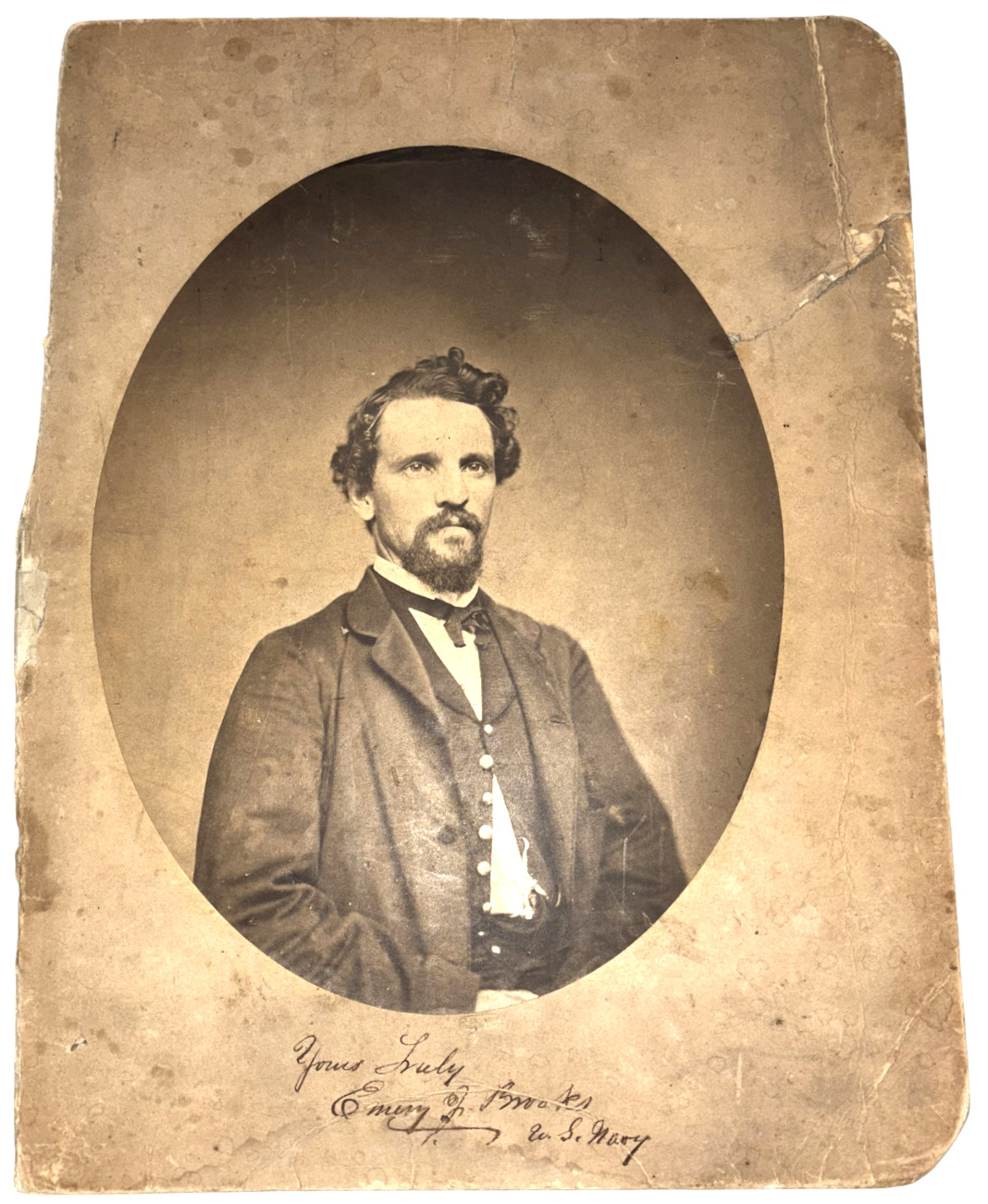

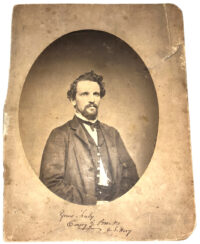

Large Id’d Albumen of a Civil War Navy Engineer on the Steam Sloop USS Richmond -Emo(e)ry J. Brooks – Image by Famed Phila. Photographer Frederick Gutekunst – Image Dated 1862

