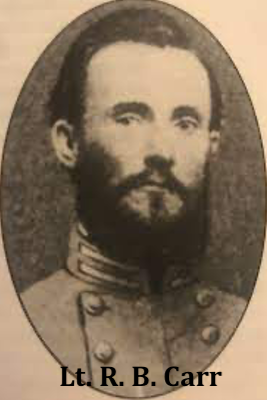

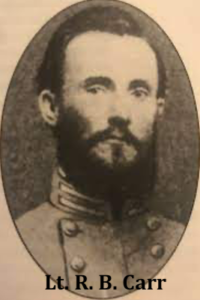

Poignant Letter Written by 1st Lt. Robert B. Carr, Co. A, 43rd NC Infantry from the Union Prison at Pt. Lookout, Md. – Carr Became a Member of the Famed Immortal 600

SOLD

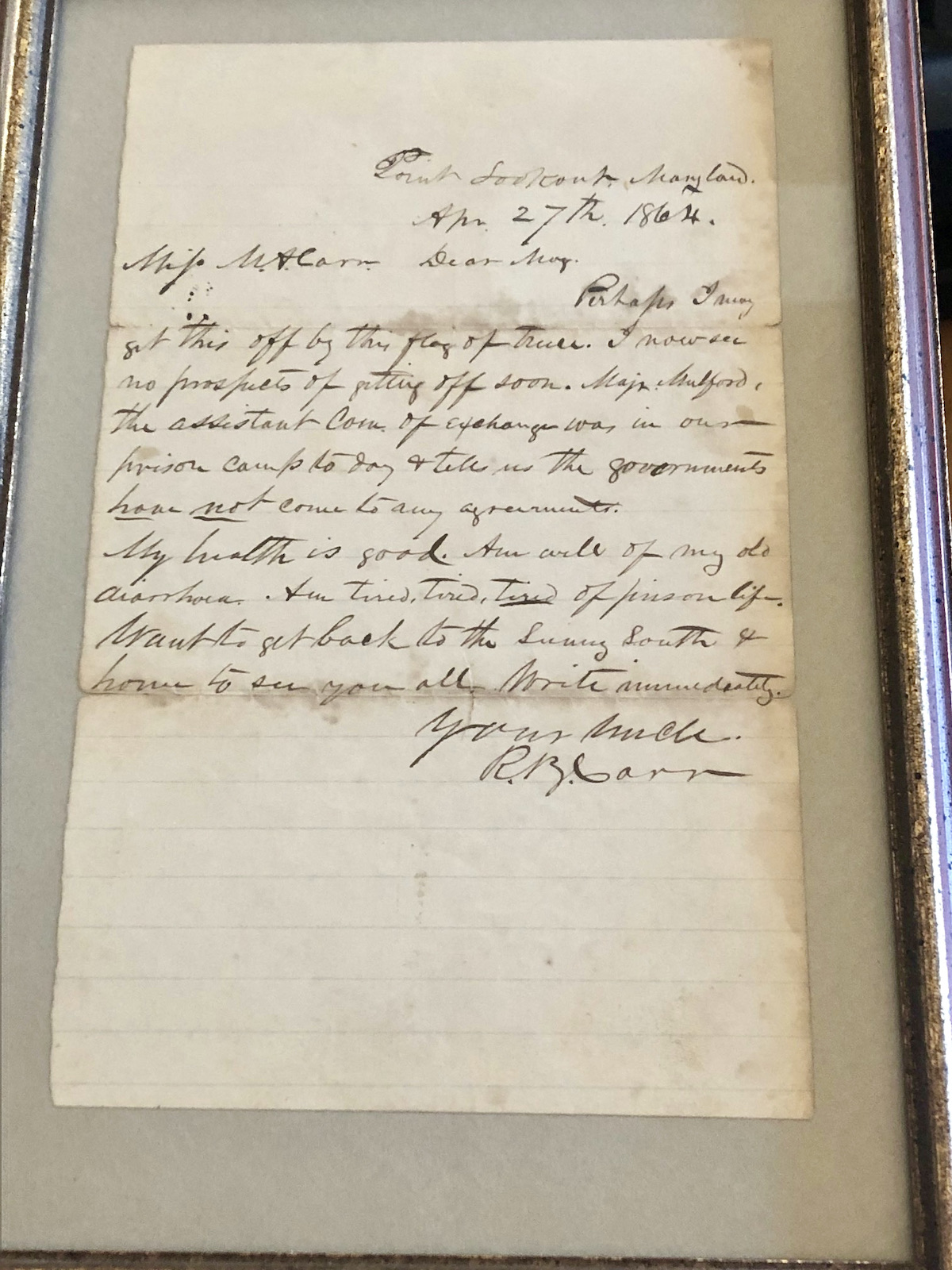

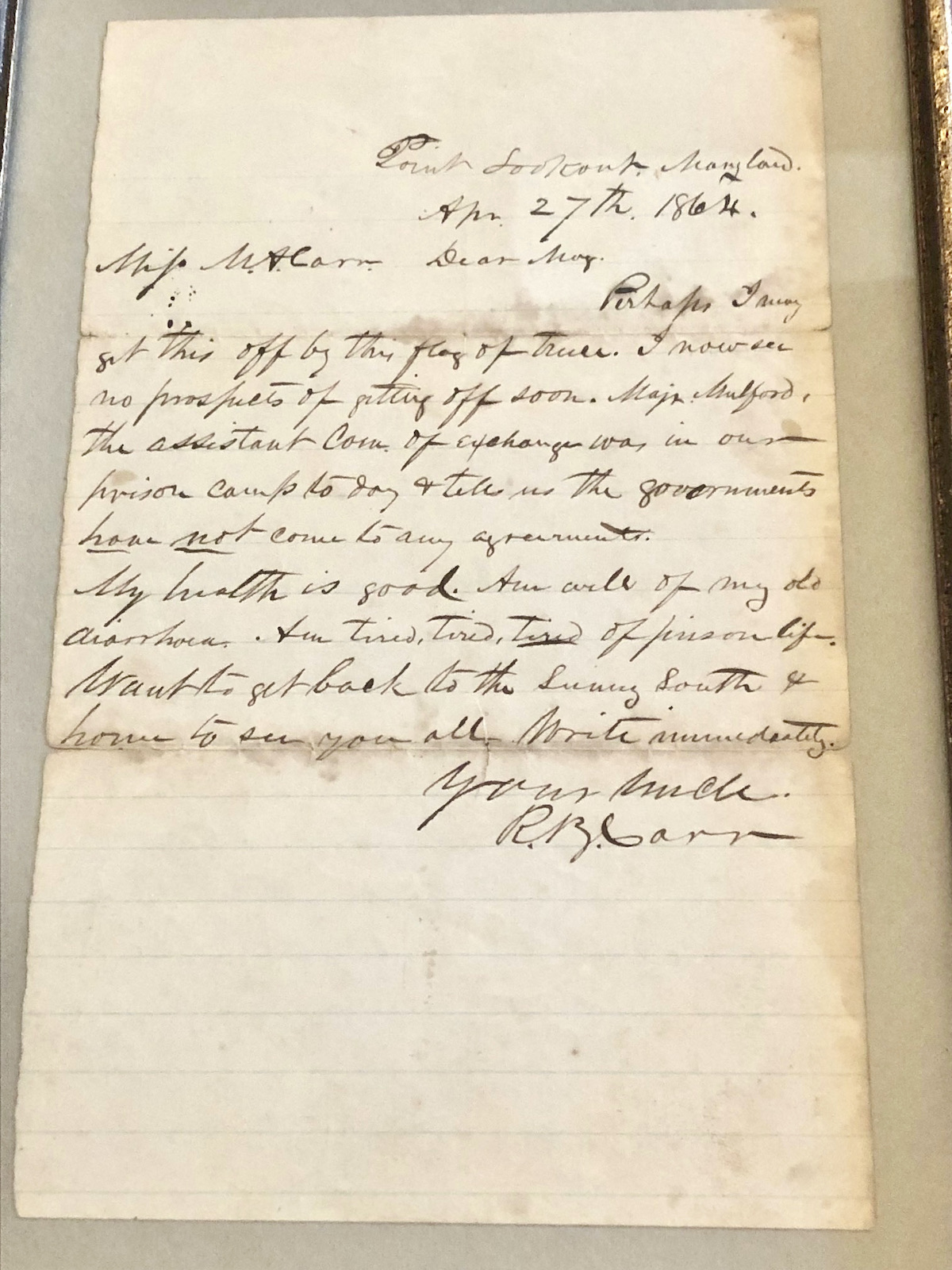

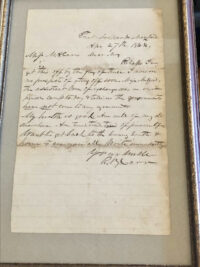

Poignant Letter Written by 1st Lt. Robert B. Carr, Co. A, 43rd NC Infantry from the Union Prison at Pt. Lookout, Md. – Carr Became a Member of the Famed Immortal 600 – This sadly desperate letter was penned by Lt. Robert B. Carr, to his niece, Mary Carr, on April 27, 1864. Carr sustained a shrapnel wound to his foot at Gettysburg, on July 3, 1863 and was subsequently captured by Union forces, the following day. He was initially transferred to a Federal hospital in Frederick, Maryland, then transferred to Ft. Delaware, as a Confederate POW; on July 20, 1863, Carr was moved to the Union prison for Confederate officers on Johnson’s Island in Ohio. Carr would again be transferred, on February 9, 1864, back to Point Lookout, Maryland and then, on June 23, 1864, back to Ft. Delaware. Ultimately, Carr was shipped to Hilton Head, South Carolina, and under the directives