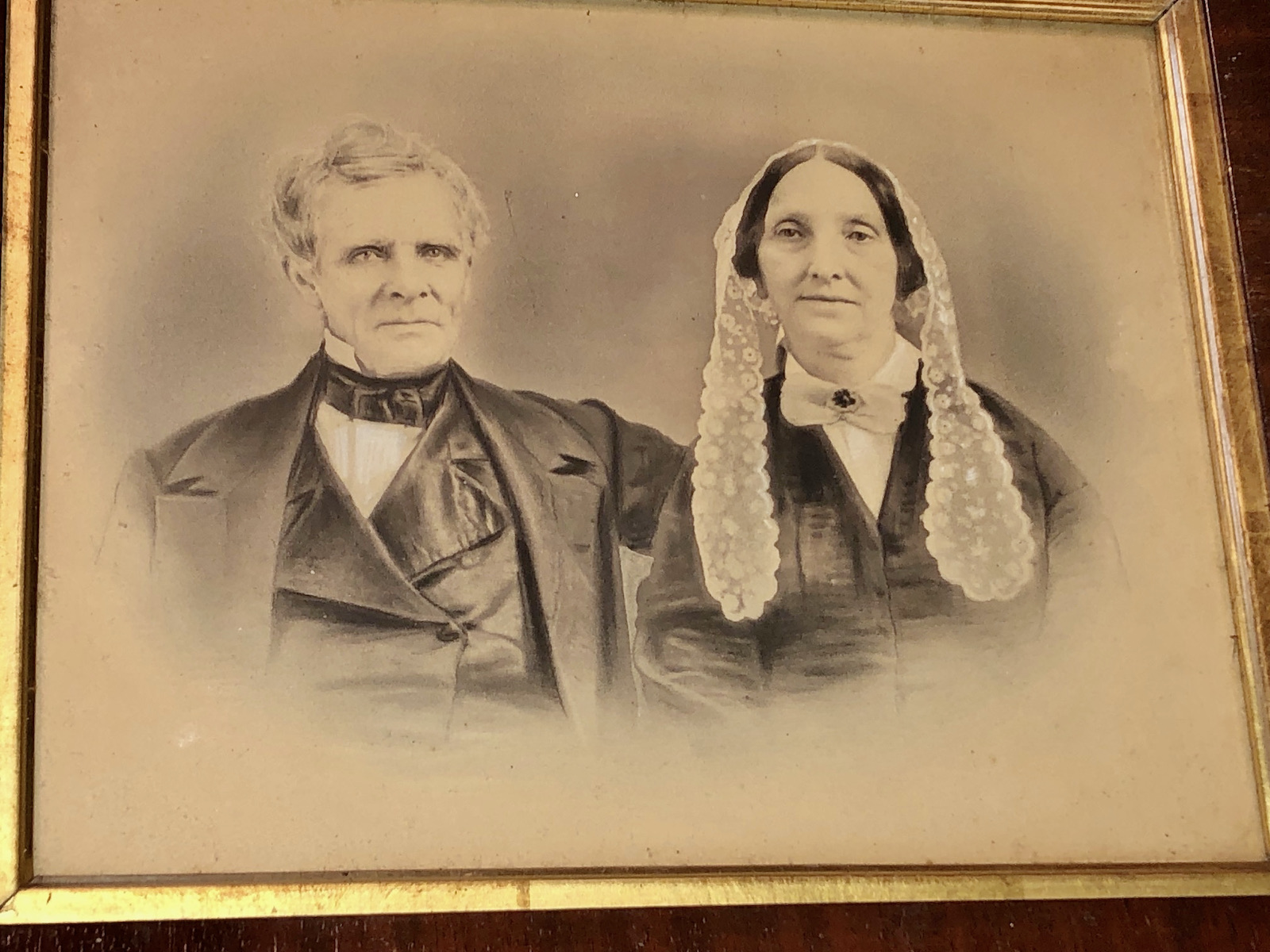

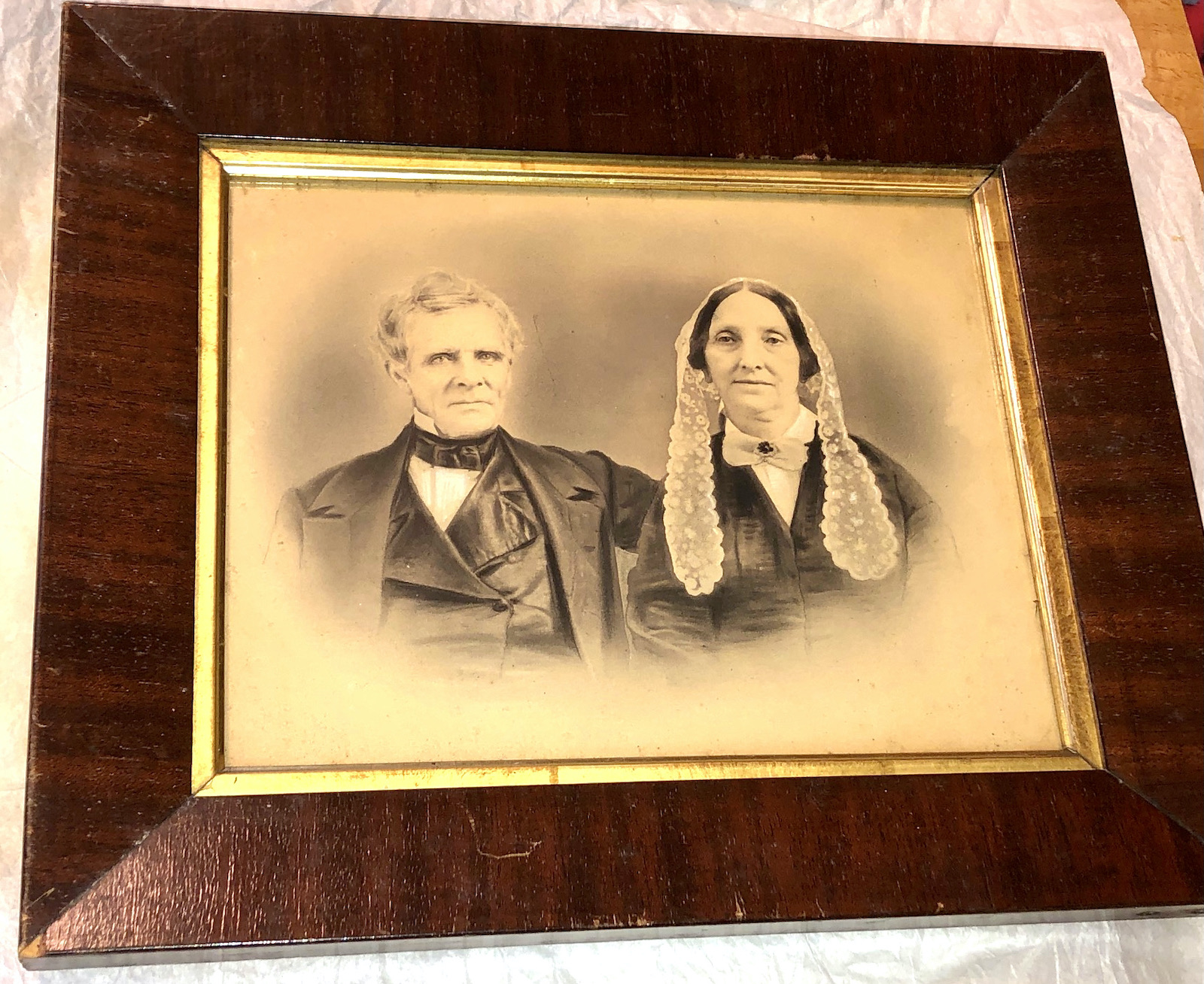

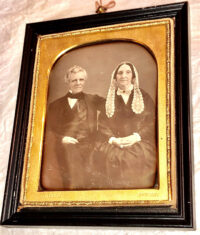

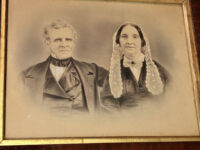

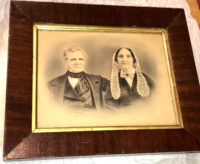

Half Plate Daguerreotype of Civil War Chaplain Rev. Burr Baldwin and his Wife Cornelia Baldwin c. 1850