SOLD

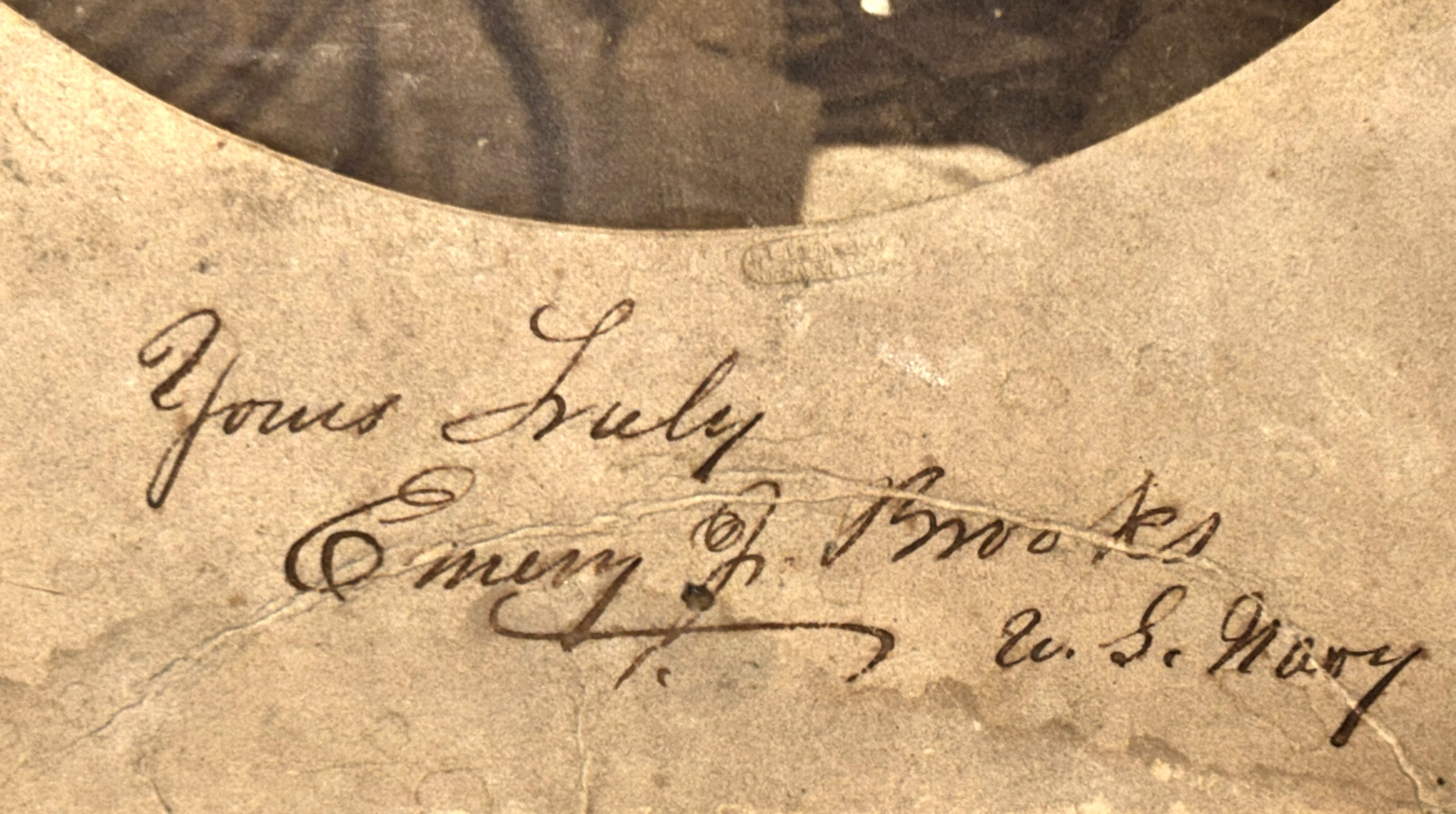

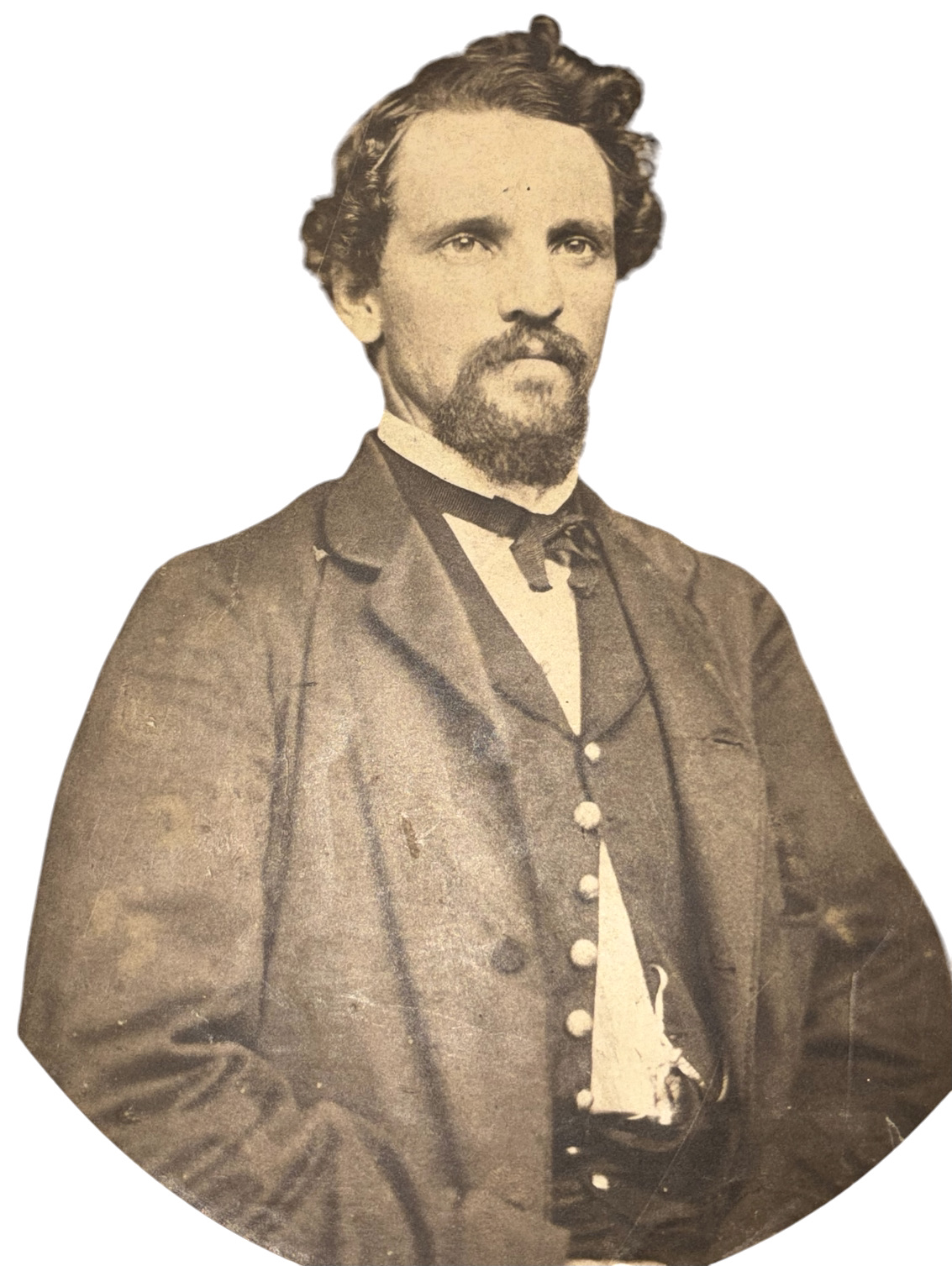

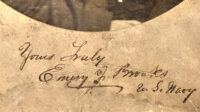

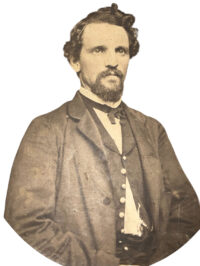

Large Id’d Albumen of a Civil War Navy Engineer on the Steam Sloop USS Richmond -Emo(e)ry J. Brooks – Image by Famed Phila. Photographer Frederick Gutekunst – Image Dated 1862 – This albumen is a somewhat rare large size image, attached to period card stock; the image depicts Emory or Emery J. Brooks, dressed in his plain pilot’s jacket with a navy vest beneath; tucked in Brooks’ vest appears to possibly be a bosun’s pipe with a lanyard attached. Below the image is handwritten, by Brooks, the following:

“Yours Truly

Emery J. Brooks

U.S. Navy”

