Southern Wagon Saddle Adapted For Confederate Military Use

$950

Southern Wagon Saddle Adapted For Confederate Military Use – We obtained this rare saddle in the Valley of Virginia, near Charlottesville. The saddle is in superb condition with all leather being soft and pliable and remains in near riding condition. This classic river plantation or wagon saddle was a popular, pre-war choice for riders who liked a deep seat pocket; it was the preferred choice for a gaited horse or a trotting breed and was designed to be ridden for hours. There is no horn and has exceptionally long fenders that are decoratively embossed. Originally designed for “Southern Plantation owners” to oversee their crops, with riders in the saddle for long periods of time. A well made “plantation saddle” astride a smooth gaited animal was akin to riding the “Cadillac version” of equine transportation. These saddles were not only the favorites of plantation owners, but were also the saddle of choice of country doctors, circuit riding preachers and lawyers as well as others who spent long hours on horseback, thereby necessitating a saddle that was all-day comfortable for themselves and their mounts. When the Civil War commenced, many of these saddles were incorporated for use in the Confederate army, with many being utilized for a variety of military applications. These saddles are comparable, in design, to the 1832 Artillery Saddle with it’s comparable long skirts; also, these saddles were used by teamsters who directed their teams of horses while seated in these saddles.

This saddle has thick harness leather squared skirts that are 15″ wide by 22″ long. The original stirrups, most likely during the antebellum era were the thin iron loop variety, were replaced, at the onset of the war, with wide, heavy, leather hooded, bent oak tread type stirrups, commonly seen on U.S. M1859 McClellan saddles. The leather, as mentioned, is in very good condition; the original stirrup straps and iron roller buckles remain, as does the original surcingle. This Civil War period, so-called “mule skinner wagon or train driver, Somerset plantation saddle” is extremely rare. These saddles were often used by Confederate soldiers referred to as “mule skinners”. Typically, twenty-five wagons were needed to supply a thousand men. Mule teams were usually hitched to wagons in 3 pairs with the lead pair in front, 2nd were the swing pair, then the pole (or wheel) pair, nearest to the wagon. The driver, referred to as a “mule skinner”, rode the left pole mule, which had a saddle. The driver guided the lead team utilizing a long single rein that traveled through loops on the harness. This saddle, when we initially obtained it, required only a modicum of any cleaning. The saddle has a wood frame, with long, square fenders. As detailed, the stirrups are steam bent wood. In addition, the original under-saddle, bed-ticking pad is still intact, and it remains in overall good condition, with some fraying along the front pommel area. The saddle’s leather is supple, flexible and is not dry rotted. Indeed, the saddle is intact and complete and is nearly capable of being ridden today.

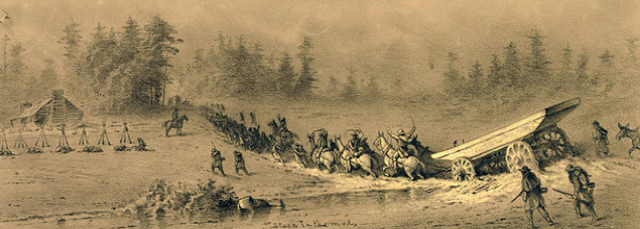

The significance of both horses and mules and the most demanding and necessary work they provided, along with their riders and wagon teamsters, to the Union and Confederate armies cannot be underestimated. Perhaps the significance of horses, mules, their handlers, riders and teamsters, during the Civil War, is more adequately captured by the following statements and overviews:

“Few appreciate the difficulties of supplying an army. If you will calculate that every man eats, or is entitled to eat, nearly two pounds a day, you can easily estimate what a large army consumes. But besides what men eat, there are horses and mules for artillery, cavalry, and transportation in vast numbers, all which must be fed or the army is dissolved or made inefficient. There is another all-important matter of ammunition, a large supply of which for infantry and artillery must be carried, besides what is carried on the person and in the ammunition chests of guns and caissons. Our men carry forty rounds in boxes, and when approaching a possible engagement take twenty more on the person. Of this latter, from perspiration, rain, and many causes there is great necessary waste. It is an article that cannot be dispensed with, of course, and the supply on the person must be kept up. The guns cannot be kept loaded, therefore the diminution is constant from this necessary waste. My division, at present numbers, will require forty to fifty wagons to carry the extra infantry ammunition. You should see the long train of wagons of the reserve artillery, passing as I write, to feel what an item this single want is.”