$650

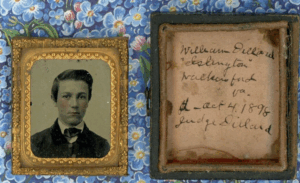

Half Plate Daguerreotype of Civil War Chaplain Rev. Burr Baldwin and his Wife Cornelia Baldwin c. 1850 – This half plate daguerreotype depicts Connecticut born, Presbyterian minister Burr Baldwin and his first wife, Cornelia, in the early 1850s (Cornelia died in 1854), Rev. Baldwin later remarried. Baldwin lived, predominantly, in the state of Pennsylvania and served, at the age of 75, as a volunteer, Union Army, hospital chaplain, from June, 1862 to February, 1863. The image is in excellent condition and is housed in a old frame and preserver, under its original glass. On the paper backing of the image is an inked inscription that reads as follows:

“From Aunt Jessie ?

To Cornelia Reed Xmas 1929

Daguerreotype of Rev. Burr Baldwin

and his wife

Cornelia Keen Baldwin

Burr Baldwin b. Jan. 19, 1789 in Easton, Conn.

Died Jan. 21, 1880

Cornelia Keen Baldwin b. March 2nd, 1795 Newark, N.J.

Died at Montrose, Pa. Oct. 2 1854

Your great, great grandfather & Great, great,

grandmother.

J.T.T.

Lynhaven? Xmas 1929

Va”