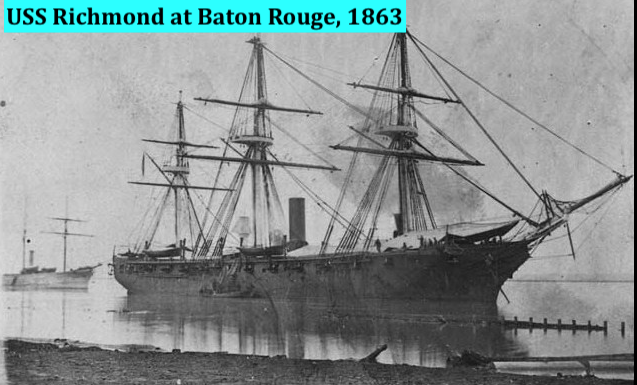

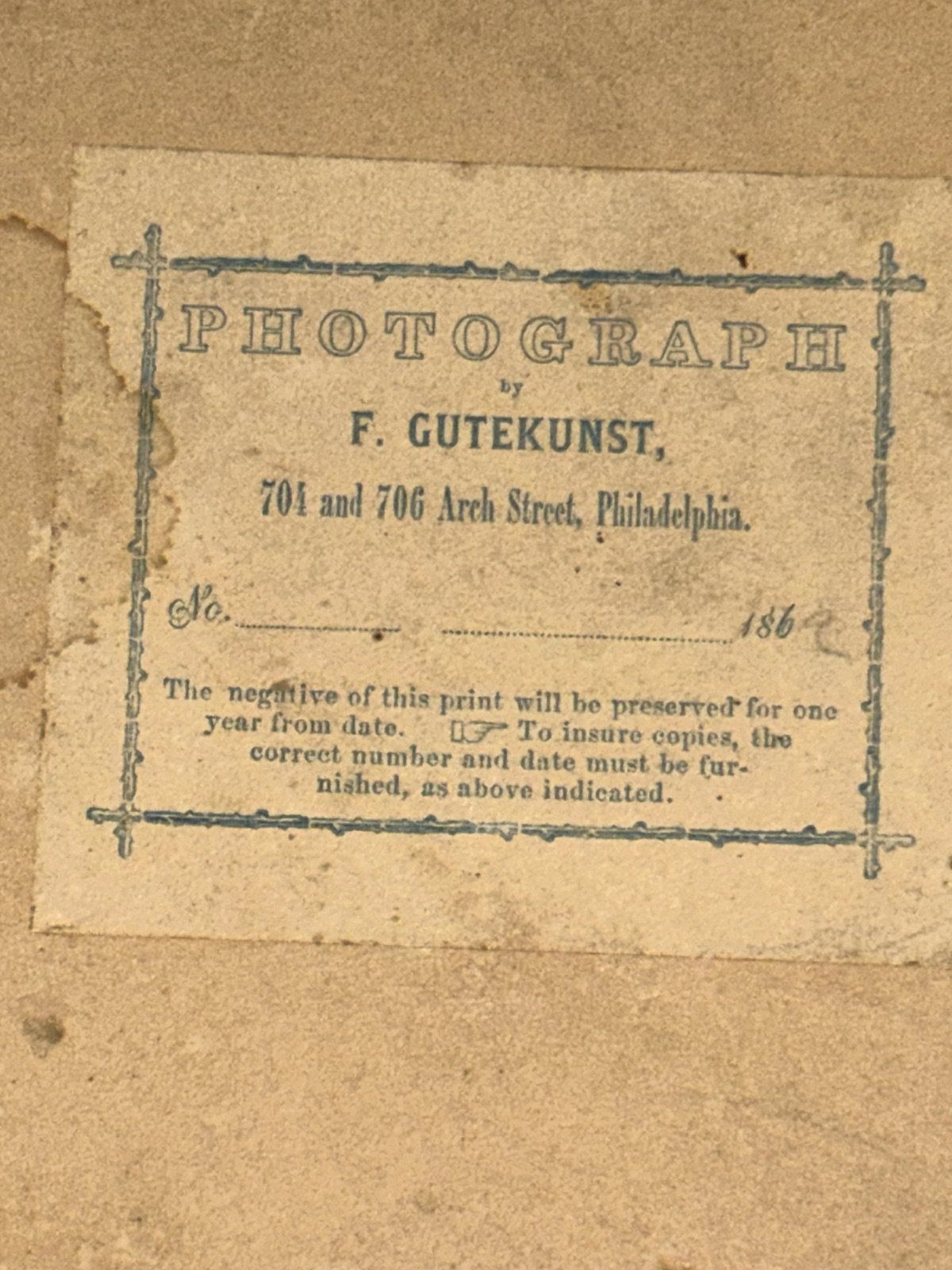

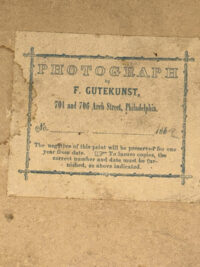

On the back of the image is the label for the photographer – Frederick Gutekunst, with his Philadelphia wartime address enumerated; below Gutekunst’s address is a space for the number of the print, which is blank, but beside this blank space is printed “1862” – the “2” is written in pencil. Brooks’ first name is listed as “Emory J. Brooks” in the U.S. Navy records of the period; he enlisted in the USN in May 1859 as a Third Assistant Engineer and was gradually promoted to the rank of First Assistant Engineer by May 1863; he remained in the navy until he resigned in December 1868. His wartime service was aboard the sloop steamer USS Richmond. The Richmond, named after the capital of Virginia, was launched in the Norfolk Navy Yard in October 1860. This vessel would see considerable service during the war. Richmond, commanded by Capt. D. N. Ingraham, departed Norfolk 13 October 1860 for the Mediterranean. Upon her return to New York 3 July 1861, the nation had already been plunged into the Civil War so she was immediately readied for sea. The Richmond had a complement of 259 men aboard and was armed with: 1 80-pounder Dahlgren smooth bore, 20 9- Dahlgren smooth bores, and a 30-pounder Parrott rifle. After cruising before Fort Pickens, Richmond was ordered to the Head of the Passes at the mouth of the Mississippi River where she patrolled the river’s mouth to maintain the blockade. Richmond’s captain became commander of a small flotilla, which included the sloop of war, Preble, and the dispatch vessel, Water Witch. Richmond then cruised off the mouth of the river, blockading Confederate forces and aiding Army engineers erecting batteries on the banks of the South and Southwest passages. Farragut’s squadron, with Richmond in company, successfully passed Vicksburg, exchanging heavy fire on 28 June 1862 and was present when Farragut’s fleet joined with Commodore Davis’ Western Flotilla above Vicksburg on 1 July 1862; during this engagement, Richmond suffered two killed and was damaged almost as severely as during the New Orleans campaign. The ship would sustain heavy damage during the various campaigns in the Mississippi. The Richmond, after much needed repairs, would continue to remain in action with Admiral Farragut’s fleet, to include significant participation in the assaults on Mobile Bay. A more detailed overview of the Richmond’s wartime activities can be read below.

