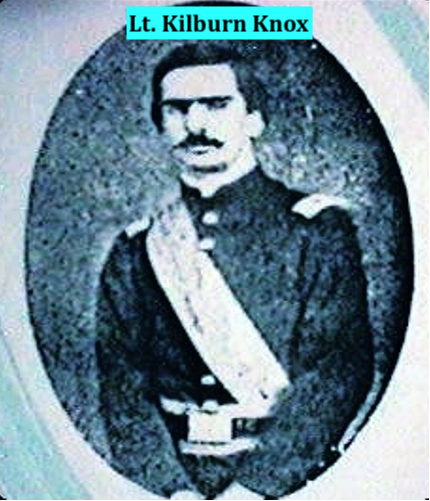

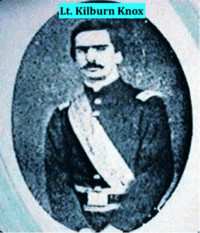

Rare 17th Corps Vicksburg Medal of Honor Awarded to Lt. Kilburn Knox US Regular Army 13th Infantry and Witness at the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators’ Trial

$9,000

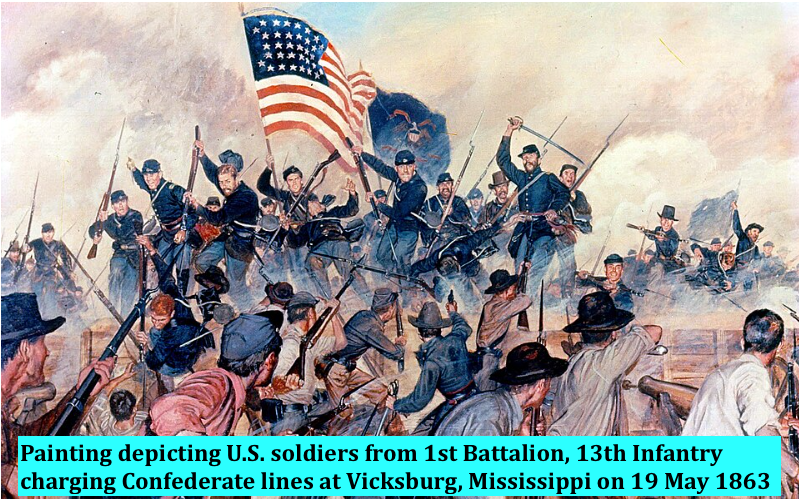

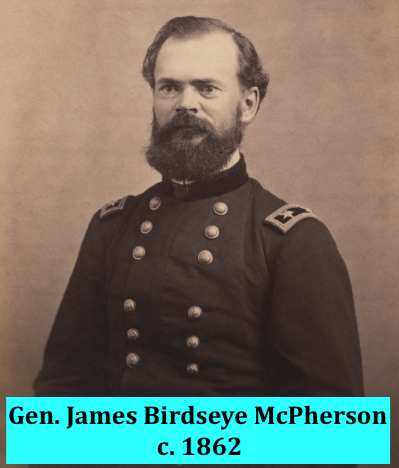

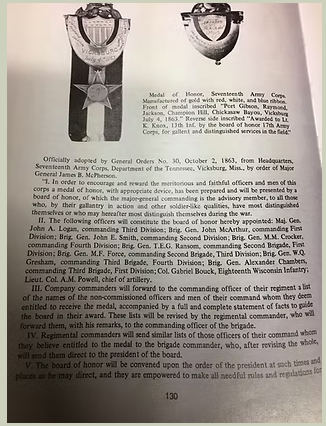

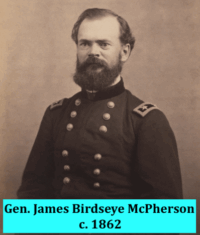

Rare 17th Corps Vicksburg Medal of Honor Awarded to Lt. Kilburn Knox US Regular Army 13th Infantry and Witness at the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators’ Trial – After a siege of more than six weeks, the city of Vicksburg fell on the 4th of July 1863 to Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant’s Union forces. The honor of leading the victorious troops into the captured stronghold fell to General James B. McPherson’s 17th Corps of the Army of the Tennessee. As commander of the Union’s occupation forces at Vicksburg, McPherson, on the 2nd of October 1863, authorized a medal to be awarded to officers and enlisted men of the 17th Corps who displayed “gallant and distinguished service in the field.” Sometimes called the “medal of gold,” it remains among the rarest of Civil War memorabilia. General Orders Number 30 – by Order of Major General James B. McPherson to encourage and reward meritorious and faithful officers and men of this corps. One of the few sanctioned wartime decorations given to Union soldiers during the war which continued to be issued at least to the summer of 1865, including noticeable service actions taken on the Atlanta Campaign. Options were for the medal to be either gold or silver, but no reason for one or the other. The medal was designed and created by