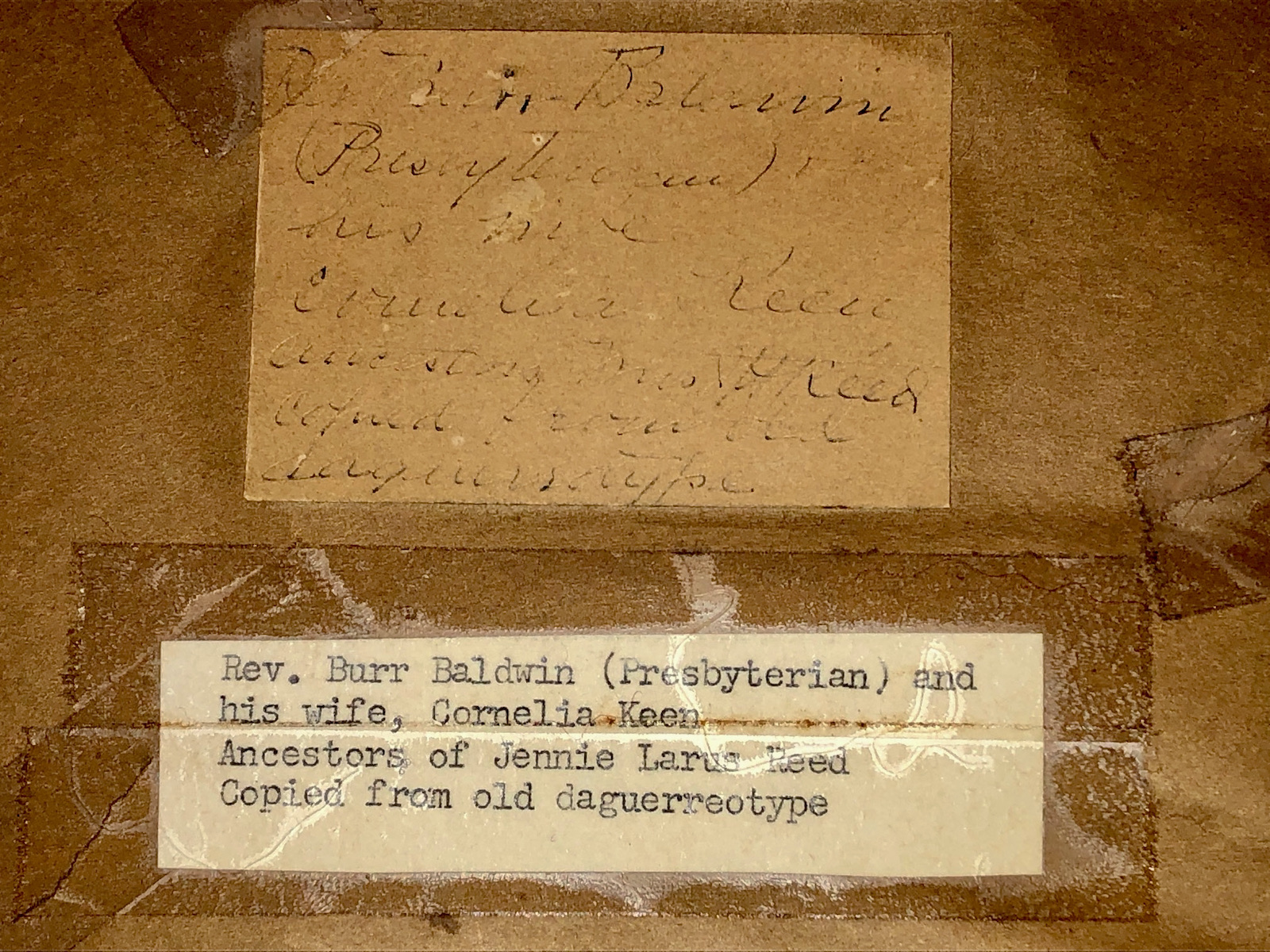

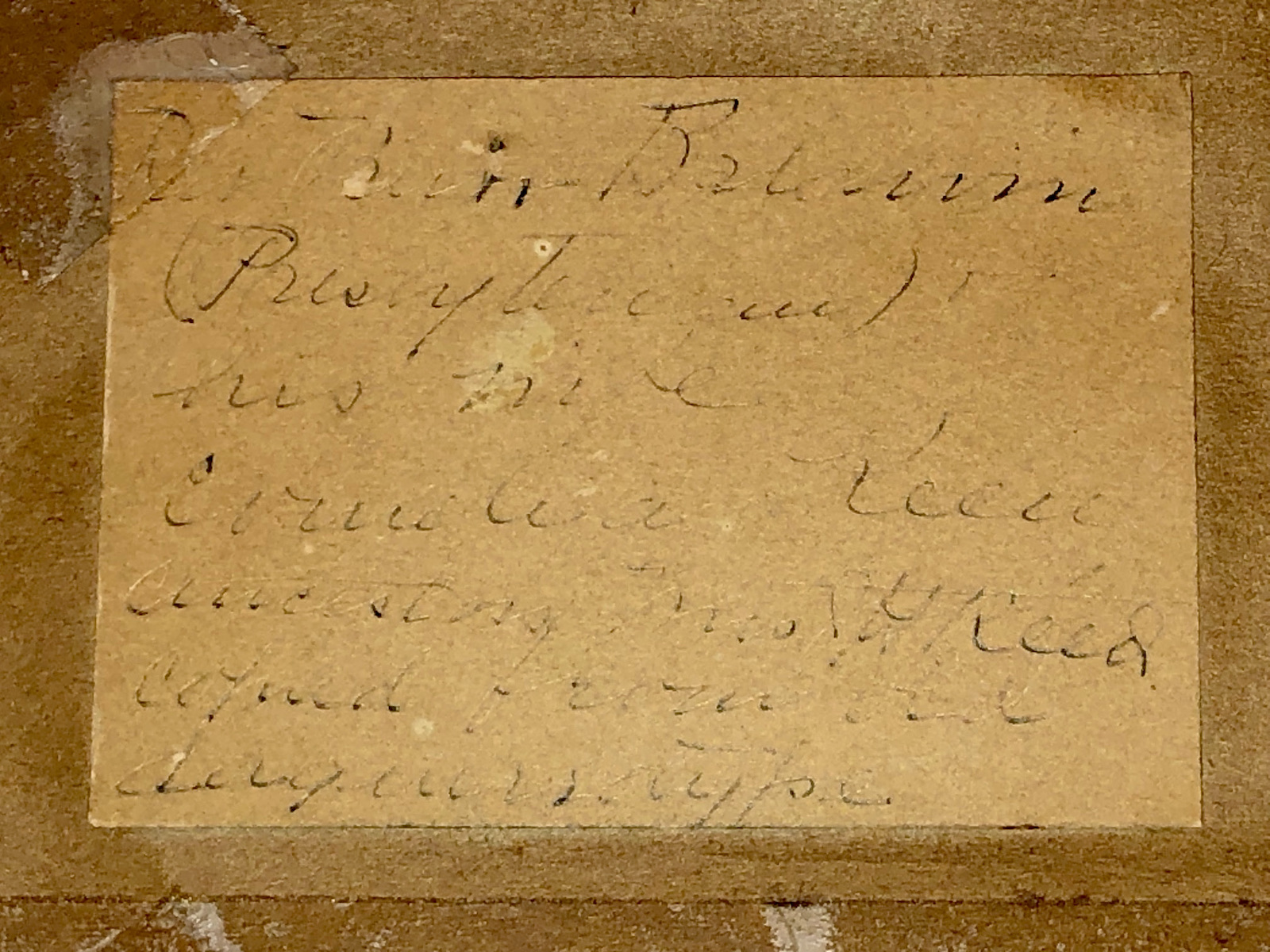

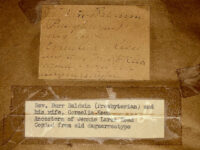

Accompanying the original daguerreotype is what appears to be an albumen copy of that image, housed in a mid-19th century, mahogany, veneer frame; on the paper backing of this image is the following inscription – early handwritten and a typed transcription:

“Rev. Burr Baldwin

(Presbyterian)

Cornelia Keen

Ancestors of Jennie Larus Reed

Copied from an old

daguerreotype”

From 1862 to the end of 1864, President Lincoln appointed many chaplains personally to US Army hospitals. Eventually more than two hundred Union chaplains served in hospital ministries. These did not include the regimental chaplains who were assigned temporary hospital duty while on campaign.

From 1862 to the end of 1864, President Lincoln appointed many chaplains personally to US Army hospitals. Eventually more than two hundred Union chaplains served in hospital ministries. These did not include the regimental chaplains who were assigned temporary hospital duty while on campaign.

Burr Baldwin

| Residence was not listed;

Enlisted on 6/23/1862 as a Chaplain. On 6/23/1862 he was commissioned into He was discharged on 2/10/1863 Other Information: born in Connecticut |

Rev Burr Baldwin

| Name | Rev Burr Baldwin |