This image remains in overall good condition, as does Gutenkunst’s label on the back – slight water-staining is present. The card stock has a tear on one side, but this does not impact the image. Id’d, Civil War navy personnel images are difficult to find.

Measurements: Cardstock backing – H – 15.5”; W – 12”

Image – H – 12”; W – 9”

Brooks, Emory J.

Third Assistant Engineer, 3 May, 1859. Second Assistant Engineer, 3 October, 1861. First Assistant Engineer, 20 May, 1863. Resigned 7 December, 1868.

| Name: | Emory J Brooks |

| Rank Information: | Third Assistant Engineer, Second Assistant Engineer, First Assistant Engineer, Resigned |

| First Service Date: | 3 May 1859 |

| Other Service Dates: | 3 Oct 1861, 20 May 1863 |

| Name: | Emery J Brooks | ||||||||||

| Rank: | 3d Assistant Engineer | ||||||||||

| Military Year: | 1859

|

| Name: | Emery J Brooks |

| Rank: | Lieutenant |

| Military Year: | 1866-1868 |

| Military Country: | USA |

| Ship or Station: | Special Duty Boston |

Richmond (Steam Sloop)

(Steam Sloop: displacement 2,604; length 225-; beam 42-6-; draft 17-4– (mean); complement 259; armament 1 80-pounder Dahlgren smooth bore, 20 9- Dahlgren smooth bore, [1] 30-pounder Parrott rifle) Named after he capital of the state of Virginia.

The second Richmond, a wooden steam sloop of war, was launched on 26 January 1860 by the Norfolk Navy Yard; sponsored by a Miss Robb. Richmond, commanded by Capt. D. N. Ingraham, departed Norfolk 13 October 1860 for the Mediterranean. Upon her return to New York 3 July 1861, the nation had already been plunged into civil war so she was immediately readied for sea. Her first war service began 31 July 1861 when she sailed for Kingston, Jamaica, to search for the elusive Confederate raider Sumter commanded by Raphael Semmes. Leaving Trinidad on 5 September, Richmond cruised along the southern coast of Cuba and around Cape San Antonio. Semmes, however, reached New Orleans; and, by 22 August, Richmond was at Kingston taking on coal again. Departing 25 August, Richmond arrived at Key West on 2 September en route north to join the Gulf Blockading Squadron.

After cruising before Fort Pickens, Richmond was ordered to the Head of the Passes at the mouth of the Mississippi River where she patrolled the river’s mouth to maintain the blockade. Richmond’s captain became commander of a small flotilla, which included the sloop of war, Preble, and the dispatch vessel, Water Witch. The ships were taken across the bar at the Head of the Passes during the first week of October.

In the early morning darkness of the 12th, the Confederate ram Manassas and three armed steamers attacked the Richmond and her consorts in an attempt to break the blockade and to prevent Union control of land approaches in the Head of the Passes area. Steaming under cover of darkness, the Confederate ships took the Union squadron by surprise. Richmond was taking on coal from the schooner, Joseph N. Toone, when the Manassas rammed Richmond tearing a hole in the sloop’s side. Passing aft, the ram tried but failed to hit Richmond again before disappearing astern. Richmond’s gunners got away one complete broadside from the port battery though, somewhat evening the score.

While Vincennes and Preble retired down the southwest Pass, Richmond covered their retreat. Three Confederate fire rafts were then sighted floating down river, and several large steamers were seen astern of them. In attempting to cross the bar, both Vincennes and Richmond grounded and were taken under fire by Confederate gunners afloat and ashore. Fortunately, the Army transport, McClellan, arrived with long range rifled guns on loan from Fort Pickens; and halted the second Confederate attack.

Richmond then cruised off the mouth of the river, blockading Confederate forces and aiding Army engineers erecting batteries on the banks of the South and Southwest passages. In mid-November 1861, she returned to Pensacola Bay for temporary repairs. On 22 November Richmond joined the steam sloop of war Niagara and the guns of Fort Pickens to bombard Pensacola Navy Yard, the Confederate defenses at Fort McRae, and the town of Warrington. On the second day of firing Richmond had one man killed and seven wounded when hit twice by shore fire. One shell hit forward, destroying railing and hammock nettings, and one aft on the starboard side glanced under her counter, exploding 4 feet underwater, damaging her bottom and causing serious leaks. Richmond retired to Key West, and stood out from that port 27 November 1861 for repairs at the New York Navy Yard.

Richmond departed New York on 13 February 1862. Richmond joined the West Gulf Blockading Squadron off Ship Island on 5 March as Flag Officer Farragut prepared to seize New Orleans. Richmond crossed the bar on 24 March with the fleet and began making preparations for battle.

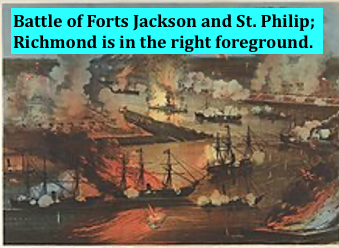

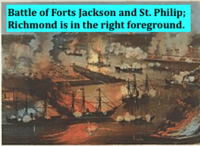

On 16 April, Farragut’s fleet moved to a position below Forts Jackson and St. Philip. Mounting over 100 guns, these forts were the principal shore defenses of New Orleans. The Confederates had also gathered a flotilla of requisitioned gunboats and were trying to complete the powerful casemate ram Louisiana as well. They further counted on using fire ships to disrupt the large Union squadron.

Hidden by intervening woods, the Union mortar flotilla under Comdr. David D. Porter began a 6-day bombardment of the Confederate forts on 18 April 1862. The Confederates began sending fire rafts downstream, and Richmond reported dodging one in the early morning of 21 April which “passed between us and the Hartford, the great flames shooting as high as the masts.” On 24 April Farragut’s fleet ran past the forts, engaged and defeated the Confederate flotilla, and continued upriver for about 12 miles. Though Richmond was hit 17 times above the waterline, her chain armor kept out many rounds and limited her casualties to two killed and three wounded. Richmond landed her Marine detachment at New Orleans to help keep order until General Butler’s Army troops arrived.

