Large Format Albumen from Glass Plate Negative by Andrew J. Russell of Confederate Fort Mahone (“Fort Damnation”) – April, 1865

$650

Large Format Albumen from Glass Plate Negative by Andrew J. Russell of Confederate Fort Mahone (“Fort Damnation”) – April, 1865 – This large albumen of Ft. Mahone or Confederate Battery #29 is attributed to noted artist and photographer, Captain Andrew J. Russell, Co. F 141st NY Infantry, taken after the fall of Petersburg, in April of 1865. The image depicts several Union soldiers and officers, including Russell who is seated, seventh from the left, with his arms folded, seated, looking right. Numerous other images, also attributed to Russell, seemingly taken on the same day, show several Confederate fortifications. This rare albumen was printed from a glass plate negative, now housed in the Library of Congress. The albumen is mounted on original, period card stock with an early, crudely inked label that reads: “Rebel Entrenchments”; written in period pencil, on the back of the image is: “Rebel Entrenchments”. Additional Russell images, taken on the same day that this image was taken, identify another officer, also in this image: Capt. John B. Kopp, 2nd Pa. Heavy Artillery. This a rarely encountered albumen taken by one of the foremost artist and photographers of the 19th century. It remains in very good condition, exhibiting some minor foxing on the card stock.

Andrew J. Russell

| Residence was not listed;

Enlisted on 8/19/1862 at Elmira, NY as a Captain.

On 9/11/1862 he was commissioned into “F” Co. NY 141st Infantry He was discharged on 9/9/1865 |

141st NY Infantry

( 3-years )

| Organized: Elmira, NY on 9/11/62 Mustered Out: 6/8/65 at Washington, DCOfficers Killed or Mortally Wounded: 4 Officers Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 2 Enlisted Men Killed or Mortally Wounded: 71 Enlisted Men Died of Disease, Accidents, etc.: 172 (Source: Fox, Regimental Losses) |

| From | To | Brigade | Division | Corps | Army | Comment |

| Sep ’62 | Oct ’62 | Unattached | Defenses of Baltimore | Middle Department | ||

| Oct ’62 | Feb ’63 | 2 | Abercrombie’s | Military District of Washington | ||

| Feb ’63 | Apr ’63 | 2 | Abercrombie’s | 22 | Department of Washington, D.C. | |

| Apr ’63 | May ’63 | Porter’s | Gurney’s | 7 | Department of Virginia | |

| May ’63 | Jul ’63 | 2 | 2 | 4 | Department of Virginia | |

| Jul ’63 | Sep ’63 | 2 | 3 | 11 | Army of Potomac | |

| Sep ’63 | Apr ’64 | 2 | 3 | 11 | Dept and Army of Ohio and Cumberland | |

| Apr ’64 | Jun ’65 | 1 | 1 | 20 | Dept and Army of Ohio and Cumberland | Mustered Out |

NEW YORK

ONE HUNDRED AND FORTY-FIRST INFANTRY

(Three Years)

|

One Hundred and Forty-first Infantry.-Cols., Samuel G. Hathaway, John W. Dininy, William K. Logie, Andrew J. McNett; Lieut.-Cols., James C. Beecher, William K. Logie, Edward L. Patrick, Andrew J. McNett, Charles W. Clanharty; Majs., John W. Dininy, Edw. L. Patrick, Chas. W. Clanharty, Elisha G. Baldwin.

This regiment, recruited in the counties of Chemung, Schuyler and Steuben-the 27th senatorial district-was organized at Elmira, and there mustered into the U. S. service for three years on Sept. 11, 1862. The regiment left for Washington on the 15th, and in April 1863, was ordered to Suffolk, Va., in the 3d (Potter’s) brigade, Gurney’s division, Department of Virginia.

In June and July, following, it was engaged with slight loss at Diascund bridge, and Crump’s cross-roads. In July, 1863, it joined the 2nd brigade (Krzyzanowski’s), 3d division (Schurz’s), 11th corps, with which command it went to Tennessee in September and joined Grant’s army at Chattanooga.

In October it went to the support of the 12th corps at Wauhatchie, sustaining a few casualties, and the following month was present at the battle of Missionary ridge. When the 11th and 12th corps were consolidated in April, 1864, to form the 20th, the 141st was assigned to the 1st (Knipe’s) brigade, 1st (Williams’) division of the new corps.