the famed jewelers, Tiffany. Exactly how many and to whom the medal was awarded is unknown. There are two known recipients were Major L. S. Willard, McPherson’s senior aide-de-camp. (He and others of McPherson’s staff accompanied his body to Clyde, Ohio after he was killed during the opening rounds of the Battle of Atlanta.) Three weeks later, Willard wrote his friend and comrade Lt. Augustus. C. Blizzard, also a recipient of the medal.

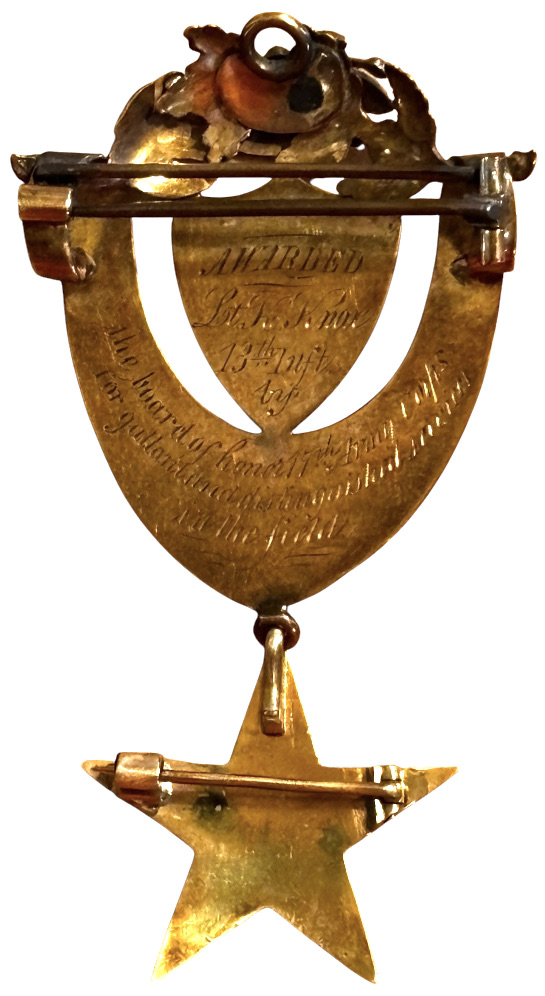

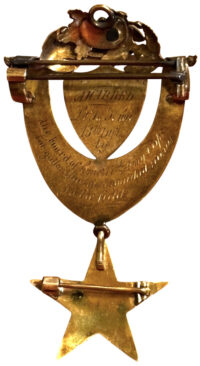

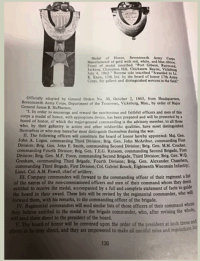

This 17th Corps Medal of Honor, constructed of gold, has a five-pointed star suspended from a curved, crescent; the star has engraved in a raised circle, in the middle of the star:

“17th”

In the middle of the crescent from which the star is suspended, is artfully engraved with the following:

“VICKSBURG

July 4th, 1863”

On the left upper limb of the crescent is engraved:

“Chickasaw Bayou / Champion Hills”

On the right upper limb of the crescent is engraved:

‘Port Gibson / Raymond / Jackson”

A patriotic shield straddles between the two arms of the crescent. Across the top of the crescent is a reinforcing bar over which is a T-pin for attachment to the recipient’s coat; atop this pin bar is a floral motif cast, decorative element with a ring to utilize attachment to a necklace. On the back of the patriotic shield is engraved:

“AWARDED

Lt. K. Knox

13th Inft

by”

Continuing along the back side of the crescent:

“the board of honor 17th Army Corps

for gallant and distinguished service

in the field”

The star is suspended by a hook beneath the crescent and has its own separate T-pin for attachment to a coat or hat; the star could ostensibly be removed to be separately attached.