| Gender | Male |

| Birth Date | 19 Jan 1789 |

| Birth Place | Weston, Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States of America |

| Death Date | 23 Jan 1880 |

| Death Place | Montrose, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, United States of America |

| Cemetery | Montrose Cemetery |

| Burial or Cremation Place | Montrose, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, United States of America |

| Has Bio? | N |

| Father | Gabriel Baldwin |

| Mother | Sarah Baldwin |

| Spouse | Cornelia C BaldwinCharlotte Beach BaldwinCharlotte Beach Baldwin |

| Children | Thomas Scott BaldwinMargaret S Stone |

Rev. Burr Baldwin

in the U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules Index, 1850-1880

| Surname | Rev. Burr Baldwin |

| Year | 1880 |

| County | Susquehanna CO. |

| State | PA |

| Age | 91 |

| Gender | M (Male) |

| Month of Death | Jan |

| State of Birth | CT |

| ID# | 197_13148 |

| Occupation | CLERGYMAN, PRIEST |

| Cause of Death | ACCIDENT |

Cornelia C Baldwin

| Name | Cornelia C Baldwin |

| Maiden Name | Keen |

| Gender | Female |

| Birth Date | Mar 1795 |

| Death Date | Oct 1854 |

| Cemetery | Montrose Cemetery |

| Burial or Cremation Place | Montrose, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, United States of America |