Alpheus Williams to his daughters

July 6, 1863

(Brig-General 5/17/1861, Major-Gen 1/12/1865 by Brevet – U.S. Volunteers General Staff)

Looking for the Confederate War

Historian Michael C. Hardy’s quest to understand Confederate history, from the boots up.

Monday, March 23, 2020

Confederate Wagon Trains, Teamsters, and Wagoneers

Over the years, I have collected quite a few volumes on the War. They include general reference works, biographies of military and political figures, books on places, and on battles. In only one of these multitude of volumes can I find one chapter on the subject of wagon trains. That would be found in Earl Hess’s Civil War Logistics, and this chapter looks at the role of wagon trains mostly on the Federal side.

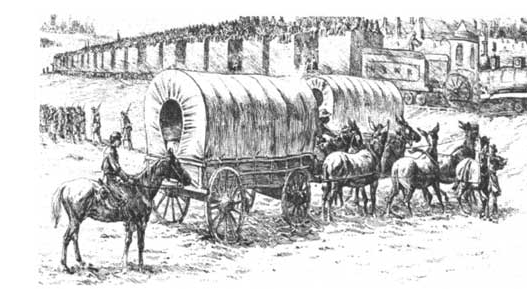

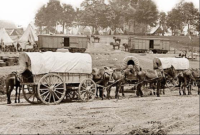

When most people think about Confederate wagon trains, the retreat of Confederate forces from the battle of Gettysburg is the primary event that pops into mind. Under the command of Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden, that wagon train of supplies and wounded stretched 15 to 20 miles (probably more) and was attacked several times by Federal cavalry. While these transportation systems are now an important piece of history, seeing a wagon or a train of wagons was a common occurrence in the 1860s.

Turning first to Army Regulations (1863, Confederate. The Federal 1861 regulations are almost identical), we find that each infantry regiment is entitled to six wagons. A textbook regiment is 1,000 men, so overall, that is not a lot of room to haul food, mess equipment, and officer’s baggage on campaign. Of course, save for the opening days of a campaign, regiments were seldom at full strength. By mid-1863, at least in my experience, a regiment had 400-600 men. Plus, the medical department for each regiment “is allowed two four-wheeled, and the same number of two-wheeled ambulances; and one wagon for the transportation of hospital supplies.” Federal regulations actually specified the size of the wagon – 22x41x114 inches, inside measurement. It seems this was omitted from Confederate regulations. Of course, we know that wagons were always in short supply for the Confederacy. The wagon train for a regiment was under the command of the colonel of that regiment. The actual commander of the wagon train was the wagon-master, who, according to regulations was under the command of the quartermaster’s Department. The wagon-master had command over the teamsters or wagoneers. Strangely enough, a “wagon-master” is not a rank that I have encountered on the Confederate side.

Digging a little deeper, Scott’s Military Dictionary (1861) tells us that for “each regiment of dragoons, artillery, and mounted riflemen in the regular army there shall be added one principle teamster with the rank and compensation of quartermaster-sergeant and to each company of the same two teamsters, with the compensation of artificers.” (610) It is interesting that there is no mention of the Infantry.

So how well do these numbers stand up to what actually happened? That, my friends, is a hard conclusion to reach. Just how many wagons were with each regiment? Five to six seems to be the rule. In August 1862, when Col. John B. Palmer was ordered to move his regiment, the 58th North Carolina Troops, from the present-day Johnson City area to Cumberland Gap, he was instructed to take just five wagons (Hardy, The Fifty-Eighth North Carolina Troops, 39). A field officer in Colquitt’s brigade (ANV), writing in December 1862, complained that his brigade (five) regiments only had thirty-seven wagons, six of which were worn out. He needed six foraging wagons, but only had one.” (Glatthaar, General Lee’s Army, 212) What I do now know is this: does the number of wagons, both for Palmer and Colquitt’s brigade, include the ambulances and wagon for transporting medical supplies? Or, were those two always separate?