of Gen. John G. Foster, Commander of the Federal Department of the South, was one of 600 imprisoned, Confederate officers sent to Morris Island. This group of officers would become known as the Immortal Six Hundred. There were 600 Confederate officers who were held prisoner by the Union Army in 1864–65. In the summer of 1863, the Confederacy passed a resolution stating that all captured African-American soldiers and the officers of colored troops would not be returned. The resolution also allowed for any captured, white officer of colored troops to be executed and any captured African-American soldier be sold into slavery. The resolution caused a breakdown in the exchange of captured soldiers as the Union demanded all soldiers be treated equally. The Immortal Six Hundred were one group of officers who could not be exchanged** (See additional information on the Immortal 600 attached to this posting.)

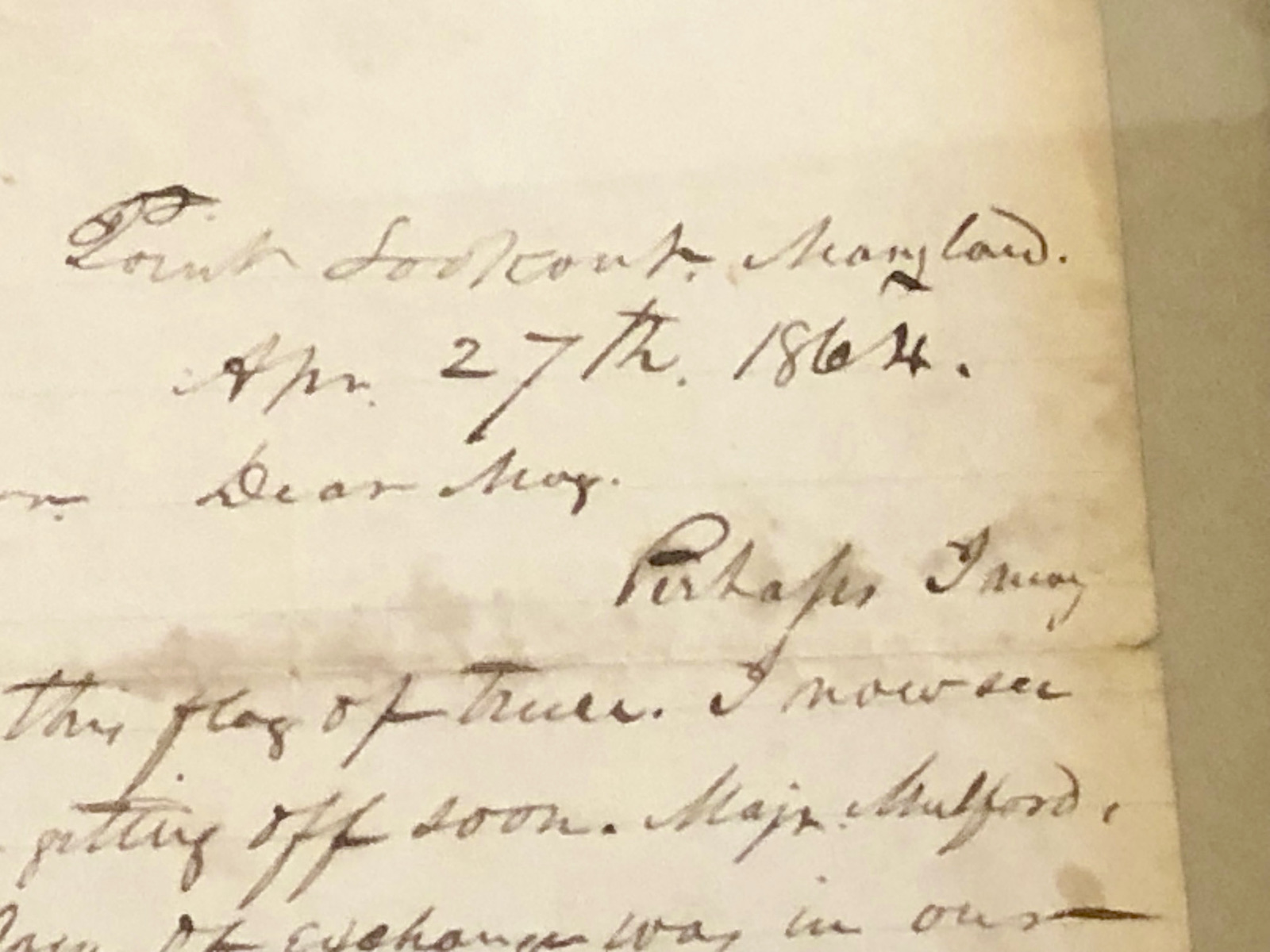

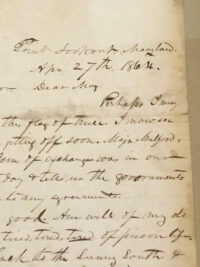

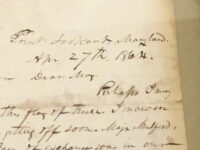

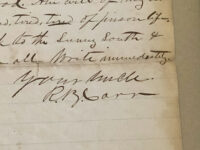

Lt. Carr, wrote this letter to his niece, Mary Carr, while he was incarcerated as a POW, at Point Lookout, Maryland; in this poignant letter Carr writes, as follows:

