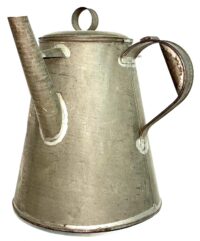

Civil War Period Tinned Side Spout Coffee Pot

$110

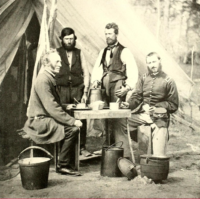

Civil War Period Tinned Side Spout Coffee Pot – This is a fine example of a Civil War period, tinned, sheet iron, side spout coffee pot, a standard element present in all Civil War northern and southern camps. All of the seams of the pot, per the manufacturing capabilities of the mid-19th century which precluded most tin-crimping modes, exhibit lead soldered joinery; per construction modes of that era, as well, is the flat bottom of the pot. Little of the original tinning remains on the exterior of the pot, although most remains on the interior, which does show some minor areas of rust spotting, although no holes are present. The pot remains in overall excellent condition.

Measurements: H – 10.25”; Diameter of the base – 8.5”

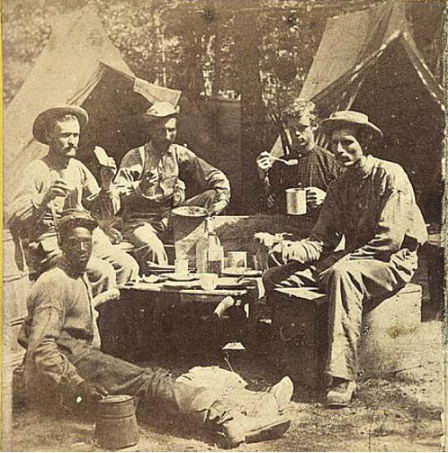

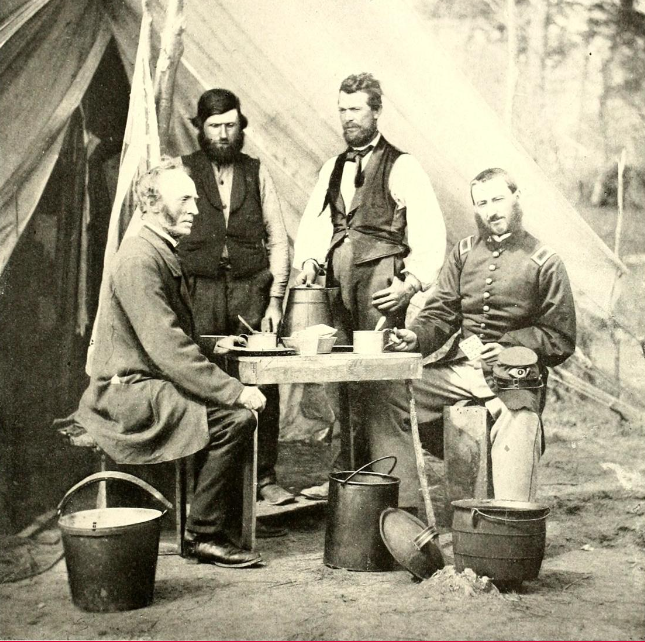

Coffee and the Civil War Soldier

By Ashley Webb, Historical Society of Western Virginia

Coffee, a staple before the Civil War in most households, became a luxury, and a beverage soldiers craved. It was what bolstered and also refueled them, increasing morale, providing comfort before a battle, and giving soldiers the fortitude to continue a march. One Civil War historian noted that the word coffee was used more often in Civil War soldiers’ diaries and letters home than words like ‘war,’ ‘slavery,’ or ‘Lincoln.’ Union soldiers remarked on how often they made coffee, and Confederate soldiers commented on the lack of coffee, discussing and inventing recipes with odd substitutions in order to simulate the taste. Insipid substitutions included whatever could be found and roasted in the field, including chicory, acorns, dandelions, rye, peanuts, and peas. Recipes or unique blends were sent from home. General George Pickett received one concoction from his wife, and enthusiastically thanked her: “No Mocha or Java ever tasted half so good as this rye-sweet-potato blend!”

Trade continued throughout the North, with the allotted rations including 36 pounds of coffee a year for every Union soldier. The over-abundance of coffee in the North and the lack of coffee in the South grew into a point of comradery between soldiers, and the task of brewing coffee one that they looked forward to. It was a “soldier’s chiefest bodily consolation,” and one soldier, with some surprise, that he was still alive, wrote home that “what keeps me alive must be the coffee.” As the war continued, coffee distribution to Confederates, to both citizens and soldiers alike, became nonexistent. One Confederate soldier who had received steady rations up until the summer of 1863 remarked that “our shortness of rations began, and continued rather to intensify until the end. For one period of about two months, it consisted of only one small loaf of baker’s bread and a gill of sorghum syrup daily.” Another wrote “We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee. And nobody can soldier without coffee.”

In the South, the scarcity of coffee made the acquisition of it all the more precious. In an oral history from one Virginia family, as Union soldiers moved out after a small skirmish in the Northern Neck, Confederates scoured the campsites for every bean left behind, regardless of the dirt and debris clinging to the dropped bits. It was too precious of a commodity to leave in the field. In other cases, informal truces arose, with soldiers on both sides creating imaginative ways to acquire what they wanted without causing too much disruption. In another tale of folklore, Confederate soldiers sent small crafted sailboats to Union soldiers across the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, Virginia, requesting coffee be returned as soon as the wind changed in exchange for tobacco. In another instance, a Confederate soldier slipped a note across enemy lines, stating “I send you some tobacco and expect some coffee in return…yours Rebel.”

In two different diaries, soldiers mentioned physical truces with the opposing side. In Petersburg, Virginia, James Hall, a soldier in the 31st Virginia Infantry, mentioned that his troop and a Union unit maintained a truce “for a few minutes,” while he “exchanged papers with a Yankee,” and others received coffee before “both parties resumed firing.” Charles Lynch, a soldier in the 18th Connecticut Infantry, describes a similar situation: “Our boys and the Johnnies on the skirmish line entered into an agreement not to fire on one another. For proof they fixed bayonets on their guns, sticking them in the ground, butts up….Boys would meet between the lines, exchange tobacco for coffee. The rebs were always very anxious to get hold of New York papers.”

Yet, while Confederates were happy with whatever poor tasting brew they could get, even if it contained no physical coffee, some Union soldiers found the taste of their abundant coffee rations to be less than desirable. F.Y. Hedley of the 32nd Illinois commented that coffee in his camp was “strong enough to float an iron wedge,” while another bluntly stated that ‘the coffee we get here [in Camp Misery] is poor stuf [sic].” Others were grateful even if it was a bad cup of joe. Charles Nott, a 16-year-old Union soldier described his coffee one evening at dinner as something “you probably wouldn’t recognize in New York. Boiled in an open kettle, and about the color of a brownstone front, it was nevertheless … the only warm thing we had.” William Reid, a soldier in the Wisconsin 39th Infantry, relied on coffee during the long march from Centralia to Cairo, Illinois, to keep him going, and much like Charles Nott, wrote in his diary, “we were each furnished with a cup full of coffee which although it was not very good yet we drank it and were glad of it.”

On both sides of the war, coffee was an important part of a soldier’s daily life. Even when it couldn’t be found, soldiers created unique substitutes that resembled coffee in order to get through the tasks at hand. While coffee certainly didn’t win the war, it played a larger role in the social and economic aspects of the period, influencing generations for years to come.