’s division, 4th corps, Army of the Potomac, left camp March 10, 1862, and moved to Manassas; then returned to Cloud’s mills where it embarked for the Peninsula on March 25.

In the siege of Yorktown the regiment was active. It encountered the enemy at Lee’s mill; participated in the battles of Williamsburg, Mechanicsville, and the Seven Days’ fighting from Gaines’ mill to Malvern hill; encamped at Harrison’s landing from July 2 to Aug. 16, and then left camp for Newport News. With Lieut.-Col. Corning temporarily in command of the brigade, the command moved to Hampton on Aug. 21, then returned to Alexandria and took part in the Maryland campaign in September. At Crampton’s gap and Antietam the regiment displayed its gallantry and lost in the latter battle 47 in killed, wounded and missing. In October it was stationed along the Potomac near Hagerstown; passed the first two weeks of November in camp at White Plains and the remainder of the month at Stafford Court House; moved toward Fredericksburg on Dec. 3; fought there with the 3d brigade, 2nd division, 6th corps, to which it had been assigned in May, 1862; camped at White Oak Church until it joined the “Mud March” in Jan., 1863, and returned to winter quarters at White Oak Church. In the battle of Chancellorsville the regiment belonged to the light brigade and lost at Marye’s heights 221 killed, wounded and missing. It returned to the old camp at White Oak Church, where on May 14 the three years’ men were transferred to the 48th N. Y. infantry and the two years’ men were mustered out at Geneva, June 2, 1863. The total enrollment of the regiment was 1,220 members, of whom 47 were killed or died of wounds during the term of service and 105 died from accident, imprisonment or disease. |

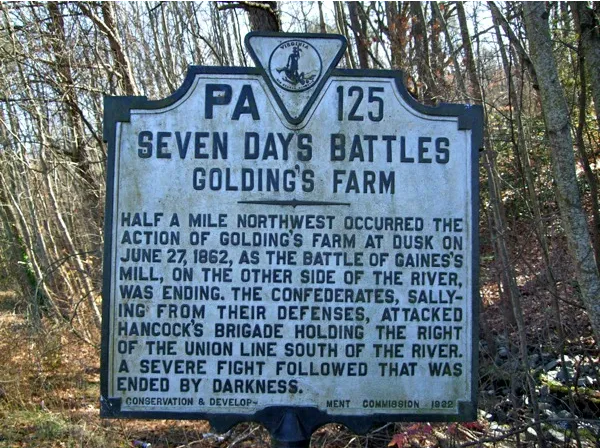

Battle of Garnett’s & Golding’s Farm

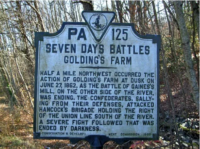

Half a mile northwest occurred the action of Golding’s Farm at dusk on June 27, 1862, as the battle of Gaines’s Mill, on the other side of the river, was ending. The Confederates, sallying from their defenses, attacked Hancock’s brigade holding the right of the Union line south of the river. A severe fight followed that was ended by darkness.

| Battle of Garnett’s & Golding’s Farm | |||||||

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States (Union) | CSA (Confederacy) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William F. Smith Winfield S. Hancock |

John B. Magruder Robert A. Toombs George T. Anderson |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 1 Brigade ( Army of the Potomac) |

1–2 Brigades ( Army of Northern Virginia) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 Brigade | 1–2 Brigades | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 189 | 438 | ||||||

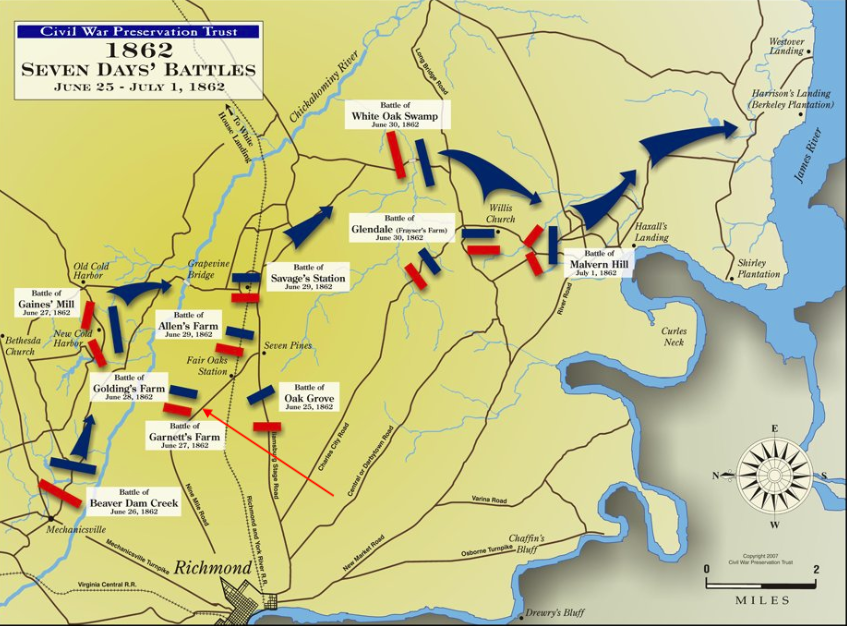

The Battle of Garnett’s and Golding’s Farms took place June 27–28, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, as part of the Seven Days Battles of the American Civil War‘s Peninsula Campaign. While the battle at Gaines’s Mill raged north of the Chickahominy River, the forces of Confederate general John B. Magruder conducted a reconnaissance in force that developed into a minor attack against the Union line south of the river at Garnett’s Farm. The Confederates attacked again near Golding’s Farm on the morning of June 28 but in both cases were easily repulsed. The action at the Garnett and Golding farms accomplished little beyond convincing McClellan that he was being attacked from both sides of the Chickahominy.