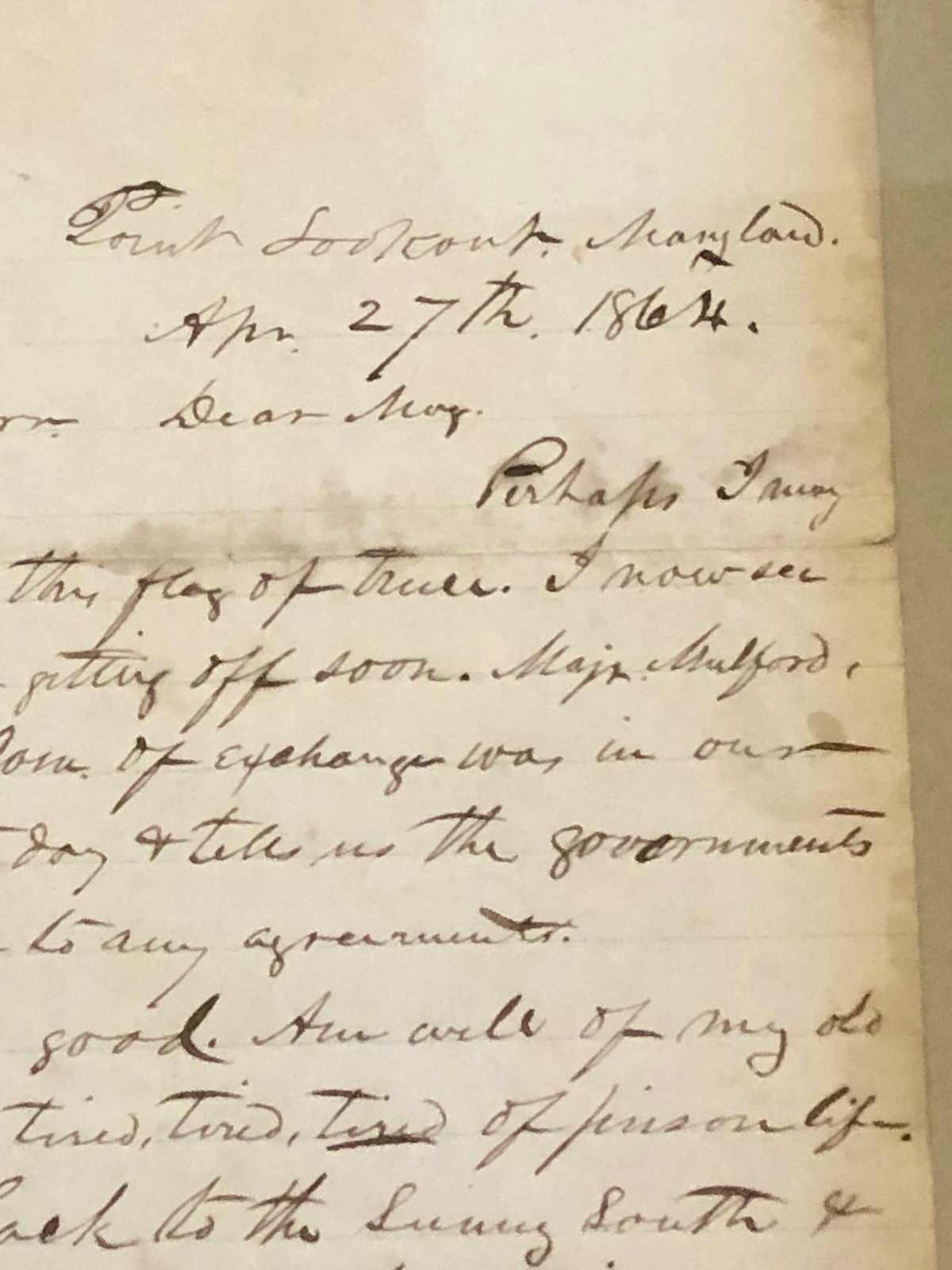

“Point Lookout, Maryland

Apr 27th, 1864

Miss M.A. Carr Dear Mary

Perhaps I may

get this off by the flag of truce. I now see

no prospects of getting off soon. Major Guilford,

the assistant Com. Of exchange was in our

prison camp today & tells us the governments

have not come to any agreements.

My health is good. Am well of my old

diarrhea. I’m tired, tired, tired of prison life.

Want to get back to the Sunny South &

home to see you all. Write immediately.