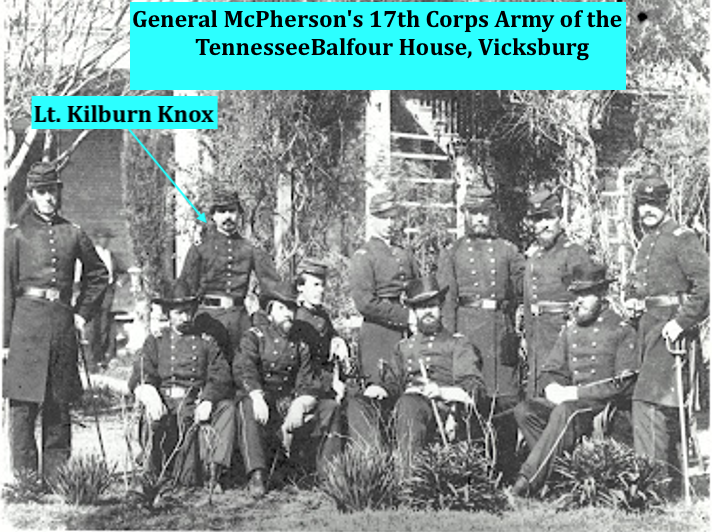

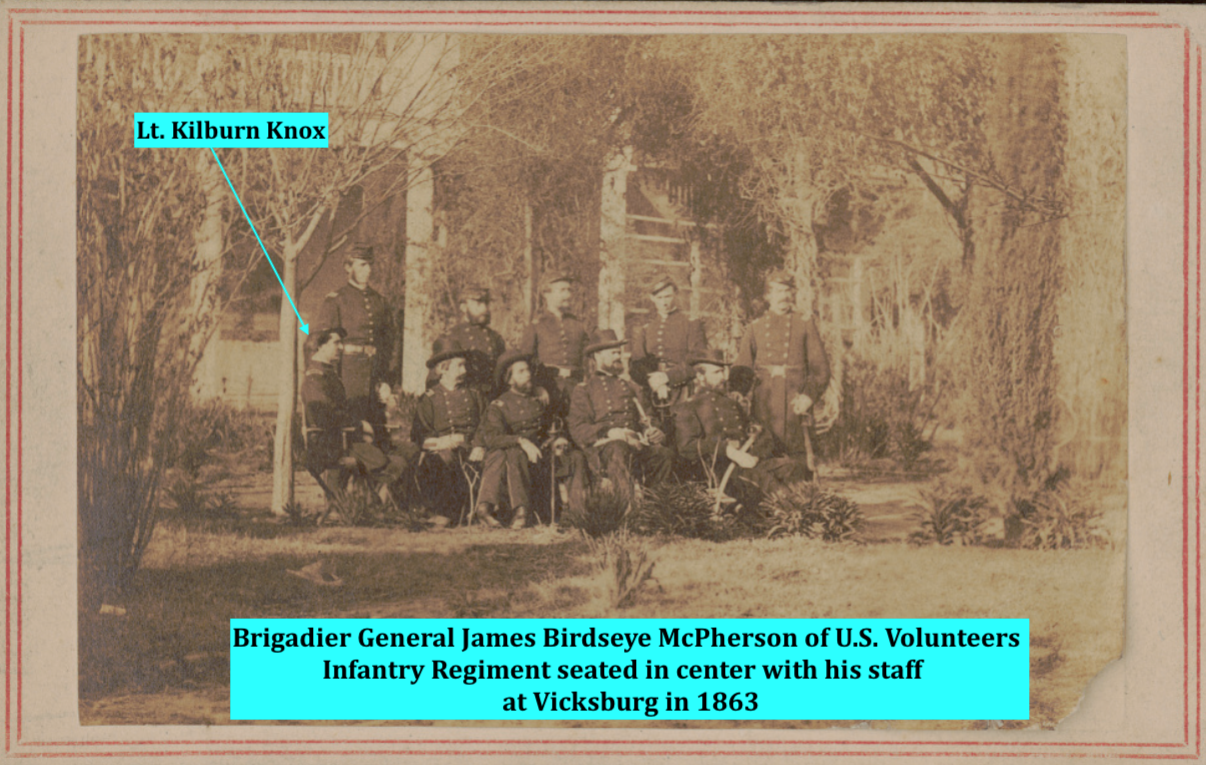

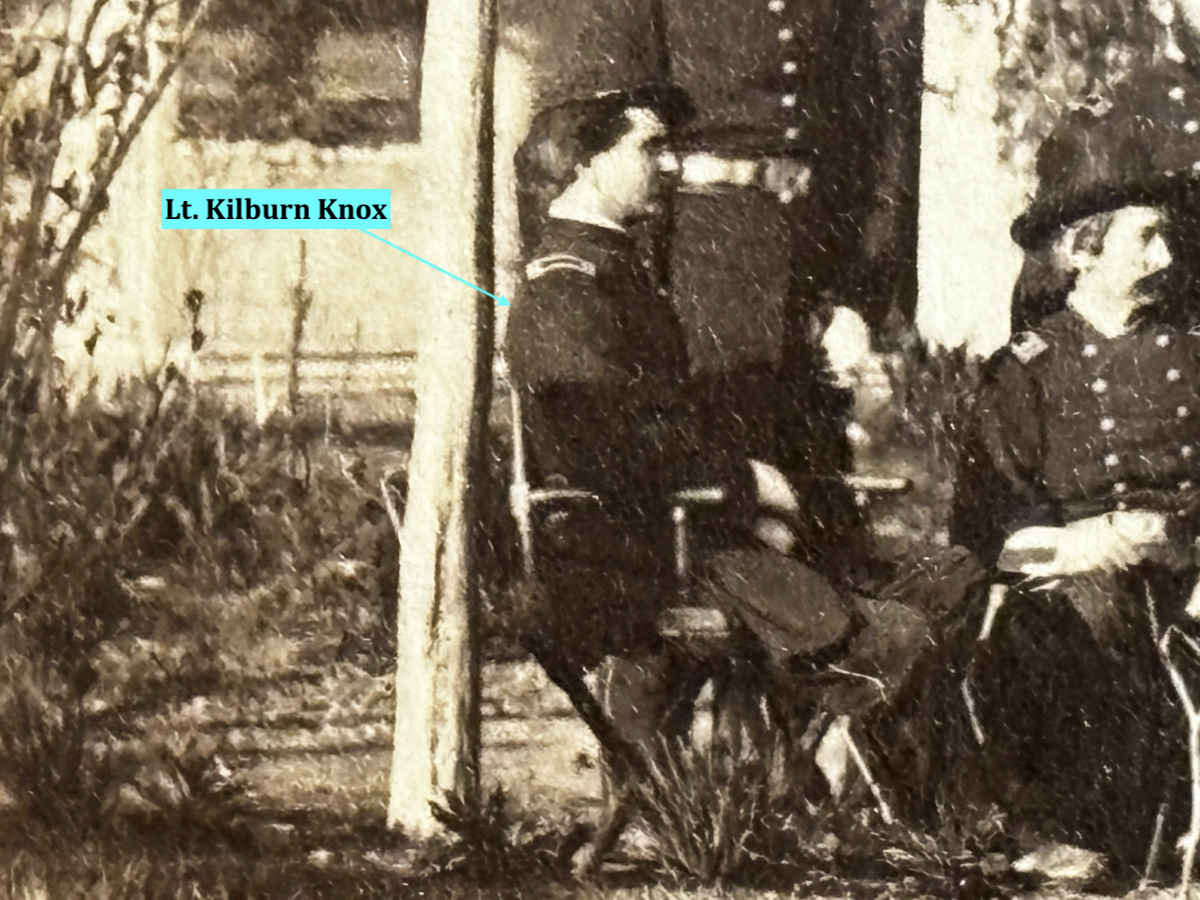

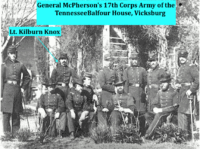

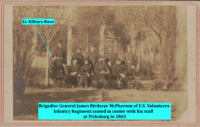

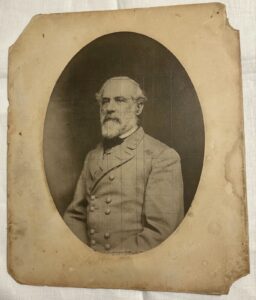

Accompanying this extremely rare medal, are two significant CDVs. One of the CDVs depicts Gen. McPherson, in an outdoor setting, with his staff, in front of an antebellum house in Vicksburg. In the image, Lt. Knox is seen sitting at the far left of the other officers, wearing a single-breasted frock coat and a kepi cap. The back mark on this image states:

“D.P. BARR

Army Photographer

PALACE OF ART

Vicksburg, Miss.”