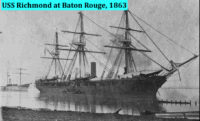

Richmond helped take possession of military installations at Baton Rouge on 10 May 1862. Four days later she cruised upriver, first to a point 12 miles below the juncture of the Red River, thence off Natchez and finally to a position below the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg on 18 June 1862.

Farragut’s squadron, with Richmond in company, successfully passed Vicksburg exchanging heavy fire on 28 June 1862 and was present when Farragut’s fleet joined with Commodore Davis’ Western Flotilla above Vicksburg on 1 July 1862. Richmond again suffered two killed and was damaged almost as severely as during the New Orleans campaign. On 15 July 1862 the Confederate casemate ram Arkansas came out of the Yazoo River and ran past the Union Fleet above Vicksburg. Although hotly pursued by Richmond and other ships, the ram escaped to shelter under the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg. Farragut’s fleet again raced past Vicksburg and Richmond continued to provide escort for supply steamers and shore bombardment support.

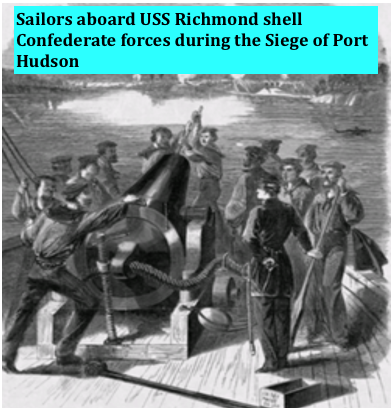

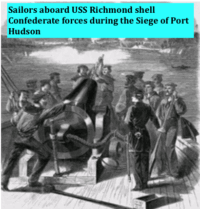

In one of the fiercest engagements of the war, Farragut’s squadron attempted to pass the Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson some 15 miles upriver from Baton Rouge on 14 March 1863. Only Hartford and Albatross succeeded in running the gauntlet, the remainder of the fleet having to turn back. Richmond, lashed alongside Genesee, found she could make no headway against the strong current as she came under fire from the shore batteries. Her executive officer, Comdr. Andrew B. Cummings, was mortally wounded. Richmond was struck soon afterward by a 42-pounder shell which ruptured her steam lines, filling the engine room and berth deck with live steam. As Genessee [sic; Genesee] was unable to tow Richmond against the current, the two ships reversed course, passing again through heavy shore fire. Attempts by General Banks’ Union Army troops to take Port Hudson on 27 May were no more successful and Federal forces afloat and ashore settled down for a long siege. Richmond continued to perform exacting duties, occasionally providing guns and their crews for use ashore.

Meanwhile strenuous efforts to take Vicksburg finally forced that city to surrender to General Grant on 4 July 1863. Five days later, the Richmond and other ships below Port Hudson helped Union ground forces to take possession of that last Confederate bastion on the Mississippi.

Richmond departed New Orleans on 30 July 1863 for a much-needed overhaul at New York Navy Yard.

On 12 October 1863, she sailed south, calling at Port Royal, S.C., and Key West, Fla., before rejoining Admiral Farragut’s squadron at New Orleans on 1 November; a fortnight later she began blockade duty off Mobile, Ala.

Richmond was present with Farragut’s fleet when the epic naval assault against Mobile Bay was mounted on 5 August 1864. For this attack, Richmond was lashed to the starboard side of Port Royal, and proceeded with the fleet across the bar. Fort Morgan opened fire and the action was soon general. Fifteen minutes later as the monitors were preparing to meet the defending Confederate casemate ram Tennessee, the Tecumseh struck a moored “torpedo” or mine and sank in seconds. Then Brooklyn, just ahead of Richmond, backed athwart Richmond’s bow in order to clear “a row of suspicious looking buoys.” Richmond and Port Royal in turn went hard astern, causing the entire line of wooden ships to fall into disarray. Admiral Farragut in Hartford decided the boldest course through the torpedo fields was the only one possible and gave his famous command “Damn the torpedoes … full speed ahead!” Moving into the bay, Richmond opened fire on the Confederate steamers Selma, Morgan, Gaines, and Tennessee. At the same time the gunboat Metacomet, cast off from Hartford, captured the Selma. Soon afterward Port Royal was sent after the disabled Gaines.

Tennessee attempted in vain to ram Brooklyn. Capable of only a very small speed, the southern ram was subjected to heavy fire from Hartford and Richmond. Tennessee passed astern toward Fort Morgan as Farragut’s fleet proceeded into the bay away from the fort’s fire. Tennessee’s commander, Franklin Buchanan, chose to follow and engaged the entire Union squadron.

Farragut attacked her with his strongest ships. Richmond proceeded in line abreast with Hartford and Brooklyn. For over an hour the Confederate ship was battered and even rammed by Hartford. By midmorning, Buchanan could see that his ship was a floating hulk and was surrounded by much stronger forces. Accordingly, a white flag was raised and the twin-turret monitor Chickasaw went alongside. Richmond suffered no casualties in the action and only slight damage.

Fort Morgan still put up determined resistance, however, and Richmond joined the squadron in a steady day and night bombardment. Invested by Union troops ashore, the fort finally capitulated on 23 August.

Richmond continued to operate in Mobile Bay and also in Pensacola Bay for a time before arriving at the Southeast Pass of the Mississippi River on 23 April 1865. That same evening, the Confederate ram Webb dashed down river from the Red River in an attempt to reach the open sea. Successfully passing Union ships at the mouth of the Red River and at New Orleans, Webb ran out of luck some 25 miles below New Orleans. Closely pursued by Union gunboats behind her, Webb found Richmond guarding the estuary leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Trapped, Webb was run ashore, set afire, and blown up by her crew.

| USS Richmond | |

| History | |

| United States | |

| Name | USS Richmond |

| Namesake | Richmond, Virginia |

| Builder | Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, Virginia |

| Launched | 26 January 1860 |

| Commissioned | 1860 |

| Stricken | June 1919 |

| Fate | Sold, 23 July 1919 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 2,604 tons |

| Length | 225 ft (69 m) |

| Beam | 42.6 ft (13.0 m) |

| Draft | 17.45 ft (5.32 m) |

| Propulsion | Steam |

| Speed | 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph) |

| Complement | 259 officers and enlisted |

| Armament | ·1 × 80-pounder Dahlgren smooth bore gun

·20 × 9 in (230 mm) Dahlgren smooth bore guns ·1 × 30-pounder Parrott rifle |

USS Richmond was a wooden steam-powered sloop-of-war in the United States Navy during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Service in the Caribbean

Richmond was launched on 26 January 1860 at Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia. Commanded by Captain D. N. Ingraham, the ship left Virginia on 13 October 1860, bound for the Mediterranean. Upon her return to New York City on 3 July 1861, the nation had been plunged into civil war, so the ship was immediately readied for sea. Her first war service began 31 July 1861 when she sailed for Kingston, Jamaica, to search for the elusive Confederate raider Sumter commanded by Raphael Semmes. Leaving Trinidad on 5 September, Richmond cruised along the southern coast of Cuba and around Cape San Antonio. Semmes reached New Orleans, Louisiana; and by 22 August, Richmond was at Kingston taking on coal again. Departing 25 August, Richmond arrived at Key West on 2 September, then proceeded north to join the Gulf Blockading Squadron.