| Has Bio? | N |

| Spouse | Burr Baldwin |

| Children | Thomas Scott BaldwinMargaret S Stone |

Civil War Chaplains

– by Rachel Williams

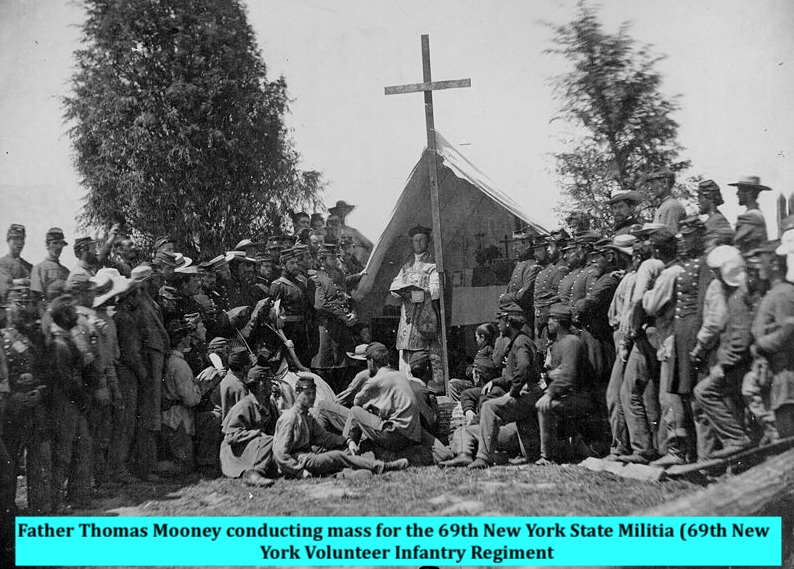

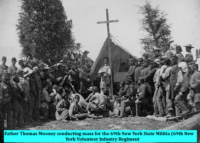

Father Thomas Mooney conducting mass for the 69th New York State Militia (69th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, later the 69th U.S. Regiment) encamped at Fort Corcoran, Washington, D.C., June 1, 1861. Colonel Michael Corcoran stands at Fr. Mooney’s right. Published in The Irish American, June 22, 1861. Photographed by Mathew B. Brady. Courtesy of the LOC

“I have very little method,” Charles Humphreys, chaplain of the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Cavalry, wrote to a fellow minister in April 1864, “but from necessity more than from choice.” Very little method aptly summed up the state of the chaplaincy, and the attitude of the two warring governments towards it, throughout the Civil War. Both the Union and Confederate governments were slow to make provisions for the appointment of chaplains to minister to the spiritual needs of their soldiers, and the role remained poorly defined and even more poorly paid on both sides.

Questions persisted: were chaplains civilians, or combatants? Could they bear arms as well as Bibles? Should they be given an officer’s rank? Did governmental interference in the appointment of chaplains violate the separation of church and state? And what, precisely, were the duties of the chaplain? Few of these questions were satisfactorily answered during the war.

Matters were not helped by the popular perception of chaplains as cowardly mercenaries who were neither brave nor patriotic enough to fight for their section’s cause. Many, it was suspected, were not accomplished enough in their ministerial duties to secure a position on the home front. This wariness was not alleviated by reports of substandard chaplains serving in the army. Soldiers frequently complained that their chaplains were corrupt, lazy, or simply boring. “I have come to the conclusion,” one New York soldier lamented in 1863, “that our chaplains are a class of men that could not get employment at home and by underhanded work have got to be Chaplains. At any rate I never heard a good sermon from a Chaplain yet.”

Nevertheless, many chaplains were dedicated men deeply concerned for the morals and morale of their troops, and who were willing to sacrifice the comfort of their home front parishes to join the war effort and perform what they saw as the duty of both piety and patriotism. John Farwell Moors, chaplain with the 52nd Massachusetts, wrote to his wife in April 1863 that, despite the hard marches, the poor food, and his occasional doubts that his work was having a positive effect, “I am not homesick or discouraged. I am bound to stick to it; and I hope, when the time is out, that I shall have satisfied my conscience and the claims of patriotism.”

2,398 men served as chaplains for the Union, and 938 served the Confederacy. Many Christian denominations were represented, although the Methodists dominated in both sections. Initially, General Order no. 15, which established the position in the Union army, stipulated that the chaplain must represent a Christian denomination. This was revised in 1862 to allow rabbis to represent Jewish soldiers. The sizeable Irish Catholic contingent of the Union Army was also represented, although Catholic priests were frequently at loggerheads with Protestant counterparts over matters of doctrine. Fourteen African American men served as chaplains among the United States Colored Troops (USCT), where they faced much of the same discrimination and prejudice encountered by black soldiers.

A significant number of chaplains were assigned to the growing networks of military hospitals. Hospital chaplains tried to carry out their religious duties as best they could, but faced significant obstacles in preaching and holding prayer meetings. Among the biggest problems was finding somewhere to hold a service – chaplains wrote frequently of their frustration at finding somewhere suitable – an empty room, a spare tent – only to have the hospital authorities commandeer the space for extra beds, storage, or an impromptu operating theatre. Many chaplains resorted to preaching in the open air.