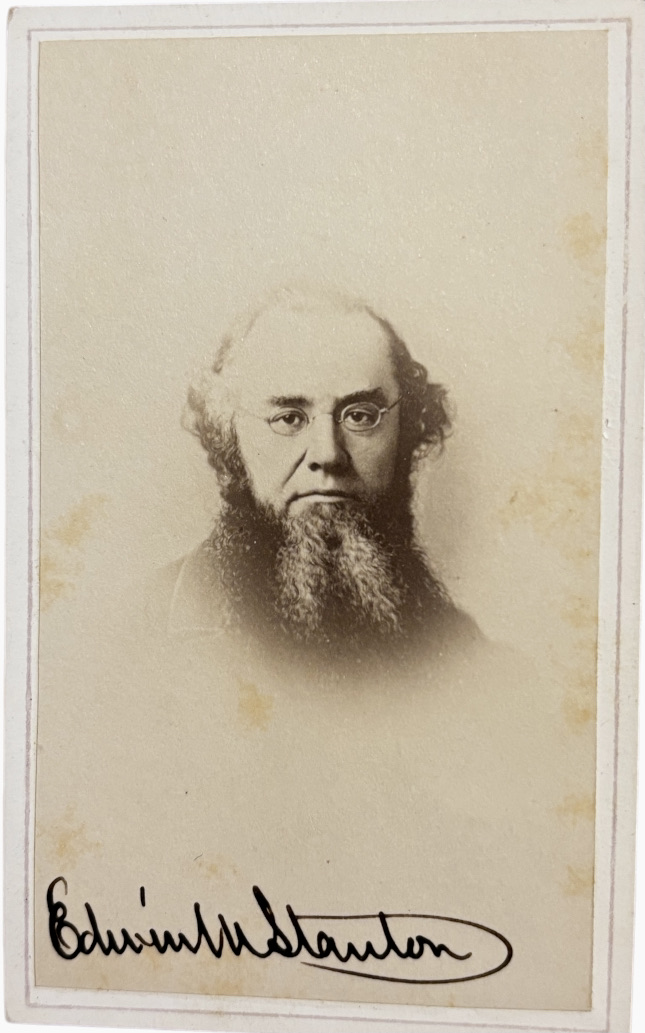

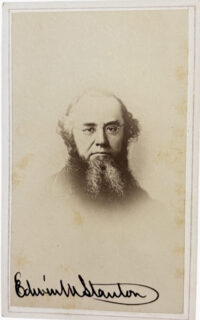

Also accompanying the medal is a second CDV that depicts an image of Civil War period, Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton; this image is autographed by Stanton, on the bottom of the front of the image; there is no back mark on this image.

The medal measures: H – 2.5”; W – 1.5”; the medal remains in excellent condition.

Kilburn Knox

Residence was not listed.

Enlisted as a Private (date unknown).

On 4/24/1861, he mustered into Pennsylvania Commonwealth Heavy Artillery.

He was Mustered Out on 6/9/1861

On 5/14/1861, he was commissioned into US Regular Army 13th Infantry.

He resigned on 4/1/1869

Promotions:

- 1st Lieut 5/14/1861 (As of 13th US Army Infantry)

- Capt 5/14/1864

- Major 7/22/1864 by Brevet (Atlanta, GA)

- Lt Colonel 3/13/1865 by Brevet

Died 4/17/1891

After the war, he lived in Naussau St, New York, NY

Commonwealth PA Heavy Artillery

Organized: on 4/24/1861

Mustered out: 8/5/1861

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comments |

| No unit assignments found. | ||||||

13th RA Infantry

Officers killed or mortally wounded: 3

Officers died of disease, accidents, etc.: 7

Enlisted men killed or mortally wounded: 55

Enlisted men died of disease, accidents, etc.: 121

Ira Kilburn Knox was a native of Pennsylvania where he was born in Lawrenceville on October 23, 1842, the son of The Honorable John Knox, one of the Justice’s of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, and Adeline Kilburn. He was known as Ira Kilburn Knox at the time of his enlistment on April 19, 1861 in the Commonwealth Artillery of Philadelphia. He was assigned with his company to Fort Delaware where he remained until June 1861.