Mississippi River blockade

After cruising before Fort Pickens, Richmond was ordered to the Head of the Passes at the mouth of the Mississippi River where she patrolled the river’s mouth to maintain the Union blockade. Richmond’s captain became commander of a small flotilla, which included the sloop of war, USS Preble, and the despatch vessel, USS Water Witch. The ships were taken across the bar at the Head of the Passes during the first week of October.

In the early morning darkness of the 12th, the Confederate ram Manassas and three armed steamers of Commodore Hollins’s Mosquito Fleet attacked Richmond and her consorts in an attempt to break the blockade in what became the Battle of the Head of Passes. Steaming under cover of darkness, the Confederate ships took the Union squadron by surprise. Richmond was taking on coal from the schooner, Joseph N. Toone, when Manassas rammed Richmond tearing a hole in the sloop’s side. Passing aft, the ram tried but failed to hit Richmond again before disappearing astern. Richmond‘s gunners got away one complete broadside from the port battery though, somewhat evening the score.

While USS Vincennes and Preble retired down the southwest Pass, Richmond covered their retreat. Three Confederate fire rafts were then sighted floating down river, and several large steamers were seen astern of them. In attempting to cross the bar, both Vincennes and Richmond grounded and were taken under fire by Confederate gunners afloat and ashore. Fortunately, the Army transport, McClellan, arrived with long range rifled guns on loan from Fort Pickens; and halted the second Confederate attack.

Richmond then cruised off the mouth of the river, blockading Confederate forces and aiding Army engineers erecting batteries on the banks of the South and Southwest passages. In mid-November 1861, she returned to Pensacola Bay for temporary repairs. On 22 November Richmond joined the steam sloop of war Niagara and the guns of Fort Pickens to bombard Pensacola Navy Yard, the Confederate defenses at Fort McRee, and the town of Warrington. On the second day of firing Richmond had one man killed and seven wounded when hit twice by shore fire. One shell hit forward, destroying railing and hammock nettings, and one aft on the starboard side glanced under her counter, exploding four feet (1.2 m) underwater, damaging her bottom and causing serious leaks. Richmond retired to Key West, Florida, and stood out from that port 27 November 1861 for repairs at the New York Navy Yard.

Capture of New Orleans

Richmond departed New York on 13 February 1862. Richmond joined the West Gulf Blockading Squadron off Ship Island on 5 March as Flag Officer David Farragut prepared to seize New Orleans, Louisiana. Richmond crossed the bar on 24 March with the fleet and began making preparations for battle. On 16 April, Farragut’s fleet moved to a position below Forts Jackson and St. Philip. Mounting over 100 guns, these forts were the principal shore defenses of New Orleans. The Confederates had also gathered a flotilla of requisitioned gunboats and were trying to complete the powerful casemate ram Louisiana as well. They further counted on using fire ships to disrupt the large Union squadron.

Hidden by intervening woods, the Union mortar flotilla under Commander David D. Porter began a six-day bombardment of the Confederate forts on 18 April 1862. The Confederates began sending fire rafts downstream, and Richmond reported dodging one in the early morning of 21 April which “passed between us and the Hartford, the great flames shooting as high as the masts.” On 24 April Farragut’s fleet ran past the forts, engaged and defeated the Confederate flotilla, and continued upriver for about 12 miles (19 km). Though Richmond was hit 17 times above the waterline, her chain armor kept out many rounds and limited her casualties to two killed and three wounded. Richmond landed her Marine detachment at New Orleans to help keep order until General Benjamin Franklin Butler‘s Army troops arrived. Richmond helped take possession of military installations at Baton Rouge, Louisiana on 10 May 1862. Four days later she cruised upriver, first to a point 12 miles below the juncture of the Red River, thence off Natchez River and finally to a position below the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg on 18 June 1862.

Vicksburg and Port Hudson

Farragut’s squadron, with Richmond in company, successfully passed Vicksburg exchanging heavy fire on 28 June 1862 and was present when Farragut’s fleet joined with Commodore Charles H. Davis‘ Western Flotilla above Vicksburg on 1 July 1862. Richmond again suffered two killed and was damaged almost as severely as during the New Orleans campaign. On 15 July 1862 the Confederate casemate ram Arkansas came out of the Yazoo River and ran past the Union Fleet above Vicksburg. Although hotly pursued by Richmond and other ships, the ram escaped to shelter under the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg. Farragut’s fleet again raced past Vicksburg and Richmond continued to provide escort for supply steamers and shore bombardment support.

In one of the fiercest engagements of the war, Farragut’s squadron attempted to pass the Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson some 15 miles (24 km) upriver from Baton Rouge on 14 March 1863. Only USS Hartford and USS Albatross succeeded in running the gauntlet, the remainder of the fleet having to turn back. Richmond, lashed alongside USS Genesee, found she could make no headway against the strong current as she came under fire from the shore batteries. Her executive officer, Comdr. Andrew B. Cummings, was mortally wounded. Richmond was struck soon afterward by a 42-pounder shell which ruptured her steam lines, filling the engine room and berth deck with live steam. As Genesee was unable to tow Richmond against the current, the two ships reversed course, passing again through heavy shore fire. Attempts by General Nathaniel P. Banks‘ Union Army troops to take Port Hudson on 27 May were no more successful and Federal forces afloat and ashore settled down for a long siege. Richmond continued to perform exacting duties, occasionally providing guns and their crews for use ashore.

Meanwhile, strenuous efforts to take Vicksburg finally forced that city to surrender to General Grant on 4 July 1863. Five days later, Richmond and other ships below Port Hudson helped Union ground forces to take possession of that last Confederate bastion on the Mississippi.