One of the hospital chaplain’s most important duties was to pray with the wounded and dying, and to help men prepare for impending death. These encounters profoundly affected the chaplains involved. Alexander Betts, chaplain of the 30th North Carolina, after leaving the deathbed of one of his men, reflected, “I can never forget how tenderly he spoke of his wife, saying he did not know how to appreciate her till the war took him from her.”

As well as offering words of comfort and urging the unconverted to seek salvation, so that they might enter immortality, chaplains – as well as nurses and other hospital personnel – performed an important service for bereaved families far away. By recording last words and witnessing deaths, chaplains could provide small crumbs of consolation for grieving relatives, reassuring them that their son, husband, or brother had died peacefully in the hope of Christ. Chaplains also performed the final service, conducting funerals for those who succumbed to their wounds, then relaying information about the words spoken and the location of the final resting-place to the men’s families.

Chaplains also found themselves taking on far more mundane, practical duties beyond their official spiritual remit. They were frequently engaged in letter-writing for those too ill to hold a pen, and often acted as postmaster for the hospital, collecting and distributing mail. Some acted as unofficial librarians, handing out literature to bored convalescents. Usually this was of a religious or moral tenor, but some chaplains were happy to hand out novels and newspapers. Charles Humphreys, understanding that unoccupied minds could easily fall into despair and desolation, took delight in sharing his collection of games and puzzles with the men under his care. Acting as librarians and postmasters gave chaplains another opportunity to stop and talk with the patients, and to pass on a few words of religious comfort as they passed through the wards.

Sometimes the work was physical, and exhausting. Chaplains, in the short-staffed and overcrowded hospitals, were frequently enlisted to help lift patients, carry supplies, and erect temporary structures. Some performed basic medical procedures like dressing wounds. Just like their counterparts on the battlefront, hospital chaplains had to be fit and healthy – and in the hospital they too were exposed to contagion and disease on a daily basis.

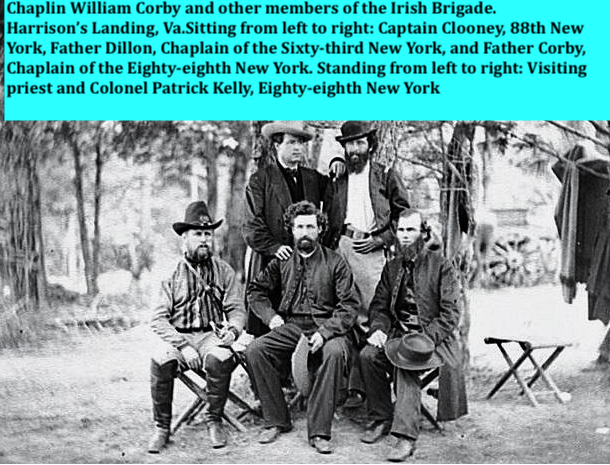

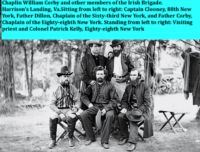

Chaplin William Corby and other members of the Irish Brigade.

Harrison’s Landing, Va.Sitting from left to right: Captain Clooney, Eighty-eighth New York, Father Dillon, Chaplain of the Sixty-third New York, and Father Corby, Chaplain of the Eighty-eighth New York. Standing from left to right: Visiting priest and Colonel Patrick Kelly, Eighty-eighth New York. Courtesy of the LOC

Even though they were not on the front lines, hospital chaplains could not escape the carnage of the Civil War. They were forced to confront gruesome wounds and to become hardened to the screams of the dying and the overpowering smells of gangrene and decay. William Corby, decades after his wartime service had ended, could still recall vividly the tangle of hastily-amputated legs, arms, hands, and feet piled up outside one hospital. “The picture can be compared with nothing but a butcher shop, or slaughter-house, where meat is cut and piled up,” he wrote.

A chaplain’s work was harrowing, improvised, and all too often underappreciated. Charles Humphreys spoke frankly of his coping strategy for dealing with the unpredictability and tribulations of the job. “If there is any single rule that runs through all my work,” he concluded to his friend Edward Hall, “it is this: to be kind to all…I think my work will be surer if I do not assume any premature dignity or unwarranted authority, but trust to the pervasive influence of charity and love.”