Peter Wellington Alexander, a correspondent for several war-time Southern newspapers, fills us in with several important observations early in the war. Writing in December 1861, he has this to say about the Quartermaster’s Department: “It is the duty of this department to provide transportation, fuel and quarters for the men, and forage for the teams and staff and cavalry horses. The rules adopted in the Army of the Potomac [later Army of Northern Virginia]—and the same is true, I presume, elsewhere—had been to impress all the transportation and forage in the counties adjacent to Manassas. Where the owners were willing to part with their teams or provender, they received pay for them; otherwise, they were seized and the owners turned over to the government for remuneration. There cannot be fewer than 1,500 to 2,000 wagons, and six to 8,000 horses, in the service of the Quarter-Master’s department for that division of the army… At first drivers were impressed with the wagons. Now, they are detailed from the ranks, of the army—young men who have no experience in driving and who complained that they did not enlist to drive wagons. They were required to alternate, and thus every day or two there was a new driver, who was ignorant both of the ability and disposition of the horses, and who soon teaches them bad habits.” (Styple, Writing and Fighting the Confederate War, 59)

There is a lot to unpack, at least for early war, in that statement. The Confederate army would have had next to no wagons at the start of the conflict. Maybe a handful found at various captured military post throughout the South, but really not enough to provision and equip the army. So, military officials bought or impressed both wagons and teams. I’m sure this is not only true for Confederate forces in Virginia, but Tennessee, Alabama, and South Carolina as well.

Second, the drivers of these wagons came from the ranks. For many who write about the war, we often see long wagon trains driven solely by impressed or hired slaves/free people of color. That might be true, especially after mid-1864, but not entirely. I’ve noticed over the years quite a few men detailed from the ranks to drive wagons. In the 39th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, I documented fourteen men who served as teamsters. The average age was 36. (The youngest, fourteen, the oldest forty.) The records are really spotty, as with most Confederate regiments. All of these men save two were listed as teamsters when the compiled service records of 39th Batt. VA Cav. end in December 1864. Only one of those men, Pvt. Alexander J. Ramsey, was listed as being sick and wounded prior to being assigned as a teamster. I can’t really say that those who were disabled or unfit to march with the infantry were assigned to this duty. Another interesting example from the 39th Battalion is Pvt. Anthony S. Butts. Private Butts was conscripted into the Confederate army in 1863, and was assigned to ANV headquarters staff. For the rest of war, right up until Robert E. Lee arrived in Richmond on April 15, 1865, Butts was driving Lee’s personal ambulance. Of course, the 39th Battalion Virginia Cavalry did not function as a traditional cavalry command. Many of these men detailed as teamsters, like Butts, were serving in other commands.

Did Black men serve as teamsters? Yes. Where they prominent in that role? I really can’t say. There were a couple of attempts in 1864 to get detailed men back in the ranks. Marion Hill Fitzpatrick wrote in November 1864 that “Jeff Davis recommends the calling out of Forty Thousand able bodied negroes [for teamsters].” (McCrea, Red Dirt and Isinglass, 528) Obviously, some of them could have been used to replace white men detailed as teamsters. Some regiments did have Black teamsters. The 30th Virginia Infantry had six. (Pamplin Historical Park) Tim Talbot has an account on his blog of a member of the 1st Maine Cavalry capturing (in late 1864) ten Confederate wagons loaded with provisions, along with their “drivers (all colored men).”

How did the men in the ranks feel about the men detailed as teamsters? Another good question. Joshua Lupton, 39th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, was detailed to serve as the wagon master for ANV Headquarters staff. His brother John thought Joshua’s assignment was an easy one. All he had to do was “issue forage to General Lee’s horses twice a day.” (Hardy, Lee’s Body Guard, 25) Undoubtedly, there was some resentment over this “easy assignment.” At Appomattox, when the time came to surrender, those men who had been detailed as teamsters were sent back to their regiments to march in the proceedings. Brigadier General James H. Lane felt that these men should all be placed in a group together. “I did not wish to surrender any but those brave fellows who had followed us under arms,” he wrote after the war. (Fayetteville Observer, June 8, 1897.)

Valor (Bullets & Beans)

By Thomas Venner

Posted on Friday, December 24th, 2010

The 7th Tennessee Regiment may have had as many as 17 wagons

The Writing Process — Tennessee Valor (Bullets & Beans)

I enjoyed 5 hours of research trying to determine the answer to two questions;

1) How many men supported the combat soldiers?

And 2) how many wagons did the 7th Tennessee possess as the regiment marched from Virginia to Gettysburg?

I read somewhere (I can’t remember where) that during World War II, for every G.I. who fired his weapon there were 15 others in support. This led me to wonder, what did the riflemen and the officers of the 7th Tennessee have in logistical support? I plunged back into the 7th’s personnel records seeking Tennesseans who had other duties besides standing upon the firing line. Surprisingly, I found many–48 to be exact. Mathematically, that give me a simple number to answer the question of men in support—there were 48 noncombat positions to support the 282 men who advanced into the killing zone.