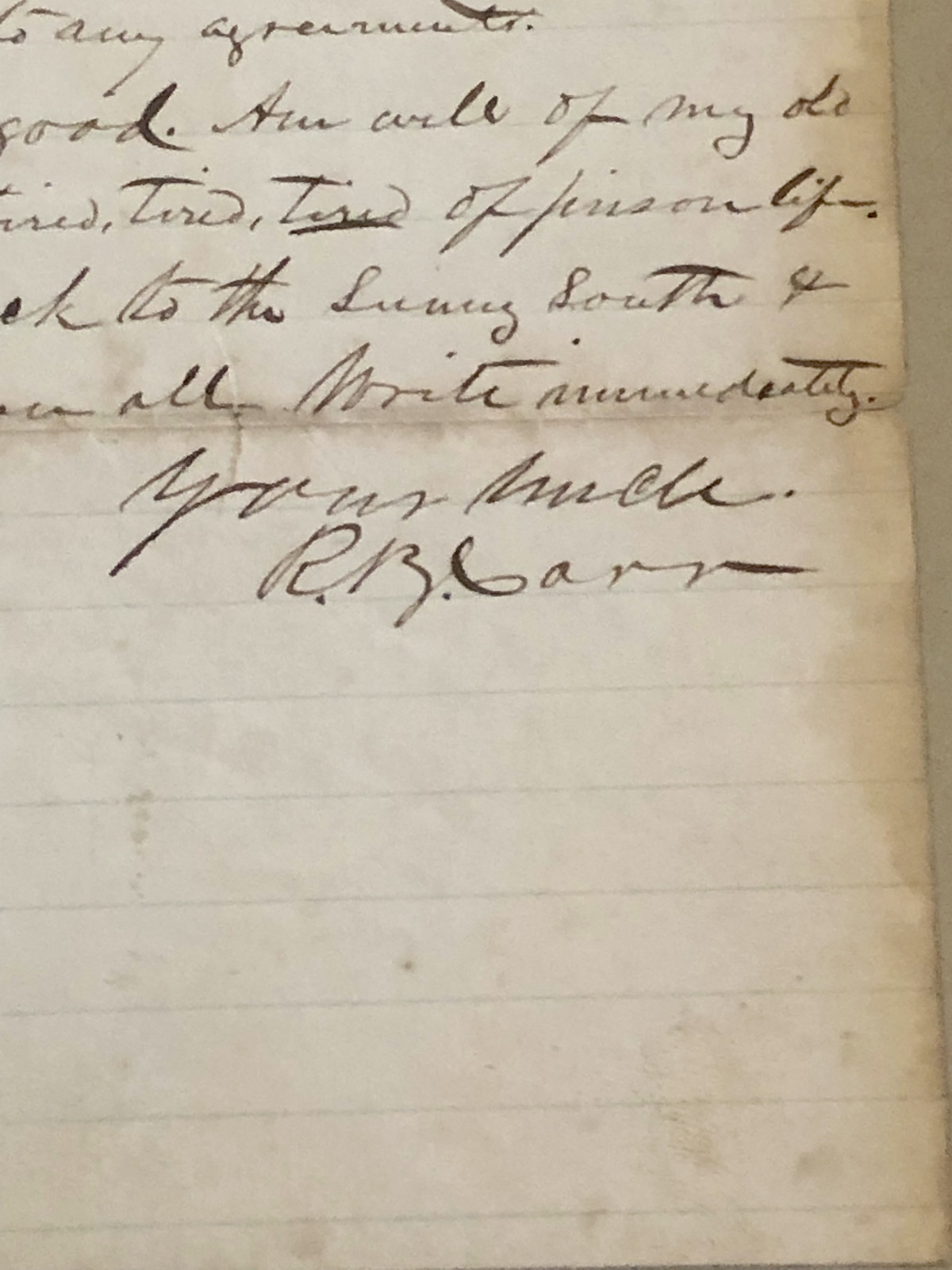

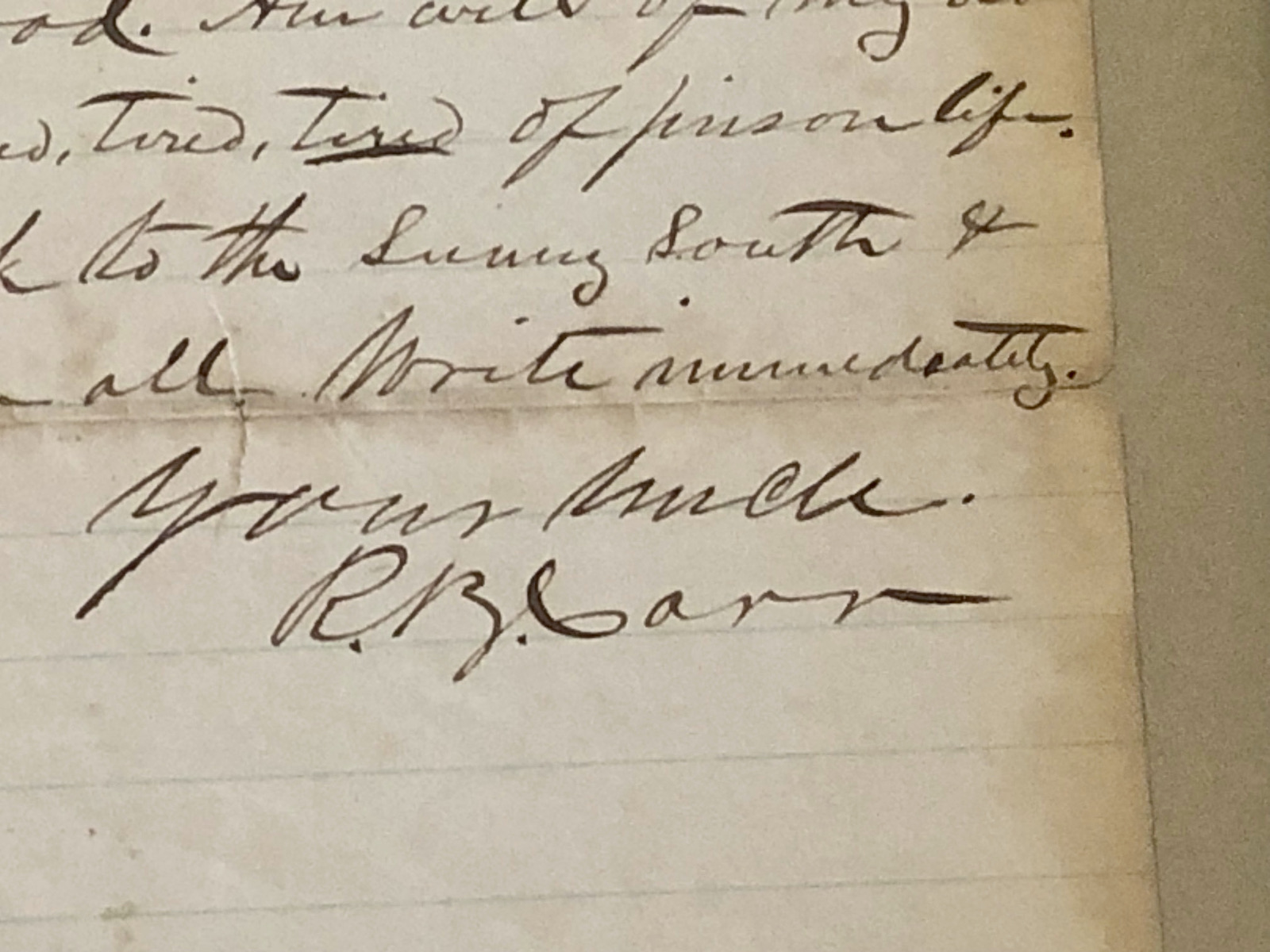

Your Uncle,

R.B. Carr”

Robert B. Carr

Lt. Carr would survive his lengthy imprisonment, as well as enduring his time on Morris Island; he would then be transferred to Ft. Pulaski, in South Carolina, where conditions for imprisoned Confederates were deplorable. Carr’s health apparently declined precipitously, as he died from the ravages of chronic diarrhea, at Hilton Head, SC, on July 3, 1865.

This is a significant, short letter written by a North Carolinian officer who endured considerable combat, wounding and imprisonment, as well as one of the more infamous episodes of the Civil War, only to die, shortly after the cessation of hostilities. The letter remains in excellent condition; it was written on period, lined paper, from Pt. Lookout. The collector from whom we obtained the letter had it archivally framed.

