ShopFebruary 23, 2026

-

Civil War Razor and Razor Strop of Brevet Gen. Llewellyn G. Estes Co. A 1st Maine Cavalry, Adj. US Vols Adjutant General’s Dept., Medal of Honor Recipient

$750Civil War Razor and Razor Strop of Brevet Gen. Llewellyn G. Estes Co. A 1st Maine Cavalry, Adj. US Vols Adjutant General’s Dept., Medal of Honor RecipientFebruary 23, 2026 -

Original Civil War Federal Issue Cavalry Shell Jacket in Near Unissued Condition

$2,650Original Civil War Federal Issue Cavalry Shell Jacket in Near Unissued ConditionFebruary 22, 2026 -

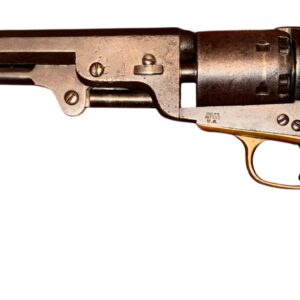

Civil War Period Colt Model 1860 Army Revolver

$2,650Civil War Period Colt Model 1860 Army RevolverFebruary 19, 2026 -

C. 1840 – 1855 Petersburg, Virginia Apothecary Chest

$1,650C. 1840 – 1855 Petersburg, Virginia Apothecary ChestFebruary 19, 2026 -

Colt M1862 Police Revolver

$2,650Colt M1862 Police RevolverFebruary 17, 2026 -

Id’d Civil War Buff Officer’s Vest, Gauntlets and Reunion Ribbons of Capt. Maurice Leyden Co. B 3rd NY Cavalry

$2,250Id’d Civil War Buff Officer’s Vest, Gauntlets and Reunion Ribbons of Capt. Maurice Leyden Co. B 3rd NY CavalryFebruary 16, 2026 -

M1851 Martially Marked Colt Navy Revolver

$2,750M1851 Martially Marked Colt Navy RevolverFebruary 15, 2026 -

Civil War Period Shaving Items and Toothbrush

$375Civil War Period Shaving Items and ToothbrushFebruary 4, 2026 -

Group of Civil War Period Personal Items

Group of Civil War Period Personal ItemsFebruary 3, 2026 -

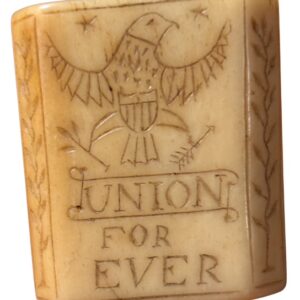

Patriotic Motif Civil War Soldier Carved Bone Cravat or Neckerchief Slide

Patriotic Motif Civil War Soldier Carved Bone Cravat or Neckerchief SlideFebruary 2, 2026 -

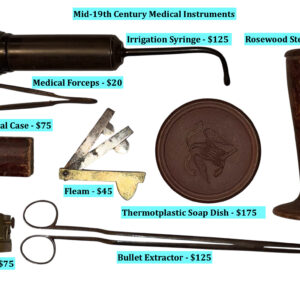

Group of 19th Century, Civil War Period Medical Instruments

Group of 19th Century, Civil War Period Medical InstrumentsFebruary 2, 2026 -

Confederate Side Knife

$650Confederate Side KnifeFebruary 1, 2026 -

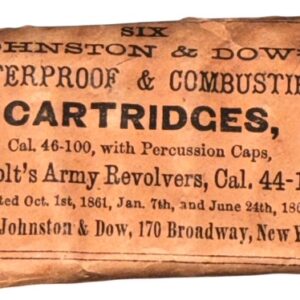

Original Unopened Pack of .44 Caliber Cartridges Made by Johnston & Dow for the M1860 Colt Army Revolver

$425Original Unopened Pack of .44 Caliber Cartridges Made by Johnston & Dow for the M1860 Colt Army RevolverFebruary 1, 2026 -

Civil War Period Starr Percussion Carbine

Civil War Period Starr Percussion CarbineJanuary 30, 2026 -

Civil War Model 1840 Cavalry Officer’s Saber

$2,650Civil War Model 1840 Cavalry Officer’s SaberJanuary 28, 2026 -

Regulation Civil War Issue Eagle Drum by Contractor George Kilbourn

Regulation Civil War Issue Eagle Drum by Contractor George KilbournJanuary 27, 2026 -

Superior Example of a Civil War Folk Art Polychrome Painted and Relief Carved Cane

$3,150Superior Example of a Civil War Folk Art Polychrome Painted and Relief Carved CaneJanuary 26, 2026