It moved on the Atlanta campaign early in May and bore a conspicuous part in all the important battles which followed, including Resaca, Dallas, Acworth, Kennesaw mountain, Peachtree creek and the siege of Atlanta. The regiment was heavily engaged at the battle of Resaca, where it lost 15 killed and 77 wounded; at Kennesaw mountain, including the engagement at Golgotha, Nose’s creek and Kolb’s farm, it lost 12 in killed, wounded and missing; and at Peachtree creek, it experienced the hardest fighting of the campaign, being under a severe front and flank fire for nearly 4 hours, and repulsing three charges of the enemy.

The casualties here were 15 killed and 65 wounded. Among those killed was the gallant young Col. Logie, and among the severely wounded were Lieut.-Col. McNett and Maj. Clanharty. The regiment started on the campaign with 22 officers and 434 enlisted men. Its casualties in battle up to Sept. 1 amounted to 210. It remained at Atlanta until Nov. 15, when it started with Sherman on the march to the sea.

It took part in the siege of Savannah and the following year closed its active service with the campaign through the Carolinas, losing a few men in the battle of Averasboro, N. C. After Johnston’s surrender it marched on to Washington, took part in the grand review, and was there mustered out on June 8, 1865, under Col. McNett. It lost by death from wounds 4 officers and 71 men; by disease and other causes, 2 officers and 172 men-total, 249. |

Andrew J. Russell

Nineteenth-century American Civil War and Union Pacific Railroad photographer Andrew J. Russell was born in Walpole, New Hampshire, on March 20, 1829, and raised in New York State. After earning several commissions as a portrait and landscape painter, he helped form a local militia at the outset of the Civil War. He learned photography after joining the Army and, in the spring of 1863, was made the Army’s first official photographer under General Herman Haupt. Following the War he was hired by the Union Pacific Railroad to photographically document the construction and completion of the eastern portion of the American transcontinental railroad.

Russell died in Brooklyn, New York, in September 1902.

A.J. Russell – courtesy of the Getty Museum

Andrew Joseph Russell, a captain in the volunteer infantry, became a photographer during the American Civil War. As photographer-engineer for the United States Military Railroad Construction Corps, he was assigned to photograph battlefields and campsites in Virginia. He also photographed engineering projects and contributed images to what was probably the world’s first technical manual illustrated with photographs.

The Union Pacific Railroad Company later hired Russell to document the building of the transcontinental railroad, creating a visual document “calculated to interest all classes of people, and to excite the admiration of all reflecting minds as the colossal grandeur of the Agricultural, Mineral, and Commercial resources of the West are brought to view.” For about two years following the celebrated driving of the last spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869, he continued to photograph the areas around the railroad and began to write dispatches about the West for Eastern newspapers. After he returned to New York, he maintained a photography studio there and never traveled West again.

Russell’s Civil War Photographs (Dover Photography Collections)

by Captain A. J. Russell (Author)

Captain A. J. Russell did not photograph celebrities, run fashionable photo galleries, or publish collections of his “views”; most histories of American photography can barely stretch his biographical data into a paragraph. His peers and superiors recognized the quality of his works, but as with other unassuming photographs of the Civil War, many of his pictures were later attributed to Brady. Yet he is unquestionably a major figure in 10th-century American photography, a pioneer in every sense: he was one of the only two or three official Civil War photographers, perhaps the only one who was also a soldier; after the war he headed west to become the official photographer of the Union Pacific Railroad as it breached the frontier.

Russell’s frontier photographs came to be better known than those he took as engineer-photographer with the elite Railroad Construction Corps, attached to General Grant’s Military Railroad. These early experiences in military photography, however, aside from their contribution to photo-technological development, prove Russell a remarkable camera artist. Here, reproduced from one of the few surviving scrapbooks of his photographs, are 116 rare prints, many never before published, restoring a largely forgotten artist to an audience ready to appreciate him.

Russell’s duty included recording the activities of the crucial Railroad Corps as it helped move the Union Army through Virginia. At the same time, he witnessed and chronicled the campaigns of Fredericksburg, Petersburg, Brandy, and Alexandria, and was there to photograph Richmond in ruins. He documents not only tracks, bridges, depots, and engines of war, but surrounding scenes: Bull Run, Meade’s headquarters at Culpepper and Brandy, burying the dead after the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, Lee’s residence at Arlington, “Fort Hell” and “Fort Damnation,” Libby Prison in Richmond, the Smithsonian Institution, the Capitol, and a heretofore unseen photograph of Lincoln’s funeral car.