Measurements: Frame size – H – 9.5″ W- 6.25″; Letter size – H – 8″ W – 5″

| Residence Duplin County NC;

Enlisted on 4/2/1862 as a 1st Sergeant. On 4/2/1862 he was commissioned into “A” Co. NC 43rd Infantry He died of disease on 7/3/1865 at Hilton Head, SC He was listed as: * Wounded 7/3/1863 Gettysburg, PA * Hospitalized 7/4/1863 Frederick, MD (Estimated day) * POW 7/4/1863 Gettysburg, PA (Estimated day) * Confined 7/10/1863 Fort Delaware, DE * Transferred 7/20/1863 Johnson’s Island, OH * Transferred 2/9/1864 Point Lookout, MD * Transferred 6/23/1864 Fort Delaware, DE * Transferred 8/20/1864 Hilton Head, SC Promotions: * 2nd Lieut 3/6/1862 * 1st Lieut 3/20/1862 He also had service in: “1st C” Co. NC 12th Infantry

List of the Immortal 600 Captured at Gettysburg

|

| CARR, 1Lt. Robert B. |

| Co. A, 43rd North Carolina Infantry |

| res. Maynolin or Magnolia, North Carolina; captured at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on 3-5, 1863; d. 3 Jul 1865 at Hilton Head, South Carolina, of chronic diarrhea. |

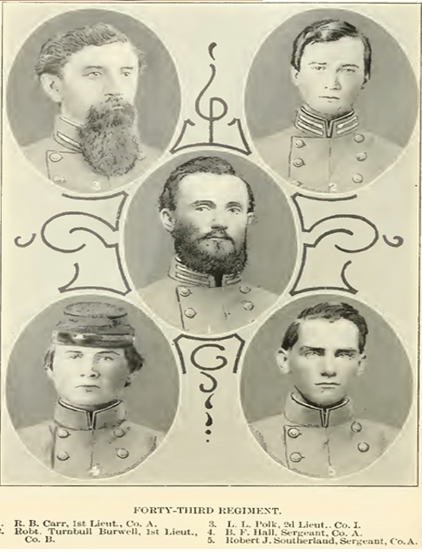

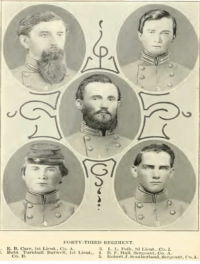

43rd NC Infantry

| Organized: on 4/24/62 Mustered Out: 4/9/65 |

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comment |

| Jun ’62 | Sep ’62 | Daniel’s | Dept of North Carolina | |||

| Sep ’62 | Dec ’62 | Daniel’s | Dept of North Carolina and South Virginia | |||

| Dec ’62 | Dec ’62 | Daniel’s | Elzey’s | Dept of North Carolina and South Virginia | ||

| Dec ’62 | Feb ’63 | Daniel’s | French’s | Dept of North Carolina and South Virginia | ||

| Feb ’63 | Apr ’63 | Daniel’s | D.H. Hill’s | Dept of North Carolina and South Virginia | ||

| Apr ’63 | May ’63 | Daniel’s | Dept of North Carolina | |||

| May ’63 | Jun ’64 | Daniel’s/Grimes’ | D.H. Hill’s/Rodes’ | 2nd | Army of Northern Virginia | |

| Jun ’64 | Dec ’64 | Grimes’ | Rodes’/Grimes’ | Valley Dist | Dept of Northern Virginia | |

| Dec ’64 | Apr ’65 | Grimes’ | Grimes’ | 2nd | Army of Northern Virginia |

This regiment was organized at Camp Mangum, about three (3) miles west of Raleigh, on March 18, 1862, by electing Junius Daniel, Colonel; Thomas S. Kenan (Captain Company A, formerly Captain Company C, 2nd NC Volunteers), Lieutenant Colonel; and Walter J. Boggan (Captain Company H), Major, commissions bearing date 25 March, 1862. Daniel was at the time Colonel of the 14th NC Regiment, and soon thereafter was also chosen Colonel of the 45th NC Regiment, and accepted. Upon his reporting for duty he was placed in command of a brigade, of which the 43rd NC Regiment afterwards formed a part. Junius Daniel was subsequently promoted to Brigadier General. About April 20th, Thomas S. Kenan was notified that he had been chosen Colonel of the 38th NC Regiment upon its re-organization at Goldsborough, the information being officially conveyed by the hands of 3rd Lt. David M. Pearsall, of the 38th NC Regiment; but he remained with the 43rd NC Regiment and was elected its Colonel a few days thereafter (April 21st), and William Gaston Lewis (Major of the 33rd NC Regiment) was elected Lieutenant Colonel, commission bearing date April 25, 1862.

The staff and company officers, and their successors by promotion from time to time in the order named, as appears from the “Roster of North Carolina Troops, Volume 3,” pp. 196-225, and gathered from memoranda of participants in the operations of the regiment, were:

Adjutants—Drury Lacy, Jr., William R. Kenan.

Surgeons—Bedford Brown, Jr., William T. Brewer

Assistant Surgeon—Joel B. Lewis.

Quartermasters—John W. Hinson, Joseph B. Stafford.

Commissary—William B. Williams.

Chaplains—Joseph W. Murphy, Eugene W. Thompson.

Sergeant Majors—William T. Smith, Hezekiah Brown, Thomas H. Williams, Robert T. Burwell (?), William R. Kenan.

CAPTAINS:

Company A—From Duplin—James G. Kenan (succeeded Thomas S. Kenan); number of enlisted men, 117. The company entered the service in April, 1861, and was Company C, 2nd NC Volunteers (Col. Solomon Williams), stationed near Norfolk, VA. Upon the expiration of its six-months term of service it was re-organized and assigned to the 43rd NC Regiment. Captain Kenan, of this company, was wounded and captured at Gettysburg, and was a prisoner when the war ended, and many of the officers, hereinafter named, met a similar fate, or were killed or disabled there or in subsequent engagements, but a correct list of casualties cannot now be had—and they were so numerous that during the latter part of the war the regiment was commanded by Captains, and companies by Lieutenants, Sergeants, and Corporals.

Company B—From Mecklenburg—Robert P. Waring, William E. Stitt. Enlisted men, 73.

Company C—From Wilson—James S. Woodard, Ruffin Barnes. Enlisted men, 102.

Company D—From Halifax and Cumberland—Cary W. Whitaker. Enlisted men, 93.

Company E—From Edgecombe—John A. Vines, James R. Thigpen, Wiley J. Cobb. Enlisted men, 96.

Company F—From Halifax—William R. Williams, William C. Ousby, Henry A. Macon, James H. Morris. Enlisted men, 101.

Company G—From Warren—William A. Dowtin, Levi P. Coleman, Alfred W. Bridgers. Enlisted men, 110.

Company H—From Anson—John H. Coppedge (succeeded Walter J. Boggan), Hampton Beverly. Enlisted men, 112.

Company I—From Anson—Robert T. Hall. Enlisted men, 139.

Company K—From Anson—James Boggan, Caswell H. Sturdivant. Enlisted men, 120.

FIRST LIEUTENANTS:

Company A, James G. Kenan, Robert B. Carr.

Company B, Henry Ringstaff.

Company C, Henry King, Ruffin Barnes, L. D. Killett.

Company D, Thomas W. Baker, John S. Whitaker.

Company E, James R. Thigpen, Wiley J. Cobb, Charles Vines.

Company F, William C. Ousby, Henry A. Macon, James H. Morris, Jesse A. Macon.