Mobile Bay

Richmond departed New Orleans on 30 July 1863 for a much-needed overhaul at New York Navy Yard. On 12 October 1863, she sailed south, calling at Port Royal, South Carolina, and Key West, Florida, before rejoining Admiral Farragut’s squadron at New Orleans on 1 November; a fortnight later she began blockade duty off Mobile, Alabama.

Pursuing blockade runners in 1864

Richmond was present with Farragut’s fleet when the epic naval assault against Mobile Bay was mounted on 5 August 1864. For this attack, Richmond was lashed to the starboard side of USS Port Royal, and proceeded with the fleet across the bar. Fort Morgan opened fire and the action was soon general. Fifteen minutes later as the monitors were preparing to meet the defending Confederate casemate ram Tennessee, USS Tecumseh struck a moored “torpedo” or mine and sank in seconds. Then USS Brooklyn, just ahead of Richmond, backed athwart Richmond’s bow in order to clear “a row of suspicious looking buoys.” Richmond and Port Royal in turn went hard astern, causing the entire line of wooden ships to fall into disarray. Admiral Farragut in Hartford decided the boldest course through the torpedo fields was the only one possible and gave his famous command “Damn the torpedoes … full speed ahead!” Moving into the bay, Richmond opened fire on the Confederate steamers Selma, Morgan, Gaines, and Tennessee. At the same time the gunboat USS Metacomet, cast off from Hartford, captured Selma. Soon afterward Port Royal was sent after the disabled Gaines.

Tennessee attempted in vain to ram Brooklyn. Capable of only a very small speed, the southern ram was subjected to heavy fire from Hartford and Richmond. Tennessee passed astern toward Fort Morgan as Farragut’s fleet proceeded into the bay away from the fort’s fire. Tennessee‘s commander, Franklin Buchanan, chose to follow and engaged the entire Union squadron.

Farragut attacked her with his strongest ships. Richmond proceeded in line abreast with Hartford and Brooklyn. For over an hour the Confederate ship was battered and even rammed by Hartford. By mid morning, Buchanan could see that his ship was a floating hulk and was surrounded by much stronger forces. Accordingly, a white flag was raised and the twin-turret monitor USS Chickasaw went alongside. Richmond suffered no casualties in the action and only slight damage.

Fort Morgan still put up determined resistance, however, and Richmond joined the squadron in a steady day and night bombardment. Invested by Union troops ashore, the fort finally capitulated on 23 August.

Richmond continued to operate in Mobile Bay and also in Pensacola Bay for a time before arriving at the Southeast Pass of the Mississippi River on 23 April 1865. That same evening, the Confederate ram Webb dashed down river from the Red River in an attempt to reach the open sea. Successfully passing Union ships at the mouth of the Red River and at New Orleans, Webb ran out of luck some 25 miles (40 km) below New Orleans. Closely pursued by Union gunboats behind her, Webb found Richmond guarding the estuary leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Trapped, Webb was run ashore, set afire, and blown up by her crew.

A total of 33 sailors and marines earned the Medal of Honor while serving aboard Richmond during the Civil War, more than on any other ship.[3] The first medals went to four members of the ship’s engineering department for their efforts after an engine room was damaged by shellfire during the 14 March 1863 attack on Port Hudson. The remaining medals went to three marines and twenty-six sailors for their actions at the Battle of Mobile Bay.

Attack on Port Hudson, 14 March 1863

- Second Class Fireman John Hickman

- First Class Fireman Matthew McClelland

- First Class Fireman John Rush

- First Class Fireman Joseph E. Vantine

Battle of Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864

| · Yeoman Thomas E. Atkinson

· Quartermaster John Brazell · Captain of the Top Robert Brown · Master-at-Arms William M. Carr · Coxswain James B. Chandler · Quartermaster Thomas Cripps · Chief Quartermaster Cornelius Cronin · Boatswain’s Mate Charles Deakin |

· Chief Boatswain’s Mate William Densmore

· Coal Heaver William Doolen · Boatswain’s Mate Adam Duncan · Coxswain Hugh Hamilton · Coxswain Thomas Hayes · Captain of the Top John H. James · Captain of the Top William Jones |

· Sergeant James Martin, II (USMC)

· Captain of the Top James McIntosh · Sergeant Andrew Miller (USMC) · Captain of the Top James H. Morgan · Captain of the Forecastle George Parks · Seaman Hendrick Sharp · Coxswain Lebbeus Simkins |

· Captain of the Forecastle James Smith

· Second Captain of the Top John Smith · Coxswain Oloff Smith · Ordinary Seaman Walter B. Smith · Orderly Sergeant David Sprowle (USMC) · Coxswain Alexander H. Truett · Quartermaster William Wells |

Post-war service

Richmond departed New Orleans on 27 June, arrived at the Boston Navy Yard on 10 July, and was decommissioned there on the 14th. In 1866 she was fitted out with a new set of engines.

Recommissioned at Boston on 11 January 1869, Richmond departed on 22 January for European waters. Arriving at Lisbon on 10 February, she called at various Mediterranean ports during the remainder of the year and during 1870 was stationed at Villefranche and Marseille to protect U.S. citizens potentially endangered by the Franco-Prussian War. After the peace was made at Versailles, Richmond cruised the Mediterranean again. She returned to Philadelphia on 1 November 1871 and decommissioned there on the 8th.

Selected for service with the West Indies Squadron, Richmond was recommissioned on 18 November 1872 and stood out from Hampton Roads on 31 January 1873. Arriving at Key West 11 February, she surveyed shoals near Jupiter Inlet, then cruised in the West Indies. On 7 April she was at Santiago de Cuba to assist in securing the release of U.S. seamen held by the Spanish. She then called at Havana and Matanzas before returning to Key West at the end of the month.

Ordered to the Pacific in May, Richmond rounded Cape Horn and arrived at San Francisco on 28 November. After repairs, she departed California, 14 January 1874, as flagship of the South Pacific Station. Throughout 1874 and 1875 she cruised the west coast of Latin America. In September 1876 she again doubled Cape Horn and, after cruising off Uruguay and Brazil, reached Hampton Roads on 22 August 1877. On 18 September she was decommissioned for repairs at the Boston Navy Yard.

Recommissioned on 19 November 1878, Richmond’s next duty was as flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. Departing Norfolk 11 January 1879, Richmond passed into the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal, hoisting the flag of Rear Admiral Thomas H. Patterson at Yokohama on 4 July 1879. For four years Richmond cruised among the principal ports of China, Japan, and the Philippines, serving as flagship until 19 December 1883 when Trenton relieved her. While at Shanghai on 17 November 1879, Landsman Thomas Mitchell rescued a shipmate from drowning, for which he was later awarded the Medal of Honor. Receiving a new crew at Panama in September 1880, Richmond remained on station until departing Hong Kong for the United States on 9 April 1884. Again transiting the Suez Canal, Richmond reached New York on 22 August and was decommissioned for repairs.