The full-page panoramas capture the wastage of war that so shocked the civilian public when first exposed to photographs of battles. There are also “aesthetic” shots, landscapes such as that as Great Falls on the Potomac, which offer relief. New captions and a Preface fill in historical, biographical, bibliographical, and photographic detail. This collection of views by a professional military photographer, perhaps the very first in his profession, is an archive of engineering triumphs and human loss; students of the Civil War will discover views unseen in the standard works, while lovers of photography will rediscover in Russell an early master of the art.

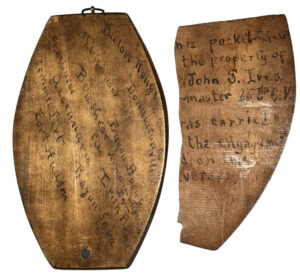

| Nunda

Historical Society |

Nunda

Livingston Co New York |

| Andrew Russel’s father Joseph Russell settled in Oakland in 1825 and moved to Nunda in 1838. Russell,

born in 1829, was listed as one of Nunda’s “painting artists” by 1851 when, at age 22, he was teaching penmanship at the Nunda Literary Institute until it burned in 1859. By the late 1850s Russell had also taken up photography and this photo may have been taken in his studio, possibly a Select School on Church Street. His reputation as an artist had already earned him several important commissions for paintings and by the middle of 1860 he had opened a studio in New York City. |

| During the Civil War, in August 1862, Russell enlisted in the 141st New York Volunteers and was an

official Army photographer, the only soldier-artist known to have served in the Civil War. Captain Russell started in Washington but in 1863 was assigned to General Herman Haupt’s U.S. Military Railroad Construction Corps. active in the crucial Virginia sector of the war facilitating the movements of the Armies of the Rappahannock, of Virginia, and of the Potomac. |

Russell documented bridge building activities, railroad construction techniques, camps and supplies of

the Corps. He also photographed troops, battlefields and combat aftermath scenes. His work provided

some of the most coherent documentation of the war. He photographed at Marye’s Heights during the

battle of Fredricksburg, at Petersburg, Alexandria, and the fall of Richmond.

Russell’s large camera, bottles of chemicals and “window-pane” glass were transported in a crude

horse-drawn darkroom. In spite of the conditions in which Russell worked, the quality of his

photographs is remarkable. The artistic quality and usefulness of his work were both highly valued by

the government in Washington and his images were published in special albums and given to visiting

dignitaries. One of these albums has long been in the Virginia Historical Society Collection in Richmond.

Unfortunately, Russell’s renown as a Civil War photographer was later forgotten and many of his best

images were attributed to Matthew Brady or Brady’s associates. When two more albums of Russell’s

images surfaced in 1978 and 1980, Civil War photo-historians were able to correctly identify these

images as Russell’s work. They also discovered the existence of images that had never been seen

before, such as President Lincoln’s Funeral Car.

Andrew J. Russell’s “United States Military Rail Road Photographic Album,” a magnificent album with

107 albumen prints depicting the railroads, battlefields and landscapes of the Civil War sold at auction

in 2011 for for $156,000.

| After the War, Russell was hired by the Union Pacific as their Official Photographer to document the

building of the transcontinental railroad during the years 1868-1869. In this position he made over 200 10” x 13” wet plate negatives along the route and, with four assistants, made more than 400 stereographic negatives. One hundred years later, in 1969, all of Russell’s negatives were discovered in the archives of the American Geographical Society in New York. They had been mistakenly attributed to Stephen J. Sedgwick, a nineteenth century lecturer who had gained considerable prominence with his “illuminated lectures” on world religions, natural history and the Pacific Railroad. As he traveled west, Russell photographed Native Americans, pioneer settlers, and scenic views along the route. All of Russell’s glass negative are now at the Oakland Museum of CA (OM:CA). A recent exhibit “Pushing West: The Photography of Andrew J. Russell” may be viewed using this link. The entire Andrew J. Russell Collection may be viewed here. Russell made three trips along the route, one in 1868 and two in 1869. He used an outdoor camera of his own design, which he described in “Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin” in 1870 as “…compact, durable, light, and convenient, and is far from being complicated in its construction…” He also used a stereoscopic-view camera, producing double image negatives. Russell published over 400 of these images when he returned to his New York studio in 1870 and they were published again later by promoter/entrepreneur Sedgwick who touted them as his own. In May1869 Russell took one of the most famous images in American history, “East and West Shaking Hands at Laying of Last Rail” upon completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. What Russell had compiled was a visual and historical record of this great achievement, resulting in an important contribution to both American photography and American history. A photograph of this Ceremony with Flag and Camera sold at auction in 2010 for $36,000.

|