Company G, Levi P. Coleman, Alfred W. Bridgers.

Company H, John H. Coppedge, Hampton Beverly, Benjamin F. Moore.

Company I, Richard H. Battle, Jr., John H. Threadgill.

Company K, Caswell H. Sturdivant, Henry E. Shepherd.

SECOND & THIRD LIEUTENANTS:

Company A, Robert B. Carr, John W. Hinson, Thomas J. Bostic, Stephen D. Farrior.

Company B, William E. Stitt, Julius J. Alexander, Robert T. Burwell.

Company C, William T. Brewer, Ruffin Barnes, L. D. Killett, Bennett Barnes, Hezekiah Brown.

Company D, Thomas W. Baker, John S. Whitaker, William Beavans, George W. Wills.

Company E, Wiley J. Cobb, Van B. Sharpe, John H. Leigh, Charles Vines, Willis R. Dupree, Thomas H. Williams.

Company F, Henry A. Macon, William R. Bond, James H. Morris, William L. M. Perkins, Jesse A. Macon.

Company G, Alfred W. Bridgers, William B. Williams, Alexander L. Steed, John B. Powell, Luther R. Crocker.

Company H, Hampton Beverly, Benjamin F. Moore, William W. Boggan, Henry C. Beaman, Peter B. Lilly.

Company I, John H. Threadgill, John Ballard, Stephen W. Ellerbe, Leonidas L. Polk.

Company K, John A. Boggan, Henry E. Shepherd, Stephen Huntley, Francis J. Flake.

The regiment was ordered to Wilmington and Fort Johnston at Smithville (now Southport), on the Cape Fear River, where it remained about a month in Brig. Gen. Samuel G. French’s (MS) command, and thence to Virginia. Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel’s (NC) Brigade, composed of the 32nd, 43rd, 45th, 50th, and 53rd NC Regiments, was placed in the command of Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes (NC), and on the last of the Seven Days’ Battles around Richmond was ordered to occupy the road near the James River, where it was subjected to a fierce shelling from the gunboats on the right and the batteries on Malvern Hill in front, but was not in the regular engagement; was afterwards ordered to Drewry’s Bluff, and constituted part of the forces under Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith (VA) for the protection of Richmond and vicinity during the advance of the army under General Robert E. Lee into Maryland in September of 1862; and about the same time a demonstration was made against Suffolk, VA, by troops under Brig. Gen. French (this regiment being a portion of them), probably for the purpose of preventing the Federals from sending reinforcements from that territory to oppose the movement of the Confederates in Maryland.

They returned in about ten (10) days, and the regiment resumed its position at Drewry’s Bluff, where it was engaged in drilling and putting up breastworks under the direction of Lt. Col. William G. Lewis, who, being a civil engineer by profession, was ordered by the brigade commander to supervise their construction. Shortly after quarters were prepared for the winter, the brigade was ordered to Goldsborough, in December of 1862, to reinforce the Confederates in opposing the advance of the Union troops from New Bern under Federal Maj. Gen. John G. Foster; but on the day before its arrival they succeeded in burning the railroad bridge over the Neuse River, and, after a sharp engagement with the Confederates on the south side of the river, retreated to their base of operations at New Bern. The bridge was immediately rebuilt on trestles by a detail of men from the brigade, our Lt. Col. Lewis superintending the work

During the Spring of 1863 it was stationed at Kinston and detachments sent out to prevent the approach of the enemy into the interior. Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill (NC) having assumed conunand of the department, directed demonstrations to be made in aid of military operations at other points and to compel the enemy to abandon their outposts. In the affair at Deep Gully (aka Fort Anderson), a small creek, upon the eastern bank of which the enemy were entrenched, the 43rd NC Regiment was ordered to attack, and after a few rounds the enemy abandoned the works and retreated. The brigade was then ordered to Washington, NC, and was there subjected to the artillery fire of the Union forces occupying that place, but, with the exception of some skirmishing, no engagement was brought on. It then returned to its former quarters at Kinston, and, later on, went to Fredericksburg, VA, and was assigned to Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’ (AL) Division of the Second Corps (Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s), the 32nd, 43rd, 45th, and 53rd NC Regiments and the 2nd NC Battalion then constituting the brigade—the 50th NC Regiment having been assign

ON THE MARCH

Upon arriving at Brandy Station the brigade was placed in line of battle to meet any attempted advance of Union infantry to support its cavalry, but was not engaged—the main fighting in that terrific battle (June 9th) being between the cavalry of the opposing armies. At Berryville the enemy were driven by the cavalry, supported by this brigade, and camp equipage, etc., captured. It then marched by way of Martinsburg, Williamsport, Hagerstown and Chambersburg to Carlisle, PA, and occupied the barracks at that place, from which it was ordered to Gettysburg.

IN THE THREE DAYS’ FIGHT

Upon arriving at Gettysburg, on Wednesday, July 1, 1863, about 1 o’clock p.m., a line of battle was formed near Forney’s House, northwest of the town and to the left of Maj. Gen. William D. Pender’s (NC) Division of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s (VA) Corps, which had repulsed the enemy in the forenoon, and the troops advanced to the attack. The fight was continued till late in the afternoon and the enemy driven back, the brigade being handled with consummate skill by our brave Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel (NC). Seminary Ridge was gained and occupied—the right of the 43rd NC Regiment resting on the railroad cut. The fight was terrific and the loss heavy on both sides. On Thursday morning, July 2nd, the regiments were assigned to various positions upon the line. The 43rd NC Regiment supported a battery, during the artillery duel which continued nearly the whole day, at a point on the ridge just north of the Seminary building, and the shot and shell from the guns of the enemy on Cemetery Heights caused serious loss. It was during this cannonade that General Robert E. Lee and his staff passed to the front along the road near by, and the troops saluted him by raising their hats in silence, and were encouraged by his presence. From this point a movement was commenced at night in line of battle, in the direction of the enemy’s works, the skirmishers firing upon the Confederates and retreating, but inflicting no loss.

The moon was shining brightly, and it seemed that a night attack upon Cemetery Heights was contemplated; but when the brigade crossed the valley in front, orders were given to march by the left flank near the southern and eastern limits of the town, and about daybreak on Friday, July 3rd, it reported to Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson (GA), who commanded the Division of Ewell’s Corps on the extreme left of the Confederate line. Brig. Gen. Daniel’s Brigade, with other troops, had been ordered to reinforce Maj. Gen. Johnson’s position on Culp’s Hill. It marched nearly all night, and formed a line of battle near Benner’s House, crossed Rock Creek, and, through the undergrowth, among large boulders and up the heavily timbered hill, the attack upon the enemy was made, the line of works (formed by felled trees) taken, but the charge upon the main line was repulsed. Col. Thomas S. Kenan, of the 43rd NC Regiment, was wounded in leading this charge, and taken from the field (captured on the retreat and imprisoned until the close of the war), and the command devolved on Lt. Col. William G. Lewis.