On June 9, 1861, Kilburn was commissioned a 1st Lieutenant in the 13th U.S. Infantry, commission to date from May 14, 1861. Lieutenant Knox was transferred to Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, Missouri, where he was assigned to duties as drill officer for three regiments of volunteers. He then went on recruiting and mustering duty in Iowa. He was transferred to the Army of the Tennessee where he served in the Commissary Department under Major General William T. Sherman; he was promoted Captain on May 14, 1864. Kilburn was then assigned to the staff of Major General James Birdseye McPherson. He was brevetted Major in the Regular Army on July 24, 1864 for gallant and meritorious service at the Battle of Atlanta on the recommendation of General John Logan. He was with General McPherson at the time of his death and accompanied the General’s remains when they were returned to Ohio for burial. He returned to duty and participated in the battles of Jonesboro and Lovejoy Station.

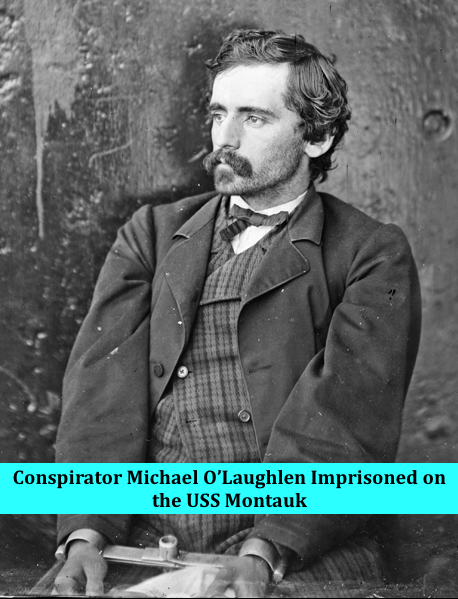

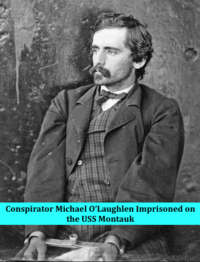

In September 1864, he was ordered to Washington D.C. where he was assigned to the staff of the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, in the Commissary General’s office. He was brevetted Lieutenant Colonel on March 13 1865. On April 15, 1865, he was assigned to duty as military aide to President Abraham Lincoln, which appointment was nullified by the death of the President. Kilburn Knox was called to testify, at the trial of John Wilkes Booth, in the assassination of President Lincoln, as a witness in the portion of the trial of the conspirators that dealt with the defendant Michael O’Laughlen. O’Laughlen was a childhood friend of John Wilkes Booth when both were residents of Baltimore, Maryland. O’Laughlen had enlisted in the First Maryland Infantry in the Confederate Army in 1861 and served until late 1862 when ill health forced him to resign and return to Maryland. John Wilkes Booth had drawn him into the initial conspiracy, which was to kidnap President Lincoln. The plot to kidnap the President failed and O’Laughlen returned to Baltimore from the Capitol. Several weeks later, he was summoned by Booth to meet with him in Washington, DC and was present in the city on April 13. At that time, Knox, as an employee of the War department, was present at Secretary Edwin Stanton’s home, on the evening of April 13th during the grand illumination of the city. Knox spoke of encountering a man on the steps of the Secretary’s house. While fireworks were being shot off, the man twice asked if the Secretary was in, to which Major Knox replied he was. Knox stated that the man said he was a lawyer and knew Stanton well. Knox believed that the man must have been drunk since Secretary Stanton and General Grant were both standing on the steps as well watching the fireworks. The man made his way into the house after the fireworks had ended and was then asked to leave by the Secretary’s nephew, David, which he did. Knox identified the man as Michael O’Laughlen, stating, “I feel perfectly certain,” that O’Laughlen was the man he encountered. Knox’s testimony echoed that of David Stanton’s from the day before, yet countered the claims of O’Laughlen’s friends who claimed the conspirator was with them during the illumination.

Ira Kilburn Knox was a major in the Union Army during the Civil War and a witness at the trial of John Wilkes Booth’s conspirators. Knox’s testimony was a key piece of evidence that connected Michael O’Laughlen to the assassination of President Lincoln.