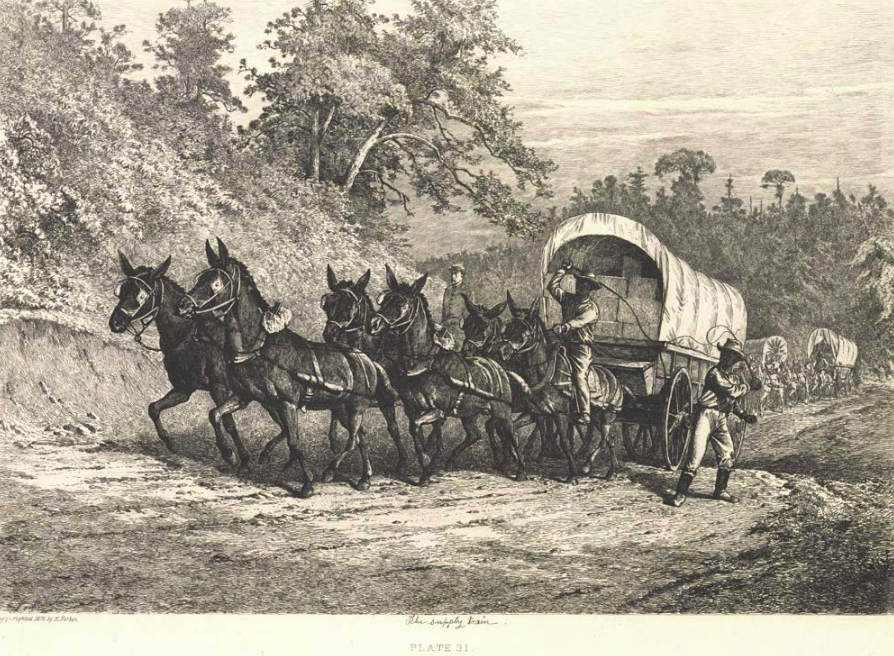

As I wrestled with the wagon question, it became obvious I did not know how much a Civil War-era wagon could hold. The answer came from someone who knew how to supply an army on the march–William T. Sherman. He noted during his trek to the sea, “An ordinary army-wagon drawn by six mules may be counted on to carry three thousand pounds net, equal to the food of a full regiment [1000 men] for one day.” However, he did mention that few wagons actually carried that weight due to the poor condition of the roads, but that does give us a general idea.

It has been said that following Gettysburg, Lee’s wagon train of wounded stretched for 17 miles. The 7th Tennessee’s wagons were part of that massive convoy, and some of them contained wounded Tennesseans—27 as recorded from the Personnel Records. Again, I delved into the list of noncombat soldiers and determined there were 13 men identified as “Teamsters”, another listed as “Ambulance Driver,” and another named as “Forage Train Teamster.” There also was one soldier listed as “Wagon Master” and 2 men named as “Teamster Wagon Masters”. The wagon master would have controlled the regiment’s wagons, rather than driving a vehicle. Since it was only necessary for one teamster to handle a 4-horse or 6-mule team, and because Lee wanted every man who could carry a weapon on the battle line, that leads one to assume the 7th Tennessee had 17 vehicles.

How would 17 wagons be distributed?

One is an ambulance; that is certainly the vehicle which would carry the ambulance driver, plus Surgeon James L. Fite and his 2 assistants.

The other 16; how about one per company? That would take 10 more, leaving 6.

Another one seems apparent; a Regimental Forage wagon, driven by the forage train teamster and commanded by a regimental forage master.

We can figure Colonel John A. Fite would get one.

I’m suggesting that the Regimental Quartermaster department (led by Cpt. Marcus L. Walsh) would get another.

That leaves just three; could they have gone to the Regimental Blacksmith, the Regimental Commissary, and to the Regimental Ordnance?

I will keep searching!

One last note. When US General Kirkpatrick’s cavalry swept down upon the Confederate wagon train outside Greencastle, PA the 7th Tennessee lost two wagons and two teamsters, and five wounded soldiers to the Yanks; a total of seven men captured: Teamsters John Canary and Thomas Hatcher, and the following wounded; 3rd Lt. Thomas L. Jennings (Co. F), Cpl. J.P. Bashaw (Co. I), and Pvts. Thomas Brasnaham (Co. C), John K. Lane (Co. K), and James L. Seat (Co. K).