The forces under Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson (GA) held their positions until night, when they were withdrawn—the 43rd NC Regiment occupying its first position on Seminary Ridge until the army moved to Hagerstown. On the retreat it was assigned the rear position, and in consequence was repeatedly engaged with the Union advance. After remaining at Hagerstown a few days the Confederates crossed the swollen Potomac River (carrying their guns and their ammunition on their heads, the water being up to their armpits), and fell back to the village of Darksville. Later, they were in front of the Federal army, on the south bank of the Rapidan River, guarding the fords, and engaged the enemy at Mine Run when an advance towards Richmond was made. After the retreat of the Federals to the north of the Rapidan River, and active operations having comparatively ceased, winter quarters were built, but they were not long occupied by this regiment, for it was detached for duty with Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s (NC) Brigade in the winter campaign in 1863-’64 in Eastern North Carolina, Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett (VA) being in command of all the forces.

In this campaign Brig. Gen. Hoke’s Brigade consisted of the 6th, 21st, 54th and 57th NC Regiments and the 1st NC Battalion, and attached to it were the 43rd NC Regiment and 21st GA Regiment. In approaching New Bern this regiment arrived at Bachelor’s Creek, about seven (7) miles from the city, and made a night attack upon the enemy’s works, but, discovering that the flooring of a bridge across the creek, about seventy-five (75) feet long, had been removed Lt. Col. William G. Lewis informed Brig. Gen. Robert F Hoke (NC) that if he would send him plank from the pontoon train he would renew the attack as soon as practicable. Brig. Gen. Hoke complied, and the attack was made at daylight the next day—one of the companies laying the plank, under fire, and the others crossing over, also under fire, driving the enemy and causing a retreat to New Bern.

There were also some Union troops at Clark’s brickyard, on the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad, nine (9) miles above the city, and information was received that a train of cars had been sent from New Bern to bring them in. The regiment was ordered to capture this train, without wrecking it, if possible, and accordingly a three-mile march at quick and double-quick time was made to intercept it. When the regiment got within about twenty or thirty (20-30) yards of the track the train was passing at its highest speed, and shots were exchanged between the opposing parties. If success had attended this movement, the purpose of Brig. Gen. Hoke was to place his troops on the train, run into the town and surprise the garrison. Maj. Gen. Pickett’s expedition, however, was not successful, and the troops fell back to Kinston, remaining there a few weeks, and then marched on to Plymouth.

43rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment

Confederate Regiments & Batteries * North Carolina

| 1862 | |

| March | The 43rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment was organized near Raleigh at Camp Mangum.

Company A – “The Duplin Rifles” – Duplin County – Captain James G. Kenan. |

| April 24 | Colonel Thomas Kenan, Lieutenant Colonel William G. Lewis and Major Walter G. Boggan were mustered in as field officers. |

| May | Captain John A. Vines of Company E resigned, and First Lieutenant James R. Thigpen was promoted to take his place. Captain James Boggan of Company K resigned, and First Lieutenant Caswell H. Sturdivant was promoted to take his place. |

| June-September | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, Department of North Carolina. |

| June 25-July 1 |

Seven Days Battles |

| June 30 |

Malvern Cliff |

| August | Captain W.A. Dowtin of Company G died, and First Lieutenant Levi P. Coleman was promoted to replace him. Captain John H. Coppedge of Company G resigned, and First Lieutenant Beverly was promoted to replace him. |

| September-December | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. |

| December | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, Elzey’s Command, Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. |

| December-February | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, French’s Command, Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. |

| 1863 | |

| January | Captain James L. Woodard of Company C resigned and First Lieutenant Ruffin Barnes was promoted to take his place. Captain James R. Thigpen of Company E resigned and First Lieutenant Wiley J. Cobb was promoted to take his place. |

| February-April | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, D.H. Hill’s Command, Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. |

| April-May | Assigned to Daniel’s Brigade, Department of North Carolina. |

| May | Assigned to Daniel’s-Grimes’ Brigade, Rodes’ Division, 2nd Corps, Army of Northern Virginia. |

| May 11 | Captain William R Williams of Company F resigned and First Lieutenant William C. Ousby was promoted to replace him. |

| June 14 |

Martinsburg |

| July 1-4 |

Battle of GettysburgThe regiment was commanded at Gettysburg by Colonel Thomas S. Kenan. He was wounded in the attack on Culp’s Hill on July 3, and Lieutenant Colonel William Lewis took command. Colonel Kenan was captured during the retreat to Virginia and confined at Johnson’s Island, Ohio. He was not exchanged until just before the end of the war. The regiment brought 572 men to the field and lost 26% casualties. It attacked the Federal line on Seminary Ridge on July 1, supported a battery on the ridge on July 2, and on July 3 took position on the exreme left of the Confederate line for the assault on Culp’s Hill. First Lieutenant William C. Ousby of Company F was killed. Lieutenants Julius Alexander of Company B, Thomas Baker of Compay D and William W. Boggin of Company H were mortally wounded. Captain James Kennan of Company A and First Lieutenants Robert R. Carr of Company A, Drury Ringstaff of Company B and Henry E. Sheperd of Company K were wounded and captured. First Lieutenant Benjamin F. Moore of Company H, Second Lieutenant Jesse A. Macon of Company E and Second Lieutenants William Eason and Leonidas L. Polk of Company I and Second Lieutenant Francis E. Flake of Company K were wounded. First lieutenant Henry A. Macon was promoted to captain of Company F. |

Carr, Robert B. (1st Lieutenant): Present 30 June, he suffered a shrapnel wound to the left foot about 11 am 3 July and was captured. Admitted to the general hospital at Frederick, MD, 6 July, he was transferred to Annapolis, MD, the following day and was a member of the “immortal 600,”a group of Confederate officers used as human shields by the Federals during the bombardment of Charleston, SC, in 1864. He died of chronic diarrhea at Hilton Head, SC, 3 July 1865. Standing 6’0”this 34-year-old farmer from Duplin County enlisted as the 1st Lieutenant of Company A, on 2 April 1862 and took the Oath of Allegiance to his state. (From: Confederate Casualties at Gettysburg by John W. Busey and Travis W. Busey)

From the monument at Gettysburg to the 43rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment on East Confederate Avenue:

Forty-third

North Carolina Regiment

Daniel’s Brigade Rodes’s Division

Ewell’s Corps

Army of Northern Virginia

Thomas Stephen Kenan

Colonel

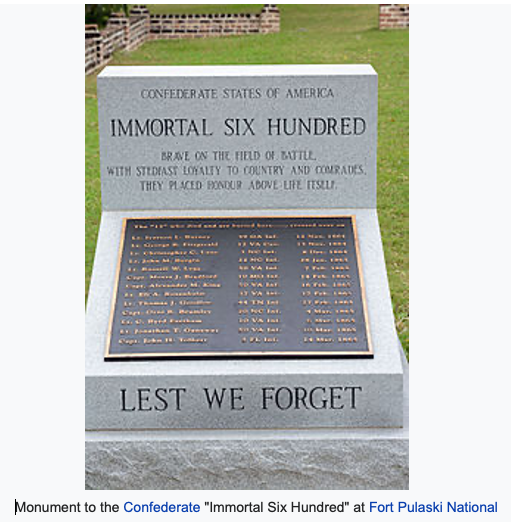

The Immortal Six Hundred

The Immortal Six Hundred were 600 Confederate officers who were held prisoner by the Union Army in 1864–65. In the summer of 1863, the Confederacy passed a resolution stating all captured African-American soldiers and the officers of colored troops would not be returned. The resolution also allowed for any captured officer of colored troops to be executed and any captured African-American soldier be sold into slavery. The resolution caused a breakdown in the exchange of captured soldiers as the Union demanded all soldiers be treated equally. The Immortal Six Hundred were one group of officers who could not be exchanged.