Civil War service

- Knox enlisted in the Union Army after leaving the University of Pennsylvania to fight in the Civil War

- After the war, he served as an aide to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

Trial of John Wilkes Booth

- Knox testified about an encounter he had with Michael O’Laughlen at Stanton’s home the night before Lincoln’s assassination

- Knox’s testimony was a key piece of evidence that linked O’Laughlen to the assassination conspiracy

- O’Laughlen was convicted and sentenced to life in prison

Later life

- Knox was involved in veterans’ affairs in New York

- He became a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion (MOLLUS)

Knox was later appointed Assistant Secretary to President Andrew Johnson and served in that position until August 1865. At that time, Kilburn Knox reverted to his regular army rank of Captain and returned to service with the 13th U.S. Infantry and then transferred to the 22nd Infantry. He was assigned to command Fort Dakota, Dakota Territory, a position he held until he resigned his commission on April. 1, 1869.

Kilburn returned to Philadelphia. Moving to New York City, he accepted a position with the firm of Schuyler, Hartlely, and Graham. On April August 19, 1871, he married Annie Menager. When General John A. Dix was elected Governor of New York, Knox was appointed to the Governor’s staff as Commissary General and Chief of Ordnance with the rank of Brigadier General. He was much involved in veterans’ affairs in New York.

He was one of the earliest members of the MOLLUS becoming a Companion (Insignia No. 65) of the Pennsylvania Commandery on November 1, 1865. He transferred to the New York Commandery on April 30, 1877 and to the Wisconsin Commandery on October 2, 1889.

In January 1887, he was appointed Secretary and Inspector of the Northwestern Branch, National Home for Disabled Veterans at Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He became Governor of the Home on May 1, 1889. His wife, Annie, worked as a Matron of the Home. The Knox’s had a daughter, Birdseye McPherson Knox. General Knox died at the National Soldier’s Home on April 17, 1891. Annie M. Knox continued to work as a Matron at the Home until her death in 1927. Birdseye married Oscar Chrysler and they had three children, Laura Annette, Harriet Louise, and Frederick Knox Chrysler.

Conspirator’s Trial

Michael O’Laughlen on Trial

At the 1865 Conspiracy trial, prosecutors tried to show that O’Laughlen had taken steps to assassinate General Grant, who O’Laughlen allegedly believed was staying at the home of Secretary of War Stanton.

The key evidence against O’Laughlen also links him to Booth’s abandoned plan to abduct Lincoln. On March 13, Booth sent to O’Laughlen, then in Baltimore, a telegram from Washington: “Don’t fear to neglect your business. You better come at once.” Twelve days later, Booth sent another telegram to O’Laughlen: “Get word to Sam. Come on, with or without him, Wednesday morning. We sell that day for sure. Don’t fail.” Prosecutors suggested that the “business” referred to in Booth’s telegraph was the kidnapping of Lincoln and that the “Sam” referred to in the second dispatch was Samuel Arnold.

Bernard Early, an acquaintance of O’Laughlen’s, testified that he rode into Washington with O’Laughlen from Baltimore on the day before the assassination. Early said that the next day he waited with O’Laughlen at the National Hotel, where Booth had taken a room, for forty-five minutes before sending “up some cards to Mr. Booth’s room for O’Laughlen” and leaving. Most incriminating, perhaps, was the testimony of Major Kilburn Knox, who testified that about ten-thirty on the night of April 13 O’Laughlen, wearing black clothes and a slouch hat, entered the home of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and inquired of the Secretary’s whereabouts. Knox said that O’Laughlen remained in the hall for a few minutes before being asked to leave. Two other witnesses also reported seeing O’Laughlen at the Secretary’s home. Defense attorney Walter Cox argued that the prosecution witnesses were mistaken, and that on the night in question O’Laughlen innocently strolled the streets of the nation’s capital enjoying the “night of illumination,” the celebration of the Union victory that saw every public building in Washington lit with candles. Cox produced nine witnesses who supported O’Laughlen’s alibi. Cox also argued that the evidence showed persuasively that O’Laughlen did nothing to further the assassination on the night of the fourteenth, which he spent drinking at Lichau House before departing for Baltimore the next day.

The Military Commission found O’Laughlen guilty and sentenced him to life in prison. He died two years later in prison at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, a victim of yellow fever.