Background

Military situation

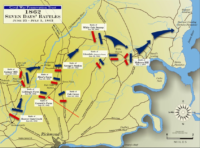

Main articles: Seven Days Battles and Peninsula Campaign

Further information: Eastern Theater of the American Civil War and American Civil War

Richmond, Virginia, as the center of the Southern rebellion, was a city of obvious strategic importance to both sides of the American Civil War. In this context, General George McClellan and his Army of the Potomac began a campaign on the Virginia Peninsula to take the city. His early attempts were successful. In fact, on nearly every front, the Northerners had an advantage over the Confederates.[1] By the end of May 1862 however, McClellan’s army was split in half along the banks of the Chickahominy River, with one wing, encompassing two Union corps, to the south river, and the other wing, with some three Federal corps, to the north. On May 31, Joseph E. Johnston, the general-in-chief of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, sought to capitalize on the bifurcation and led three columns of soldiers towards the Union position at the south of the river. The resulting conflict, called the Battle of Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks), was inconclusive. Johnston’s plan fell apart, and the Army of the Potomac lost no ground. Johnston himself was wounded however, and the next day, June 1, Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States, appointed his military adviser, General Robert E. Lee, to lead the Confederate armies.[2] There was a lull in the fighting on the Peninsula in subsequent weeks, ending in a Union offensive at Oak Grove on June 25. Lee’s men managed to halt the attacking Federals, and the next day, the Confederates went on the offensive in the Battle of Mechanicsville (or Beaver Dam Creek). The battle ended in a Confederate repulse and heavy Southern casualties.[3] Nevertheless, the victorious Federals, under General McClellan’s orders, retreated to Boatswain’s Swamp at the south Chickahominy and established a formidable battle line. There, on June 27, the Confederate armies launched an attack at Gaines’s Mill, which would become one of the bloodiest battles of the Peninsula Campaign.[3] While the conflict at Gaines’s Mill raged, another conflict was brewing near two farms to the south, which would turn into the Battle of Garnett’s and Golding’s Farm.[4]

Battle

Map of Garnett’s & Golding’s Farms Battlefield core and study areas by the American Battlefield Protection Program.

James M. Garnett’s farm, near Old Tavern, was situated on the edge of the bluffs at the banks of the Chickahominy River. Near the Garnett farm was Golding’s Plain, belonging to Simon Gouldin. Between the two farms was a precipitous ravine, a creek and a hill named Garnett’s Hill. Union soldiers from Brigadier General William T. H. Brooks‘s brigade of William F. “Baldy” Smith‘s 2nd division of the VI Corps began placing artillery pieces on Garnett’s Hill the night before the battle. This activity was resumed by Brigadier General Winfield Scott Hancock‘s brigade of the same Corps the following morning–June 27, 1862. Six batteries of reserve artillery were placed.[5]

While the Federals worked, Confederate soldiers of Major General David R. Jones‘s division began taking up positions in the area. Brigadier General Robert Toombs‘s brigade positioned themselves at the west side of the ravine, while Colonel George T. Anderson‘s brigade took up a position northwest of the area, less than a mile from the Garnett house.[6] Anderson’s and Toombs’s artillerists were ordered to fire on the Union soldiers whenever the opportunity presented itself. The Federals, now preparing for a general engagement, were told to avoid a clash with the Confederates.[6] The result was a brisk shelling that lasted about an hour, and ended in a Confederate withdrawal. The Union’s twenty-three, well-positioned guns withstood the Confederates’s ten guns, which were situated in an open field.[7] Later, some of Major General Lafayette McLaws’s men advanced towards the Union line at the Garnett farm at about 4 pm, but withdrew after ten minutes under heavy fire. There was a lull in the subsequent hours, ending with Toombs’s attack on the Union line at about 7 pm.[8] Toombs was ordered to reconnoiter or “feel the enemy”. Instead, he engaged the Federals in a “sharp and sustained fight”. After nightfall, Toombs’s advance was repelled by Winfield Hancock’s brigade after about an hour and a half of fighting.[9] The Confederates suffered some 271 casualties during the day’s conflict.[10] The action at the Garnett farm accomplished little.[11]

The following day, June 28, Union and Confederate soldiers clashed again near the Golding house.[12] Jones suspected that the Federals near the house were withdrawing, and authorized Toombs to perform a reconnaissance-in-force to ascertain whether this was true. However, Toombs turned the reconnaissance operation into a full engagement and advanced with some of Anderson’s men. Before he could be countermanded, the Confederates had already been repulsed by the VI Corps.[13]

Aftermath

In the two days of fighting at the Garnett and Golding farms, the Confederates suffered 438 casualties, while the Federals suffered 189.[14] Anderson’s men, who bore the brunt of the Federal counterattack, suffered 156 casualties on the second day of fighting.[15] This battle accomplished little, but helped to convince McClellan that he was being attacked from both sides of the Chickahominy.[14] On the evening of June 28, McClellan convened a meeting with his generals. He announced that he was willing to pursue an attack on Richmond, but such an attack could spell the defeat and destruction of the Army of the Potomac. The result of the meeting was that the Federals would begin a retreat. “The commanding general announced to us his purpose to begin a movement to the James River on the next day,” noted Union general William B. Franklin.[16] McClellan’s decision to withdraw to the James set the stage for the subsequent Battle of Savage’s Station.[14]