In June 1864, the Confederate Army imprisoned five generals and forty-five Union Army officers in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, using them as human shields in an attempt to stop Union artillery from firing on the city.[2] In retaliation, United States Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered fifty captured Confederate officers, of similar ranks, to be taken to Morris Island, South Carolina, at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. The Confederates were landed on Morris Island late in July of that year.

The Confederates had originally contended that Charleston should not be shelled. The correspondence between Major General John G. Foster, commanding the Federal Department of the South, and Major General Samuel Jones, commanding the Confederate Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, indicates the Confederates subsequently accepted the military nature of Charleston as a target. Soon the correspondence turned to an exchange of these high-ranking prisoners.

Instructions from the War Department reached Foster in late July, and he coordinated an exchange of the fifty prisoners on July 29. Exchange of the fifty officers actually took place on August 4, 1864. However, at that time Jones brought 600 additional prisoners to Charleston, in part to press for a larger prisoner exchange. In retaliation for the treatment of Federal prisoners, Foster asked for a like number of Confederate prisoners to be placed on Morris Island. These men became known in the South as the Immortal Six Hundred.

At one point General Foster planned an exchange of the six hundred, but General Ulysses S. Grant refused, following Order 252 which stated no exchanges would occur until the Confederacy agreed to treat both black and white prisoners of war equally. Grant wrote, “In no circumstances will he be allowed to make exchanges of prisoners of war.”

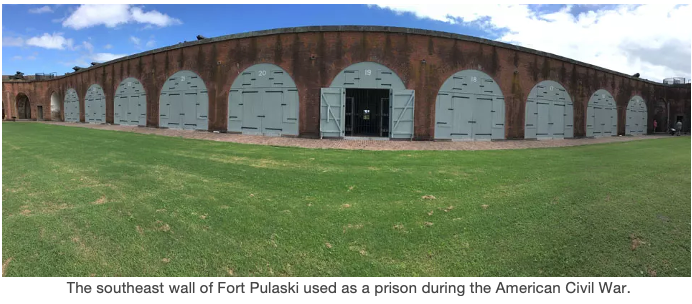

The Confederate prisoners did not arrive on Morris Island until the first week of September 1864. During the first week of October 1864, Jones (under orders from Lieutenant General William J. Hardee) removed the Federal prisoners from Charleston. Foster removed the Confederate prisoners from Morris Island only after being informed officially of the Federal prisoners’ status. At that time the Immortal 600 were moved to Fort Pulaski.

Three of the six hundred died from subsistence on starvation rations issued as retaliation for the conditions found by the Union at the Confederate prisons in Andersonville in Georgia and at Salisbury Prison in North Carolina.

Upon an outbreak of yellow fever in Charleston, the Union officers were removed from the city limits. In response the Union Army transferred the Immortal Six Hundred to Fort Pulaski outside of Savannah.

There they were crowded into the fort’s casemates. For 42 days, a “retaliation ration” of 10 ounces (280 g) of moldy cornmeal and 1⁄2 US pint (0.24 l; 0.42 imp pt) of soured onion pickles was the only food issued to the prisoners. The starving men were reduced to supplementing their rations with the occasional rat or stray cat. Thirteen men died there of diseases such as dysentery and scurvy.

At Fort Pulaski, the prisoners organized “The Relief Association of Fort Pulaski for Aid and Relief of the Sick and Less Fortunate Prisoners” on December 13, 1864. Col. Abram Fulkerson of the 63rd Tennessee Infantry Regiment was elected president. Out of their sparse funds, the prisoners collected and expended eleven dollars, according to a report filed by Fulkerson on December 28, 1864.

Five more of the Immortal Six Hundred later died at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. The remaining prisoners were returned to Fort Delaware on March 12, 1865, where another twenty-five died.

A notable escape effort was led by Captain Henry Dickinson of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. On the prisoner’s journey to Fort Delaware, Dickinson organized a group of thirteen officers, including Colonel Paul F. DeGournay of the 12th Battalion, Louisiana Artillery and Colonel George Woolfolk, to try to escape from the gunboat. However, the effort failed when the captain of the ship, noticing that one of the 13 men was missing, led the prisoners to the brig below the deck of the ship.

The prisoners became known throughout the South for their refusal to take the Oath of Allegiance under duress. Southerner apologists and those who believe in the Lost Cause have long lauded their refusal as honorable and principled.

In October 1864, Union troops stationed at Fort Pulaski accepted transfer of a group of imprisoned Confederate officers who later became known as The Immortal Six Hundred.

Before arriving at Fort Pulaksi, the prisoners were being held in South Carolina. Edwin M. Stanton, Federal Secretary of War, ordered that 600 prisoners of war be positioned on Morris Island in Charleston harbor within direct line of fire from Confederate guns at Fort Sumter. Stanton’s order was a response that followed word that 600 Union officers imprisoned in the city of Charleston were exposed to direct line of fire from Federal artillery.

This standoff continued until a yellow fever epidemic forced Confederate Major General S. Jones to remove the Federal prisoners from the city limits. The Confederate prisoners were then transferred the from the open stockade at Morris Island to Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River.

On October 23,1864, over 500 tired, ill-clothed, men arrived at Cockspur Island. Early on the emaciated troops received extra rations and were promised extra blankets and clothing. However, despite the best intentions of the fort’s command, the prisoners never received sufficent food, blankets or clothes.

“After picking out the lumps, bugs, and worms in this rotten corn meal there was not more than seven ounces of meal left fit for use. About December 10th scurvy made its appearance in our prison amongst the weakest of the prisoners. Most every man in the prison was suffering more or less with dysentery and a large majority were from the starvation diet, unable to leave their bunks.” Capt. J. Ogden Murray; VA. 7th Cav. Staff

“Two days ago, Lt. George B. Fitzgerald was taken to the hospital, and this morning announcement was made that “Fitz is dead”. He was a confirmed opium eater; a poor, miserable wreck–ragged, filthy, lousy…He has had no blanket, no socks, hardly clothes to cover him; none of us could supply him, and he slept alone, covering himself with an old piece of tent fly…A graduate of West Point; a lieutenant in the old army, mingling with the Lees, McClellands and Grants…” Capt. Henry Dickinson; 2nd VA. Cav.

During the Immortal Six Hundred’s incarceration at Fort Pulaski, thirteen prisoners died. The dead were buried on site at Cockspur Island. Most died of dehydration due to dysentery. In March of 1865, the remainder of the prisoners were transferred to Fort Delaware located 15 miles south of Wilmington, DE.