Completely overhauled, Richmond was recommissioned at New York on 20 January 1887 for duty on the North Atlantic Station. Into 1888 she cruised from Halifax to Trinidad. On 27 June 1888 she was detached for foreign service.

Departing Norfolk on 2 January 1889, Richmond was assigned to the South Atlantic Station. Again serving as squadron flagship, she cruised off Uruguay and Brazil for over a year, returning to Hampton Roads on 28 June 1890. On 7 October, she arrived at Newport, Rhode Island, where she served as a training ship until 1893. The following year she steamed to Philadelphia; served there as a receiving ship until 1900; then remained moored at League Island until ordered to Norfolk in 1903. At Norfolk, she served as an auxiliary to the receiving ship USS Franklin until after the end of World War I.

Richmond was struck from the Navy list in June 1919 and sold to Joseph Hyman & Sons, Philadelphia, on 23 July. She was delivered to that firm on 6 August for breaking up. Beached at Eastport, Maine and burned to recover valuable metal sometime in the 1st half of 1920.

Frederick Gutekunst (September 25, 1831 – April 27, 1917) was an American photographer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He opened his first photographic portrait studio with his brother in 1854 and successfully ran his business for sixty years. He grew to national prominence during the American Civil War and expanded his business to include two studios and a large phototype printing operation. He is known as the “Dean of American Photographers” due to his high quality portraits of dignitaries and celebrities. He worked as the official photographer of the Pennsylvania Railroad and received national and international recognition for his photographs of the Gettysburg battlefield and an innovative 10-foot long panoramic photograph of the Centennial Exposition.

712 Arch St. Philadelphia, PA

Nestled between the modern-day Pennsylvania Department of Transportation and the Federal Reserve Bank lies a parking lot at 712 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA. Unbeknownst to most, the small acreage holds far more history than initially meets the eye. One hundred and fifty-five years prior, this space housed the studio of one of the most prolific and successful photographers of the American Civil War Era.

Frederick Gutekunst was born around 1831 to 1834 in Germany, like his father, who made a modest living as a carpenter. The pair traveled abroad and found themselves in Philadelphia in 1837 where they then remained. Gutekunst and his family lived in a block in Philadelphia where North American Street and Germantown Avenue meet. The neighborhood consisted of primarily German immigrants who could afford to live in the location. The younger Gutekunst spent the majority of these early years indentured to Prothonotary Joseph Simon Cohen at the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, as his father pushed for the boy to become a lawyer. However, disinterested in law, at the age of eighteen he began to cultivate a deep interest in the practice of daguerreotype, an early methodology for processing photography.

Between part-time jobs and frequently visiting notable photographer and writer, Marcus Aurelius Root’s galleries, Gutekunst started to further his own passion in the field. In time, he began to slowly gather parts for a camera of his own. After having acquired a lens and battery, his father helped build a frame to house Frederick’s collected parts, effectively jumpstarting his son’s career in photography.

Around this time, Frederick’s skill and expertise started to attract attention, some of which came from his brother Louis Gutekunst, who noticed his sibling’s talent and appetite for the medium. Working as a barber, Louis had a steady income and desired to help his younger brother with his goals. At some point, Frederick expressed interest in a storefront on Arch St. Understanding what this could mean for the aspiring photographer, in 1859 Louis rented the establishment, immediately. Frederick Gutekunst used this building throughout the entirety of his photography career. At this location, he hosted his collection of artworks, staged portraits, and met with those who wanted to buy from him.

Shortly thereafter, the nation found itself plunged into crisis as sides formed and brother fought brother. The American Civil War began in 1861 and altered the careers and lifestyles of the populace in a myriad of ways. As for Gutekunst, the effect was no different. In 1863, Philadelphia felt threatened by the destructive nature of the Gettysburg invasion and found itself perpetually closer to bitter conflict. Soldiers became much more prominent in the city as Philadelphia raised troops and tended to those in service. These soldiers soon found their way to Gutekunst studio to have their portraits made as it was the custom to have ones photo taken in military uniform, both as record and for relatives. Being talented in his work, word traveled about Gutekunst Studios on 712 Arch St., and soon enough, an array of military brass found its way to the now bustling studio.

Out of all of his work, the image that initially set Gutekunst apart from his contemporaries and brought about mass military brass interest was his portrait of Ulysses S. Grant. In an interview with The Photographic Times & American Photographer, Gutekunst stated, “I’m told the picture is the best taken of Grant; it is the model for the statue of him in Galena, and General Sherman sent me a letter in which he asserts his belief that it is the most characteristic of the great General.”

This success brought an immediate flow of income as well as a now seemingly endless supply of work. Gutekunst needed a larger space and workforce. The answer came in hiring his brother Louis to develop prints and meet with business partners, Gutekunst also hired several new staff members to take care of miscellaneous tasks as he purchased the remaining rooms in his now bustling studio. Gutekunst now occupied the entirety of the building and decorated it with all manners of apparel to delight customers and heighten the grandeur of his artwork. Located in the reception room, a large cylinder that looked similar to a music box filled the room with music to entertain and occupy eager customers.

As war gradually came to an end and a scarred nation began to heal itself, Gutekunst continued to thrive in his domain. He went on to photograph the Pennsylvania Railroads in 1870. He captured a gorgeous panorama view of the 1876 Centennial Exposition, a feat that was incredibly difficult to accomplish. Gutekunst also photographed many famed historic figures, such as: Lucretius Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Caroline Still Anderson, Abraham Lincoln, and Grover Cleveland, to name a few. Copies of Gutekunst’s work often found residence in his studio for visitors and patrons to view.

Success led to upscaling in the studio and the need for an additional branch with trusted friend and advisor William Braucher as manager. Over time Gutekunst incorporated his business and gave stock to the older employees as compensation for their efforts. Frederick Gutekunst continued to work until his death in 1917, but not before becoming declared the Dean of American Photographers by the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph and one of the most accomplished men in the field during the era. While the Gutekunst Studios may no longer be standing, the artwork and story of the immigrant family who found incredible success and furthered the field of photography continues to inspire those inside and outside the field today.

The growing demand for pictures during and after the Civil War led him to add the upper floors of No. 704 Arch Street to his studio at 706.