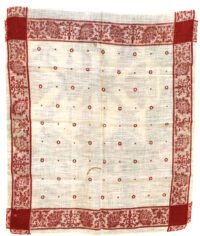

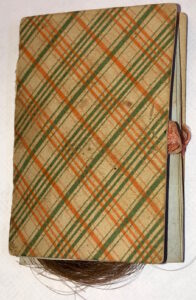

Original Civil War Period Bandana / Handkerchief

SOLD

Original Civil War Period Bandana / Handkerchief – Civil War soldiers often wore bandanas as functional accessories for protection from the elements and for practical use, such as wiping sweat, securing wounds, or even as part of their personal gear, not typically as standard uniform elements but as practical, versatile items carried by individual soldiers. While the bandana was not a regulated part of official military uniforms, it was a common and essential accessory for both Union and Confederate soldiers. Civil War soldiers wore handkerchiefs for many practical reasons, including sanitation, protection from the elements, and medical first aid. A handkerchief was a multi-purpose tool that could also serve as a sentimental keepsake from home. Handkerchiefs were not standard-issue military equipment, so soldiers used whatever cloth they could obtain. These textiles are very difficult to find now; this is only the second one that we have had. This example is made of a fine grade of printed cotton; three of the four borders are folded and sewn with a chain stitch from a treadle sewing machine. The colors remain vibrant and the cloth is in excellent condition.

Measurements: L – 18.5”; W – 15.5”

The Bandana: History’s Colorful Canvas

Posted by Connor Humphreys on April 04, 2018

Bandanas are definitely having a moment. From festival fashion to Super Bowl spectacles, bandanas have been EVERYWHERE over the past few years – and the trend shows no signs of slowing down. And why would it? We here at BANDITS may be a bit partial, but there’s no denying that bandanas have shown some serious staying power over time. These versatile pieces of colorful cloth are far from a fad, boasting a nearly 300-year history of form, fashion, and function.

Bandana Origins (Late 17th Century – Late 18th Century)

The bandana, as it is commonly known today (printed colors and patterns on square cotton fabric), traces its origins back to the late 17th century in the Middle East and Southern Asia. In fact, even the word “bandana” is thought to come from either Hindi or Urdu, both in which the word “bāṅdhnū” loosely translates as a tied or bound cloth. It was in this region that the black printing processes emerged. It involved pressing pre-carved blocks into small pieces of woven fabrics, infusing them with the earliest dyes made from indigenous plants and materials.

The most prevalent of these dyes, the Turkish Red, was originally made of madder root and alizarin (to infuse the dye into the cloth), along with as sheep’s dung, cow’s blood, and urine. It might sound like a strange (and disgusting) concoction, but this process produced a red dye that didn’t fade in the sun or upon washing – a valuable trait among garments of the day.

These square pieces of printed fabric soon began making their way to Europe in the early 18th Century by way of the Dutch East India Trading Company. Marketed mainly as women’s shawls, one of the first patterns to gain popularity was the ancient Persian “boteh” pattern (or “buta” in Indian). Boteh, a repeating pattern of curved teardrop-shaped figures, would eventually become known among European consumers as “Paisley.”

As European demand for the woven products grew, the imported fabrics from Persia and India became prohibitively expensive and became synonymous with wealth and status. At the same time, printers and manufacturers in Europe began making their own, cheaper versions of the popular patterned fabric to appeal to the masses. One town in Scotland, Paisley, emerged as a leader in European shawl production, and the name for the pattern stuck.

The Bandana in America (1770’s – 1900)

The actual bandana product (a unisex scarf or kerchief, as opposed to the feminine shawl) traces its origins to the late 1700’s in early colonial America. Under British rule, many of the popular styles of the day tended to make their way to the colonies, and the woven shawl was no different. However, as with countless other British traditions, the Americans did it a bit differently.

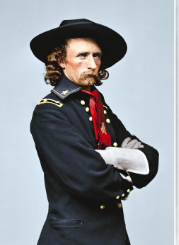

In the midst of the fight for American independence, in an effort to stem revolutionary propaganda, the British imposed a colonies-wide ban on printing. As legend has it, in an act of defiance to British rule, Martha Washington commissioned a printmaker in Philadelphia named John Hewson to print a square kerchief as a gift for her husband, George. Hewson printed the cotton fabric with images of then-General George Washington alongside military flags and cannons.

After the war was won, tales of the legendary print made their way into the public consciousness. A replica of the bandana was mass produced, became extremely popular, and the American love affair with the bandana was born. Politicians throughout the early and mid 1800’s used bandanas as campaign promotions, printing them with their names, slogans, and pictures

As the newly formed nation of the United States grew, so did the popularity and use of cotton bandanas. Their versatility as an item of clothing, along with the durability of the cotton fabric, made them treasured items among the lower and working class. Bandanas were widely used as handkerchiefs, napkins, scarves, tourniquets, slings, and even famously as a tie for a bundle of goods at the end of stick.

During the Civil War, bandanas became a functional uniform staple for soldiers on both sides. In fact, it was common for a soldier going off to war to carry his possessions wrapped up in a cotton bandana. Afterward, the newly built transcontinental railroad brought settlers and many former soldiers West. With them, the bandana emerged as an enduring symbol tied to cowboys, railroad workers, prospectors, and others that came to populate the new American landscape.